Summary

Geoffrey S Stavert (RA) was captured in Sidi Nsir, Tunisia in February 1943. He was originally held in the “cage” camp at Bizerta. Then transferred to Campo 66, near Capua, Italy, where, due to overcrowding, he was housed with the French POWs. He was then transferred to Campo 49, Fontanellato, near Parma. He remained there until September 1943 when the Italians surrendered, and due to the impending arrival of the Germans, the entire camp fled. The 500+ escapees split into smaller groups. Stavert and 3 others accepted an offer to stay with a large Italian family in Fontanellato.

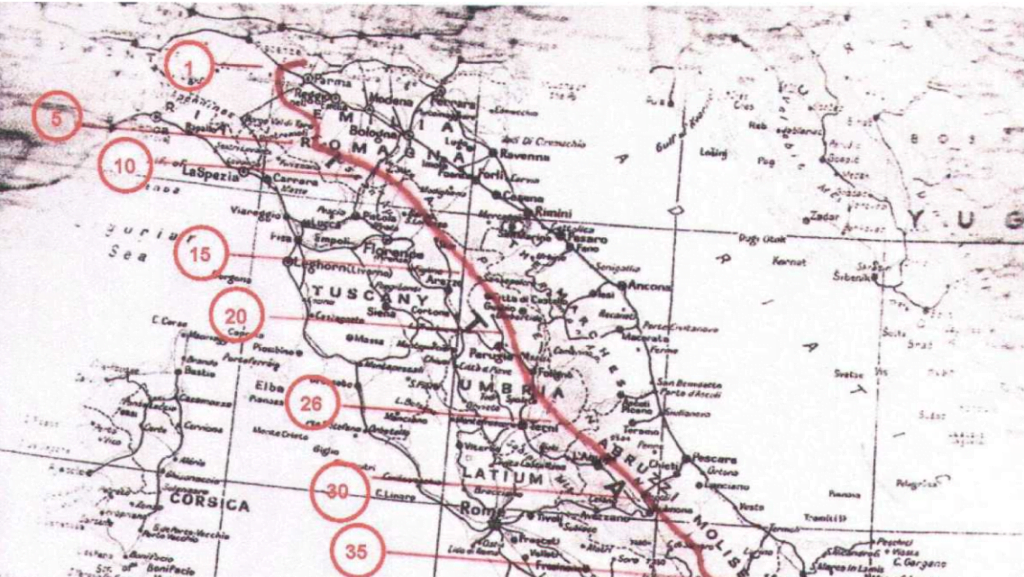

After a week, they were advised to move on. The Germans were closing in which risked both their safety and that of their hosts. They headed east towards the Italian coast, aiming to walk up to 20 miles per day. Along the way they hoped the locals would provide them with food and drink, and at the end of the day they hoped to find a friendly farmer who could put them up in his barn overnight. After 6 days doing this they reached the town of Altedo, where they were greeted like returning heroes.

[Digital pages 1-20 refer to the 4 prisoners in this story as Geoffrey Stavert, Harold Magee, Peter Gardner and Ray Pipe. Within digital pages 21-170, the last 2 prisoners are referred to as Peter Kibble and Ray Piper.]

Part 1 of 2. Read part 2 here.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital page 1]

FOUR FROM FORTY-NINE

Geoffrey Stavert

| Chapter | Folio | Digital pages | |

| 1. | Sidi Nsir, 26 February 1943 | 1 – 15 | 22 – 36 |

| 2. | For You The War is Over | 16 – 36 | 37 – 57 |

| 3. | The French Hut at Campo 49 [66?] | 37 – 55 | 58 – 76 |

| 4. | The Last Days of Campo 49 | 56 – 84 | 77 – 105 |

| 5. | Another Four in the Family | 85 – 108 | 106 – 129 |

| 6. | “Before You Go” | 109 – 119 | 130 – 140 |

| 7. | Gentlemen of the Road | 120 – 149 | 141 – 170 |

[Digital page 2]

[Handwritten summary of all chapters, which are in both Part 1 and Part 2.]

Geoff RN. All told with touches of dry humour and reflects well the language + behaviour of some officers.

Commander G. S. Stavert, A slow march through occupied Italy

– Magee, Stavert, Peter Gardener, Pipe

– from Fontanellato. From N. Africa Feb 1943

– Germans stopped Allies at Green Hill, Bald Hill + Loughton Hill

Chapter 1. Excellent description of Artillery overrun by tanks in N. Africa.

Chapter 2. They march[?] back. The Germans go for a wounded man who had dropped out. They had to stand in pouring rain for the [1 word unclear]. A very mixed German convoy passed – but all stopped [2 words illegible] when 9 Hurricanes appeared. 5 officers are picked up. Green [2 words unclear]. Moved to Bizerta Cage – with the Italians for a week.

Chapter 3. Taken to Naples and to Capua PG 66. G.S. with Magee put in with French + welcomed to an orderly society – compared to British Officers huts. The French played cards all day, 4 Guards officers from the L. R. Decent group from the French end who also continued good [1 word unclear].

Chapter 4. May 1943 Fontanellato. In cattle wagons. They enjoy the march from the station. Good on characterisation + dialogue.

72 De Bergh takes over + beards etc disappear and the camp became organised.

Tchaikovsky’s 5th Symphony was broken by cries of Armistice. Orders to stay put and endless speculation. 9th de Bergh announcers main Officers camp at Bologna taken by Germans. Prepare for evacuation.

What + what not to pack. Three blasts on the bugle + they marched out.

Chapter 4. After 2 days they begin to disperse. Magee + GS are told there 2 others waiting to go a bundle of old clothes to choose from + 2 girls waiting to take them home.

[Chapter 5.] Usual huge family eating in kitchen + a barn for them to sleep in.

Chapter 6. Padrone arrives coldly – as an old Etonian he offers help but warns of danger but [we] are invited to lunch. They welcomed at a side door – as they were junior officers – by a colleague from F. who orders ?servant to bring more food. Next day he had gone – on his way south to meet 8th Army. Young Padrone urges them to leave which annoys the contadini.

Chapter 7. A tearful farewell. The paths are obvious + easy. They try out their Italian on a man digging – another POW trying to be a local.

They walk through Sorbolo.

Chapter 8. Hospitality + food was hard to come by. Carpi. Meet 4 of 1,200 men in Carpi – who with many had dropped out when the Germans marched them off. The boy who had led them + the ORs produced a map + 100 cigarettes.

’39 + can time ? 7 canals had to be crossed. The hot flat landscape meant hard dull walking till evening. They were again in farmyards.

Another big canal ?basin there s/eastward journey but a cart takes them to Bridge in the middle of rice fields. They get given grapes, figs, apples and walnuts, then bread and guided on their walk from Alteda.

Chapter 8. They see and feel the bombing of Bologna. Grape harvest time and they are fed along the way where there were many refugees from the cities and many women with children who had not heard of their husbands for many months.

[Digital page 3]

Chapter 8. They left chits all the way. After more rivers the landscape changed and the surroundings poorer. A boy is sent to find them shelter.They follow him but is distraught when a group of men say ‘Mangiare si dormine no’. Germans had searched Bagnacavallo for POWs. They plodded on in the rain. Tempers get frayed. A man takes them to his 12 foot square earth floored room where his wife and one son are eating dry bread and grapes. He claimed an English Officer had shot the German attacking him. He opens a door and shows them his cows in their barn where they were welcome for the night. In a dark drizzle they set off. Sheltering in a farm house 3 POWs from a Working Camp near Verona walk in. Walking carelessly on a road a vehicle stops before they can hide. He speeds them away for many dangerous miles until ejecting them near the Savio river. With a phalanx of villagers organised by a boy they cross the bridge with a caribiniere frightened to take any action. Heartened they march on. A woman [1 word unclear] a loaf of bread from her basket, a man on a bicycle guides them to his home. Mattress and blankets were provided on the floor of their living room.

Chapter 9. With the sea 3 miles away in ? days. To Cesenatico for a boat – told to ask for Fifo. G.S. has to go as he spoke Italian. G.S. encounters Mrs Fifo and is blown backwards who wanted to know when he would be back – already away with one load. A family gives them lunch and a daughter takes over washing their clothes. They spend a jolly evening with a large family. Try Bellaria. Many attractive boats. They find young ex army officer on his boat. Nothing could persuade him to help in their escape. The 4 set off disconsolate, 2 farmers turn them away. But there is a cowshed – and early in morning G.S. is woken by a stray cow.

Chapter 10. They had, literally, crossed the Rubicon. They were among hills for the 1st time. Decided to make it by land. But it is a switchback journey they walk through the state of San Marino.

Food and entertainment in evening and bread and cheese in ham with luck.

G.S. enjoys too much of a sweet and seemingly harmless wine.

They crossed the Via Flaminia. They agreed 4 was too many but did not know how to split. Food supply was being erratic.

Rain and mud so slither on the hills with alternate over supply + under supply of food.

Chapter 11. In sight of Macerata a man lays on a food meal and tells them to avoid Sforzacosta – where there had been a POW camp. A lone worker sees them – a man of 30 – but hopping on a wooden leg roars a welcome to them and with his family they are 11 seated for a meal with the kids on the floor. Parachutists – Eng come in to get them out are definitely around. The sudden appearance of success overwhelms them. and next day they go on hopefully +first a [2 words unclear] and 5 other ranks who tell them it is off. Food and [2 words unclear] women would come each day from the village (2 smartly dressed in uniform and Partisan

[Digital page 4]

Chapter 11. At last they see + pass Macerata. Warned against Sforzacosta area so many POWs (from the camp there) still around.

Corridonia. Sunday all clean, shaved + in best clothes – but usually bare feet. Meet two well dressed in B. uniform who heard of the 4 of them. They confirm Capt Timothy parachuted in to help evacuate by sea. 2 intend to stay. Lunch was laid on for all – including some 70 Partisans with a large cache of arms, etc – but no guards. G.S. pleased 2 OR [Other Ranks] were not [two words illegible].

They go on with mixed euphoria and anti-climax is it all seems nearly over. They meet boy in Sunday best who tells them it is all off as Germans got on to the Civitanova Exit. They find half dozen cocky POWs who are well supplied with food + other creature comforts. They return to the pleasure of the large family.

Chapter 12. Excellent description of Fermo [Tenna?]valley which they traverse with determination. Well received at midday. Pass over Fermo [Tenna?]+ Monte Urano camp. Next day Ascoli Piceno became the next town to pass. Peter who had ankle trouble persistently. A man brought up the rear. An argument on which path to take. They had heard about parachutists. A young boy with excellent English shows them where the house where they are. The door opens, a well-armed British Officer greets them and says he was expecting them. 2nd SAS (Power). After much chatter plans are explained but not detail + offer of help – as officers not accepted or they were not in uniform. Sent on to help CSM Marshall in the Menocchio valley. Spend night in Aso valley. They leave at 6.30. Montefiore. The contadini are outwardly wary but know who they are + who they are looking for + point to a house. A huge figure with a Tommy gun opens the door + welcomes them.

Marshall however tactfully suggests 4 such dressed officers were best lying low. He finds them a house with a bed for the night – me on the floor.

Chapter 13. The couple are obviously uneasy. They find a big house with lots of people. Given minestrone but no room – refugees from bombing. They have to return with Peter obviously ill. Next day a JU 52 crashes very near. In 2 parties they seek new abodes + find a good house for all four, but with no walking time hangs. Allied Fighters are often to strafe German columns + visible on the coast road.

[Digital page 5]

Chapter 14. The sound of a vehicle wakens them to immediate exit with clothes pulled on. After 100 yards hidden they found the padrone with his pigs also hidden but one said he must have his boots – they were around his neck. Another billet must be found.

Burst of automatic fire. Is it CSM Marshall + his HQ. 2 set off for information + meet a variety of POWs + by chance Marshall. For he had shot a German. Germans had taken view of the men + found ?one extra but plan still on for some 200 [men] in the area on the Sunday. With nowhere to go – + nothing to do the 4 spend a difficult day + lapse into (artificial) discussion on religion. A 40 year old Staff Sergeant who had walked alone – on the roads from Bologna passes through.

Chapter 15. 24th Oct. They had ‘holed up’ in a rare uncultivated piece of land covered in gorse. Their last meal – cold pasta but all the valley seemed to know of the operation.

They begin the walk to the beach – no moon

They saw + heard German traffic on the coast road which together with the rail is squeezed tight beside the beach.

They arrive early on the beach + wait, cold [1 word illegible] Suddenly automatic + rifle fire. They cowered + thought that was the end of the rescue.

Slowly other groups + some SAS gather.

Start to signal. For 2 hours then a slight sound

A splash + a rubber boat. A variety of Naval + Army officers came in one of whom thinks is an Italian.

[Digital page 6]

Manuscript – [typewritten summary of chapters 4 – 15].

‘Four from Forty Nine – A Slow March through Occupied Italy.’ Good Maps By Geoffrey Stavert R.A. with H.A. Magee, Peter Gardner and Ray Pipe. All told with a touch of dry humour and with realistic dialogue.

When the Germans stopped the Allies at Green Hill, Bald Hill and Longstop Hill, G.S [Geoffrey Stavert] was captured in North Africa. Marched back and made to stand for the night in pouring rain. In Bizerta camp for a week and then taken via Naples to Capua PG 66 and put in with Magee in a hut with French POWs.

Chapter 4. May 1943 to Fontanellato. de Bergh [possibly Colonel Hugo de Burgh] takes over, beards are banned and order takes over. Tchaikovsky’s 5th Symphony is interrupted by cries of Armistizio. Hearing officer’s camp at Bologna taken over, de Bergh [possibly Colonel Hugo de Burgh] orders prepare for evacuation. GS [Geoffrey Stavert] and Magee are told there are clothes to change into and two girls waiting to take them and two others to their home.

Chapter 6. Padrone visits the farm – an old Etonian and invites them to lunch – via the side door of his mansion. They are welcomed by another Officer POW who orders lunch. Next day he moves on and the padrone urges them to follow. They try out their Italian on a man ‘pretending’ to dig – another POW. They meet four of ORs [other ranks] who dropped out when being marched, by the Germans from the Camp at Carpi. A boy brings them a very useful map and 100 cigarettes.

In marching east through the flat Lombardy plane they have to cross by various means, endless canals. At Alteda the local people almost line up with a variety of food to give them. (Where has this been recounted before?, KK) They see and feel the bombing of Bologna. They compete with refugees from the cities for accommodation. (They left chits with those who helped them.)

After more rivers the landscape changes and becomes poorer. A boy is sent to help find them shelter but the boy is most upset when many say ‘Mangiare si, dormire no.’. There had been many German searches. They meet 3 ORs [other ranks] from a work camp in Verona. Walking carelessly on a road a vehicle stops – but insists on giving them a lift for several hair-raising miles to near the Savio river. With a phalanx of villagers, organised by a small boy they cross the bridge and the carabiniere is frightened to take any action. A man on a bicycle guides them to his home and puts mattresses on the floor for them to sleep on.

Chapter 9. With the three miles to the sea they decide to go to Cesenatico for a boat and are told to ask for Fifo. SS [Staff Sergeant] with the best Italian gets the full blast of Mrs ‘Fifo’ who asks when Fifo will be back. A family takes them in and the daughter washes their clothes. They try for a boat at Bellaria and find many good ones and one very good one with the owner sunning himself on deck – an Italian ex-officer. His engine has been confiscated and he has no intention to help. (Where has this been incident and Fifo been read before?, KK) Turned away from two houses, they are shown a cowshed to sleep in. S.S. [Staff Sergeant] is woken by a stray cow!

They literally cross the Rubicon river and decide to make it by land but it is a switchback of hills. Pass San Marino. Bread and cheese they often find and of course grapes, but little more – except wine which sometimes impedes their progress! After crossing the via Flaminia going to Ancona they agree four is too many and agree to split – but how ? so don’t.

Chapter 11. In sight of Macerata a man tells them to avoid Sforzacosta – on the outskirts – as there was a POW Camp there and there are several POWs still around. A man working on his own and having a wooden leg gives them a huge welcome and takes them back to his family. 11 adults sit down to eat with the children eating on the floor. Parachutists seem to have definitely landed. The sudden approach of possible success almost overwhelms them after their rapid hard slog. The next day they meet five other ranks and a doubtful sergeant, and then another 2 – smartly dressed in uniform. But ‘it’ is off, the Germans having got wind of the evacuation plans. On Sunday all the contadini are washed and shaven and in their best clothes make their way to Church – in bare feet. A small boy in his Sunday best tells them ‘it is off’ because the Germans were on to the Civitanova exit plans. The six under a doubtful sergeant were well supplied with food and other creature comforts!

[Digital page 7]

‘Four from Forty Nine’ by Geoffrey Stavert (Cont)

Chapter 12. Excellent description of Tenna Valley which they have to cross. Pass area of Fermo and Monturano Camp. Ascoli Piceno becomes next target. Peter Gardner in spite of ankle trouble persistently carries on. They agree a party of four is too many but cannot agree how to split. They hear of parachutists and a young boy takes them to them. The door is opened by a fully armed officer who was expecting them. PO [unidentified] were 2nd SAS. After much exchange of news, plans are discussed but not details. Their offer of help as officers is politely refused. They are without uniform and as POWs should not be armed. Sent on to find Sergeant Major Marshall in the Menocchio Valley. Around Montefiore di Aso, contadini are wary but know who they are looking for and point to a house. A huge figure with a Tommy gun opens the door. SM [Sergeant Major] suggests that dressed as they are they should lie low and he finds them a house – with a bed to offer.

Chapter 13. Having been told there is a week to wait before ‘pick up’, time hangs. They find a big house full of refugees from bombing, are given minestrone but no room. They return to previous night’s space with Peter now obviously ill. A JU52 crashes and goes up in flames very near. Allied fighters often seen strafing German columns on the main coastal road.

Chapter 14. The sound of a vehicle wakes them and they dash out into cover 100 yards away. They find the Italian and his pig similarly hiding. One says he must go back for his boots. They were hanging around his neck. There is automatic fire. Is it S.M. [Sergeant Major] Marshall? (Marshall had killed one German but got away, though had lost his arsenal and supplies in the house – but the embarkation was still on.) A 40 year old Staff Sergeant with a large staff continues on his way having walked from Bologna along the roads alone.

Chapter 15. 24th October Sunday. They had holed up in a rare piece of uncultivated land covered in gorse. Their last meal is cold pasta. All the valley seems to know of the operation. They begin the walk to the beach – with no moon. They see and hear traffic on the coast road which they have to cross together with the railway line all compressed close to the beach. They arrive on the beach early, cold and anxious. Suddenly there is automatic fire. They cower down and think that is the end of the embarkation. (Judging by other accounts possibly of the same attempt it was the end for many who had to make their way back to the Italian families to whom they had made their farewells.) However, slowly other groups arrive and some of the SAS with them. Half an hour after midnight they begin to signal. For two anxious hours there is no response and then a slight splashing and a rubber boat appears. They are ferried off to a waiting ship by a variety of Naval and Army officers and men, one of whom thanks Stavert in very bad Italian for helping ‘Our lads’. At last he had made himself with such a scruffy appearance to look like an Italian – at least to an Englishman.

[Digital page 8]

[Start of Manuscript Part 1 – chapters 1-7]

FOUR FROM FORTY-NINE: A slow march through occupied Italy (PART 1)

Narrative of the adventures of four ex-POWs from Campo 49, Fontanellato, on the run in Italy in September and October 1943.

Characters:

Lieut. Harold Arthur Magee, RA

Lieut. Geoffrey Scott Stavert, RA

Lieut. Peter Gardner, Lothians & Border Horse

Lieut. Ray Pipe, Infantry

Presented to The Monte San Martino Trust

by Geoffrey Stavert, 20 April 2000.

[Digital page 9]

From BRITISH ARMY REVIEW, No. 60, December 1978

FOR YOU WAR IS OVER by Geoffrey Stavert

[Lieutenant Commander (retd) Geoffrey Stavert continues his story of his experience as a Gunner officer in North Africa, which he began in The Action at Sidi Nsir in BAR 57.]

“For you der var is over, ja?”

A German soldier actually spoke these traditional words to me. He was the commander of a Panzer Mark III, alongside which I was walking. He looked about twenty; round-featured, fresh-complexioned, not at all Teutonic – he might have been a young British officer but for his green overalls and his soft-peaked Afrika Korps cap. He spoke without a trace of arrogance or I-told-you-so, in a plain, matter-of-fact tone of voice, with the confidence of one who is used to being on the winning side and still believes that he will go on winning. There was no feeling of animosity, despite the fact that half an hour previously we had been trading shot for shot, 50mm [corrected to 88mm in the margin] versus 25-pounder, at ranges down to less than a hundred yards. On the contrary, his face had a half-smile of friendliness with perhaps just a touch of commiseration. After all, somebody has to lose, it might have said.

For a moment, just for that moment, I felt there was a little bond between us; the kind of bond you get between men who’ve been at the sharp end together, who’ve shared physical hardship and danger, or between opponents after a match that’s been fought to the limit. Not that war is to be taken as a sporting contest. Eighth Army veterans (especially those who’d been in the back areas) were fond of saying “Ah, but it was a clean war in the desert, you know”; no war is that clean, but the Afrika Korps seemed to have brought some of that kind of spirit into Tunisia with them.

He didn’t say any more. It was the only English expression he knew, and I had no German. Besides, he was too busy calling directions to the driver as his tank slithered its way along the twisty road. It was February 1943. We had been engaged in a continuous day-long battle, tanks versus field artillery, at Sidi Nsir in northern Tunisia. In the end superior fire-power and, no doubt about it, battle experience as well, had won. In a final charge at dusk the tanks had overrun the gun position, the defeated gunners had been rounded up, and now an untidy little column of prisoners was trudging off in the direction of the enemy’s back areas, shepherded by a couple Mark IIIs.

It was dark, and getting cold. The whine of the tanks’ engines mingled with the squeak and rattle of their bogies over a ground bass of the prisoners’ footsteps. The men plodded tiredly, many of them still half-stunned from the shock and noise of the battle, their shoulders drooping with despondency mixed with relief that the action, their first, was over and they were still whole. One or two had managed to snatch up a few belongings but most had no kit other than the clothes they stood up in, not even a greatcoat. In spite of the slender guard, nobody even thought of trying to leave the column. The fact is, once you’ve given up the contest, once you’ve accepted defeat in your mind, the stuffing has already been knocked out of you and it takes a very big effort to put it back again. Besides, where would they go if any of them did get away? To most of them this part of Africa might just as well have been part of the Moon.

So they straggled along in twos and threes, talking in undertones. Friend clung to friend for mutual security and comfort. Only the BSM [Battery Sergeant Major], grim-faced, mooched silently along in the rear, speaking to no-one.

“D’you think they feel we’ve let them down?” I said to the GPO [Gun Position Officer].

John was a breezy type, unfailingly cheerful even now.

“If they feel anything at all, they’re just damn glad it’s over.” he said. “Win or lose, I bet they don’t want another spell like that for a hell of a long time. Did I tell you I had a great time smashing up all the gear in the Command Post before the Jerries came in! Poured a whole bottle of whisky on to the floor, Criminal, really–“

For perhaps two miles we trudged along. The road led upwards, and we could sense the hills closing in on either side. The sense of entering forbidden territory remained strong. Presently sounds became audible through the darkness ahead, then we could make out a few dim lights, and the shapes of vehicles. Some sort of laager, evidently. The column halted, the tanks moved on, and we were directed into a field at the side of the road. An English-

[Digital page 10]

[Photograph with caption] A column of German tanks, including Tigers, moves up in Tunisia.

speaking Lieutenant explained that we should be spending the rest of the night there.

“I am sorry dere is no shelter,” he said pleasantly. “It is de same for us.”

We stood about in little huddles, trying to keep warm. It began to rain, thinly at first and then a steady downpour. Surely things couldn’t get any worse….

A Sergeant came up. From force of habit he saluted. He was one of the Numbers One from E Troop.

“It’s Gunner Jones, sir. We had to leave him. By the roadside, back there. Shot through the legs, he couldn’t walk–“

Every organisation has its Gunner Jones, the little man who seems fated from birth to be the one to whom things always happen; the one who, given that there are only two ways, right and wrong, of executing a simple task, will defeat the law of averages by the number of times he comes up with the wrong one. Even as ammunition number Jonesy could contrive to hand up the round backwards way round. Now he had bought it, the only serious casualty in Sgt Noon’s detachment.

“Christ, poor Jonesy,” John said. “We must do something. Better find that English-speaking chap, if we can. I’ll ask that sentry. Er, I say, vous. Ou est the Loitnant that sprecken Doitch, I mean sprecken English, s’il vous plait?”

“Bitte?”

“Oh, hell. There’s a man wounded, can’t somebody understand?”

“Ach! Verwundet? Ein Verwundeter Kamerad?”

One word in the verbiage the sentry did understand. He turned and shouted something. In a few moments the Lieutenant appeared, his mackintosh glistening in the rain. His face showed genuine concern at the news.

“Wait here.”

He hurried off, to return shortly driving a motorcycle combination.

“You, Sergeant. Come vith me.”

He roared off with his passenger into the darkness.

In a film, I suppose, Sgt Noon would have seized the chance to knock the officer on the head, commandeer the bike for himself, and drive back dramatically to his own lines, blowing up an enemy headquarters on the way. But things like this seldom happen in real life. Besides, both he and the Lieutenant were far more concerned about Gunner Jones.

In less than an hour they came puttering back. Sgt Noon hauled himself out of the sidecar.

“We found him, sir. We found him.” Relief poured out of him. “He’s all right. They’ve taken him off to hospital.”

We turned to thank the Lieutenant, but he had already gone; well satisfied, no doubt, that another little bit of the battlefield had been tidied up.

“H’m. Not a bad chap, that.” said John. “Quite a decent type, really. For a Jerry, I mean.”

Quiet returned to the laager. The time dragged by. We shivered in our wet clothes, stamping cold feet in the squelchy mud. I walked across the road, just for something to do. A lone sentry materialised from the shadowy mass of a vehicle. Muffled up in his greatcoat, equipment and helmet, he looked every bit as bored, sleepy and fed-up as his British counterpart would have been. He turned his back and melted into the blackness again, and for a moment I felt completely alone. In front of me, not more than a hundred yards away it seemed, rose up the bulk of a steep-sided djebel. In the gloom I thought I could detect the line of a ramp or ledge rising diagonally across it. Five minutes to get to the

[Digital page 11]

[Photograph with caption] Part of the German PW cage at Tunis.

top and over – it looked easy so long as the sentry didn’t come back….

Instead of going for it I went back to ask John if he’d have a go at it with me. While he was still digesting the idea a searchlight beam suddenly shone out, lighting up the whole mountainside. It shone only for a minute or so, then was switched off again just as suddenly, but that was enough to turn us away. Just another case of might-have-been…. Resolution is most often needed when you least feel like it.

The rain streamed down. There was nothing to do but stand there and endure it, hour after hour. It was a long, long, miserable night.

Well before dawn activity on the road, which had been quiet for most of the night, began to stir. Vehicles came and went. It began to get light, and we watched the German soldiers queuing for their breakfast. The rain stopped, and then, more welcome even than food would have been, the clouds broke up and the sun appeared. Soon, the German support column was coming through in full force and we moved back out of the way on to the rising ground behind us. We sat, gently steaming in our sodden battledress as for several hours we had a grandstand view of the enemy’s army going about its business.

From our position on the hillside we could see about a half-mile stretch of the road as it wound its way between the djebels. From end to end it was crammed with vehicles, of every possible shape and size and in no apparent order: three-tonners, half-tracks, Kubelwagen, pick-up trucks, British quads and fifteen-hundredweights in desert colours, blue Italian motor-buses with toast-rack bodywork, grey American half-tracks still carrying the white recognition star on their sides – bonnet to tailboard they ground their way westward in a seemingly endless crocodile. Practically every vehicle, too, had something hooked on behind: two-wheel trailers, four-wheel trailers, box vans, water tanks, anything. It was as if some Quartermaster down the line with a parkful of stores had stood by the roadside and simply hooked the nearest trailer on to the nearest truck as it passed him. Anything to get the stuff up to where it was needed, no matter who took it. One other thing we noticed, too. Every ten vehicles or so there was one towing behind it not an ordinary trailer but a wheeled platform carrying a quadruple set of 20mm AA cannon on a swivel mounting. In and out between them all buzzed the ubiquitous BMW sidecar outfits, like sheepdogs worrying along a reluctant flock. That German column was more like a mixed goods train on the LMS than a military machine moving up to the front.

“Christ, what a target for a few bombers,” the gunners kept saying.

It wasn’t long before we had a view of a different attitude towards air defence. About mid-morning the sound of aero-engines was heard above the traffic, and we saw the immensely cheering sight of a flight of nine Hurricanes low in the sky to the south, the sun glinting silvery on their wings. At once all was bustle below. The column halted. Men dismounted and scattered up the hillside, ourselves with them. No orders were shouted, but when the first three planes made their run in every single German soldier lay on his back, pointed his rifle or pistol up into the sky and fired it off as hard as he could go. At least four sets of quadruple cannon opened up as well with a tremendous clatter. The volume of fire put up was enormous. The whole barrage, inaccurate as it was, was enough to keep all but the most determined pilot at his distance. Only two aircraft made serious attempts to strafe the column. One well-aimed bomb blew a chunk out of the side of the

[Digital page 12]

road; another got a near miss on a vehicle. The rest, dropped from a couple of thousand feet up, exploded harmlessly on the far hillside. Two men were hurt. The damaged truck was pushed to one side, and within ten minutes of first sighting the aircraft the column was grinding off again.

As for the prisoners, we just had to sit there and watch it all. None of us wanted to see the RAF shot down, but still less did we want to be on the receiving end of their attention. Not a man but was glad to see them go. It is episodes like this which bring home to the POW the real truth of his position, that he’s been reduced to the status of an utter nobody: the man in the middle, shot at by both sides, wanted by neither. He’s become just part of the junk of war, an encumbrance to all and sundry. Some of our men even got out their yellow recognition silk squares and held them up to the aircraft, as if that could possibly make any difference. You could understand how they felt. A similar occasion arose a week later, when some of us were being taken from Bizerta to Naples, across the Sicilian narrows. Lying in the hold of an ancient Italian coastal steamer, we heard the dull boom of distant explosions which suggested that a submarine was being hunted – one of our submarines. Overhead our escorting aircraft circled protectively, a Junkers 88. We felt very well disposed indeed towards that friendly enemy aircraft then, and I don’t mind admitting it even now.

The column rolled on. Towards midday it thinned out, and it became possible for occasional vehicles to take the road back. After a little while an empty Kubelwagen drew up, and the officer prisoners were ordered down to it. Our escort was a Hauptmann of about twenty-eight, a brisk, energetic man dressed in brown pullover, knee breeches, ankle boots and puttees.

“You are to come vith me,” he said courteously. “If ve are attacked you may chump into ze ditch, but if you try to run away you vill be shot.”

We squeezed together, five of us, into the back of the little VW tourer. It bumped its way off in the direction of Mateur. After a few miles we stopped, and our escort led us over to a van-like vehicle standing by itself among a few soldiers. It was some sort of mobile field kitchen. From somewhere or other tin plates and implements were produced and we were invited to eat. It was liver stew, thick and brown and meaty; the first hot meal we’d had in two days. We ate gratefully and came back for more. It was the best Army meal I ever had, before or since.

In the late afternoon we drew up outside a stone farmhouse on the outskirts of Ferryville. We were dismounted under guard, and told to expect an interview from the Base Intelligence Officer. Another long wait. Prisoners of war are always waiting. Eventually the door opened and out stepped the IO [Intelligence Officer]. The German tenor of operatic legend: medium height, thirtyish, round face, round tummy, round steel-rimmed spectacles, immaculate in beautifully pressed service dress and gleaming top-boots. Franz Schubert in modern dress.

We tensed ourselves for the interrogation. Name, rank and number. that’s all he would get.

When he spoke it was like a singer, too, in those high, syrupy tones which only German tenors really manage.

“Good efening, chentlemen. I am sorry to haf been keeping you waiting. but for you ze var is over now, eh? Zere is only von question vhich I vish to ask you. Ve already know ze name of your unit and all of yourselves, but zere is one officer whom ve haf not yet been able to trace: Lieutenant Magee. Can any one of you tell me vat became of Lieutenant Magee, please? Ve are worried about him.”

We were impressed, not to say taken aback. He hadn’t even said ‘We have ways of making you talk.’ Magee had been F Troop’s OP [Observation Post] Officer on Hill 609, and nothing had been heard from him since the attack had broken at dawn the previous day. We could not have helped the IO [Intelligence Officer] even if we had wanted to.

“Very well chentlemen, thank you. That is all. You vill remain here tonight. I fear ze accommodation is not good, but you will soon be much more comfortable in ze base camp at Bizerta.”

Well, that was something. Maybe there we should be able to get organised properly, and devise a means of breaking out. In the meantime what we all needed most was some sleep.

We were locked into a loft above a nearby guardroom. There was no furniture of any kind, so we disposed ourselves variously on the bare boards. Sleep came readily enough. In the middle of the night the door was thrust open and in came the cheery figure of Magee. We welcomed him like a long-lost brother; it was just like having the family complete again. He told us how an infantry assault with mortars had caused his OP [Observation Post] to be abandoned soon after dawn. He had managed to make his way down the far side of the mountain and had found shelter in some rocks where he intended to lay up until nightfall. Late in the afternoon an Arab shepherd had stumbled across him by accident. On finding that he was alive and therefore not an object of loot the man had gone away, only to return a few minutes later leading a German patrol.

We could visualise the look of quiet satisfaction on the German Intelligence Officer’s face as he ticked off the last name in his book; 155 Battery, all properly accounted for.

Early in the morning we were called by the Guard Commander, a smart young NCO [Non-Commissioned Officer] who looked as if he was hardly out of school. He did not shout “Raus” in Colditz fashion; he apologised in good English for not offering us breakfast. They were not provided with rations for such emergencies, he

[Digital page 13]

explained, reasonably enough. However, he had borrowed his men’s mugs and was able to give us all a drink of ersatz coffee. While thus engaged he treated us to a little homily on the folly of entering the war on the wrong side. As everyone knew, the real enemy was the Bolsheviks. Time would surely reveal the truth of his words. There was absolutely no possibility of Germany’s being defeated, and the sooner misguided persons like ourselves came to realise this, the better it would be for all concerned.

The truck arrived which was to take us to Bizerta, and he saw us off with a smart salute. We were stiff, dirty, unshaven and hungry, but Magee’s return had brought a revival of spirits. The trauma of battle was receding fast, and the feeling was growing in some of us of a need to do something to redress the balance of our present situation. There was some discussion in the back of the truck as to the best way of disposing of the two guards before jumping out and making a run for it, but nothing transpired. For one thing, the truck was moving too fast. For another, it’s very difficult to get a group of officers to agree on anything, unless some individual, by virtue of rank or outstanding personality, is able to emerge as clear leader.

We arrived at the base camp about noon. The word “camp” is not quite the right one to describe what awaited us there. For the Bizerta camp was nothing more than a cage: just a square of open field on the outskirts of the town with a double barbed wire fence around it. No roof, no tents, no shelter of any kind. No latrines, no ablutions, no cookhouse. Between two and three hundred soldiers and half a dozen officers were already in this cage. The sole supply of water for this body of human beings came from a single standpipe at the gate. When we arrived this was dry, and it remained so for the rest of the day and all that night.

An infantry Captain seemed to have appointed himself senior officer among the prisoners. He was a big man, thirtyish, thick moustache, a shop manager in civil life. He didn’t exactly welcome the new additions to his flock.

“There’s no effing water,” he said. “Hasn’t been any all day. I’ve been on at the Eyeties to get it working, but all they do is waggle their hands and say the Raff have bomba’d the works. Useless little bastards. It’s an effing bad show here all right, I can tell you, ‘Domani’, that’s all you can get out of ’em. Everything’s domani.”

He bullied the Italian Lieutenant in charge of the cage unmercifully.

“Now look here, Tenenty. We want mess-tins, tools, and food, see? Food! Quelque chose amanger, comprenny? And PDQ. Chop chop. This whole show is effing disgraceful. Well, are you the responsible officer or are you not?”

The Italian waved his hands and shrugged hopelessly. It was not that he was being deliberately negligent – the problem was simply far too big for him. He looked near to tears. Any one of us could have felt sorry for him, if we hadn’t been more sorry for ourselves.

There was no food, nor water, for anyone that day. After dark it came on to rain, and for the second night in three we had to endure hours of cold and wet. Ironically enough, next morning the water tap came weakly to life; a long queue of men formed, many of them having to drink from their hands. Then towards midday a truck drew up and deposited a huge iron pot at the gate. A thin macaroni soup slopped about inside it.

The infantry Captain seized the ladle.

“Right, line up,” he shouted. Then to my amazement he served himself a brimming mess-tin full, and rather less to any other who had a container. After this he turned to one of the NCOs [Non-Commissioned Officers] who was standing by, expressionless.

“Right, carry on Sar’nt,” he said airily. “See that every man gets a fair share.”

Feeding two or three hundred men out of a single container was the sort of Biblical task that was no concern of his.

Adversity brings out the best in some people and the worst in others, and perhaps it was this little episode which brought some of the rest of us to our senses. We had already recognised some of our own gunners among the soldiers, men whom we knew would respond to instructions from their own officers. The infantry Captain was quietly deposed. We divided the men up into platoons, and shared out the NCOs [Non-Commissioned Officers] among them. We got parties organised for digging and other fatigues. Gradually, the harassed look faded from the Italian Lieutenant’s face. When he was presented, not with abuse but with a piece of paper showing by numbers and drawings a list of the items needed: shovels, forks, dixies, disinfectant – he began to look quite enthusiastic. Within twenty-four hours he had provided them all. Better still, he found some blankets; thin, threadbare, half-sized they might be, poor things indeed compared with the genuine grey British article, but more than welcome all the same.

We stayed in that field for a week, without ever having enough water for a wash, let alone a shave, and on the same semi-starvation rations. If that doesn’t sound a long time – and many prisoners in the desert, both Allied and enemy, had to spend up to a month in the cages – it certainly felt like it.

At the end of the week the first batch of prisoners, including all the officers, was lined up for transport to Italy. The Italian Lieutenant was there to see us go. He ran up and down the line, fussing like a mother hen with her chickens.

“Auguri, auguri,” he kept saying. He even tried to shake hands. And then, on a sudden thought, he came out with the only words of English he knew.

“Forra you da war isa over, si?” His smile was pure envy.

For some of us, he was wrong. But that’s a different part of the story.

[Digital page 14]

From BRITISH ARMY REVIEW, No. 62, August 1979

The French Hut at Campo 66

Lieutenant Commander G S Stavert MBE, RN (Ret’d)

“Dear Folks,” I wrote, squeezing the writing up to get as much as possible on to the single page of the Airgraph form, “By now you will have heard that at least the worst is over. We were overrun by German tanks and most of the Battery were put in the bag, but we gave them a good scrap for it first. Please note that it was the Germans who captured us, and not repeat not the Italians – they only handed us over to the Italians afterwards for safe keeping. We are at Campo 66, which is at xxxxx near xxxxx. Magee and I are sharing a hut with a crowd of French Foreign Legion officers. I shall be able to write to you once a fortnight. Much love. Keep well, G.”

Campo 66, whose location the Italian censor had for some reason thought it necessary to delete, was outside the town of Capua, some twenty miles north of Naples. It was used as a staging point for prisoners brought over from North Africa, before moving them on to more permanent camps up country. Seen from the outside, the rows of wooden barrack huts and barbed wire fencing looked every bit as gloomy and depressing as you might expect. But, once he’s on the inside, the prisoner doesn’t see his gaol with quite the same eyes; the horizon draws in, the world contracts, and the human creature, adaptable being that he is, adjusts himself to his new environment as far as physical conditions and his temperament will allow.

For officer prisoners at Capua the world was a rectangle of flat, sandy ground measuring about eighty yards by sixty. Inside this enclosure were four single-storey huts, an ablution shed and a crude cookhouse. Huts 1 and 2 housed British officers, between forty and fifty in each. Hut 3 held a similar number of French officers, members of a Regular battalion who had been picked up in the winter fighting in the Tunisian mountains around Pont du Fahs. Hut 4 was reserved as a dining-room, canteen and general “admin” building.

At first the international boundaries were strictly preserved. The French officers never visited the British, and the British never visited the French. In March 1943 however, when a consignment which included the survivors from Sidi Nsir came over, the numbers became too great for the British huts to absorb. Magee and I, as the junior members of the new intake, were detailed to be the overflow and drafted into Hut 3. At first, somewhat naturally, we felt rather put upon. To have to muck in with a crowd of strangers, and foreigners at that, went against the grain. But the French were courteous and friendly. They made space for the extra two places without complaint, even though there was less than a metre between beds already. They showed us how to construct shelves for our few belongings out of bits of string and cardboard from the Red Cross boxes (for a bed and a stool was all the furniture you got). They even shared a cup of precious tea and generally treated us as companions in misfortune.

The initial reaction of the average POW, once he’s reached the static situation of his first proper camp, is to revert to childhood. His spirit has already been weakened by the shock of battle and the privations he has endured in the period immediately following his capture. Now, suddenly, he finds the last vestiges of responsibility taken from him: his responsibility for carrying on the war, for looking after his juniors, even for finding the ordinary necessities of life. True to form, the new intake at Capua lay on their beds all day, neglected their appearance, and went generally to pot. The expression ‘drop-out’ had not then been invented, but that is what the new men became. Like today’s college students, they all grew beards. In many cases this was not altogether avoidable. I had only the clothes which I’d already been living in for three weeks. I had no razor. Toilet gear was obtainable from the Campo canteen, but at ten shillings for a single blade (at home they were less than a shilling a packet), and an Italian blade at that – you were lucky if you got one decent shave out of the two edges – I was going to have to save up for a month before I could even get started.

The French had already passed this stage, if indeed they ever experienced it. They were Le Troisieme Etranger, and proud of it. They had standards to keep up, and didn’t mind showing it. Besides, they all seemed to have plenty of spare shirts. It was not many days before Magee and I

[Digital page 15]

began to take our cue from them and smarten ourselves up a bit.

The hut was presided over from his bed at the end near the door by the senior Major, a rotund, fatherly-looking man of about forty-five. Discipline was excellent; his authority was never questioned, so he had no need ever to exert it. “Bon joor, mong Commondong,” Magee and I would say politely each morning. ” Bonjour l’Etudiant. Bonjour Monsieur Maggie,” he would reply with a friendly nod. They were keen on nicknames and I became The Student from the day we arrived, but Magee was always Maggie to everybody.

There were two other Majors. Le Medecin, whose real name I never got to know, was a slim, dark, fastidious man in his late thirties, with delicate hands and a toothbrush moustache. Like most of the Frenchmen he was a heavy cigarette smoker, and the Red Cross ration was not nearly enough to satisfy his needs. Every morning, by arrangement with the guards, a young soldier from the troops’ compound would come in and silently present him with a packet. He would then lay out the daily supply on his shelf, so many each for morning, afternoon and evening. When he had smoked one down to about half an inch he would spike it on a pin and carry on for a few more puffs. Then when it seemed that ignition of his moustache was imminent he would expertly flick off the glowing tip and put the microscopic butt away in a little tin. By the end of the day he had accumulated enough to roll one extra for the morning. Like Sherlock Holmes’s pre-breakfast pipe, his first smoke of the day was composed of the previous day’s leftovers.

Le Medecin shared parcels with Maurice, the Adjutant, a young Captain who was every bit as tidy and self-composed as he. The third Major was Le Commandant Lebrun – but I’ll come to him later. The remaining officers ranged from middle-aged Captains down to Lieutenants in their twenties. Not one of their senior officers could speak a single word of English. Nor could many of the others. Those few who could, however, spoke it very well. Magee and I made do in a rough and ready way with our School Certificate French, but there seemed to be no equivalent of this level of attainment among the French. They were either fluent or, mostly, they had no English at all.

The great thing about the French hut was that it was organised. It ran to a system. It was peaceful.

The daily routine began with roll call. This was a movable event which took place at some time between 0800 and 0900, depending, we supposed, upon when the Capitano had got up. After roll call, those who had not yet managed to wash joined the ablution queue. Washbasins were provided on a scale of one to about thirty men and, of these, at least one would not be working. (Mussolini may have made the trains run on time, but he was a failure as a water engineer.) Then, the French hut was tidied up. Every officer stripped his own bed, folded his blankets and stacked them neatly at the foot in proper barrack style, clearing the rest of his kit from the floor and stowing it on the bed or on his home-made shelf. Then two French soldiers came in from the other compound and swept out the hut from end to end. By 1000 hours the hut, despite its forty-odd beds, was looking clean and almost spacious.

The British huts, on the other hand, always had the appearance of a badly-run school dormitory in which perhaps a couple of grenades had gone off. Not a single bed was made down; most of them were just as the occupants had left them when they got out that morning. The floor would be littered with clothing, boots, Red Cross boxes, half-empty food tins, bits of rotting cabbage and other material, supposed consumable, salvaged from the cookhouse dustbins. Some men would be eating, some stood about wrangling, some just lay on their beds for hours on end. At the far end of one hut Blanco White, a Quartermaster, was making an elaborate cooking stove out of empty food tins. Bang, bang, bang, he went, hour after hour, adding his mite to the general din and confusion. He was still working on it when Magee and I moved on in May.

It was a relief to return to the peace and quiet of the French hut after visiting our friends in Hut 1. By mid-morning it would be largely deserted, most of the occupants having proceeded to the dining hut for the morning’s activity. The professionals of the Legion, having long since discovered that war is ninety-nine per cent boredom, had devised their own way of filling the empty hours at Sidi-bel-Abbes and elsewhere. They played cards. All day and every day, they played. Each officer had at least two packs of playing cards in his kit. The routine was always the same: in the morning they played patience; in the afternoon it was gin rummy; then in the evening they made up their fours for the serious business of the day, Le Bridge.

One man who might have remained behind in the hut was Le Maestro, the Bandmaster. A mild-mannered little man with a bushy black beard, he spent hours at the foot of his bed working away at abstruse exercises in harmony. His working desk would be two stools, his manuscript paper a toilet roll. With pencil and straight-edge he ruled out his staves on each sheet with meticulous accuracy, giving as much care and attention to this preliminary stage as he did to the exercise itself.

One other who was not in the habit of playing patience was the third Major. Le commandant Lebrun was a tall, spare man of about forty, with a florid, mobile countenance and prominent veins on his forehead which stood out as if he lived in a state of permanent mental stress. Dressed always in his field uniform of grey jacket, breeches, puttees and soft boots, he could invariably be found pacing the hut, alone. Up and down the aisle between the beds,

[Digital page 16]

hands clasped behind his back; left, right, left, right, about turn, to and fro, he carried on his solitary patrol, his thoughts heaven knows where. He spent most of his days in this fashion. Often his footsteps would be the first sounds you heard on waking, for he was always up long before anyone else. He never joined the marchers who sweated it out in the compound, pounding two by two in the sunshine. He never came on the escorted walk which, apart from parcels day, was the high spot of the week. He took his exercise by himself, in the hut.

He seemed to have no special friends, and his forbidding appearance did not encourage conversation. It seemed the form just to accept him as a harmless part of the scenery. Until, one day late in April, a further intake arrived. The beds were squeezed up a little more, and the population of the French hut was enriched by the addition of four Guards officers. They wore Eighth Army gear, with LRDG [Long Range Desert Group] on their shoulder flashes.

Now Guards officers, as we all know, live on a different plane from the rest of us, and are not subject to the same inhibitions. One of these was a merchant banker and another a Baronet, which I suppose represents a fair cross-section. Beyond passing the time of day politely with their immediate neighbours they did not socialise much with the lesser orders. Le commandant Lebrun, however, was a phenomenon worthy of further examination. One morning a week or so after their arrival, therefore, the astounded Major was halted in his tracks by a loud, high-pitched voice from one of the nearby beds.

“Pardong,” it said, “May poorkwa le Commondong marsh toojoors dawns lar hut, may nalley par jamay sure le marsh dawns tar comparney aveck lays owtrers offiziay, see voo play?”

Lebrun glared. His eyes bulged. His hands clasped and unclasped. His face turned dark, his lip curled, his veins stood out like pieces of string. When the words came he spat them out like broken teeth.

“C’est parce que, je ne veux pas marcher avec un monsieur italien qui porte un fusil a cote de moi!”

They left him alone after that.

Around mid-morning Magee and I usually made our first mug of tea. We relied a lot on tea to try and persuade our stomachs that a normal quantity of food was on its way down. We generally made our first brew at about eleven, and then boiled up the same lot of tea-leaves for a second pot after lunch. At tea-time we made a fresh brew, re-cooking these leaves for the evening drink. Treated with care in this way the Red Cross supply could just last a man for the week.

All private cooking had, of course, to be done out of doors. The French were very good at making open-air stoves out of mud and a brick or two, with bits of barbed wire for the griddle. They were far superior to our own crude boy-scout efforts, so we soon gave up the struggle and used theirs instead. Easily the best of the French stoves was Le Maestro’s. It was a model of neatness and elegance, yet it had a draught like a steam-engine. At most times of the day you would find a queue of three or four men lined up at this stove, with perhaps Le Maestro himself among them, a resigned look on his face as he patiently awaited his turn to use his own apparatus.

Now and again some oaf would knock part of the structure away with his boot, or break the grill with too heavy a load. There would then be a period of irritable waiting for the inventor to repair the damage. Nobody ever owned up, but messages would come through from the other hut. “Look here, old Bandy’s stove has bust again. Ask him when he’s going to get it mended, will you?”

From time to time one of the Frenchmen would decide to do a little metalwork. Before starting the job he would gather everything he needed, place it all convenient to hand, and then seat himself at the end of his bed, stool between his knees, so that his task could be accomplished in proper physical comfort. Then he would take a cylindrical biscuit tin, remove the bottom, open the seam, flatten, cut and shape the metal till in a couple of hours or so he had fashioned an immaculate little cigarette case, complete with hinged lid, as clean and neatly turned as a machine-made article. Meanwhile, in the distance, the sounds of Blanco bashing away could still be heard, perhaps it was a complete kitchen range he was building, not just an oven.

And so to lunch. There was no seating in the dining hut, so we had to pick up our stools and cart them in with us. For anyone who has a taste for Italian food, it may be of interest to list the daily POW menu:

Breakfast … Coffee substitute, one cup. Rolls, small, one.

Lunch … Soup, thin, dishes, one.

Supper … As lunch.

(Other ranks got this free, but officers suffered the additional insult of having their pay docked six shillings a day messing charges.) It requires no effort of imagination to appreciate just how much the Red Cross parcels meant. They were issued on a basis of one between two, twice a week. Both kinds, English and Canadian, provided marvellous variety of essentials but our greatest shortage was of bread, or at least of grain in some form. It was a matter for endless discussion with one’s partner as to how to allocate the day’s one bread roll: whether to eat half at lunch and half at supper, or scoff it all at once and starve till tomorrow, or to scrape out the middle to use in making rissoles.

Magee and I used to save up most of the Red Cross food for a meal in the evening. Magee kept the opened tins on a shelf behind his bed. I often wondered if he ever sneaked in and stole a sliver of cheese or a dab of condensed milk when no-one was looking, like I did. Almost anything could happen to

[Digital page 17]

a tin of corned beef. We would mix it up with breadcrumbs, broken biscuits, bits of old cabbage stalk – anything to give it more bulk and weight than it originally possessed. Men would diligently search the rubbish heap behind the cookhouse, hoping to pick up the occasional potato peeling from which a bit of sustenance could still be scraped.

The Frenchmen, on the other hand, did not strive so desperately for sheer volume. They preferred to use the Italian meals as a basis, and supplement them with Red Cross food on the spot. A tin of bully was a nice, compact package, and they preferred to use the contents in their natural state, rather than convert them into a large but messy hash. For the most part they cooked comparatively little. I used to wonder if it took up too much time from the cards.

The afternoon hours were those which dragged the most. We often talked about escape. Magee had a scheme which appealed to me. Neither of us thought much of the usual idea of travelling north and getting across the border into Switzerland. His plan was much simpler. “We’d make for the coast, near Naples, say, and pinch a little boat. We could sail over to Bizerta, if our chaps had got there. It’s only ninety miles across. Or Malta, even. Have to go round Sicily, of course. No problem – turn left past Palermo, you couldn’t miss it -.”

Neither of us had ever sailed a small boat before. We had no charts or compass. Still, it was a grand scheme.

The French never discussed escape. They had no Escape Committee of their own, and they never bothered the British one. You got the impression that the question had been discussed at some earlier period, and duly rejected. They seemed to have a way of making up their minds on a course of action, of rationalising the arguments and, once a conclusion had been reached, of putting the former objections and alternatives out of mind, so that everyone appeared satisfied with the decision and committed to it.

“Echapper? Comment?” Shrug. “C’est impossible.” End of discussion.

Perhaps they were right. It was not so much that they were resigned to their fate, as that they had learned how to accommodate to it. Captivity was a fact of life, and they adjusted accordingly. Besides, it was not their fault that they had had to oppose German tanks with horses and obsolete artillery. In any case, it was confidently expected that the Vichy Government, whom they all despised, would in due course repatriate them. So why bother?

The British, deep down, never really accepted this point of view. Hence their untidiness, the abortive escape schemes, the sudden outbursts of ill-temper. We tried to do useful things. We gave lectures, organised brains trusts, learnt the Morse code. We started a choir. It was not easy, without any music, to conscript members. Eventually, with the aid of some of the rugger players, we managed to construct a two-part rendition of Cwm Rhondda, with bathtub harmonies –

Bread of hea-hea-ven,

Bread of hea-hea-ven,

Feed me till I want no more -haw-haw-HAW…

The French held auditions, from which they selected about half their volunteers. After a couple of practices the sounds which emerged from the dining hut were of such beguiling liquidity that even the dedicated marchers stopped to listen –

J’attendrai,

Le jour et la nuit

J’attendrai toujours….

Compared with us they sounded like the Glasgow Orpheus Choir. Perhaps they included singing, as well as contract bridge, in the syllabus at St Cyr.

Easter Sunday was coming, so it was decided to put on a bit of a show, just to show the Italians that we could still do it if we wanted. I slept on my one and only pair of trousers. I even started to work on my boots. But what I really wanted, almost more than anything else, was a collar-attached shirt. In those pre-nylon days shirts were made from wool or cotton and were almost invariably collarless. Other ranks wore the battle-dress tunic done up to the neck, but officers were collar-and-tie men. With one shirt and a set of clean collars you could keep up appearances all week, but with no collar at all you felt horribly undressed and working-class. Tropical shirts, which were designed to be worn open-necked and jacketless, were of course made with collars, but First Army had not been issued with tropical kit. Sweating damply under the Mediterranean sun in our thick green shirts and heavy serge trousers, with our braces tied belt-fashion, we felt uncomfortable, ungainly, unmanly almost. We envied the Eighth Army men in their cool-looking khaki drill, their shorts and their swanky desert boots. We felt that we were the amateurs and they the professionals – an impression which they themselves took no trouble to discourage.

Until that Easter Day, when the French succeeded in upstaging everyone. They didn’t so much come on parade as make an entrance. Every one of their officers was gorgeous in full Service dress, complete with Number One uniform, polished buttons, burnished leggings, coloured kepi, everything. They fell in immaculately, standing stiff as a row of de Gaulles while the rest of us goggled at them. Where had they got all this kit from? Magee and I had known that they were better provided with spares than we were, but not to this extent. What kind of a battle was it, that had enabled each one of them afterwards to walk into the bag carrying two packed suitcases? We asked Maurice, but he was vague. “C’etait arrange,” was all he would say.

Six o’clock. The bugle blew, the second dish of soup was served, then Magee and I made our own meal. A small tin of salmon (John West’s, of course; nothing but the best went into those Canadian

[Digital page 18]

parcels) ground up with a few cream crackers and cooked over Le Maestro’s fire, could be made into quite acceptable fishcakes. It meant using the last of our precious butter ration, and we had to chisel them off the pan at that, but it was worth it.

Meanwhile the French hut came into its own. Tables were brought in, blankets spread, the cards produced and partnerships settled for Le Bridge. The games went on without a break until lights out at ten-thirty. Sometimes they played with single tables, but very often they ran duplicate tournaments, carrying the boards from one table to the other with as much care as waiters in a General’s mess. In the smoky, dimly lit hut with its crowded beds and festooned walls, we forgot for a few hours the floodlights and the wire outside and lost ourselves in the cheerful company and excited shouts of the players.

All the Frenchmen could play, and some of them were very good. Easily the best of them all was Commandant Lebrun; tres fort, he was, not to say formidable. It was an education just to watch him. Here at last was an outlet for some of his bottled-up nervous energy, something he could get his intellectual teeth into. With the cards in his hand his eyes lit up, animation spread across his features. He didn’t even bother to sort them into suits, but sat drumming his fingers, impatiently waiting his turn to bid. When playing the hand himself he seldom went through more than three rounds in detail; then down would go his own hand on the table – the missing trumps all covered, every finesse and cross-lead worked out, five diamonds called and made with no possibility of argument. When his turn came to be dummy he would leave his seat and stand breathing down his partner’s neck, silently willing the poor man to make the correct play. When the opponents played the hand he flipped out his discards with studied contempt, and was massively scornful afterwards:

“Et pourquoi n’as-tu pas joue le trefle, mon capitaine? Mon partenaire a joue le roi; il faut donc que la reine soit a moi. Pah!-.”

So, the evening at last went by till the bugle sounded once more, the tables and cards were put away, and one by one the French hut prepared for bed. Those who had pyjamas got into them, those who had not got into their spare shirts, and those who had no spare shirt got into the blankets in nothing. “Goodnight Maurice.” “Goodnight Maestro.” “Bonne nuit l’Etudiant.” The sounds in the hut died down. It was silent out in the compound too, save for the occasional footsteps of a lone sufferer hurrying towards the bog. The glare from the floodlights shone in through the open windows casting barred shadows on the opposite wall, a renewed reminder of our status. You closed your eyes and thought of home, food, girls, food, FOOD; you fought your battle over again for the umpteenth time, waiting for sleep to come.

But not quite yet. Two beds away from me lived a wizened little man with a trim spade beard, known as L’Ancien. L’Ancien was harmless but he had a routine which was all his own. His idea of sharing a parcel was to open all the tins the moment it arrived and cut everything in half. He was good at opening tins and took a lot of trouble over it, slicing both ends off the can so that the meat roll slid out in a neat cylinder, instead of having to be dug out piecemeal. Then out would come his Swiss ten-bladed knife and with a single slice the two halves would fall apart, exact to the millimetre. He even counted out the sheets of toilet paper, “Une pour moi, une pour vous…. “

In particular, L’Ancien liked a little snack last thing at night; just a couple of digestive biscuits, after he’d got into bed. You could hear him getting out his tin, rustling the paper lining, plonking the biscuits, one, two, on his plate. Then other sounds: chomp-chomp, snuffle, glump; chomp-chomp, snuffle, glump – there was genuine appreciation in it. Beds creaked, bodies stirred, a muttered “Merde” came from somewhere down the line. But nothing put him off….

Being a prisoner of war may have had its advantages for Harry Flashman, but it’s not a state to be recommended, even in “civilised” war. It’s like being out of cigarettes on a Saturday night in Wales, when you suddenly realise that tomorrow is a Sunday and everywhere will be shut. But the day after that is a Sunday too, and the next, and the next…. It’s the indefiniteness of your sentence which is the worst feature, I think.

In a couple of months Magee and I were moved on to Campo 49, in the Lombardy plain. The French stayed behind, still expecting to be repatriated. We said goodbye to our particular friends, but never went to the extent of exchanging names and addresses. Somehow it didn’t seem an appropriate moment, but I’ve often wished since that we had done. So far as it was possible to enjoy anything at Capua, we had enjoyed their company, and I think benefited from it. Of one thing I was quite sure. Next time, if there was a next time, I’d make certain that one item in my survival kit – besides a clean shirt, that is – would be a pack of playing cards.

[Digital page 19]

[Map: Detailed map of Emilia-Romagna, centred on Bologna. Going up to Venezia [Venice] in the north, and down to Firenze [Florence] and Siena in the south.]

[Digital page 20]

[Map: Detailed map of the coast of Emilia-Romagna, the Adriatic Sea, and what is now the north-western part of Croatia.]

[Digital page 21]

GOODBYE CAMPO 49 (A Slow March through Occupied Italy)

AUTHOR’S NOTE.

This is a true story. All the events took place just as I have described them. One or two names have been altered, but no character has actually been invented.

I am grateful to the Editor of the British Army Review for permission to include material in the first three Chapters which has previously appeared in the Review.

GSS. [Geoffrey Stavert]

[Digital page 22]

1. SIDI NSIR, 26 FEBRUARY 1943.

At six o’clock, just as the light was beginning to fade, the tanks came in. Until then it had been a good battle. All day we had managed to hold them off, firing round after round of gunfire at about 3000 yards range. In between we had endured mortar and machine-gun fire and strafing by fighter-bombers, but the tanks had kept their distance. So long as they did, we felt we were in with an even chance; another half hour and it would be dark – with any luck then they’d call it off. But then came the ominous report from the OP [Observation Post] that the tanks had started to move. The gunners exchanged nervous glances, and shifted themselves a little closer in behind the gunshields. For the first time, a finger of doubt about the outcome began to creep in…

The early dash for Tunis in the autumn of 1942 had petered out through lack of men and supplies, aggravated by the onset of bad weather. The Germans had managed to set up blocking positions across the three main routes through the northern mountains: on Green Hill and Bald Hill in the Sedjenane valley, on Longstop Hill above Medjez, and in the hills to the west of Mateur. A period of temporary stalemate had set in, in which relatively slender British and German forces sat in static positions peering towards one another through the curtains of winter rain, while the race to build up reinforcements went

[Digital page 23]

on behind them. Away to the east Rommell’s Afrika Korps was methodically back-pedalling towards Mareth in front of the advancing Eighth Army. General von Arnim, in command in Tunisia, was flying troops from Italy into Bizerta as fast as he could pack them into his aircraft. On our side we had the French and the Americans to the south; more convoys were on their way from England, and more Americans were pushing their way eastward from Algeria and Morocco. Sooner or later a crunch was bound to come; but what you seldom feel, in this kind of situation, is that it will fall on you yourself.

Into this arena, at the beginning of February 1943, came a battalion of infantry, the 5th Hampshires, and their supporting Gunners, 155 Field Battery RA. Both were fresh out from the UK; a fortnight by troopship to Algiers, an eighteen-hour dash by destroyer to Bone, a week in a transit camp sorting out vehicles and equipment, then a night move over the mountains into Tunisia. They were assigned together to form an advance patrolling base at a place called Sidi Nsir.

Sidi Nsir was no more than a single building, a halt on the single-track railway which threaded its way eastward through the hills from Beja to Mateur. The battery moved up into position overnight. In the early morning light the gunners, weary after the long drive in the darkness, gazed around them apprehensively at their new surroundings. A grey, rain-soaked sky revealed a strange, bare landscape of undulating moorland intersected by steep, rocky hills called djebels, with unpronounceable second names. From Sidi Nsir station the road wound right and then left

[Digital page 24]

round the shoulder of a low hill, forming a wide s-bend astride which the battery stood: the four 25-pounders of E Troop in rear, lining the road, and F Troop a few hundred yards forward, out of sight over the crest. Battalion Headquarters of the 5th was in the station. D Company occupied the rising ground between our two Troops. The remaining companies were sited to guard the flanks and front of the position. Before us a tumbled mass of hills blocked the way to Mateur and the Tunis plain. Behind us lay the wide green valley to Beja, limp and soggy after its winter wetting, with the solitary road snaking down the middle; a lonely, Scottish Highlands type of road, single width, with very few passing places. Four miles back was Hampshire Farm, where B Echelon and the vehicles were. Twelve miles back, in front of Beja, were the nearest troops of the British First Army.

Away to the right rose Hill 609 – it was easier to call them by their heights (in metres) than to get your tongue round their Arabic names – a rocky djebel from the top of which F Troop’s OP [Observation Post] Officer could see nearly all the way to Tunis, forty miles away. And all around, on either side of the valley and beyond, the lesser djebels pointed their sharp-ridged backbones to the sky, rearing and twisting in saw-toothed silhouettes like the spines of some fabulous monster. E Troop had a rear OP [Observation Post] which was on a knife-edge. You could sit on the top with one leg in 46 Division’s area and the other in 78 Division’s, and from it you could see more djebels at once than from any other point in northern Tunisia. It looked what it was, a country well suited to fighting a war over.

Soon, the petrol cookers were roaring and a hot drink

[Digital page 25]

brought new life to tired limbs. The guns were properly sited and laid on their zero-lines, and then it was time for the real work to begin: the digging. Whenever the army settles itself for a few hours in one place it starts to burrow its way into the ground as if consumed by a perpetual urge to find coal. Digging in the Tunisian soil was like thrusting your spade into an exceptionally solid Christmas pudding. Large masses of it clung tackily to the blade and refused to be thrown off. Worse, it stuck to your boots in such glutinous lumps that after a couple of days you felt you were developing ballet dancer’s leg muscles. But shelter was an immediate consideration. Not a tree, not a bush rose to break the force of the elements. It was like camping out on the top of Shap Fell, say – without tents. Gradually, as the days went by, a neat rectangular Command Post, properly sandbagged, grew out of the earth, and each gun acquired a semi-circular pit with lean-to shelter attached. By the end of the first fortnight we were beginning to feel quite experienced campaigners.

There were a few local inhabitants, but we tended to regard them as beings from another world. Here and there a little huddle of beehive huts showed where they lived, and now and then a barefoot boy could be seen tending a few dozen goats. Mostly they seemed to live at night, for nobody could have slept through the racket which their awful dogs kept up from dusk till dawn. In fact none of us knew quite what to do about the Arabs. Occasionally a moth-eaten specimen would come wandering through the lines, to be greeted by the customary challenge:

[Digital page 26]

“Oi, Abdul! Any erfs?”

Abdul would make what passed for him as a smile, and snarl something unintelligible – whether Arabic or French, it was all the same to the gunners. In due course the deal would be done, the eggs handed over, and he would depart on his way clutching his tin of bully. If his way happened to lead along the road towards the enemy, nobody thought of stopping him. In any case, the enemy already knew where we were; he sent a couple of Messerschmitts over every day to look at us.