Summary of Peter Lewis

This gripping account reads like an adventure story, telling of the escape of a number of allied servicemen facilitated by courageous townspeople in the area of Modena. Apart from the stories of the allied servicemen, we read of the courageous efforts of many named Italian helpers. The reader is offered a fascinating insight into the partisan organisation in the town of Modena which assisted around 250 allied ex-PoWs to escape. They carried out their activities at great risk to themselves and we hear of arrest, torture and even of the execution of Italian helpers.

The documents include a speech by Michael Nathanson (son of the escaper Leslie Nathanson) which celebrates the Città dei Ragazzi, a place of shelter and support for boys of Modena, strongly supported by British donors in gratitude for Italian assistance given during the war.

The allied escapers included in this account are: Peter Lewis, Anthony Snell, Leslie Nathanson (Nat), Terry Muirhead, Ted Paul, Ernest Taylor, J.W. (Jock) Wright), G.P. Blitz, A. Holdridge, John Jeffries, Thomas Roworth and Robert Wilson.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

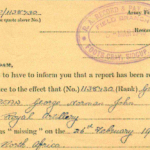

[digital page 1]

[Handwritten notes by Keith Killby]

Major Peter Lewis, M.C

5 copies of ‘Everybody’s with a title on escape of many PoWs in Modena and network. After the war they helped ‘Città dei Ragazzi’ in memory of priest tortured and killed by Nazis.

Sent in by the son of ‘Nat’ – Leslie Nathanson, who escaped with help of railway at Modena and Modena Network.

[digital page 2]

La Citta dei Ragazzi

In the A.R. for 1998 we report how Major Peter Lewis had, together with Tony Snell (‘The Man who would not die’ in Birkhill’s ‘Escape or Die’) had jumped from a hospital train. In spite of their wounds, they hid up until a small boy appeared in their hay loft saying ‘Tonight you will be taken to a place of safety’. They were fortunate to have been found by the Modena ‘Network’! That small but courageous organisation had begun when some Italian rail workers watched as half a dozen PoWs, independently, had taken advantage of relieving nature when their train stopped at the goods yards of Modena to hide in the undergrowth. Among them was Leslie Nathanson. The railway men got them quickly into civilian clothes and smuggled them in to Modena walking with the POWs carrying a red flag or the hammer to tap the rails. After some weeks it became dangerous in Modena with so many POWs and slowly, they were mostly guided north and into Switzerland. Most of them got away, some were recaptured but far worse some of their helpers were tortured and killed, including a young priest Don Elio Monari.

‘Nat’ as Lt. Leslie Nathanson was known, was among the most active of the many who were helped in Modena to return soon after the war and in 1953 to open the second house in the ‘Città dei Ragazzi’ opened in Modena to provide a home and a meeting place for the many boys in that city without a home or facilities for sport. ‘La Città dei Ragazzi’, still active today, had been greatly expanded through the financial support of so many PoWS , including General Carton di Wiart and Gen O’Connor and even the British Government. Those many who supported the initiative of ‘Nat’, as Nathanson was known, and Peter Lewis, though like all PoWs trying to rebuild their lives, were the first, after the Allied Screening Commission to record their great gratitude to the Italians. In the case of Nathanson, that expression of gratitude has extended to today, for his son Michael, like his father a solicitor in a leading London firm, was on the San Martino Trail with his son and raised a prodigious fine figure in sponsorship for the benefit of the Trust. Naturally the Trust is now seeking suitable candidates for Bursaries for the youth of Modena.

[digital page 3]

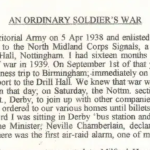

[Unidentified newspaper cutting titled “Pensioner recalls wartime heroism”]

[Photograph with caption] RELIVING THE PAST: Major Peter Lewis, of Northwood, looks at a poster celebrating the 50th anniversary of the idea of forming a place for boys to meet in the Italian town of Modena to repay wartime kindness.

Memories of kindness in the face of conflict were rekindled for retired Major Peter Lewis, 79, of Northwood, when he made a return trip to Italy.

On page nine, he explains why he will never forget the people who protected him after he escaped from a German prison train during the second world war.

[digital page 4]

Discorso di M Nathanson per le celebrazioni della Città dei Ragazzi il 5.10.97

Il grande privilegio di essere qui oggi è dovuto in gran parte a un evento straordinario che è avvenuto 54 anni fa, nel settembre 1943. Un soldato inglese che era stato catturato in Nord Africa veniva transportato su un treno tedesco con molti altri prigionieri verso Ia Germania. Quel soldato era mio Padre. La domenica mattina del 12 settembre 1943 il treno stazionava fuori della stazione di Modena. Mio padre lasciò il treno per un bisogno fisico e riuscì in un momento in cui Ia guardia si era distratta a saltare in un fossa da cui non poteva essere visto dal treno. Qualche minuto dopo veniva portato via da Joris Franciosi per venire affidato alla protezione di Mario Lugli, Don Mario, Arturo Anderlini e altre persone di Modena che, con rischio personale enorme, davano rifugio ed poi riuscivano a portare mio padre in Svizzera, attraverso Milano. Nelle sette settimane che mio Padre ha passato a Modena è stato trattato con grande gentilezza e ospitalità, enorme coraggio e aveva Ia gioia di gustare il Lambrusco per Ia prima volta. Peter Lewis, che era un altro dei soldati inglesi scappato attraverso Modena, è pure qui oggi e rappresenta quel gruppo di persone, che purtroppo va diminuendo, che devono ringraziare i coraggiosi cittadini di Modena per aver salvato le loro vite.

II 27 Settembre 1953 mio Padre ritornò a Modena con altri che erano stati aiutati dai coraggiosi cittadini di Modena per onorare Ia memoria di Don Elio Monari e il coraggio di Don Mario e molti altri. Con l’aiuto di donazioni del Governo Britannico e del popolo britannico che si erano cosi commossi a seguito degli eventi che erano accaduti a Modena, fondi venivano raccolti per aiutare a pagare Ia costruzione di uno degli edifici della Città.

Lord Mancroft, che parlò in quell’occasione a nome del Governo Britannico, concluse il suo discorso in questa modo: “II mio messaggio di speranza è che il Club voluto nato dell’amicizia e della buona voluntà Anglo-ltaliana, possa rafforzare nel cuore di questi giovani quei germi di

[digital page 5]

amore e carità che formano Ia via della vita cristiana. Quella sarebbe stata Ia speranza di Don Elio Monari che ha sacrificato Ia sua propria vita per quei principi, aiutando i prigionieri di guerra alleati Ia cui memoria onoriamo oggi”. Questa speranza è stata senza dubbio tradotta in realtà dalle grande visione e forza di Don Mario e di tutti quelli che hanno Iavorato senza posa con lui.

Quale risultato delle esperienze di mio Padre, Ia mia famiglia ha passato molto tempo in Italia e oltre ad essere un avvocato che lavora molto con I’Italia, sono anche Segretario Onorario della Camera di Commercia Britannica per I’Italia a Londra. In questa veste sono molto lieto di offrire un piccolo contributo della Camera di Commercia Britannica alla Città dei Ragazzi. Anche il Consulato Britannico a Milano ha offerto un altro contributo.

Quello che mi rimane da dire per Peter Lewis, Margaret McEwen, le suore Annunciata e Anna, me stesso e quelli che dall’Inghilterra sono stati coinvolti nella Città dei Ragazzi, ma che purtroppo non sono con noi oggi – è quanta ispirazione abbiamo tratto dal coraggio del popolo di Modena e dalla forza e visione di Don Mario e di tutti quelli che hanno Iavorato con lui. Noi tutti auguriamo tanta fortuna alla Città dei Ragazzi, per gli anni futuri.

[digital page 6]

[Photocopied front page of a publication by Roberto Vaccari]

La Città dei Ragazzi

40 Anni di Vita (1947-1987)

[digital page 7]

PRESENTAZIONE

Quando nel 1939 Don Mario Rocchi venne Cappellano a Saliceta S. Giuliano, dopo essere stato ordinato Sacerdote un anno prima, ed avere svolto la sua prima esperienza a Montombraro, noi ragazzi della Parrocchia capimmo che quello era un prete che ci andava bene, innazitutto perché giocava con noi a pallone in quel vecchio e stretto cortile che finiva col pollaio a cui teneva tanto la sorella del nostro Parrocco e poi perché quei suoi intensi ci dimostravano un grande affetto e nei contempo ci preoccupavano perché esternavano un desiderio ed una volontà di non lasciarci in pace.

Era un pescatore nato e un formatore formadibile di coscienza e ce ne saremmo accorti ‘a nostre spese’.

Saliceta a quei tempi era una Parrocchia rurale e la Ghirlandina non illuminata, era nascosta alla nostra vista dagli alberi e dalle viti che arrivarano fino alle porte di S. Faustino, era quindi tutta Parrochia tranquilla è piuttosto pigra ma quei giovane prete, porto aria nuova, nuove attività, nuovi ideali, nuovo amore.

Le sue attenzioni erano rivolte ai giovani ed ai bambini; eravamo alla vigilia della nostra triste entrata in guerra, la si sentiva nell’aria e lui guardava avanti, voleva proteggere, voleva preventire quello che sarebbe avvenuto poi, la guerra e il dopoguerra.

Nacque il nostro ‘Oratorio’ con i suoi gruppi, le sue classi catechistiche, con la formazione dei giovani e delle

[digital page 8]

giovani a curare i bambini, specialmente nelle giornate domenicali e festive.

E la nostra, con lui, fu una splendida esperienza, incontrammo il Signore e da allora non lo lasciammo più.

Don Elio Manari alcuni anni dopo lo trovò lì, una domenica, che arbitrava una partita di calcio non più ne cortile confinante col pollaio, ma in un quasi vero campo di calcio, ricavato nel vigneto del Prevosto che lui era riuscito a scroccargli.

Don Elio… caro, magnifico prete di Dio, sii benedetto.’

Ebbene Don Elio, che da tempo vedeva ed amava Don Mario, Ianciò l’idea: anche a Modena doveva nascere un Oratorio, in periferia, per i ragazzi della guerra e del dopoguerra.

E nacque così Ia “Città dei Ragazzi” in mezzo ai paduli, dove ancora vi scorrevano i fossi di acqua sorgiva, bella chiara, non inquinata ma che, in seguito, avrebbe dato qualche problema ai fini edilizi e sportivi.

La spinta di Don Elio iniziò Ia realizzazione del sogno che Don Mario aveva sempre conservato nel suo grande cuore.

Una casa, due case, tre case, Ia piscina. i campi sportivi, Ia scuola, i ragazzi, tanti ragazzi, i giovani. tanti giovani sono passati per Ia “Cidierre”.

I ragazzi di un tempo sono diventati nonni, oggi seguono i nipoti sempre alla “Città”, perché Ia C.d.R. vive ancora, ha lasciato un segno e continuerà nella sua opera educatrice affinchè i ragazzi di oggi siano gli uomini di domani, più buoni, più fratelli, più cristiani.

L’idea del 40° di questo libro è nata dai più vecchi allo scopo di fare festa assieme ai giovani al ‘grande Vecchio’ che ancora è l’anima della ‘Città dei Ragazzi’ di Modena che fondò quando era uno splendido giovane prete a cui il Signore ha voluto e vuole un gran bene.

E anche noi!

Giovanni Vincenzi

[digital page 9]

[Photograph with caption] Ritorno di Leslie Nathanson con Mario Lugli e Joris Franciosi su luogo (la stazione di Modena) dove Joris salvò Nathanson nel 1943.

al lago d’Iseo e alle montagne del bresciano. Nel 1951 avviene la disastrosa alluvione del Polesine e la Città dei Ragazzi e invitata ad ospitare 40 raggazzi delle famiglie di profughi di quella zona. Questi sono accolti con fraterna sollecitudine e saranno ospitati presso la Città dei Ragazzi per circa un anno.

Intanto il numero dei ragazzi che frequentano cresce e lo spazio per accoglierli adeguatamente non basta più. Si sente sempre più presseante l’esigenza di nuovi locali, ma la mancanza di mezzi non permette di costruirne altri.

Gli amici inglesi: la seconda casa

Il Signore, sempre provvido verso coloro che hanno Fede in Lui, viene incontro in maniera insospettata. Nel 1951, alcuni ex prigionieri inglesi del campo di concentramento di Via Nonantolana (TODT), liberati ad opera dei modenesi

[digital page 10]

[Photograph with caption] L’Arcivescovo Mons. Boccoleri taglia il nastro per l’inaugurazione della seconda casa.

[digital page 11]

[Photograph with caption] 1953. Un momento della cerimonia di augurazione della seconda casa.

L’8 settembre 1943, vennero a Modena per rivedere gli amici che, a suo tempo, si erano interessati alla loro salvezza, e in particolare per ricambiare il bene che avevano qui ricevuto. L’incontro avvenne tra Leslie Nathanson, Peter Lewis, Tomas Roworth, Mario Lugli, Mons. Domenico Grandi ed altri. Fu deciso così di costruire una seconda palazzina alla Città dei Ragazzi da dedicarsi alla memoria di Don Elio Monari. che tanto aveva fatto per la !oro salvezza, e per la salvezza di tanti loro connazionali, nel periodo in cui erano perseguitati dai nazisti.

In Inghilterra fu indetta una sottoscrizione patrocinata dal settimanale illustrato “Every Body’s”, che usci raccontando in quattro numeri successivi Ia storia dei connazionali

[digital page 12]

[Photograph with caption]: Il Prefetto di Modena, al microfono con a fianco l’On. Alessandro Coppi, all’inaugurazione della second casa

salvati dai modenesi e Ia storia della Città dei Ragazzi di Modena. A Londra, poi, venne indetta, e curata dall’Avvocato Leslie Nathanson, una raccolta di offerte, che venne estesa anche a tutto il Commonwealth britannico, fino alla Nuova Zelanda; con tale iniziativa,·si raccolsero circa undici milioni. Mancavano però ancora tre milioni e mezzo per coprire totalmente Ia spesa della costruzione; lì offri Ia regina Elisabetta per interessamento di Lord Mancroft, personaggio che fu poi inviato a Modena alla cerimonia di inaugurazione della palazzina il 27 settembre ’53 in rappresentanza della regina, e recante anche un messaggio del generale Eisenhower.

Si stabilava così un saldo rapporto di amicizia tra Ia Città

[digital page 13]

[Photograph with caption] Lord Mancroft, con Ia moglie e altri amici inglesi, all’inaugurazione della scconda casa.

dei Ragazzi e gli amici inglesi, i quali misero in contatto Don Mario con L’International Help for Children fondata da John Barclay e Miss Margaret MacEwen sotto Ia presidenza del sindaco di Londra. Questa istituzione benefica offri a 25 ragazzi della C.d.R. le vacanze gratuite per 45 giorni da trascorrere nelle città di Manchester e di Sunderland. Vacanze meravigliose che si sono ripetute per ben 27 anni consecutivi in diverse città dell’Inghilterra, e che ha dato ai ragazzi che vi hanno partecipato una esperienza indimenticabile e costruttiva sul piano educativo. E non è tutto. In quegli anni l’Avvocato Leslie Nathanson, con alcuni amici, creava a Londra un Trust of Charity, una fondazione di beneficienza denominata “Amici inglesi della Città dei Ragazzi di Modena”, facendovi così continuare ad arrivare sussidi pre-

[digital page 14]

ziosi; sussidi che hanno accompagnato per molti anni Don Mario e i suoi Collaboratori nel lavori di costruzione della Città della Ragazzi.

La terza casa. Attività sportive

Intanto la vita della “Città cresceva e si pensò di costruire una terza palazzina (secondo il progetto originale) per ospitare anche il Centro di Formazione Professionale (aparto nel frattempo), che comprendeva corsi di addestramento per saldatori e falegnami, seguiti poi da corsi per elettricisti e per radiotecnici; corsi tutti funzionanti, finanziati dal Ministero del Lavoro.

Col crescere del numero dei ragazzi, a un certo punto si senti il bisogno di organizzare l’attivitàsportiva, che è una.

[Photograph with caption] Da destra: John Barclay, Laura Randihieri, Miss Margaret MacEwen, Mario Lugli e Don Mario Rocchi in occasione di una visita degli amici inglesi all C.d.R.

[digital page 15]

[Title page of Everybody’s magazine, 3 May 1951]

[digital page 16]

They helped us to Escape – 1

ENCOUNTER IN MODENA

This is the first of four articles telling a story of Italy after the armistice, when German and Fascist forces were trying to hold up the advancing Allied armies. It is also the story of a group of Italian townspeople who valued the cause of freedom more than their own lives. When the opportunity came for them to help escaped British prisoners of war, they did so without hesitation. Some of them were executed, others were tortured and others disappeared; yet their fight was not in vain. In four months, these brave men and women of Modena helped no less than two hundred and fifty escaped British prisoners of war to reach the safety of Switzerland, Rome, or the Partisan forces in the mountains.

ENCOUNTER IN MODENA

By Major Peter Lewis M.C.

who lived in Modena as a ‘guest’ of the Underground for two months and has just recently returned from a visit to the town where he met again some of the people who had comprised the Modena Underground Movement.

The interior of the cattle truck smelled strongly of horse manure and of very fresh, overpowering human sweat. What little light there was came from the two small grille windows and through the semi-opened sliding doors.

The heat was oppressive and the majority of the thirty or so British officers, packed tightly against each other, wore only pants and vest or slacks and shirt. Outside a youthful guard of the S.S Adolf Hitler Division lounged against a buffer with a tommy-gun held menacingly in his hand.

It was a Sunday morning – September 12, 1943 – a few days after Italy had signed an armistice with the allies. The long train of cattle trucks, which had been standing in the sidings of Modena station all night, was scheduled to leave for Germany that day. Captain Thomas Roworth of the Royal Engineers stretched his legs as best he could in the confined space and then looked at his watch. It was 7 a.m. What a miserable and uncomfortable night it had been. Surely the Germans would allow the men in the prison train some exercise now that it was light. As if in answer to his musing, the doors of the next truck slid back and he heard a voice ask in halting German whether it was permitted to cross the lines to the side of the train to satisfy the needs of nature.

The answer came at once – a guttural ‘ja’ – and looking out of the truck Roworth saw a brother officer pick his way across several sets of lines, a roll of toilet paper in one hand. Roworth looked beyond to where a group of Italian railway employees sat on benches outside a concrete building. Next to the building was a signal box and then a small allotment with a large rabbit hutch. What a magnificent chance to escape, he thought to himself. If I can get inside or under that hutch, I can stay there until the train moves off.

By this time the S.S. guards along the length of the whole train were allowing one man at a time per truck to walk across to the side of the tracks. This went on for twenty minutes or so and then the guards relaxed their discipline and three or four prisoners at a time from each truck were allowed out.

Seized his chance

At a few minutes after eight o’clock Roworth jumped down from his truck and with his roll of toilet paper held prominently so that the German guards could see it, he sauntered across to the grass verge where he stood for a few moments looking up and down the tracks. A quick glance told him that the attention of the German guards had been diverted by the sound of shooting which came from the direction of the main station buildings, some five hundred yards away. Roworth seized his chance and darted into the allotment where he threw himself under the rabbit hutch. He was more than relieved to find that the hutch faced away from the railway and towards a road running parallel to the tracks. So long as no German guards came into the allotment, he was safe. Meanwhile several other British officers had escaped from the train and Roworth was soon joined by Captain Robert Wilson of the Royal Artillery who also manoeuvred himself into position in the small hiding place under the hutch.

Aroused Some Suspicion

Another escaper was a Gunner Lieutenant, popularly known as ‘Nat’. Ten minutes after Roworth had left the train, Nat jumped down from the truck next but one and walked innocently towards the garden in front of the railway building. However, he aroused more suspicion than Roworth had done and it was some minutes before the S.S. guard was satisfied that Nat’s mission was a legitimate one. When he was finally convinced, he turned away to continue his patrol, and the Englishman ran round to the back of the building where he threw himself full length in the long grass. Almost at once he heard a voice. It was Wilson en route to the rabbit hutch, telling him to move as he could be seen. Nat crawled into a less conspicuous position where for the next half an hour he proceeded to festoon himself with various flowers, shrubbery and vegetables from the allotment. Confident that he was fairly well concealed both from the railway and the road he was a little shocked when he heard an urgent ‘Pssst!’ Looking in the direction of the road he saw a pleasant type of well-covered Italian who beckoned urgently. Nat was afraid that the crew of a German self-propelled gun on the road would become suspicious and he made a pleading gesture to the man to go away. To the Englishman’s relief the Italian, with a happy, knowing smile, went on his way.

Meanwhile, in the Modena Sports Stadium on the far side of the road an urgent conference was taking place between the Director of the Stadium, Gaston Ronchi, and several of his friends. From the enormous, rather vulgar observation tower of the swimming pool, they had watched the train since early morning and had actually seen the escape of Roworth, Wilson, Nat and two others. They had sent the restaurant manager, Joris Franciosi, to patrol the road, and it was he who had beckoned to Nat. Now they were planning how to get the escapers away and into the swimming baths.

For three hours they watched the train and for three hours, the five men who had escaped stayed hidden and prayed that the train would move off. But it stayed where it was and the S.S. guards continued to patrol along the crowded cattle trucks. To the men in hiding, it was an agony of suspense.

Provided with Clothes

At 1 p.m. Germiniano Malaguti, a Modena signalman came on duty and was told by the stationmaster to go to his signal box and to stay there so that he would be out of danger if the Germans fired along the train to keep the prisoners quiet.

When Malaguti and the remainder of the relief signalmen reached the box – only a few yards from where Roworth and Wilson were hiding – and waiting until the coast was clear, Malaguti was told that several British prisoners were in the vicinity. Without any hesitation Malaguti decided to help the men escape. He walked down the steps to where an officer named Wiltshire was hiding and, waiting until the coast was clear, bundled Wiltshire into the large railway building next to the signal box. Here Wiltshire quickly changed his clothes for an Italian civilian outfit which included a short-sleeved, open necked shirt and a magnificent, sombrero-type Italian hat. Malaguti then pressed a bundle of clothing into Wiltshire’s hand and then pointed out of the window to where Nat was lying. The next thing Nat knew was Wiltshire standing over him and throwing down the bundle of clothes. “Get into those, Nat and go through that window.” He pointed towards the railway building. “They will look after you inside.”

[digital page 17]

[Photograph with caption]: Malaguti on the steps of his signal box, and Roworth (right). Roworth was paying a return visit to Modena with the author and for this photograph dressed in the jacket and cap that he wore during his escape in 1943.

The bundle contained a pair of yellow denim trousers and a long black overall coat, torn in several places and well-marked with oil and grease. Nat lay on his back and quickly dressed himself. Then he got to his feet, walked round behind the hut and climbed through the window. Through the open doorway he could see the prison train, not more than 25 yards away. The sliding doors of many of the cattle trucks had been locked and all the prisoners were on board. He looked at his watch. It was 15 minutes after 1 p.m. He had been in the garden five hours.

In the hut, Nat mingled with seven or eight Italian railwaymen and tried to look like one of them. He was scared. It was quite obvious to the Italians that Nat was an escaped prisoner and any one of them could have called the S.S guard, only a few yards away.

Brilliant Idea

A quarter of an hour passed and then, to Nat’s relief, Malaguti walked into the hut, having taken Wiltshire to a place of safety. From the recesses of his voluminous overalls, he produced a high, peaked cap similar to those worn by railwaymen all over the world. Nat tried it on. The fit was perfect, and now he felt fully clothed.

However, Malaguti was not satisfied with the disguise, and produced one more trump. With a little smile of self-satisfaction, he put a red flag in Nat’s hand. The Italian reasoned that if the English prisoner was going to be an Italian railwayman then he must have a red flag. It was as simple as that, but to Nat it seemed a brilliant touch.

A few moments later Malaguti took his charge by the arm and together they walked past the S.S. men outside the front of the hut and, keeping parallel with the prison train, they followed another line which eventually branched off towards the road. The two men climbed over a small fence and suddenly Nat felt an irresistible urge to run across the road and through a side entrance to the sports stadium. In fact, he would have done so had not Malaguti grasped him by the arm. Then Joris Franciosi seemed to appear from nowhere and he too slipped his arm through the Englishman’s. “Piano, piano, tutto va bene.” (Take it easy, everything will be all right) he said.

The trio crossed the road without undue haste while a hundred yards or so away the crew of the German self-propelled gun glanced idly in their direction. The two Italians led Nat into the Sports Stadium to where Gaston Ronchi was waiting. He shook the Englishman by the band, then led the way to the office buildings and up a flight of stairs. He stopped before a door and pressed the bell three times. The door was quickly opened and Nat found himself in the entrance ball of a small apartment.

A Tough Egg

Malaguti asked the Englishman to take off his coat and denim trousers, and when he had done so the ltalian stuffed them under his coat and, letting himself quietly out of the flat, left Nat with his host. Ronchi led him into a well-furnished living-room where two men and a woman were sipping wine. One of them was Wiltshire and the other was obviously British. Wiltshire introduced him as Ted Paul, an Australian, and added: “He got off the other end of the train earlier on this morning.”

Paul had walked to the side of the tracks in the same way as the other escapers. He waited until the German guard was looking the other way and then somersaulted backwards over a pile of sleepers. He then raced across the station yard to a high wall. Some of the prisoners on the train had seen this daring escape and they watched from the trucks with bated breath as Paul leaped at the wall. His fingers clutched the top and with a tremendous effort he raised himself inch by inch until he was able to drop into the road beyond.

A few seconds later the watchers on the train saw him standing there, looking first right then left like a hunted animal. They saw an elderly Italian riding towards Paul and gasped as the Australian gripped· the handle-bars of the man’s bicycle. They expected the Italian to give the alarm, but instead be got off his bicycle and warmly shook hands with Paul, then walked with him along the road towards the Sports Stadium.

Paul was in a cold sweat. for he still had on a khaki shirt and blue Air Force trousers, and he could see that within a few minutes they would draw level with the crew of the German gun on the road. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, Joris had darted from the side entrance to the stadium and dragged Paul inside. The Italian with the bicycle waved, mounted his machine and went off as though nothing had happened.

Nat looked at Paul and thought how easy his own escape had been; he wondered where Paul had found the strength to scale the wall. The Australian was certainly a tough egg.

Replied In English

Meanwhile Malaguti had returned to the railway. He walked over to where Roworth and Wilson were hiding and tossed the bundle of clothing to Roworth. It took the Englishman a few minutes to massage his cramped limbs and then be dressed himself in the clothes which Nat had worn, and walked out of the allotment with Malaguti. Roworth had added a wheel-tapping hammer to his disguise, and as he and the Italian walked along the prison train, he gave the wheels a resounding tap every ten yards or so.

The sliding doors of several of the trucks bad been pushed open to let in some fresh air, and as Roworth walked past one truck an Army lieutenant leaned out and asked for water. Before he could stop himself, Roworth had said: “Sorry, old boy. Haven’t got a drop.” The man in the truck could not believe his ears and there was a look of incredulous amazement on his face. Roworth wanted to laugh, but dared not do so.

The two men walked away from the prison train and crossed the road to the side entrance of the stadium where Joris was waiting, and Roworth was led alongside the swimming pool, where by this time a party of Germans were splashing about, and into the main building. Within ten minutes he and the others were joined by Wilson, who had come by the same route from the rabbit hutch.

As the four men were drying themselves after a welcome shower bath. Gaston told Nat that the Germans had only left the building at five o’clock that morning.

The Italian then led the Englishmen up into the tower. and from one of the windows, they were able to Jook down on the prison train. It was 2.30 p.m. and as the escaped prisoners watched they saw the train start to move. “Poor devils,” said Wiltshire. “Another year in the ‘bag’”.

German Visitors

A few minutes afterwards, Lt. Terry Muirhead of the Essex Regiment arrived, having been ‘collected’ by Malaguti. There were now six British escapers in the apartment. each wondering how they were all going to get out and what sort of disguises they would wear. Ronchi, it seemed, had already thought of this. At intervals Italians entered carrying a parcel or a suitcase of clothes, and soon each of the six men were dressed as an Italian. Muirhead and Wilson, with their fair hair, still looked like Englishmen, and they were given large, stetson-type hats.

Then, as Ronchi’s wife – Pina – came out of the kitchen with an appetising dish of pasta, there were two sharp knocks on the outer door. Outlined against the frosted part of the upper part of the door were two men. One of the Italian women, Claudia, called out that she was coming and asked what the visitors wanted. As she walked out of the kitchen the answer came in Italian, spoken badly and gutturally, and the Englishmen knew they had German visitors. Ronchi told the Italians to carry on a loud conversation and then leaned across to Nat, and whispered urgently: If the Germans come in here, you and your friends must go on eating as though nothing is wrong. Pretend to be Italians having a late Sunday lunch. I will do all the talking.”

Nat looked across at Roworth and then at the other escapers. Was this to be the end of their new-found liberty? For two minutes that seemed like two hours there was the mumble of voices and then the suspense was

[Photograph with caption]: Reunion dinner at Easter with the Lugli family. (Left to right) Mario’s sister Ada, Peter Lewis, Mario, Mario’s wife and his mother. The womenfolk lived in the house throughout the operations of the Underground group.

[digital page 18]

[Photograph with caption]: Tom Roworth greets Malaguti at the entrance to the rabbit hutch where he had spent those memorable five hours. With them is Mario Lugli

ENCOUNTER IN MODENA (continued)

broken. Claudia came back into the room. “It’s all right,” she said. They were a couple of German soldiers who wanted a bathe. I’ve given them towels and costumes and they’re quite happy now.” The Englishmen turned to their lunch – the first decent meal they had eaten for years. Their appetite was not what it had been before the arrival of the Germans, but nevertheless it was a fine meal. There was the excellent pasta, and salad with a dressing that was just right, and rabbits which had been cooked over an open fire so that their sides were golden-brown. The bread was white and free from the hay, straw and sawdust which had been a feature of the daily ration of 125 grammes in the camp. The local red wine of Modena, Lambrusco, was good and plentiful, whilst the gateau had a filling of real cream.

Looked Tough

The six men had just finished their meal when two Italians walked into the room. One of them – the taller – gave the impression of being a prosperous merchant. The other was smaller with thin, pointed features, but nevertheless a pleasant face.

Both of them Iooked tough, each in his own individual way. The taller was introduced as Mario Lugli and the other as Luciano Vezzani. Lugli came straight to the point, and it was obvious that no time had been lost in arranging accommodation in Modena for the English escapers. For it was out of the question for the six men to stay in the swimming baths which were used by the Germans daily.

“I can take two guests in my house.” said Lugli. “I am ready to leave at once, but if you prefer, I can wait until dark. But in these times, I think it is less suspicious to go whilst it is still daylight.” Vezzani said that he could accommodate another two for a few days. Joris offered to take the remaining two.

It was finally decided that the Englishmen should be conducted out of the grounds while it was still light. Wilson and Roworth went first with Mario Lugli and Armando, his brother, and as they were about to leave, Pina gathered up her baby son and handed him to Wilson. Ronchi explained to Roworth: “Your friend is too blonde to be an Italian. You will have to pass the Germans in the pool on the way out and perhaps they will be suspicious. But if he carries Mario here, I am sure they will not suspect.”

So it turned out and Howorth and Wilson reached Mario Lugli’s house in Via Ganaceto without incident.

Arrived Safely

The others set out in their turn. Joris linked arms with Nat and Luciano with Muirhead. The four men walked through the streets of Modena with the two Italians talking volubly in the patois peculiar to the district, and Nat and Muirhead gesticulating just as volubly with their hands as they had so often seen their captors do in the various camps.

On the way they passed two guards of the Royal Carabinieri, who took no notice of the Englishmen. They crossed the main square, the Piazza Grande, almost brushing shoulders with several German soldiers, and then they turned into a narrow alleyway. Here, Joris and Nat turned into a small tenement house and the ltalian led the way up to the fourth floor.

By the time the door was opened Muirhead and Luciano had arrived, and all four were admitted to the apartment of Loris’s sister and brother-in-law.

That night the six Englishmen slept safely in three different houses in Modena, and an organisation was born which within the short space of four months was to clothe, feed, hide, and finally pass on to the safety of the mountains, Switzerland or Rome no less than 250 British escaped prisoners of war.

Next week’s article tells how four men created the Modena Underground, and of how the organisation hid new arrivals in the town, and then arranged for Roworth and Wilson to be escorted to Rome by three priests.

[digital page 19]

[Magazine title page] Everybody’s May 12, 1951

[digital page 20]

[Photograph with caption] The entrance to Modena Prison Camp as it is today, badly damaged by Allied bombing. It was from here that two South Africans, Britz and Holdridge, escaped. After living in the country for two weeks they were picked up by the Underground and brought into town.

They helped us to Escape -2

CHALLENGED BY S.S.MEN

By Major PETER LEWIS, M.C.

In last week’s instalment, the author described how British officers escaped from a P.O.W. train in Italy shortly after the Italian Armistice and how brave Italian townsfolk sheltered them. This week he explains how priests guided two of the men to safety and how he himself was helped by men of the Modena Underground Movement.

That evening in Via Ganaceto, 80 – an address that was to become well known to many escaped prisoners in Modena – Roworth and Wilson dined with the Lugli family.

As they sat around the table after an excellent meal, drinking coffee and smoking a last cigarette before turning in for the night. Roworth asked Mario why he had helped the escapers. “It is really very simple,” replied the Italian. “In the first place I do not like the Germans por the Fascists. In fact, I have never been a member of the Fascist Party. In the second place I was well treated by your soldiers in Abyssinia.”

Mario explained how he emigrated in 1935 in the town of Harrar in Abyssinia where he set up his business of importing wine and cheeses from Italy. Unlike many of the settlers, who only rented their land, he bought his piece of land. “When your army came in March, 1941,” said Mario “I stayed on – it was, after all, my own land and my own home.”

“… It Was My Duty”

At this point Anna, his wife, took up the story. “Eventually Mario was sent to a camp – it was in July, 1942. He was ill and it was necessary for his health that he was sent home to Italy. Your English medical officers were very kind and a certificate was issued. Eight months ago – in January – we came back.”

Mario looked across at Wilson and Roworth. “There is a very big difference between the Germans and the English as conquerors,” he said. “Your officers were always ‘gentile’ (kind) but the Germans here in Italy… what pigs they have been.”

From the time of his return in January, 1943, he had carried on his business, taking no interest in politics, and then had come the armistice between the Allies and Italy. “I knew then,” said Mario, “that it was my duty to do all I could against the Germans and Fascists. You two are the first I have helped.”

For two weeks Roworth and Wilson lived in Via Ganaceto and after having been cooped up in various P.O.W camps it was like living in another world – even though the frontiers did not extend beyond the apartment. Except at mealtimes, they were confined to a large, old-fashioned room with a magnificent four-poster bed.

This seclusion was deemed advisable since many people used to visit the house during the day and Mario only told a select few about his ‘guests’. The two men passed the long days by improving their shaky Italian with the help of Mario and his sister, Ada, and by looking out of the shattered windows at the people passing by in the street below.

The town itself was fairly quiet. At the time of the train escape there were very few Germans actually stationed in Modena although there were a number of transport columns parked in the vicinity.

Mario explained that the Germans had seized control of the key centres, such as the post office, railway station and town hall. Apart from this they were not exercising any direct control over the population. Most of the Royal Carabinieri had changed into civilian clothes when the armistice was announced and gone home whilst the Fascists in the town, and there were not many, had taken off their black shirts and were quietly in hiding awaiting developments.

Sensational Rumours

Modena was alive with unfounded rumours, the more sensational ones reporting British landings well to the north, at Trieste and Spezia.

Howorth and Wilson arranged with Mario that a daily bulletin, taken by them from the B.B.C. on their hosts’ wireless, should be delivered to the other escapers to keep them informed of the situation. Nat and Muirhead were settling down in their new home, whilst Paul and Wiltshire had been moved to a large country estate where they were living in a spacious, though rambling house, owned by Signora Ardlani.

It was now eight or nine days since the escape from the train and Mario received information from friends of his that other British prisoners were arriving in the vicinity of Modena, some of whom had escaped from Modena prison camp at the time of the armistice whilst others had escaped from trains farther to the north.

The Italian realised from the discussions he had with Roworth and Wilson, that it would be many months before the Allies reached Modena, and that an organisation would have to be built up in the town to look alter the escapers if they were not to be re-captured by the Germans or Fascists.

He contacted two priests, Don Monari and Don Richeldi, and Arturo Anderlini who kept a shop in Modena for the sale of cameras and optical goods.

The four men discussed the situation and decided that they would have to work fast.

A number of families in and on the outskirts of Modena would have to be listed as willing to hide escapers, and from other families they would require food and clothing. A doctor would be needed in case of illness or in case any future escapers arrived who had been wounded.

The Organisation would also require a photographer to take pictures for the forged identity documents which would have to be prepared. They would also want the services of men or women with access to the German and Fascist H.Q. and to the Italian Municipal Offices. so that when identity cards could be obtained it would be possible to have them franked with the necessary stamps.

Couriers would also be needed as links in the Organisation, and escorts and guides to take the escaped prisoners south to Rome or north to Switzerland when the time came. The four men realised that the safest escort would be a priest, and three more priests – Don Taccoli, Don Rocchi and Don Grandi – gave their services willingly.

Don Monari and Don Richeldi then visited houses in the town and obtained clothing and promises of food. Afterwards the two priests, together with Lugli and Anderlini, took different sectors of the town and arranged for accommodation. By the end of the third week in September no fewer than 35 British escapers, including the six original escapers from the prison train, were living in Modena – the welcome guests of Italian families.

On the Run

Modena was only one of many towns and villages behind the German lines where the people helped their ex-enemies. After the Armistice it is estimated that no fewer than 20,000 prisoners of war, freed by the Italians. were on the run. After week – or months in some cases – 6,000 reached Switzerland and many more got through to the Allied lines in the south, largely because of the invaluable help given them by Italian civilians.

The Modena Underground was typical of many, organised by four men who had no previous experience of such work and built around a framework of ordinary townsfolk. The task which now faced the Underground was how to get the escapers south to the Allied armies or north to Switzerland.

Making Preparations

The problem was solved by Roworth and Wilson who were guinea-pigs for the first trip south. Since their arrival in Via Ganaceto the two officers had spent hours every day poring over maps and discussing ways and means of getting away from Modena.

One afternoon Don Monari came to see them and Roworth asked the priest whether it was possible to get to Rome. He felt that if they could stay in Rome for a while, they could plan a further trip south to the Allied lines. Don Monari replied that he himself would reconnoitre the possibilities, and next day travelled to Rome where he was able to arrange accommodation for the two officers. Don Monari was confident that if the Englishmen had a good disguise, they could reach Rome safely.

They Were Disguised

He reported back to Mario and there was an immediate conference to discuss disguises. At one stage it was suggested that the two men should dress up as nuns. Wilson opposed this suggestion partly because it would mean shaving off the moustache, he had trained so well in camp but mainly because the journey to Rome would take 36 hours and it would be necessary to shave at least four times between Modena and Rome.

He pointed out that nuns do not normally occupy train lavatories for long periods in order to shave and in any case their faces would become raw from the continual scraping and would give the game away. It was finally decided that Wilson and Roworth should be disguised as travelling merchants. Three of the priests would accompany them.

Don Monari, through his many contacts, obtained commerce permits

**********************

BOYS’ TOWN APPEAL FUND

In Modena a Boys’ Town to accommodate 1,200 is being built (as described in “Everybody’s”, April 28). One of the houses there is to be dedicated to the memory of Don Elio Monari, the young priest who was executed for the help he gave British escapers. It is hoped that those who were helped by the Italians – and also their friends and relatives – will subscribe to the Appeal sponsored by Field Marshal Alexander for £7,000 to build the Don Monari house. It will be a symbol of gratitude to all Italians who assisted the Allied cause.

[digital page 21]

for the two officers (it was not possible at this early stage in the life of the Organisation to obtain identity cards) and then Arturo Anderlini came to Via Ganaceto and took passport photographs which were afterwards pasted on to the permits. Anderlini also gave the two men dark glasses, the first two pairs of well over a hundred that he was to provide during the next few months.

The clothes for the journey came from the well-stocked shop of friendly, jovial Alvaro Fornieri in the Via Emilia, and Roworth and Wilson were ready for the journey.

Two More Escapers

On September 28th they said goodbye to Mario’s mother and sister and to Anna his wife and left with Mario for the station. It was 11 a.m. and after Mario had bought the tickets, Roworth and Wilson walked through on to the station platform where they met the three priests – Don Monari, Don Rocchi, and Don Taccoli.

The train was late but Mario waited with the five travellers, and when it eventually left Modena he stood on the platform and waved until it was out of sight. Then he walked slowly back to Via Ganaceto, a little sad because he had made good friends of the two officers, especially with Roworth. At the house he found a message waiting for him that two South African majors, who had escaped from Modena Camp at the time of the Armistice, were in the country and waiting to come into the town. Mario wasted no time and within 24 hours the two South Africans – G.P. Britz and A. Holdridge – were safely housed in the room which had been vacated by Roworth and Wilson

Spoke In German

Meanwhile the travellers had not had an uneventful journey to Rome. At Chiusi – a hundred miles from Rome – the train was stopped and boarded by a German search party, looking for weapons in the luggage. Soon after the carriage had slowed to a halt the doors of the compartment were pushed back and a German S.S. man stood in the entrance. Wilson had his eyes closed, pretending to be asleep, and the German pushed himself into the compartment where he addressed Roworth. He pointed to the suitcases on the rack above Roworth’s head. His question was almost a bark. “What is in those cases?”

Roworth could see that the priests were more than alarmed and he had a premonition that if he spoke in Italian the German would not be satisfied and would ask a lot more awkward questions. To this day Roworth does not know what made him do it but looking up he replied in German, “Machine guns.” The S.S. man stared at him intently for a moment or two and then his face broke into a smile. He muttered something in his own language – probably the equivalent of ‘wise guy, eh?’, hunched his shoulders and backed out of the compartment.

After a delay of almost an hour the train continued on its way and early in the morning after a 40-hour journey arrived in Rome.

The five travellers walked across the city and through St. Peter’s Square to an apartment building where they were lodged safely. Next day the priests returned to Modena a little more confident than when the venture had first been suggested, but a little shaken by the incident at Chiusi.

Jumped from a Train

In Modena the Underground was by this time functioning perfectly. Mario had even gone to the extent of enrolling an employee at the Post Office whose job it was to open letters written by citizens to either the German or Fascist H.Q. and to check that no one harbouring escapers was being given away. Escapers were being picked up and helped almost every day in the country districts by contacts of Mario, Anderlini or the priests.

Together with Fl/Lt. Anthony Snell D.S.O. I was one of those fortunate people who were brought into the town. Tony Snell and I were en route for Germany on September 26th when we jumped from a train under cover of darkness in the vicinity of Mantova. For seven days we walked in the fields, heading south and being given shelter by Italian families every night.

It was when we arrived in the village of Fabrico, at the house of Silvio Terzi and his brothers, that the Modena Underground picked us up. A leading resident Dr. Ottavio Corgini, knew that we had arrived and next day he travelled to Modena where he called on a teacher of languages, Miss Gina Giorgi, who had an English mother, and asked if she knew of anyone who could help. “The two officers can stay there another day,” said Corgini, but it is a small village, and I am afraid the Fascists will find out if they remain any longer.”

Our lnstructions

Miss Giorgi immediately contacted Mario Lugli, for she had on several occasions visited houses where he had boarded his escapers, to act as an interpreter. Mario met Corgini at once and the two men arranged that we should be brought to Modena without delay. Corgini returned to Fabrico that evening and came to see us right away.

“Tomorrow morning you will go to the town of Modena by train,” he said, “with Pietro as a guide. You will be taken to the railway station by two of the men here, and your tickets will be bought for you and handed to you outside the station. You must then walk through on to the platform on the far side. When the train comes in, do not get into a carriage but into a cattle truck. There are no corridors connecting the trucks and the Germans cannot question your identity whilst you are on the train.”

The Italian lit a cigarette and continued. “You must not attempt to converse with Pietro, although he will be in the truck with you. When you reach Modena walk outside the station after you have given up your tickets and you will see me bending down on the far side of the road, doing up my shoelace. You will both light cigarettes to signify that you have seen me and then you must follow me. But on no account try to catch me up or speak to me. Pietro will leave you at the station as he is not allowed to see where I take you.”

Wonderful News

Giorgini peered at both of us and then addressed Tony to whom he had done most of the talking in French.

“You have understood?”

Tony nodded, “Yes, perfectly.”

“Well then, that is all I can do for you. Good luck to you both and until tomorrow, au revoir.”

This was wonderful news indeed, and ·and next morning two guides took us on the crossbars of their bicycles through the countryside and to the railway station where Pietro was waiting. As we cycled through Rollo, a small village, I felt that everyone was staring at me and that the people in the main street knew we were English. It was a most uncomfortable feeling but we reached the railway station without incident and our guides went in and bought the tickets for us.

We passed the ticket collector and walked on to the platform. The Modena train was 10 minutes late and I had time to take stock of our position. I noticed that it would be rather tricky if we did have to make a break, for the platform was fenced off with high palings.

Madness To Turn Back

At last the train pulled in and Pietro climbed into a cattle truck. Tony and I followed and we were a little disturbed to find two German soldiers also in the truck. However, it would have been madness to tum back and we moved into the shadows where we took a lively interest in the morning paper, which neither of us understood. After an uneventful journey we reached Modena and followed the two Germans out of the truck and past the ticket barrier into the square in front of the station.

We saw Corgini bend down and do up his shoelaces; we lighted cigarettes. The Italian moved off and we followed him. We must have walked round the town several times for we passed the station on two occasions but eventually Corgini led us into Via Ganaceto and it was not long before we were were welcomed by Mario Lugli. “After you have had a coffee,” he said, “you will meet two South African majors who are living here with me.”

The coffee did us a world of good and then we met Britz and Holdridge who told us that Roworth and Wilson had gone to Rome. Britz explained that we were to wait in Modena until it was safe to move south and that later that morning we were being taken to a furnished flat.

Photograph: A recent Picture of Major T. Roworth, D.S.O, M.B.E., with Don Rocchi and Don Grandi, with spectacles, two of the priests who did so much work for the Modena Underground. Don Rocchi accompanied Roworth on the Rome escape route in 1943. He is now the senior executive officer of Boys’Town.

Photograph: The author, on his recent visit to Modena, greets Mario Lugli and his wife at the entrance to Via Ganaceto 80 – the house where so many plans were made and escapes to freedom organised. The room to the left above the door is where Mario hid his guests!

[digital page 20]

[Title page for Everybody’s Magazine 19 May 1951]

[digital page 23]

They helped us to Escape – 3

WE TAKE ON NEW IDENTITIES

By Major Peter Lewis, M.C.

Last week, the author told how he and his friend reached the comparative safety provided by the Modena Underground Movement. In this article he describes life in Modena and the preparations for their escape into Switzerland.

Just before lunch Marie took us to our hideout. We walked through Modena, passing groups of German soldiers. After ten minutes or so we arrived at Via Canalchiaro 33, and climbed two flights of stairs to a small door where Marie tapped three times, a signal we came to know well.

It was opened by a cheerful youngster – Peppino – who took us through to the lounge. This was luxury indeed. There was a wireless set, English playing cards, novels and magazines. Then Peppino showed us where the food was kept in the kitchen and how to work the cooking stove. I nudged Tony. “Look, there’s a packet of tea. It must have cost them the earth.”

Watched The People

A few minutes-later we met Quinto Reggiani, the man who had put his home at our disposal and moved into the country with his wife and small daughter. He had equipped the flat with almost military precision. In the bathroom were shaving things, toothbrushes and other toilet requisites. Laid out in the bedroom were underclothes, shirts, socks and shoes.

After Quinto and Peppino had left, we sat by the windows in the lounge and watched the people in the street below, for the room overlooked one of the main streets of Modena. After an hour of viewing the ever-changing scene we allowed ourselves the luxury of a cup of tea and then sat with our ears pressed to the radio, and the volume at its lowest, whilst we listened to the B.B.C. news from London.

After a day or two we came to know many people in the town. Regularly at three o’clock every afternoon a little man cleaned out the tramlines and every morning at 11 o’clock an attractive but rather haggard blonde hurried along on the far side of the street. The little man we called George and the blonde was nicknamed Rosie.

There were many others, including an old man with a magnificent beard who used to frequent the Trattoria (inn) opposite. A few yards from the Trattoria was a jeweller’s shop, very popular with the German troops stationed in Modena. We used to watch them park their vehicles below our window and walk into the shop.

Quinto and Peppino visited us morning and evening whilst Mario came to use every other day. He had at this time 25 escapers in his section. After we had been on our own for just over a week two other escaped prisoners arrived. One was a private in the Cameron Highlanders – J.W. Wright – and the other a Royal Marine, Ernest Taylor. His hair was blonde and he did not look at all like an Italian so it was decided to dye it black. We spent two hours in the kitchen one afternoon dyeing it, section by section, the required shade. A few days late Private John Jeffries of the Sherwood Foresters arrived. There were now five of us in the flat.

Unpleasant Experience

It was whilst we were living in Via Canalchiaro that my teeth gave me a lot of trouble and Mario arranged for me to visit Dr. Giuseppi Grossi. He was a charming man and a good friend of the British. I used to enjoy my visits to his surgery because they took me out of the confined space of the flat for an hour or two.

However, I had rather an unpleasant experience one day crossing the Piazza Grande, the main square. I was sent sprawling on the cobblestones by a party of Germans, who had just climbed down from an open lorry, because I did not get out of their way quickly enough. I lay partly stunned whilst they swaggered away. Then Peppino, who was escorting me, helped me to my feet and took me back to the flat.

By the middle of October, the Germans had taken over complete control of the town and distributed leaflets offering 18,000 lire, equivalent to £45, for information leading to the recapture of escaped Allied war prisoners. Article 1 of the Ministerial Decree of October 9th, 1943, threatened with the death penalty anyone found harbouring or helping is. Planes flew low over Modena dropping leaflets in thousands, and manifestos were fixed on walls throughout the town.

On October 26th, six weeks or so after the escape from the train, Signora Ardlani’s house in the country was raided by Fascist Militia and plain clothes police. The Signora, her daughter, two pro-British Italian officers and an Austrian girl companion were arrested; in the outbuildings the Fascists discovered Paul and Wiltshire, together with a South African who had been billeted there by Mario. They were all bundled into a lorry, driven to Fascist H Q. in Modena, and transferred to another truck which would take them to German H.Q.·

Tommy-Gun Fire

The eight prisoners climbed dejectedly into the truck followed by three guards, armed with revolvers and tommy-guns. A few minutes later, as they were going through a quiet part of the town, the Australian, Paul, with a magnificent leap, jumped clean over the tailboard when the driver slowed to negotiate a sharp corner. He had timed it expertly. As he stumbled to his feet and ran for his life, the corner shielded him from the furious bursts of tommy-gun fire which swept the cobblestones behind him.

The sound of shooting had sent everyone indoors and Paul had the street to himself as he raced along and turned another corner at the far end. Panting, he staggered into a cycle repair shop and through into a back parlour where he found the proprietor. “Inglese prigioniere,” he gasped painfully, “Scappato”. And then in English “Can you help me?”

The Italian was only too pleased to assist, and Paul asked to be taken to the station. The man agreed and even lent him a bicycle for the short trip. At the station Paul thanked his new friend and, waiting until the Italian was out of sight, walked along the road beside the railway until he reached the Sports Stadium. Here he scaled the wall, dropped down inside and was soon ringing the bell of Gaston Ronchi’s flat. Pina answered the door. She stared at Paul in amazement as he lurched in and slumped down in a chair. For a minute or two he sat with his head in his hands and his eyes closed. Then he told Pina what had happened.

Emergency Plan

She immediately got in touch with Gaston who had gone out and he in turn contacted Mario Lugli and Joris Franciosi. They decided to put an emergency plan into operation, for Signora Ardlani knew both Mario and Joris, and whilst she would not willingly betray them, the Germans and Fascists had ways and means of making a woman talk. lt was therefore decided to move Britz and Holdridge from Mario’s house and Nat and Muirhead from Joris’ house that night.

Just after nine o’clock in a deserted, unlighted street – not more than a hundred yards from the entrance to Modena’s San Eufemia Prison -Nat, Muirhead, Britz, Holdridge and Paul, together with their Italian guides had been marshalled by Mario to await the arrival of our young friend Peppino.

Drunken Germans

It was hardly the time or place to ‘Talk shop’, but Paul insisted on describing his adventures, and his audience were engrossed in the story when a door was flung open, fifty yards or so away, and a shaft of light disclosed several vague forms stumbling out into the night. The escapers and the Italians eased back quietly into the shadows and watched fearfully as 12 to 15 Germans lurched by in varying degrees of drunkenness.

The last German to pass – muttering and cursing to himself – lurched heavily as he drew level with Nat and barged into the Englishman. He grasped the lapels of Nat’s coat as he leaned forward and his breath reeked of alcohol. Nat muttered a polite “Permesso” and turned away. The German with an unsteady movement of his hand which might or might not have been an attempted punch, staggered off to catch up with his drunken friends.

Drawing: “I was sent sprawling on the cobblestones by a party of Germans … because I did not get out of their way quickly enough.”

Photograph: This picture, taken a few weeks ago, shows the view from the lounge window of Via Canalchiaro 33, the flat where Peter Lewis and Tony Snell were hidden. The Trattoria (inn) is on the left and the jeweller’s shop, much frequented by the Germans, is on extreme right. Trolley buses replaced the ancient trams which ran in 1943.

[digital page 24]

WE TAKE ON NEW IDENTITIES

A few minutes afterwards, and with only ten minutes to go before the curfew, Peppino arrived. When the five escapers had been pointed out to him he set off with Paul, followed by the two South Africans and then Nat and Muirhead, The other Italians went off quickly in the opposite direction.

When Peppino rang the bell of our flat you can imagine Tony’s surprise when he opened the door and the five men walked in. For-we knew nothing of what had happened. Terry Muirhead could not resist a jest. He glanced round: “We only want one more and we can field an all-England eleven at the Stadium.” Jock Wright looked up quickly. “The devil you can! Don’t forget I’m Scotch.”

We Said Goodbye

The Underground had lost no time in finding other accommodation in the town and next day the two South Africans left us followed by Wright and Taylor, then Nat and Muirhead. The following morning Tony, John and I said goodbye to Quinto. It was a relief to leave his flat because we all felt that he had taken more than his fair share of risks. His face showed unmistakable signs of the great responsibility be had shouldered and the good-natured Italian was a sick man.

We were taken to an apartment in Via Ganaceto – not far from Mario’s house – occupied by Signora Martinelli, a charming middle-aged schoolteacher, her daughter Anna – a dark, attractive brunette – and her son, Amadeo.

Held For Questioning

Meanwhile, the Germans had sent Wiltshire and the South African away from Modena whilst Signora Ardlani and her daughter were held for questioning. The signora denied all knowledge of the three escapers and explained to her captors that they had come to her for food, which she had given them and then told them to go away. “Instead,” she said, ” these men hid in one of the barns or outhouses on my estate, so it is not my fault that they did not move on. I certainly did not know they were there.”

The Germans kept the Signora in gaol for eight or nine days and then released her provisionally. They may have believed her story but it is far more likely that they hoped she would lead them to the men at the head of the Modena Underground. The raid on the house had confirmed. their suspicions that there was an organisation of some size in the town.

Meanwhile the Underground, after ticking over slowly for a few days following the raid, was now working at full pressure again. Joris Franciosi took the train north to Milan and then continued to Domodossola near the Swiss-Italian border. Here he contacted a band of smugglers and arranged that for £30 per person Nat and Muirhead would be taken over the mountains into Switzerland, followed by other pairs of escapers from Modena.

Full of Confidence

The Rome escape route was still open and several parties had gone down there since the original trip by Roworth and Wilson, but our Italian friends felt that if we could get to Switzerland there was a better chance of our reaching England.

On a Monday morning, almost seven weeks to the day since the escape from the train, Nat and Muirhead, escorted by Joris and another Italian, caught the Milan train. Their five-hour journey was uneventful and they arrived full of confidence and in good spirits. However, they still had to pass the ticket barrier and it was here that disaster almost overtook them. There was a check of identity cards and neither Nat nor Muirhead had one.

They stood there, wedged together in a milling throng of people pushing and shoving to get through the barrier Then, from the crowd, came an angry ltalian voice: “What the devil are these people messing us about for? Damned identity cards. We’re sick of these controls.”

This furious outburst had the desired effect. The crowd pushed and shoved to such an extent that the barrier was knocked aside and Nat and Muirhead were swept through, and safely past the Fascist guards, on a tidal wave of disgruntled and excited Italians.

Nightmare Journey

They spent the night in Milan and at eight o’clock next morning caught a train for Domodossola where they were handed over to the organisation which was going to get them over the mountains.· After a nightmare journey the two Englishmen were successful in reaching Switzerland, and when the smugglers arrived back in Domodossola with signed receipts, indicating that Nat and Muirhead were safe, Joris and his friend were able to return triumphantly to Modena to report the success of Swiss Trip No. 1.

After a delay of three weeks, due to the fact that the smuggler bands all along the frontier were working at full pressure to deal with the heavy traffic in refugees as well as Allied escapers, the two South Africans, Britz and Holdridge, went with Franciosi to Domodossola and crossed safely into Switzerland by the same route. However, this time Franciosi did not return to Modena. He had been captured by the Germans soon after handing over the South Africans to the smugglers.

Went lnto Hiding

It transpired that Franciosi was tried and sentenced to transportation (which would have meant the gas chambers of Buchenwald), but he escaped from the train taking him and thousands of other unfortunate Italians to Germany, and by devious routes returned to Modena where he went into hiding until the liberation.

Meanwhile, Toby, John and I had settled down happily with the Martinelli family. The principal room of the apartment was used as a schoolroom, and consequently we were confined to our sleeping quarters – a curious type of windowless room leading off from the hall – every morning whilst the classes were in session. The entrance to the room was behind a cupboard standing in the hall. We went to bed at about 11 p.m. and once the cupboard had been put in position, there we stayed until 2 p.m. the following day when we emerged for lunch. For 15 hours out of every 24, we were cooped up in this tiny bedroom.

One day the son-decided that it would be safe for us to go to the cinema. It would relieve the boredom and as he knew the box-office girl it would be a simple matter for us to get inside.

Frontier Smugglers

At eight o’clock we were ready to leave the flat, but Amadeo was delayed and did not arrive home until two hours later. We had good cause to thank Amadeo’s chief who had kept him working late. Next day he told us that just after the main film the lights had been switched on to reveal German soldiers standing at the entrances. They took all the young men of military age and within an hour they were packed like animals in cattle trucks, en route for Germany.

Meanwhile the Underground had found another route into Switzerland. Don Monari, the young priest, went via Milan to the H.Q. of a band of smugglers in the small frontier village of Tirano, where he was able· to make satisfactory arrangements regarding payments and receipts. A day or two afterwards Mario told us that we were to be the guinea pigs for the new escape route. “You must have exercise,” he said. “Your friends had eaten so well and were so much out of condition that they only just succeeded in getting over the mountains.”

After Mario had gone, we gave some thought to the problem of how to exercise ourselves, and it was Amadeo who eventually found the solution. He suggested that we should go out in the evenings with Anna, and one of. her friends. “It will arouse less suspicion if you are with a pretty girl,” he said. He was quite right. When we saw Germans or Fascists coming towards us, we used to stop in the entrance to an apartment building or a shop doorway and the patrols were completely fooled.

It was Anna who obtained Fascist identity cards for us. She worked as a clerk in the-Town Hall and one evening she produced two cards triumphantly from her handbag. We filled in the particulars right away and I became Pietro Lotti, a merchant of Modena. It was now only necessary to make us both look a little more like ltalians in preparation for the journey and Amadeo took us to a barber’s shop almost directly underneath the flat, where we had our hair cut and moustaches trimmed. The barber, an old and trusted friend of Amadeo, had attended to us after closing time and as we were preparing to leave, Amadeo took him by the arm. “Now don’t forget. Not a word about these two. They’re British escapers.” The barber smiled back. “It’s all right,” he said, “I’ve got two myself at home.”

The next step was to obtain passport photographs for the cards and Mario called for us just after dark one evening and walked with us to the photographer’s studio.

Everything Arranged

Next day the photographs arrived. Each card had to be franked with the German imprint stamp and Anna· volunteered for this dangerous task. The franking machine was in a room in the Town Hall, which was left unoccupied only on very rare occasions.

Twice Anna tried unsuccessfully to get into the room. The third time she was lucky. The room was left empty for no longer than three minutes but during that time Anna removed the cover from the machine, franked each card, then replaced the cover and returned to her own office.

We were now ready for our attempt to reach Switzerland, and two days later Mario walked into our room where we were still lying in bed. His face was beaming. “Mr. Snell… Mr. Lewis,” he said, ”Tonight you go to. Switzerland. Everything has been arranged and you will have guides and money. My brothers will take you to Milan.”

Next week the final article describes the adventures of the author and his companion when they climbed the Alps into Switzerland, and of the tragic events which overtook the Modena Underground after they had left.

Photograph: The Fascist identity card used by Flight-Lieut. Snell. It describes the holder as Mario Rossi, a student of Modena, and the German imprint stamp can just be seen on the right-hand side of the photograph. The author had a similar card.

Photograph: Anna Martinelli. She obtained Fascist identity cards from the Town Hall of Modena and, when completed with passport photographs, took them back and franked them with the German imprint stamp.

[digital page 25]

[Title page for Everybody’s Magazine 26 May 1951]

[digital page 26]

[Photograph with caption] The Piazza Grande, Modena, where the Fascists shot 20 hostages in July 1944, including a boy of 15. It was a month of terror with Fascist murder squads roaming the town.

They helped us to Escape – 4

Over the Frontier to Freedom

At last, the vital day came – success or failure, freedom or a prison camp depended now on a hair’s breadth of chance. In his final article the author tells how – after many adventures – the escapers reached Switzerland.

By Major Peter Lewis, M.C.

That night, after saying goodbye to John who was next on the list for ‘evacuation’ to Switzerland, Tony and I thanked the Martinelli family and walked to the station with Mario. Here, he handed us over to his brothers Armando and Aldo. After trying to express our gratitude in the few words of ltalian we had learned, our guides took us into the station.

When the Milan train arrived it was like trying to board a London ‘tube’ during the rush hour. In almost total darkness we squeezed in with our two guides. When Tony put his suitcase up on the rack he dislodged another one which fell on an Italian sleeping below. There was an immediate uproar and we both looked innocent as Armando took the blame and apologised profusely.

That was not the only incident. We had both lighted cigarettes and after taking a puff Tony dropped his hand to his side; there was a smell of burning. He had touched somebody’s coat which was now smouldering. This time Aldo took the blame, and for the second time that night we were grateful to the R.A.F. for making a blackout of all trains necessary.

Hours of Waiting

When we arrived in Milan it was impossible to leave the station because of the curfew. We had three hours to wait for the train which would take us on the first stage of our journey to the frontier. We sat there feeling most uncomfortable because there were a large number of Germans about. Just before dawn Armando handed us over, together with a hundred pounds in notes, to a Milan businessman who guided us to our train.

Half an hour after we left Milan a ticket collector demanded to see all tickets. I showed him mine and he said something in Italian which I did not understand. He spoke again and, by this time, the other occupants were staring at me. I pointed to a scar on the side of my face, a recently-healed war wound, and made some curious mumbling noises with my mouth. Then my guide seized control of the situation. “My friend cannot answer,” he said, “He is deaf and dumb as a result of the war. Is his ticket not in order?”

The collector explained that I had given up the wrong half of the ticket. Very cleverly our guide pretended to tell me the situation in deaf-and-dumb language and, as I had now realised what was wrong, I produced the other half. The rest of the journey was uneventful and we left the train at a tiny wayside station and followed our guide along a country road to an isolated bouse.

Early that evening a boy arrived to guide us farther along the valley. It was an eerie walk through woods and by a river, but we arrived eventually at a small mountain village where we spent the night. Next morning we walked to the railway where we boarded a train which took us to within about three miles of the Swiss-Italian frontier and walked across country to the tiny smugglers’ village of Tirano.

Started The Climb

Our guide led us to the house of the two men who were to take us into Switzerland. That evening when we sat warming ourselves in front of a roaring fire, there was a knock on the door, and an Italian in Fascist uniform walked in. Tony and I both jumped to our feet. He walked over and shook hands. “Don’t worry, I am working for the Underground. It is my job to ensure that the German frontier patrol will not be in your sector when you cross over tonight.”

We had quite a party in that cottage and drank far too much wine. At two o’clock, after a few hours’ sleep, we started the climb and pressed on up a mountain path, which was almost perpendicular in places. After we had been going for just on two hours, I began to feel groggy. Every time we turned a corner, I hoped that there would be a flat stretch, but there was always another path going straight up as long as the one we had just climbed.

After climbing for three and a half hours we came to a small mountain stream, and we all lay down on its bank and drank deeply. By now I was beginning to feel the effect of our party. It seemed as though the wine had gone to my legs and it was as much as I could do to lift one foot after the other. We climbed on until snow made an appearance on the mountainside. Our halts for rest were more frequent but our guides urged us on, saying that it would soon be daybreak.

At eight o’clock in the morning there was still some way to go and it was already light. The guides were worried and jumpy; so were we. By now Tony was also feeling groggy and every ten minutes or so he or I would flop down, press our faces in the snow and eat a mouthful which seemed to refresh us.

The mountain path was very stony and as we were only wearing thin Italian shoes, the stones bit right through the soles. Tony was practically walking on his socks.