Summary

British Officer and Prisoner of War, John R. Pennycook, recounts his capture, transfer and escape from the camp in Chieti, Italy, in 1942-1943. Along with 14 other men, Pennycook escaped via a tunnel when German soldiers took over the camp on the 21st September 1943. These accounts follow Pennycook and Gordon McFall on their journey to Allied occupied territory. They are arranged in order of events and have been split into sections by Pennycook.

Please contact the Trsut to see Pennycook’s original archive file for newspaper clippings from 1944 in the ‘Crusader’, which detail Hugh Gordon Brown’s account of the tunnel at Chieti and their escape.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

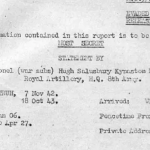

[Digital page 1]

[Handwritten note in Keith Killby’s writing:] from 1944 and ‘Crusader’ with Hugh Gordon Brown’s account of tunnel at Chieti and their get away. H.G.B. had already been killed in air crash.]

[Title:] JOHN R. PENNYCOOK M.B.E. (Mily).

[Subtitle:] P.O.W. ITALY 1942 -1943.

[Subtitle:] ESCAPE FROM CAMPO CONCENTRAMENTO PRIGIONIERE DEL GUERRA. CHIETI, ITALY and other incidents.

[Handwritten note:] Duplicate

[Digital page 2, original page 000001]

[Subtitle] ON THE SUBJECT OF ESCAPING

It is every officer’s duty to try to escape so this became my main occupation, certainly after Christmas 1942 until our successful bid in 1943.

Fifteen hundred officers inhabited the camp, so it was not possible to involve everyone in any attempt.

An Escape Committee was formed, consisting of about six officers appointed by the SBO (Senior British Officer) who was a Lieut. Col. [Lieutenant Colonel] from, if I remember correctly, the Mahrattas of the 4th Indian Division. The names of the members of the Committee I never knew. It was essential, so far as possible, that they should be kept secret, so only a few were aware of some of them. I believe there was one contact known in each area of the sleeping quarters. Every suggestion or plan for escape had to be vetted by the Committee before any attempt was made. The same applied to any long term plans, such as the digging of a tunnel. This was to ensure that:

a. Any plan would have a reasonable chance of success.

b. No new plan would be put into operation in the close vicinity of an existing one, since this could jeopardise the success of the earlier approved one.

The Committee also controlled any escape aids which had been acquired. These might include compasses, maps, knives etc. Some of these may have arrived hidden in parcels from home. They also controlled supplies of suitable food which could be carried by the escapee, often in the form of concentrated rations which may also have been concealed in parcels from home.

Only when the Escape Committee approved a plan could preparations be made for it to become operational. Other sections of the camp could become part of the general escape plans. For example, the gardening squads were involved in the distribution of earth brought out from the various tunnels. The soil was brought out by the tunnellers, often concealed in sacks suspended by string from their necks, two bags hanging underneath each trouser leg. The bags were released in the area where the gardeners worked and they would rake it into recently dug earth to camouflage the fresh soil. It was amazing how many areas were repeatedly dug over without anything ever being planted in them!

Another good example of how invaluable help could be obtained from the other departments was the Theatre Workshop where scenery etc. was constructed for the various shows being produced. The Italians had actually been persuaded to supply a certain amount of timber for this purpose and so it, along with broken up bed boards were made into props to hold up the earth in some of the tunnels. Other materials which had been supplied to make costumes etc. were sometimes used to make civilian suits, hats, suitcases and so forth. Sometimes suitable uniforms were adapted to German or Italian uniforms, although this was a risky disguise and would most certainly end in the death of the wearer if discovered. I expect that, more often than not, this disguise would be refused permission by the Committee.

The Drama groups and the orchestras also played their part by organising noisy diversions when some escape action was taking place. By creating a rammy [noisy disturbance] in one part of the camp this could divert the guards’ attention and allow work on the escape to proceed.

[Digital page 3, original page 000002]

I recall we tied a string from our window to a window opposite in the next building and about two o’clock in the morning we pulled a dummy across the space between the two buildings. This resulted in the sentries on the walls on opposite sides of the camp, a distance of perhaps 150/200 yards apart, shine their searchlights and aim their rifles in the general direction of each other. We never anticipated nor was there a fatality but it did create a diversion in that area away from where work towards escape was taking place.

Escape from Italy was not easy. We were guarded by many fourth rate Italian soldiers at a ratio of 4 to 1 and seldom out of their sight. These men had proved themselves to be brutal cowards when the war was going their way.

Of 602 attempted escapes reported by camps to the Italian War Ministry, only 6 resulted in a ‘home run’, four of which were to the Vatican. This was a ratio of one in a hundred tried and one in ten thousand succeeding. By September 1943 there were 72 main camps and 12 hospitals, and approximately 80,000 Allied prisoners held.

An Armistice was signed with Badoglio’s government on 8th September, 1943. One of the terms was that the Italian Military Authorities should immediately free all prisoners. As a result of the chaos which ensued this did not happen. S.B.O.’s [Senior British Officer] of every camp had received a secret message -“In the event of an Allied invasion of Italy, ensure that Prisoners of War remain within the camp. Authority is granted to all Officers Commanding to take necessary disciplinary action to prevent individual Prisoners of War attempting to re-join their own units.” Churchill himself was unaware of this order and gave Alexander an order to rescue all Prisoners of War at any cost, assuming that they would seize the chance of freedom. Almost all S.B.O.’s had received the initial order which had been sent from M.I.9 [Military Intelligence section 9] on Montgomery’s instructions and most obeyed. Accordingly, in our camp P.G.21 in Chieti, the S.B.O., a British Lieut. Col. of the Indian Army, not only ordered no-escapes to be made but put British Officers in the guard boxes on top of the wall to prevent anyone going over the top. This resulted in him being the subject of a post war enquiry instigated by indignant Prisoners of War who had been prevented from getting away. Since the offence was “failing to DISOBEY a legitimate and explicit order which had become inappropriate, he was cleared of all blame.

[Digital page 4, original page 000003]

[Subtitle]22 JUNE 1942

This was the day on which I was captured by the African Corps of the German Army in the Western Desert on the perimeter of the Tobruk defences.

I was a forward observation officer for C Troop 68th Medium Regiment, Royal Artillery, in support of the 13th Corps which had been left to hold Tobruk during the retreat to El Alamein. We faced Rommel’s counter attack which had originally begun west of Benghazi around Xmas 1941 and had been halted for months at the Gazala line.

had been on a course at Base Camp in Almaza, Cairo, from 1st to 7th June (in lieu of leave, which was not allowed) and had returned to re-join the Battery outside the Knightsbridge Box where fierce fighting took place before we were pushed back to Tobruk. Some days later the Germans attacked the town. We were in the South West of the perimeter and did not see the prong of the attack which came from the South East. We were well dug in, in front of the infantry with some South African anti-tank guns from the 2nd S.A. Division, composed mostly of Africans in whom I had little faith. In the event, they put up little resistance and we were easily over-run around 11 a.m. when the temperature was about 120 degrees.

Late the previous day I had been strengthening our observation dug-out with some telegraph-like poles which I had managed to scrounge. We had been going back and forth to collect these when there was a large explosion between my leg and those of my O.P. ac. [?] This resulted in his right leg being blown off at the knee. I was unhurt. We claimed he had stood on a buried mine from the previous Tobruk siege but it could have been through enemy action on that day. I treated his leg with a tourniquet and the following day he was captured as indeed we all were during the course of the day. I understand he was well treated, taken to hospital, then transferred to prison camp in Italy, from which the Red Cross had him repatriated. He made a good recovery, eventually returning to his job in a Liverpool bank.

The rest of us, having been surrounded by German Infantry, were heralded into a Square with a large number of Germans guarding us. Some of our men had managed to get away on some Guards Division lorries by jumping on to them as they sped past. I actually managed to touch the side of one of the lorries but failed to get aboard. In the event, we were marched into a wired enclosure from which there was no chance of escape. We spent two days there before the Germans handed us over to be guarded by the Italian troops. We were then transported by lorry back towards Benghazi, then to Italy.

From the time we were given over to the Italians it became impossible to make any attempt to escape since we were under observation by a large number of soldiers at all times. Also, they were on a ‘high’ because at that time they appeared to be winning the war and were inclined to be trigger happy, especially since they knew we could not shoot back. The Germans, of course, were happy to be relieved of the responsibility of looking after us and to be able to proceed with their main objective – the march to Cairo.

We had found the Germans to be good soldiers and always fair in their treatment of us. The Italians on the other hand, were poor soldiers and enjoyed the bullying.

[Digital page 5, original page 000004]

[Subtitle]JUNE – JULY 1942 Tobruk, Derna, Barce, Lecce.

In the cage in Tobruk we found most of ‘C’ Troop and Battery Headquarters of 234 Battery 68th Medium Regiment. At this time I was Troop Leader of ‘C’ Troop though previously I had been with ‘D’ Troop.

‘D’ Troop had not been inside the Tobruk perimeter and so had not been captured. Eventually, they had made their way back as far as El Alamein and were later absorbed into 64th Medium Regiment, Royal Artillery which had also lost one troop in Tobruk. The remainder of 68th Medium were ‘in the bag’, including Regimental Headquarters and 233 Battery which had been equipped with 6-inch Howitzers and commanded by Major Bobby Burton, with whom I was later to be associated in the post-war Territorial Army.

After some days surrounded by Italian soldiers in the Cage at Tobruk, from which no-one, to my knowledge, ever escaped, our removal to Italy was commenced. The first stage was by truck to Derna, where on arrival we were held in an old fort at the top of the escarpment. Only a small number, perhaps 100 or so were moved at a time. The weather was very hot, around 120° with no shade. Morale was very low all during this time, food and water rations being negligible.

We were kept standing in the sun for many hours. A number of officers fainted. The sentries were coloured Italian troops, possibly Libyan mercenaries. They were quite brutal. Anyone stepping out of line got hit with the butt of a rifle. Those who fainted were left to lie where they fell. I saw two officers begging for water. Both were hit over the head with the butt of a rifle and both died. Later that day we were moved in trucks to Barce.

At Barce we were put in a cage with tents of the cottage type for accommodation. Memory tells me we were kept here for approximately two weeks. We had water and food sufficient to keep us alive. I don’t remember any bread but we had small tins of meat, comparable perhaps to our own bully beef.

Here, also, we were given a printed Red Cross P.C. [postcards] coloured orange, which simply said we were prisoners. We were told to address this to our next of kin, and to fill in our Army number, name, rank and Unit. Needless to say, we entered only our name, number and rank. My P.C. was eventually received by my sister to whom it was addressed.

Conditions were not too bad though we only had what clothes we stood up in and could not wash. It was very hot and, apart from the tent, no shade.

The next move was from Barce to an airstrip at or near Benghazi. We were put aboard an old Savola Caproni three-engined bomber. Each plane held fifteen prisoners, seated along the fuselage. Guarding us were five Italian soldiers, each holding a long, old-fashioned rifle with fixed bayonet. The bayonets were about 18″ long, and together with the rifle would be around 5′. The pilots compartment, housing pilot and co-pilot, was screened off from us by an unlocked door.

Our fifteen were made up of fourteen army officers and one RAF pilot. The Italians did not realise that one of our number was a pilot, since he was dressed in khaki shirt and shorts the same as the rest of us.

[Digital page 6, original page 000005]

The side doors of the plane were left open in flight and the sentries stood looking out. Since we were flying over the Mediterranean en route to Italy we formed some wild schemes to overpower and throw them into the sea below. However, among us we had a Lieut. Colonel, who was senior officer in the party. I believe he was RAOC and had been in charge of a clothing store in Tobruk. He forbade us to try this, it being too dangerous for all concerned. It had been part of our plan to take over the plane and for our Air Force Officer to fly us to Malta. If and when we reached there, we planned to tie our shirts together to form a streamer to hang from the doors of the plane to indicate to the gun happy Maltese that this was an enemy plane with a difference. However we were prohibited from doing any such thing and eventually landed and were taken to a converted warehouse in Lecce in the southern heel of Italy.

I may say we had thoughts of throwing the Colonel out of the plane too, since we felt the possibility of escape had been missed. However, it could have failed and we would never have had another chance.

[Digital page 7, original page 000006]

[Subtitle]AUGUST 1942 P.G. 75. Bari, Italy.

We had been kept in Lecce for a few days only, after which we were taken to the Railway Station and entrained in reserved compartments for somewhere up North. Immediately our thoughts turned to the possibility of jumping from the carriage windows but this was ruled out for various reasons. Apart from being extremely dangerous to life and limb, we were in the very south of Italy with the Mediterranean behind us and a hell of a long way in front, inhabited by what, at that time, was a very belligerent population. In any case, each POW Officer was still being guarded by two Italian soldiers, and it was felt that any attempt at escape should have been tried before leaving North Africa. As it was, Switzerland would be the nearest neutral country.

The train chugged northwards, stopping at innumerable stations where more people boarded and some alighted. The civilians all looked reasonably well off. I can’t remember how long the journey took, but eventually we arrived at the Adriatic port of Bari. From here we were transported to our first permanent camp – Camp Prigioneri de Guerra 75.

The camp was a wooden hutted one. Each hut accommodated about 60 officers in two close rows of double tiered bunks, fifteen each side. We had two blankets and two sheets each, plus a straw mattress and pillow.

Most of the Officers were British but there were some South Africans and New Zealanders.

Food came in the form of a watery vegetable soup and a loaf of bread (what we would call a dinner roll) each. Around 11 a.m. each day the rations would be delivered. The bread presented no problem but the soup was delivered to the door of each hut and the Senior British Officer in the hut detailed two junior officers to dish this out to the inmates who queued up to be served. A ladle was provided to dish out but the quantity varied each day and while it was accepted that each should receive one ladleful, there were days when it did not go that far and some had to go without. On the days when there was more than enough it was accepted that the server could have two ladlefuls and give the rest to whoever he chose.

On the day I had to dish out there was plenty, so I and the bread man got two helpings and we gave the rest to whoever was nearest. As I walked back to my bunk I heard some remarks coming from two South African Boers and while I did not know the language, I could recognise the universal swear words and realised they were accusing me of being unfair in the distribution of the soup. This led to words, then to fisticuffs and while I don’t suppose there was a winner, I didn’t do too badly.

This petty incident did show the high tension which existed in those early days. Morale was very low and tempers easily frayed. It also showed the bad feeling between the British and the Boer South Africans whom many of us blamed for the surrender at Tobruk where the 2nd S.A. Division formed the major part of the Garrison under the command of General Klopper.

The 1st South African Division were mainly British South Africans and was a good division. The 2nd S.A. Division were mainly Boers, many of whom had strong Germanic sympathies.

[Digital page 8, original page 000007]

The camp was very heavily wired and remained heavily guarded so morale sank to a very low ebb and even if we had got out there really was nowhere to go. Internal camp organizations never got off the ground here so there was nothing to do but lie on our bunks and sleep most of the day.

Red Cross Parcels were non-existent at this time. We had no books or playing cards. There were no exercise areas and it was very hot.

In due course, after four or five weeks, we were on the move again to a more permanent camp.

Little did I dream that some eighteen months later I would return to this same camp but this would be after my successful escape and when I would be on my way home. At this time, the camp was being used as a Transit Camp for escaped POW, and where we would be kitted out with new battledress, boots, toilet gear etc. It would also be used as a staging post for foreign personnel who had been detained by the Italian State and were now classed as displaced persons under the care of the Allies.

[Digital page 9, original page 000008]

[Subtitle]SEPTEMBER 1942 P.G. 21, Chieti, Abruzzi.

After about a month in Bari, we were transported to Chieti, in the Abruzzi region.

I find it hard to remember much about the journey. Again we were taken in trucks to the railway station at Bari where we were put into reserved carriages at the tail of an ordinary train. The people I remember on the platform looked fairly well dressed and fed. Most appeared hostile towards us. This was a corridor train, eight to a compartment, a sentry with rifle outside each.

The route took us up the Adriatic coast, through Foggia and Termoli to Pescara. We stopped at Foggia which had a fairly large station and many people on the platform. We appealed to some, particularly to the ladies for food, chocolate or cigarettes, but each time our sentries would intervene and push us back into the compartment from which we were forbidden to leave. They would pull down the blinds and we would put them up again.

At this point in time the Germans, and with them, the Italians, were knocking at the gates of Alexandria and Cairo so the whole of the Middle East was their oyster.

I did hear of a group of three or four prisoners jumping from the train but I never heard how they fared. Personally, I felt that since we were on a train going North, we would be better to get as far north as possible, the nearer to Switzerland the better, but of course we had no idea where we were being taken to.

On arrival at Pescara (though we did not know the name of the place at that time) we had a long wait before we realised that the front of the train had gone on and we had been left behind. After a long delay, another engine was hooked on to our carriages, we were shunted up and down, eventually continuing our journey, but this time in a Westerly direction. We realised of course that we had travelled about halfway up the main leg of Italy and were now going in the direction of Rome. After a very short time and indeed only about 15 miles further on we stopped at a wayside station called Chieti Scalo and ordered to get out of the train. We were marched down the main road with about as many sentries as prisoners on either side of us. About 500 yards further on we turned right, through a main gate and into an area with a twenty foot high wall all round. This was to be our home until September 1943.

Inside the twenty foot high wall was a reasonably modern barracks complex of six main buildings and a cookhouse. I must have spent approximately a year in this Camp, referred to as P.G. 21.

Writing this in 1993, 52 years later, it is impossible to remember all the details as they happened and names of other officers who were with me. However, I shall endeavour to describe some places and events which stand out in my memory, although not necessarily in chronological order.

Firstly, the situation of the camp was very pleasant. To the North we could see the Gran Sasso, a range of mountains with the highest peak being of that name, covered with snow in winter. There were beautiful sunsets both winter and summer and so the artists among us made full use of their talents.

[Digital page 10, original page 000009]

On the other side and more to the south we had the town of Chieti on a peak and its cathedral well to the fore. We could see the road winding up the hill to the town and alongside ran the electric tram-car. This used to wind its way up the hill making clanging noises and sounding its bell as it rounded the bends. At night, in the winter, we could see blue sparks from its overhead wires. I used to think I would love to see this town one day and see it I did when I returned there with Catherine many years later. By that time, however, the road had been re-aligned and the tram-car no longer existed. It was very interesting but had lost some of its charm. The hillside up to the town was terraced with vineyards and olive groves and dotted with farms. Many times, when planning escape, I had considered this as my Stage 1. and it did indeed prove to be so.

Each of the six buildings had been constructed in a U shape, with an entrance hall at the front and a number of rooms allocated to officers of Major rank and above. Along each leg of the U shape ran a central passage with six rooms on either side. Each room contained ten double bunks, so there would be twenty on either side of the central passage. Each side had two wooden barrack room tables and trestle seats, also a wood burning stove, but no fuel. The stoves were flued by a stove pipe leading into the hollow bricks, the theory being that they would provide a form of central heating. On the odd occasion in the winter when we were able to scrounge some timber, this was most acceptable and we made good use of the stove.

After the six rooms mentioned above, there were another two, one either side. On the left we had the toilets, which consisted of about a dozen tiled bases with a place for each foot, and a hole in the middle which served as the ‘pan’ but no water available to flush. There was a well in the courtyard from which we collected a bucket of water (provided of course the well had not dried up) and threw its contents down the toilet.

On the right, opposite the toilets, the room contained a line of cold water showers and a row of toilet basins, complete with tap fittings etc. but generally no water. They did turn on the water for five or ten minutes each afternoon around 4 o’clock, during which time 240 of us were supposed to wash, shower and shave. Naturally, by guile and other means, we managed to make do by filling a bucket and using up the water from the well.

In another building, one of the legs was used as a dining area and we were allocated our times for using this.

It should be understood that all internal discipline was run by our own command and the S.B.O. (Senior British Officer) was the most senior ranked prisoner held. In our case, he was an Indian Army Officer, Lieut. Colonel, and we were under British Military Discipline.

At breakfast time we were issued with a small roll of white bread and some black Acorn coffee which took a bit of getting used to as it had a very bitter taste. Later in the day we had a plate of watery vegetable soup. These could be supplemented by Red Cross food parcels, when issued. In fact, we had been there for about three months before receiving any, then three weeks running we’d receive them. These parcels were most welcome when issued but supplies were sporadic. When in good supply, certain items would be removed and given to the cookhouse to prepare as bulk meals. The rest of the contents were given out individually. These included butter, biscuits, condensed milk, chocolate, jam, marmite etc. and these we could eat as and when we wished.

[Digital page 11, original page 000010]

There were spells when the parcels were not split up but were issued unopened. In many ways this was preferred as there was a lot of mistrust, jealousy and suspicion in the camp. It was believed that cookhouse staff and others got more than their fair share if the first method was adopted. There was also a fair amount of pilfering and dishonesty among the 1500 or so officers in the camp, and it was not unknown for a Court Martial to be convened.

In the main, however, though there were spells of near starvation, we managed to be well satisfied on the whole, and perhaps health today would improve if our eating habits more closely resembled those days of scarcity.

It was probably around November 1942 that I was invited by Lieutenant Hugh Gordon Brown of the Northumberland Hussars, to join an escape organisation. Originally, there were about ten in the group, but when plans got under way this number was increased to about forty. At this time I was working with a young regular Royal Artillery 2nd Lieut. Tony Gregson, a Scotsman from Tarbert in Argyll. Six of us were formed into digging groups, initially in twos, working a morning, afternoon and evening shift. This was called the underground shift. In addition, it was necessary to have an extensive above ground shift of watchers, placed all around the camp, to warn immediately of the approach of any Italians entering the compound. If this happened, we had to stop work immediately and camouflage the area we had been working on to avoid its detection. The first site we chose was in the latrines, this being the nearest site to the outside wire and wall and where we would be out of sight of the guards on top of the wall. To start with, we had to remove some floor tiles, but we also had to have some spare undamaged tiles to replace any damaged on removal, in the hope that our work would go undetected by the Italians who regularly sent round a search party of one officer plus two or three soldiers who carried long hammers like those used on railways to sound the rails. With these, they tapped the floor, listening for any hollow sounds or hoping to find loose or damaged tiles. Our first attempt only lasted about a week before it was discovered and we hadn’t even reached the foot or so of concrete underneath, but we did manage to hide several unbroken loose tiles which we were able to keep for future use. No punishments were meted out but we were subjected to lengthy roll calls which caused inconvenience to the whole camp and which, in fact, caused ill feeling with some who had no intention of trying to escape and for whom the ‘war was over’. Anyway, with the benefit of some ‘experience ‘ behind us we made plans the next day for a new site.

Our second attempt got underway a few days later, inside one of the barrack rooms which lay more or less opposite the one in which I had my bunk. The team was the same as those involved in the first attempt. We were led by Hugh Gordon Brown, 6’6″ tall, and a great leader. He had the full confidence of all taking part, including the Escape Committee and Senior Officers in the know.

To start with, we had to break through the ceramic floor tiles laid in cement on top of a concrete base about 15″ thick. Digging tools used were odd pieces of metal gathered from around the camp and a few large granite type of stones to use as hammers. Progress was very slow as we attempted to remove tiles from an area of about 2 square ft. and replace the ones broken in removal by new ones relayed to the site and of course we had to camouflage the site each time we had to stop work. Stoppages took place at roll calls, meal times, sudden spot checks and at night time. We had also to earn the patience of the residents of this room who were not involved in the escape process.

[Digital page 12, original page 000011]

Digging proceeded over several weeks and we were still slowly clawing our way through the concrete. A lid of new tiles had been constructed and was put in place over the space left where the concrete had been removed each time a warning was received that the spot check team were on their way. Then one day, after such a warning, the lid was put in place, camouflage completed and team dispersed. The spot check team tapped the floor with their long hammers, listening for hollow sounds, looking under beds and slowly moving through the building until they came to the room of our labours – Captain Cruce, the Italian 2 i/c [Second In Command] a Fascist, the Interpreter Lieut. and two hammer boys. Bang in the middle of the lid, a soft hollow sound, and wet cement. And so the project was exposed. Nobody would admit liability and so it was decreed that all the occupants of that half of the room would be held responsible. The sentence was seven days solitary confinement in the cooler and they were told to report at the white line inside the main gate at 6 p.m. with blankets. They formed three ranks, complete with beds and bedding, outside the building at 5.30 p.m. and the whole camp turned out to line the route to the main gate to which they marched, cheered, and led by Major Stuart Hood of the Black Watch playing the pipes. So ended our second attempt.

It took some time to determine the 3rd attempt and have it approved by the Escape Committee, still under the leadership of Hugh Gordon Brown. A site was finally selected, outside the building, in the courtyard. The building was surrounded by a concrete pathway, the edge of which had a concrete type of kerbstone. Six to nine inches lower than the kerbstone ran a rainwater gutter, which allowed the rainwater to flow into drains at the side of the kerb. The water then dropped into a sump and eventually drained off into the ground. The sump had a square manhole lid on top, approximately 12″ sq. and level with the walkway. The sump itself, which was rather bigger, was made of brick. The lid had a little hook, fitted flat in the centre, to enable removal of the lid. This lid, situated right outside our barrack room window, I ‘m sure had never been lifted since construction until we investigated what was underneath. The site was situated in a similar position to Tunnel No. 2, but outside in the courtyard, also out of sight of the sentry on top of the wall, but of course sentries patrolled in pairs constantly, inside the wall, and so our activities had to stop each time they approached. Our outside security system had to be fairly elaborate. It was about the end of March or early April before our operation got underway.

To start with we had to remove some of the bricks from the side of the sump nearest the wall but we had to be sure that the sump still functioned as a retainer for the rain water. Then we dug what we referred to as Chamber No. l, to enable us to slide feet first into it, get underground and replace the lid on top of us. We also kept a supply of grey dust to be brushed over the lid each time it was put back in place and hopefully concealing the operation. We also planned and operated a system of spreading a blanket on the pathway and on which one or two of our members would sit, backs to the building and be reading, drawing or painting or any other such activity. In April this was not so easy, as the weather was still quite cold, but later as it grew warmer and standard dress was shorts only, one could sunbathe without drawing attention. The construction of Chamber No. 1. took about five to six weeks to construct. We worked in three shifts:

- Morning. After first roll call until 12 noon.

- Afternoon. From 2 p.m. until evening roll call, around 5 p.m.

- Evening. Usually lasting about one hour but mostly confined to a disposal fatigue, to get rid of the day’s spoil.

[Digital page 13, original page 000012]

In the courtyard was a large well which was filled by underground seepage. This water was used for washing only, not for drinking. There was rationing of course and so it was used mainly to keep clean and to wash the few clothes we possessed. To begin with we used the well to dispose of the diggings from Chamber No. 1, but there were complaints from non-tunnellers that we were fouling the water to such an extent that it was no longer usable for washing purposes. Remembering that there was only about 10 per cent of the POWs interested in escaping, it was not surprising the resistance which arose when normal routine was upset by our activities. We had to stop using the well and make other arrangements for the removal of the diggings.

[Digital page 14, original page 000013]

[Subtitle]SOME EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES AT CAMP P.G.21 – CHIETI

Arriving here in the autumn of 1942, we were dressed in Western Desert type clothing, suitable for the summer weather in that area. I had a shirt, shorts, a pair of socks and desert boots. I also had a desert bush jacket, in the pockets of which I had a silver cigarette case, and a Westclocks Travel Alarm. I was wearing a wrist watch. I had managed to conceal these items before being searched by my captors who were looking for such items and for any small arms which we may have concealed on our person.

With 1500 Officers in the camp it was not surprising that many organized different activities and although my principal object was to try to escape I felt it was necessary to participate in these activities also, so that I could keep fit both mentally and physically to be successful in any attempt.

Music was one of the main entertainments. Tommy Sampson, the Jazz Band leader, brought in with him his cornet so it was not long before he had in rehearsal a Jazz Band. A piano was supplied and from somewhere a Big Bass appeared, followed by Saxophone, Drums and other instruments, so swinging was the order of the day. Likewise, we had Tony Bains who had been a bassoon player with the London Philharmonic and in no time at all we had the semblance of an orchestra playing classical music. The Camp Commandant and Interpreter must have helped with all this and it was surprising what a few bars of chocolate or a tin of coffee could obtain. These items of currency, of course, came from Red Cross parcels, the contents of which were sometimes used for other than sustenance. Bains organised regular orchestral concerts and Sampson gave Jazz sessions and afternoon “tea dances” on the patio outside the cookhouse. On one occasion they organised “night club” which we attended suitably attired, some dressing up as females. For this event we had saved our weekly ration of Marsala Ouva to get us in the mood. A popular item was “Greta Garbo” singing Lili Marlene.

There was also a Drama Group which put on a weekly show. I don’t know where all the scripts came from but the Red Cross no doubt helped and when mail started to come through, family, friends and local organisations all helped by sending a variety of things.

A “University” soon got going. A number of teachers, University lecturers, and professors in our ranks, organised the teaching of any subject requested. Many sat official professional exams, such as Bankers, and there were numerous non-vocational courses of single or half a dozen meetings.

Sport of course featured prominently. The grounds were spacious but not designed as a sports field. Between the buildings there was a wide tar-macadam path with concrete rain water channels running down either side. Young trees, supported by stout poles, had been planted in this area. A number of these were “accidentally” broken and so here we played football in the winter and cricket in the better weather. In cricket we were fortunate in having Bill Bowes of Yorkshire and M.C.C., also Freddie Brown of Middlesex and M.C.C. so we had regular league matches between “Yorkshire” and “Middlesex”.

Later, when American prisoners started to arrive, some of them were taught by us to play cricket, and they taught us baseball.

Another activity was gardening. Some, but not I, took quite an interest in growing vegetables from seed provided by the Red Cross. My interest in the garden was that it provided a safe place to dispose of the waste from our tunnelling.

[Digital page 15, original page 000014]

Learning languages was an important occupation, especially Italian for the would-be escapers. I managed a fair command of it, but not so good as some of my accomplices.

The Church too, played a part. We had a minister of the Church of Scotland who took regular church services. He was from Gourock and I heard later that he had been transported to Germany where he became very depressed and unwell. We also had an English priest of the Church of England and later an American Roman Catholic priest.

We were taken out of the Camp only twice. On the first occasion we walked up the road towards the town of Chieti. This was early after my arrival and I reconnoitred a culvert under the road which I planned would make an early hiding place should I ever escape. In fact it was used by me a year later when I did escape. Years later I was able to show it to Catherine when we returned to the site of the camp. On the second occasion when we were taken out for a walk we only went a few hundred yards from the gates to a stream where we were able to have a swim and this was most enjoyable. We were asked to give our word that we would not try to escape on these outings. This we would not do, hence the reason we were only out twice in the year with, on both occasions, two armed sentries to each officer. This made walking less enjoyable since they were nasty, scruffy little men.

The playing of Bridge became an important part of most days and I became rather proficient at the game.

Before concluding this chapter, I must refer again to two of the personal items mentioned at the beginning, namely, the silver cigarette case and the alarm clock. Sometime before the end of the war, they were discovered by one of my fellow officers, lying on the floor of a surplus clothing room in a camp in Germany. He concealed them, managed to bring them home at the end of the war and returned them to me in Newcastle on his return.

[Digital page 16, original page 000015]

[Subtitle]THE SUCCESSFUL TUNNEL.

The site for the third attempt took some time to select and to get it approved by the Escape Committee. Still under the leadership of our ” above ground” Manager Lieut. Hugh Gordon Brown the site was finally selected outside the building in the courtyard.

The building which was constructed in the shape of a letter “U” was surrounded all round its exterior by a concrete pathway. The outside edge of this had a concrete type kerbstone edge to it and again all round this and about six to nine inches lower was a concrete rain water gutter. This allowed the rain water to fall into drains in the side of the kerb. The water then dropped into a sump and eventually was drained off into the ground. The sump had a square manhole lid on top level with the walkway which was about 12 inches square. The sump which was rather bigger was constructed of brick. The lid had a little hook fitted in the centre and not protruding to enable it to be lifted out. I don’t think this one which was situated right outside our barrack room window had ever been off since constructed until we investigated what was underneath. This was situated in a similar position to tunnel No. 2 but this time outside in the courtyard. It was out of sight of the sentry on top of the wall, but of course sentries patrolled inside the wall in pairs constantly, and any activity by us had to be concealed each time they approached. I will describe later our outside security system which had to be very elaborate. It was about the end of March 1943 or the beginning of April when we commenced operations.

To begin with we had to remove some of the bricks from the side of the sump nearest to the wall, but still to leave the sump functioning as a retainer for the water draining if it rained. Fortunately, we started at the beginning of the summer and dry season so there was very little actual rain. Only occasionally did we have substantial thunder bursts, which though heavy did not last long. Then we dug a chamber (Chamber No. 1) to enable us to slide feet firs~ into it and so get underground. Then when the space was big enough for one man the lid was replaced on top and closed. This man then worked away on his own until it was big enough to take two, and so on. We also had a supply of grey dust to brush over the lid each time it was closed to camouflage the operation. We had to work a system to spread a blanket on the pathway over the lid, and one or two members would sit on this blanket with their backs to the building wall and appear to be reading a book or drawing, or painting, or some such activity. In April this was not so easy as the weather was still quite cold but later in the year when the summer weather was warm and the standard dress was shorts only one could sunbathe without drawing attention.

I cannot remember exactly how long it took us to construct the Chamber No. 1 to completion but it was probably about 5/6 weeks or so. We worked in three shifts.

- Morning – after first roll call to about 12 o’clock.

- Afternoon – from about 2 p.m. to before evening roll call, which was usually around 5 p.m.

- Evening – usually about 1 hour only.

[Digital page 17, original page 000016]

but it was hardly worth the effort to get the organisation installed that this was frequently confined to a disposal fatigue to get rid of the day’s spoil.

In the courtyard was a large well which was filled by underground seepage and this water was used for washing only. Not for drinking. There was no rationing of its use and people used it to keep clean and to wash their clothes – such as they had. To begin with we used this well to dispose of all the diggings from Chamber No. 1 but we got complaints from non tunnellers that we were fouling the water and it was no longer usable for even washing purposes. Remember, there was probably only about 10% of the POW interested in escaping and it was surprising the resistance which appeared if we upset the normal routine of the running of the Camp. We had to stop using the well therefore and let the sediment settle again and make other arrangements for the removal of diggings. Also with the summer the water level in the well got steadily lower due to the dry weather.

Now to remove the earth we made long sacks which were joined by braces which hung round our necks and underneath each trouser leg. The earth was brought up in empty Red Cross Boxes from which the sacks were filled. By pulling a string it opened the bottom of the bags, the earth dropped down inside our trouser leg, fell to the ground and was trampled or raked in. Sometimes the squad working on the camp garden would be ready with rakes and we would drop the soil where they were working and they would rake it in with the existing. It was surprising that the Italians never questioned the fact that the same piece if ground was constantly dug over with nothing growing.

The tunnel progressed slowly inch by slow inch. At the end of the concrete walkway we had to drop its depth under the ground to about 6 feet. To do this we dug chamber No. 2 where two people could stand up and turn round before proceeding outward towards our goal. This in fact became the forward command post from where operations outside the walls and wire commenced. We constructed some supports from bed boards but a great deal of the way we “trusted to luck and the Grace of God” that it would not cave in and collapse.

Most of the time we got away with it but we did have a collapse and fall in at one point, with a body trapped on the outer side and we had to work hard to clear it and get him free. This we did and then put in some extra supports in that area.

We were now proceeding at a depth of about 6 feet under the internal pathway under the trip wire inside the wall, and then under the wall itself.

About 6/8 feet past the wall, the foundations of which we identified, we came up against a brick wall. We tried to dig under it, and then over it but we removed all the earth from that side of it facing our approaching tunnel. Then we chipped away at it and eventually managed to remove some of the bricks and we discovered that it was in fact a sewer the internal measurements of which was about 2 feet. Our first reaction was that this could be our route to escape and that we would not have to dig any further. It was however a very small square and very smelly but we squeezed a small man inside and sent

[Digital page 18, original page 000017]

him off to investigate. He had with him a small olive oil lamp with a naked flame to give him some light. After crawling a good way there was a flash and a bang. The lamp had ignited the sewer gasses which had exploded and he was very badly burned. Another man had to be sent down in the darkness to drag him out. He was burned and in considerable pain but fortunately not life dangerous. He was dragged right out of the tunnel, through Chamber No. 2 along to Chamber No. 1 and up and out, without giving the project away. Arrangements had by this time been made for first aid. He was carried over to the cookhouse where the cooks spilled a can of oil over the stove to cause a large fire. This brought out the Italians who accepted the man had been burned from this “accidental” fire and he was taken off to the camp hospital from where he was discharged a week or so later.

We gave up the idea of using the sewer as an escape route but we then brought it into use as a disposal area for the digging spoil. The sewer was boarded over for about 50 feet or so allowing the sewer waste to flow under and with two men inside equipped with a sledge with ropes on either side the earth was pulled in by one and stacked inside. The empty sledge was then pulled back to be re-filled. As the space inside was so restricted small very small men had to be used for this job and they became to be called “The Sewer Rats”. This did away with the gardening parties.

Now I must talk about ventilation.

[Digital page 19, original page 000018]

[Subtitle]VENTILATION.

The Tunnel had now got so far from where there was an air vent and there was a second air vent at the end of the pathway which equalled to the corner of the building before the path which equalled to the corner of the building before the path which surrounded the complete camp. This would be about a distance of thirty to forty yards. At this point a further chamber was dug six feet deep and from that point the tunnel proceeded at a much deeper depth than originally in order to get under the wall and to ensure there was sufficient above the tunnel to avoid cave-ins. From here onwards we found the lamps we used to light our way would hardly burn because of lack of oxygen. We ourselves found that breathing was starting to become very difficult for the same reason, and therefore we had to think about some artificial form of ventilation.

This we did by making a pipeline constructed out of Red Cross meat tins joined together to form a continuous pipe.

We found that little meat or fish paste tins, cheese tins which were included in the Red Cross parcels would fit exactly inside Spam tins and meat loaf tins so these were inserted half way into the end of each tin, the next tin fitting over the other half. So we managed to contrive to manufacture a continuous pipeline. Needless to say the whole camp was scoured to find empty meat tins in order to get sufficient, and those prisoners in the camp, all 1500 of them were forbidden to destroy their tins by tramping on them, to supply them to the CAMP ESCAPE Committee for this purpose.

The back at the original opening one of our clever engineer type members contrived to manufacture a pump. It looked like a kit bag. It was made of canvas material. He constructed valves into it so that when it was drawn out it would fill up with air, and when it was pushed in air was pumped through the pipeline to the digging face, and in this way we got sufficient air to keep us going. It did not provide a great quantity of air, but it was rather fascinating to watch the little Olive Oil tins which had a piece of string in them in order to provide us with a wick. They would flicker down to almost nothing and when the operator back at the origin of the tunnel forced the air down through the pipeline the wick would flicker up and give quite a decent light – lasting for two or three minutes and down it would go again. An up and down lighting system. Very effective but the other point is that it gave us just sufficient air to keep us breathing and alive whilst digging at the face of the tunnel.

[Digital page 20, original page 000019]

[Subtitle]OPERATIONS EARLY AUGUST TILL 8th. SEPTEMBER 1943.

During this period, work proceeded steadily. With the opening up of the sewer it made the disposal of the diggings much easier and much more rapid because whilst we had two men in the sewer packing the earth away we did not have the extra distance to cart the diggings in boxes back to the opening and stack it up there until we got the opportunity to take it out of the tunnel and spread it on the earth outside. This saved a lot of man hours, less personnel required and was much speedier. During the month of August the tunnel had kept steadily advancing out towards open ground beyond the walls of the camp. We were planning to surface on or about the 20th September and I had been planning to go with Tony Gregson down to the coast to try to steal a boat of some description to cross the Adriatic Sea to Yugoslavia. But that is another story which did not come off. I can’t remember just when Tony was moved out of the camp and sent to another near Bologna so he was no longer with us and I teamed up with his replacement – Guy Weymouth.

We had one quite severe earth fall at one point where we had not been shoring it up with wood. There was no injury to anybody, but it gave us a fright and showed us what could happen if we did not look after it properly.

The area tunnelled would be about roughly 2 1/2 feet wide by about 3 feet deep in their words just a hole prodding its way through the ground. The digging tools were largely just a sharp piece of metal to dig the earth out, and our hands and fingers to lift it up and put it in boxes. Empty Red Cross cardboard boxes were used for this purpose. I suppose we proceeded outwards at about a couple of feet per day. Work also proceeded at this time for those of us who wanted civilian clothes or false uniforms, to collect our food boxes, get them packed and have them ready for the final day when we could come up to the top, smell the open air and start to try to make our way back to the U.K. and home.

This went on steadily till the 8th September when a new paragraph in our escape story commenced: THE SURRENDER OF THE ITALIANS TO THE ALLIES.

[Digital page 21, original page 000020]

[Subtitle]8th. to 22nd. September 1943. 2 n

On the morning of the 8th. September the Italian radio which forth music. It broadcast to the parade ground was blaring suddenly stopped and there was a lot of talking in Italian, and then we heard from our interpreters that Marshall Graziani was to make an announcement. This announcement duly came and was to the effect that the Italians had surrendered to the Allies and had agreed to cease fighting against the Allies and to ensure the safety of all prisoners of war in Italian hands. Obviously, there was a lot of immediate jubilation amongst us because we saw that at last the end of the war with Italy had arrived and we could expect to be on our way home in the near future. We, who were members of escape clubs, tunnels, and other means of hoping to escape from custody immediately sent our senior representatives, in our case Lieut. Hugh Gordon Brown to the Escape Committee to ask permission to leave the camp by the front gate. This permission was refused and we were ordered to remain within the confines of the camp and that the Senior British Officer (S.B.O) Lieut Col. Marshall would be making an announcement on parade during the course of the day. He subsequently made this announcement to the effect that officers were confined to within the walls of the camp, were forbidden to try to leave the camp by any of the escape methods or out of the gate. He had apparently received an order in code from the War Office to this effect and he was obliged to obey the orders he had received and which had been fully accredited. It is now believed that this order was made by Lt. Gen Bernard Montgomerie, in command of the 8th. Army because he did not want any POW roaming the countryside and getting in the way of the FAST advancing armies which had landed in the toe of Italy. We protested about having to comply with this order but to no avail. In our own escape club we held a council meeting of all members to decide what action we should take. We did not believe that the Allied Armies would reach the camp before the Germans had time to re-organise themselves and move us to Germany, and so we decided the best thing we could do whilst obeying the orders was to develop the first 40 or 50 yards of the tunnel into a large open capacity in which if necessary we could hide in long enough as an insurance policy to let us get away safely.

One or two officers, American I recall, made an attempt to clear the wall and disobey orders. Being American they considered they were not under Marshall. They were re-captured by officers under orders from the S.B.O. and were placed under house arrest. In fact I think some of them were put in what had been used by the Italians as “the cooler”. The S. B. O. then organised guard duties by British Officers to take over sentry positions on top of the wall all the way round the camp. These officers were to sound a rattle if any POW tried to escape over the wall. It was a sad sight to see British Officers guarding other British Officers, however those of us who were members of escape clubs and who were making provision to prevent their removal to Germany were excluded from this duty, and we then set about to develop our own tunnel. This of course we did quite openly, with the lid at the entrance to the tunnel permanently open to allow adequate fresh air to enable us to work. We deepened the first 40 yards of the tunnel to around 4 feet deep by 3 1/2 feet wide.

[Digital page 22, original page 000021]

This gave us plenty of room to get inside without having to crawl on our stomachs as before. We also removed our own personal food parcels and escape uniforms into the tunnel as it progressed so that they would be available immediately if required. This work went on steadily day after day between the 8th. and 21st September. and it was widely recognised that it would be used if we had to. We also progressed the far end of the tunnel and made a large chamber at its present extremity and we started to dig upwards intending to get through to daylight without actually opening it up. We estimated we were about six feet under the outside ground level. To our complete surprise we had to dig 18 feet above the existing ceiling. We had in fact gone 10 feet beyond our survey and this had brought us into the side of a hill. The extra tons of earth we were removing as a result of this error had to be carted right back, taken outside, and camouflaged over the ground so as not to give the position of the tunnel should Germans enter the camp. If we had ever to use the tunnel to escape through the extra 10 feet of distance outside the wall would have given us much more cover. We did not in fact ever completely open up this far end, but only sufficient to ensure where we were, and to allow a free flow of fresh air right through the whole tunnel, which was now about 200 yards long. As the days went by through September, we were working away ensuring our future, but we were also getting the news of the Allied armies in the toe of Italy. All the time we were anticipating a fast advance. The Americans, who had landed near Salerno at Paestum were having a bad time and not making much progress. The advance up the leg of Italy was not proceeding according to plan. This alone should have given a message to the Senior British Officer (S.B.O.) that he should have got us out, but it did not do so. He rigorously stuck to his War Office Orders and retained us inside the camp. Feelings were running very high against the S.B.O. and his Adjutant etc. None of us attempted to disobey his orders. Food was still coming in to the camp and the stock of Red Cross parcels had all been distributed to the cookhouse and to individuals. We in the tunnels had been given escape rations sufficient for short time requirements.

On the night of the 21st. September all was quiet, and we retired for the night. The camp lights in the rooms were all out and things were quiet. Between 1a.m. and 2a.m. all hell broke loose. Lights went on throughout the camp and a company of German Paratroopers had marched in through the gates to take over the camp. This was what we feared would happen. As many of us as good made an emergency and rapid escape entry in to the tunnel before their troops came into our room. Only 15 of us made it when the lid was pulled down and we trapped ourselves underground. Some were too sound asleep, some were too far away, and some in fact resided in other buildings. Among those who were inside were, Lieut. Hugh Gordon Brown, 6’ 3’’ tall who had been our above ground manager. Lt. Guy Weymouth, Lt. Jas Cleminson who was later at Arnhem and myself. Other names I forget. Brown was killed later in a plane crash, Weymouth I have lost touch with, Cleminson was ADC to Gen Urquhart at Arnhem, later Chairman of Reckett & Colman and President of Confederation of British Industry. Through a vent we were able to keep in touch with Prisoners who were still in the camp with the Germans without them giving us away.

[Digital page 23, original page 000022]

Lieut Esplin, Quartermaster of my regiment, the 68th. Medium Regt. Royal Artillery, was kept by the Germans with a Rear Party to clear up the camp. It was he who was able to keep in touch with us who were below ground. He told us that a company of German Paratroopers had taken over the camp. That they had put guards on the walls with machine guns, that they had guards patrolling round each of the buildings inside the camp, outside the walls of the camp, and that the possibilities of escape were negligible. We could in fact hear their footsteps overhead. He said that it was their intention to remove all the prisoners in the camp to another camp not far away, and then on to Germany. We were advised to remain where we were and to keep very quiet. The move might take up to 3/4 days to complete. This in fact took place during the next 3 days and Esplin was kept with a small party to tidy up right to the end. He was the last to leave, but he was always able to keep us informed without the Germans knowing what he was doing. The prisoners were removed during this period to Sulmona Camp in the centre of Italy, truck-loads at a time. Esplin informed us that he would be the next to go and no one would be left behind. He would not be able to speak to us again. After a further night and most of the next day we lay quiet, listening for any footsteps overhead. When we decided there were none and the place was probably deserted we decided to put one of our members up to reconnoitrer and find out if the way was clear for us all to come up and get away without actually crawling through. He brought back the news that the camp was deserted, that we should come out and make our escape over the wall at the back of the camp behind the cookhouse. Apparently there were one or two other escapers in the process of doing just that. This we did. We therefore never actually used the tunnel to escape through, but we climbed up a ladder to the old sentry box, down the steps leading to it, and out into the countryside, separating into small parties. The allied armies at this time were held up well to the South of Italy. Whilst there were many Germans in the vicinity of Chieti, there were no organised armies nearby. And so after 15 months of incarceration in prison camps from North Africa, through Lecce, and Chieti, we were now free behind the two front line areas in Italy. We could now start to make our return to the U.K. and this story will continue to tell you how it was done.

I think it should be recorded at this point that out of 1500 officers in Camp 21 at Chieti, only 40 managed or even tried to escape that night. Many of the inmates considered that for them the war was over when they were captured and were quite content to sit the rest of the war out in captivity. They never considered the possibility of a move to Germany.

Footnote: The orders Lt. Col. Marshall received were that in event of an Allied invasion of Italy, Officers Commanding Prison Camps will ensure that prisoners remain within the camp.

Authority is granted to all Officers Commanding to take necessary disciplinary action to prevent individual prisoners of war attempting to rejoin their own units.

There is informed speculation that Montgomery, during a ‘working leave’ in London when the Tunisian campaign was coming to a

[Digital page 24, original page 000023]

close, instructed Brigadier Richard Crockatt, the Head of M. I.9 to use his secret channels to order all Prisoners of War in Italy to stay put in the event of a surrender.

After the war Marshall was called before a Court of Inquiry to answer for his actions and was subsequently exonerated.

[Digital page 25, original page 000024]

When we dropped off the bottom of the steps leading down from the Sentry Box we were free, outside the camp, for 15 months. We had been out of the camp twice before under escort. On one occasion we were taken for a march along the main road and through the village of Chieti Scalo and on up to the town of Chieti itself. It sits as many of these Italian towns do, on the apex peak of a mountain, with the spire of the Cathedral at the very top and seen for miles around. Guy Weymouth and I set off to walk not having made any fresh plans of where we were going other than to get away from the camp. We knew our eventual plan was to make our way South but in order to get our bearings and to get to know what we could about the local countryside we made for the road leading to the town of Chieti itself. It was a very dark night and apart from knowing the route from Chieti Scalo to Pescara and to Chieti we did not know anything about the countryside or the people or if there were Germans in the vicinity, but we assumed that there would be. The two of us proceeded up the road to find a culvert which I had observed on one of the two previous walks. We crawled into it, found it dry and clean, decided to lie up in it for the rest of the night, and find out our bearings in daylight. We also wanted to try to contact locals, hoping they would be friendly, and give us information to help us to form a plan of action. In the morning we made an investigation in daylight, keeping hidden so far as possible, to see just who were using the road. There were few vehicles using it but these included isolated German trucks which indicated there must be Germans somewhere near.

It was not long before we were spotted by some children who came to investigate us and spoke to us. We hoped they were friendly. They ran away but still we decided to stay put but to be on guard. We ate some of our rations and decided not to go on up to Chieti but to move more easterly towards Pescara sea and also the main North South Railway and Road system. Shortly two of the boys returned and told us Tedesci (i.e. Germans) were in the town of Chieti and now knowing who we were the warned us to be very careful. They also told us that we would be collected during the forenoon, and that we would be taken to a safer hiding place. They told us that the Allied Armies were advancing North and this information unfortunately helped us to form a plan of “wait and see”. Our thoughts then were that it could be only a day or two.

Two men later contacted us and pointed out a farm house not far distant, to which we were told to make our way through the orchards of olive trees. On no account to use the road. When we reached the house, a farm house, they were expecting us and took us straight to a very large haystack. There were two of them, both of which had been built on stilts. They were thatched right to the ground but in fact had a hollow base about three feet high. Underneath was nice and dry and warm with plenty of dry hay to lie on. We were put inside and the thatched door closed. After dark we were summoned out and taken into the house where a meal had been prepared for us. The food was good and welcome as was the red wine which accompanied it. Talking afterwards it was suggested that we should remain there for a day or two till the approach of the Allies was certain. Unfortunately we decided this was a good idea but in fact we might have been better to push off South straight away. Who

[Digital page 26, original page 000025]

knows. In retrospect however we had made the decision and we stuck to it.

This decision was quickly altered because two days later our hosts made it obvious that they were frightened by our presence and they wanted us to move on. They said that there were too many Germans about, that they would get into very serious trouble if we were found on their premises. Arrangements were made for us to move a mile down the road into the village of Chieti Scalo, very close to our old prison camp. We were to be housed in an out of use olive oil factory. We were also put in touch with some Partisan types who would help us and show us a route South to safety. The factory was a large building which was on the edge of the road from Chieti Scalo up the hill to Chieti and alongside the electric tramway railroad. We could look out from inside empty olive boxes, and see the people walking on the road and the passengers in the tram cars, and of course the vehicles passing. There were frequent German vehicles and some soldiers walking. They were never single but always at least two or three. It was suggested that we could hide if necessary in the cellar which was approached by a steel ladder through a trap door, but we felt this would be too much of a trap to re-arrest and we preferred to stay on top. Also a hand grenade dropped in by a searching German would be suicidal for us. Food was delivered to us each evening. We remained at this location for some days during which we experienced quite an earth tremor which shook the building and moved all the boxes. We knew that guides were being sought to take us on our way so we were content to wait for this to happen.

Now we were introduced to Francesco di Luigi, who was to be our guide for the first part of our journey. The following evening he took us out and across the road and into a third floor flat in a 5 storey apartment block. There we changed out of battledress into civilian clothes provided for us, retaining our army boots, and identity discs. We had coffee, some food, and they gave us some money before we departed, for which we expressed our thanks. We nonchalantly walked down the road, bought some grapes from a barrow, passed the entrance to the old prison camp and many German soldiers on the way. We were walking in the direction of Pescara. After about a mile, and slightly off the road, we arrived at the home of Francesca di Luigi. We were expected and a large meal had been prepared and was awaiting us. Near midnight we left in his company and proceeded to a pre-arranged meeting with another guide, half way towards Ortona. It was a dark night and we were unused to such exercise as walking cross country. The new guide whose name I do not recall took us on for a further two hours to a farm house. Here we were shown into an outhouse full of hay and straw where we were left and settled down to sleep till the morning.

We remained here, the end of our first walking journey, for several weeks.

[Digital page 27, original page 25A]

Approximate dates between 2nd – 8/9th October 1943.

[Subtitle]The Francavilla Affair.

Around this time our party which had escaped after the Germans took over P. G. 21 Chieti on 20th. September, consisting of myself (Lieut John R. Pennycook) and Lieut Guy Weymouth, Royal West Kents had been joined by Lieut Gordon McFall M.C. [Military Cross] R.H.A. [Royal Horse Artillery] who had separated from Capt Collingwood of the West Yorks because Collingwood was laid up in a farmhouse somewhere with Pneumonia.

We were sheltering in a hay shed belonging to a peasant (contadini) whose family were feeding us, a few miles inland from Francavilla-on-Sea.

Advice came to us to contact British Paratroopers who had landed nearby to assist escapers to get back. They advised us to meet at the mouth of the River Foro and that a boat would come in on the nights of 4th. 6th. 8th. and 10th. October to take off any escapers available.

We followed their instructions as did about 100 O.R. [Other Rank] Soldier escapers with the following results.

The Paratroopers were a detachment of the 2nd. S.A.S. [Special Air Service], a mixed French and British detachment, one of their Officers being Capt Raymond Lee of the French Foreign Legion.

On 4th. October our party along with about 6 S.A.S. including Lee and sergeant Johnny Cooper, crossed under the main coast road under a bridge through which flowed the River. No boat appeared and in the early hours we were told to disperse and to gather again on the night of the 6th.

This we did with the same results as on the previous occasion.

We gathered again on the 8th. with the same parties. The three of us went down to the beach, with the S.A.S. by the same route. Once there we spread out all on the South side of the river. It was fast flowing with a rocky under bed and deep in places. The O.R’ s were congregated all together on the landward side of the main road under cover of trees and scrubb country. The time would be between midnight and 1 a.m. The weather was dry and clear, possibly with a moon between clouds.

We were watching for a lamp signal from the sea, which was to be replied to in a similar way.

A noise was heard from somewhere on the North side of the River and Capt. Lee and two of his men crossed through the fast flowing and quite deep water to investigate.

It was not long before they realised it was a boat with several men on board and Lee called out to them. The reply was a burst of Light Machine Gun fire which was promptly answered by Lee’s men.

It was in fact a German E. Type Patrol Boat which quickly pulled out to sea out of range. They left the warm embers of a fire on the shore.

Lee returned to us and ordered us to disperse and sent one of

[Digital page 28, original page 25B]

his men to the large gathering of escapers on the other side of the road. They were ordered to disperse and to make their own way back to Britain, that the area was compromised and was abandoned. On the way to re-cross the River Lee found evidence that the crew of the E-Boat had been ashore and had a fire on the beach probably to cook some food or other.

Also at about this time one of Lee’s men, a German originally of the French Foreign Legion had accidentally fired his Sten Gun and put a shot through his own foot.

The three of us returned with Lee to the outhouse he had been living in, had a hot drink, made arrangements to contact later as we thought we could arrange a further “shipping ploy” and went off to our own shelter some miles away. Our contadini friends were surprised to see us back the next morning.

[Digital page 29, original page 25C] Not transcribed

[Digital page 30, original page 25D]

[Subtitle]The Fishing Boat Story

Shortly after the debacle of the escape from the beaches at the mouth of the River Foro, near Francovilla, early in October 1943 and whilst the S.A.S. were still in the district, but were not really serving much purpose so far as the escaping Prisoners of War were concerned, we found a fishing boat with its crew who were willing to sail us overnight from Francovilla to Barae. I can’t actually remember the date when this took place but I know that we arranged to meet the S.A.S. Squad at a little jetty near Francovilla after dark, where we were to board this fishing boat and sail to Barae. Again it was a bright moonlight night and the owner of the fishing boat, an Italian, said it would take him well into the morning to make Barae but that he would clear the two front lines whilst it was still dark. In due course the S.A.S. Squad and ourselves met at this jetty along with the crew of the fishing boat which I seem to remember was probably three people, the Italian owner and two others. The boat itself was open, it had no closed in decks, it had a mast and a sail and a large rudder at the stern. We climbed in and so did the S.A.S. about six or eight of them and we were arranged on seats around the side of the boat which pushed off to start its journey. The boat was very, very low in the water. In fact the waves were lapping over the gunnells. No-one seemed very happy about the situation because it was drastically overloaded and the skipper himself said that he could not take so many people, it would be too dangerous and that some of us would have to go ashore. He said he thought that three would need to go ashore and by tills time the boat had drifted out from the jetty towards the deeper water. As soon as it was said that three had to go ashore it was quite obvious who the three were to be – the three escaped Prisoners of War – that is Gordon McFall, Guy Weymouth and myself, John Pennycook – and so we bade farewell and wished them a good voyage, jumped overboard into about six feet of water and made our way to the shore, soaking wet. When we pulled up on the beach we really were quite cold and decided quickly what we should do. Obviously to get back to our original farmyard which was possibly about two miles away, maybe more, we reckoned that it was too far to go and it was beginning by this time to get late at night, possibly about 11p.m. on a bright moonlight night, so we walked up the road passed two or three houses, turned left up a lane into the woods and wild country behind the houses, climbed a short hill, probably about half a mile in total from the beach, and we found a straw hut in which we thought we could spend the night. Looking inside the hut there was not much in it, hut nearby there was a haystack with plenty of straw which we immediately pulled to pieces, pushed into the hut, took off our clothes which were wet, hung them where we could outside the hut to dry them when the sun came up in the morning, got into the hut, buried ourselves naked amongst the straw and, believe you me, it was warm and we had a good night’s sleep. When we woke in the morning the sun was up, it was quite warm, our clothes were drying and drying quickly and as soon as they were fit to put on we dressed and made our way back to our original start-out point, where we thought we could get something to eat. We had no food with us at all. In due course we reached back to the farm where we had been staying and made contact with the farmer, told him of the disaster of the night and settled in to think what we were going to do for our next effort.

[Digital page 31, original page 25E]

Later on, at the beginning of January, after we had reached the Allied Lines and were on our way home, we arrived in Phillipville in Tunisia. In Phillipville were stationed the second S.A.S. and after we had booked into a transit camp as we were required to do we went along the road to see them to see if any of our friends were there. In fact they were all there and they were delighted to see us. They told us that the fishing boat had successfully sailed down the Adriatic and that they had landed near Barae early the following morning. Weren’t we jealous because that was probably the best part of eight weeks previously perhaps more. No perhaps nearer ten or twelve weeks previously. We sure were jealous. However, they entertained us in the officers mess, gave us a good dinner and laid on a fifteen hundredweight truck and drove us to Algeres overnight. If they had not done that we would have had to get the train from the transit camp the following morning and I think it would take about three days to get to Algeres. As it was the truck took us through Consantine, where we stopped at a British Guard Post and had a cup of coffee. It was very cold at Constantine and there were several inches of snow lying on the ground. However, the following morning we were down in Algeres and booked into the transit camp there from which, about a month later, we sailed for the U.K. That is the end of “The Fishing Boat Story”.