Summary

Maurice Goddard recounts his journey down the spine of Italy to reach Allied Lines in 1943. Alongside him was Erik Humpson, and fellow Allied troops. They battled the environmental conditions over an extended period, and found civilians willing to help, but all were apprehensive of the security risk that faced them. These were housed, clothed and fed by these civilians and experienced close encounters with German and Italian soldiers.

His story is reproduced here by kind permission of Gunner Publications who are the copyright holders for this article.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital page 1]

An Epic Journey.

Though Maurice Goddard was among the Trust’s first supporters, and his daughter together with Ian Laing “upped” the Fontanellato lunches, only recently has the Trust received for its archives the story of his epic journey with [name redacted in the original] down the spine of Italy to reach, through the snow, Allied Lines on 1st December 1943.[Name inserted] Erik Humpson.

Being in Fontanellato he was fortunate in having as [in original text] O.C. [Officer Commanding] [Overwritten. SBO. Senior British Officer.] of the Camp Hugo de B Bergh who together with the Italian Commandant let all the POWs (some 600 of officers) out of the camp. The further south they went so the going got harder as the reached the heart of the Appennines around the Gran Sasso. They had passed through the area of Bardi where many families had connections with Wales. Everywhere however, they received food and [word redacted in original] shown hiding places to sleep. Civilian clothes were supplied but essential army boots were retained. Having to cross a road after the Futa pass they dodged German soldiers on foot and German traffic.

They were directed to a mountain cave where nine Allied men were hiding, one of them seriously ill – all waiting for the Allies to reach them. Further on they saw more Germans and heard gunfire from the front line. Ice added to their difficulties as they kept to the hills until descending to the Sangro river. The noise of the river and the chopping of wood by some Germans saved them from a close encounter. Now joined by a Free French soldier they decided the Sangro had to be crossed so stripped naked with clothing and boots on their heads they started across the river. The Frenchman slipped but holding staves between them and Erik standing firm they righted themselves and got across. They could hear dogs barking and thought they saw their silhouettes – fortunately it was sheep.

They saw a patrol a few yards away. In a wooded area they thought they heard voices which might be English and saw shells falling on a nearby hill. Suddenly the Frenchman jumped up “Soldat Anglais”. The first fellow countryman on Allied soil they had spoken to for 18 months. They were led away to breakfast on 1st of December – home if not quite dry.

[Digital page 2]

[Text added to original.] ‘THE Gunner’ 1979.

Escape Route Re-visited

by Major K M Goddard, late RA [Royal Artillery]

Those of your readers who were in Italy during the 1939-45 War may be interested in the account of a recent journey made by four wartime officers of the old 28th Field Regiment RA [Royal Artillery] (1 Blazers, 3 Martinique and 5 Croix de Guerre Btys) who were taken prisoner in the Western Desert Cauldron battle of June 1942 and. after 15 months imprisonment in various Italian POW camps, escaped into the Apennine mountains and walked 500 miles to rejoin our forces on the River Sangro or Gustav Line.

The desire to return and retrace that route had been in the minds of all for many years, and now, with ages totalling 260 years, it was becoming obvious that if the attempt was to be made then it should not be longer delayed.

With the acquisition of a motorvan and tent plans were made in the Spring of last year and detailed route maps, timings and provision lists prepared. The party set off on 4 September and returned on 27 September, having covered 3,400 miles without physical or mechanical problems. Two of the Northern Italian POW camp sites were visited; Campo 17 Rezzanello, now a convent, and Campo 49 Fontenallato, now a children’s school, whilst on the journey south calls were made at the Assisi, Sangro and Cassino war cemeteries, all of which were beautifully tended.

The section of the Gustav Line in which the party was personally interested was in the central region near Castel di Sangro, north of Isernia and Campobasso. It was here that each had made his way through the German Line in late November or early December 1943 in Arctic conditions. This time all was bathed in sunshine and it was possible to explore at leisure the area traversed in darkness and with some difficulty 35 years previously. The superb scenery in the Apennines and the unfailing hospitality, friendliness and assistance afforded by the Italians combined to make the journey worthwhile in every sense. Camp sites such as those close to Mont Blanc in moonlight, overlooking Florence, in riverbeds, on the shores of the Adriatic and Mediterranean, and below Monastery Hill at Cassino have left indelible memories. Any

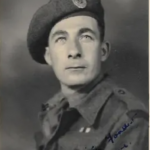

[Photograph with caption]: From left, G B Drayson., E T Hampson, K M Goddard, T D Forster.

[Photograph with caption]: Rezzanello, the castle in which the four were POWs.

doubts that might have existed regarding the ability of four veterans to live in confined quarters and in complete harmony after a gap of 35 years were quickly dispelled, no doubt helped by rubbers of bridge and liberal brandies with which most days ended.

Members of the party were Capt G B Drayson (Blazers), Maj T D Forster (Martinique). Maj K M Goddard (Blazers) and Ct E T Hampson (Blazers).

The four who undertook this nostalgic journey were well aware that others from the regiment had also completed the 500 mile trek in 1943. There were seven junior officers from 28th Field Regiment in the camp at Fontenallato when Italy capitulated and evacuated the camp before the nearby Germans had time to round up the POWs. The seven made their way into the hills, then split into smaller parties for easier concealment. All reached the Sangro river where Lt [letter unreadable in original] Mathieson (later Maj) made a successful crossing with Burnaby Drayson but unfortunately Capt H D Armstrong, the then Adjutant, and Lt Bill Reid (Blazers) were recaptured and spent the rest of the war in German POW camps.

28th Field Regiment was, prior to June 1942, on the British Indian establishment of two eight gun batteries of 25 prs. The batteries were numbered 1/5 and 3/57. A third battery was in process of formation in Cairo in June 1942 to be numbered 5/57 and around which the regiment was re-formed and took part in the battle at Alamein after tne Cauldron disaster. The regiment was then transferred to the Burma front, still with 5th Indian Division of which it was a part throughout the 1939-45 War, and was in action there with 1/3 and 5/57 Btys on VJ day. After their escape Forster, Goddard and Hampson were posted back to the regiment and although through some quirk in regulations the last named was judged to be too old for jungle warfare he feels he disproved this by going to Java and Sumatra after VJ day and completing our recent journey 35 years later!

[Digital page 3]

[Text added to original.] THE GUNNER 1979. For inclusion in archives. May 2009.

Inside Out!

by Major K M Goddard, late RA [Royal Artillery]

The experiences of two, from a party of seven, officers of the old 28th Field Regiment RA who were taken prisoner in the 1942 Cauldron Battle and, after 15 months in Italian POW camps, walked 500 miles to the River Sangro. The experiences of the other five were not dissimilar although two were recaptured when in sight of our lines.

News of the Allied landings in Sicily in the Summer of 1943 was received with great excitement by 600 British officers in Fontenallato POW Camp in Northern Italy.

The invasion of Southern Italy and overthrow of the Mussolini Government aroused high hopes that the Germans would retreat to the Alps. Our Italian Camp Commandant shared this view and approached the Senior British Officer with a proposal that he would call off the camp guards in exchange for safe conduct for him and his staff.

This was agreed and on 8 September we marched out in company formation to an area about two miles from the camp. Our orders were to remain as an organised group in order to facilitate matters upon the arrival of the Allies whom we were informed were expected to land at Genoa immediately. In the event matters took a distinctly different turn. The Germans were not prepared to give up any part of Italy without a struggle and within hours rumours reached us that an enemy armoured column was approaching the now deserted camp. The thought of being rounded up was too much and organised direction of events ceased.

Seven of us from the old 28th Field Regiment RA decided to set off in the direction of Genoa with the aim of getting into the Apennine mountains at the nearest point. It was late afternoon and as darkness fell we gained confidence. Our route crossed the main Milan — Rome road and railway and with every sound straining our nerves we were glad to get across. Apart from short halts to surmount obstacles or agree direction we carried on through the night and in the grey dawn reached the foothills of the Apennines.

We had no idea what the attitude of the Italians would be towards us but felt sure that those who remained sympathetic towards the Fascist regime would not only be a danger to us but would limit the freedom of action of others of their countrymen.

In the full light of day we felt uncomfortably conspicuous in battle dress from which we had removed the scarlet diamond patches which were our POW insignia. By common consent we agreed to separate into two pairs and a three unless anyone wished to travel alone. We pulled blades of grass of varying length, drew from them and accepted the result without question. After an interchange of good wishes we parted company at 30 minute intervals.

[Photograph with text caption] The Bardi Valley today.

[Map with text captions] MAP OF NORTHERN AND CENTRAL ITALY

MILAN – FONTENALLATO – PARMA – GENOA – BARDI VALLEY – SPEZIA – FUTA PASS – BOLOGNA – BORGO – LORENZO – SAN SEPOLCRO – GUBBIO – ASSISI – GRAN SASSO – AQUILA – RIVER SANGRO – ROME – OPI – VILLETA BARREA – CASSINO – NAPLES – SALERNO

[Caption] The dotted line shows the escape route taken.

My companion was Erik Hampson with whom I had left England in 1941. He was 33 and I was 26 years old. He was an experienced rock climber and we were both pretty fit. Although at the time we had no idea of our exact location we were in the Bardi Valley which contained, and still does, many families who for generations have sent sons and daughters to England to return in later life to end their days in their homeland. We could not have found a more hospitable community and we remain deeply in their debt. These were scattered homesteads and one such befriended us and by day we were concealed in a hilltop cave, coming down at night for a meal in the farmhouse and to sleep in an adjoining barn. Neither of us regarded this as more than a temporary arrangement and we were not thinking beyond each day. Our news came via our hosts and it quickly became evident that the Germans were not only occupying the area in force but were threatening the local population with the death penalty for sheltering Allied personnel.

We knew our presence to be an embarrassment and that these good people had to remain whilst we were free to go. Our faith in earlier reports of landings at Genoa weakened and, although we discussed the possibility of continuing in that direction and possibly securing a small boat, we did not pursue it. The other alternatives were Switzerland, some 100 miles north, or to go south with the knowledge that the 700 miles now separating us from our own forces would reduce daily.

We settled on the Southern route and to leave the following night. Our hosts provided us with civilian outfits, two sacks into which we put our few possessions including battle dress, with the thought that we would eventually wear this when we neared the German front line. Our Army boots we felt to be essential to the task ahead and they proved to be our most valuable asset.

It was by now the third week of September, the weather

[Digital page 4]

superb and plenty of fruit everywhere for the picking. With grateful thanks to our benefactors we set off now with a definite plan to follow the watershed of the Apennines which would keep us on course and away from concentrations of enemy activity. Progress by night had its problems, we were unable to fix landmarks and, when clouds obscured the stars, with strained eyes, stumbled over actual or imaginary obstacles. Daybreak would find us sometimes with no suitable hideout and having covered only a few miles. We had with us a small map of Italy torn from a school atlas and knew that we were nearing the Futa Pass on the Florence-Bologna road. So now again we began to move by day accepting the risks of being seen but knowing we could cover more ground. From a hillside we watched a German troop exercise and shortly after we hit the main highway which was taking considerable military traffic. When all appeared clear we slid down a bank on to the road and down a slope the other side into undergrowth. Hardly were we concealed than vehicles screeched to a halt on the road above and troops dismounted and spread out all around us calling to each other as they searched. Whether or not we were their target, so it seemed to us, and although after what seemed an age, they remounted and moved off, we remained paralysed for at least an hour until our nerves were steady.

Moving by day we followed a procedure of first enquiring of solitary labourers what lay ahead and if towards evening we learned that no Germans were in the next village, then we would approach an isolated farmhouse, ask for food, and an overnight stay in a barn. Such requests were sometimes met with refusal by menfolk but invariably they were overruled by the women whose maternal instincts seldom failed us. We had set ourselves the target of being home for Christmas and this simple aim kept us going when spirits flagged, weather worsened and we suffered setbacks or our stamina and nerves were overstretched. At the same time our ultimate goal was seldom in the forefront of our daily thoughts, which were concerned with evading the enemy, food and sleep.

On a number of occasions we were ejected during the night because of local alarms and once in the midst of a very good meal motorbikes roared to a halt outside and panic followed. The lights were extinguished, we made a dive for the door, and amid grunts and shouts as we collided with bodies, German or Italian we knew not, we were out into the night air and charged on until legs and lungs brought us to a halt with hearts pounding. Such experiences were always half expected and caused us to be in a constant state of readiness.

By late October in the high Apennines fruit and other produce which had been readily available during the harvest season became scarce and the weather deteriorated. Health had been no problem, but repeated soakings without change of clothing began to tell. One morning Erik found his legs seized by a form of rheumatism and was unable to move. Fortunately it lasted for only a day but the enforced rest revealed another problem. In POW camp we had plenty of experience of bedbugs and other vermin but were able to keep ourselves reasonably clean. Now to our horror, whilst drying and airing our clothes, we found lice and the fear of contracting some disease worried us more than a little.

In early November we reached the Gran Sasso which rises to over 9,000ft and the whole landscape was snow covered. We were not equipped for severe winter conditions but still felt that our best chance lay in keeping to the high regions. We heard increased reports of enemy movement and learned that the battle front was now on the River Sangro-Cassino line, less then 50 miles South. We met a group of partisans who took us to their hideout which was bristling with small arms; they were very disorganised and we felt no desire to stay with them. Then a villager pointed out a mountain cave where, he informed us, a number of our countrymen were hiding. We made our way up unchallenged and found within the small entrance a large cavern, thick with smoke from a wood fire, around which were eight or nine Britishers who had been there for about six weeks and one of whom was obviously very ill. Their intention was to remain there until the arrival of our forces, several of them having made unsuccessful attempts to get through the German line. That line remained unbroken for seven months and one wonders how these cave dwellers fared.

(To be concluded.)

[Second half of page is an advertisement. Text not transcribed]

[Digital page 5]

Inside Out! Part 2

by Major K M Goddard, late RA

The next day we moved on across a great plateau deep in snow and at one point saw what we thought to be a ski patrol of about seven men but they did not turn in our direction. We sheltered that night in a derelict farmhouse and the following morning continue in snow through a forest, containing large ammunition dumps, and saw a German motor cyclist on a lower road who was fully occupied in controlling his machine. We could hear gunfire and then the track we were on suddenly left the woods turning sharply and as we rounded the bend we were confronted by a party of German soldiers. We had no real option other than to continue if we were to avoid attracting attention and to our relief they appeared to take no notice of us. We then saw a group of wooden huts beyond which was a battery of guns all overlooked by a hilltop village. We made our way up to the village and found it to be clear of Germans but the Italian community was understandably apprehensive. One family put us into a hayloft and provided food and then, before dawn, wakened us from sound sleep with the news that the Germans were searching the village. We made a hasty exit scrambling down the rocky hillside, skirted some of the huts and got into trees on the snow covered slopes of the valley. As dawn came we could see the range of hills which we guessed must mark the front line and, as all activity appeared to be confined to the valley bottom, we plodded on until towards evening we came upon a shepherd’s hut which we were allowed to share for the night. He was killing and cooking meat as he required it. This we found somewhat rich after the almost meat free diet to which we had become accustomed. He also showed us his permit from the Germans which allowed him to tend to his flock, from which we gathered that civilians were banned from this area. We later found that the Germans had evacuated all civilians from villages forward of Opi, where we were the previous night, and nearby Villetta Barea.

The next morning we carried on along the hillside in sunshine, listening to intermittent gunfire and watching vehicle movement along the valley road. We felt like spectators of an event rather than participants and when we saw a group of about 20 figures moving below in our direction we did not immediately realise that we were their target. It was not until they began shooting that we reacted and beat a retreat into the trees where we hid in a small cave. The Germans showed no determination to follow up and probably assumed us to be local villagers who had been given a sufficient fright. We discussed our next move and decided that at nightfall we would descend at the point from which the Germans had approached, assuming this to be the most direct way to our lines. We followed this plan until we saw a fireglow and heard voices. Approaching as near as we could, we watched men come and go and considered whether we should risk walking through in the hope that we would go unchallenged. Our nerve failed and we decided to work our way round on the heights above. We should have realised that if the line was on the River Sangro, then the valley had to be crossed but logical thought was often absent and wishful thinking controlled our actions. We set off up the mountain side and at one point heard voices close to us in what was probably a German OP [Observation Post]. Then we moved higher on to ice, so hard that we could make no impression with iron shod boots. I lost my footing and tobogganed some distance, coming to rest in a depression. I was unhurt but an injury could have put paid to our chances and this prompted us to return to a lower level. It was by now approaching dawn and we were back where we started the previous night. In the grey light we saw huts around us similar to those near Opi and as we crouched beside one a mule passed us, presumably going up to the OP [Observation Post]. It was obvious we could not stay where we were and it was getting lighter all the time. We got up and ran in the general direction of some rocky outcrops we had seen the previous day and, having encountered nobody, we paused for breath and to take stock of the situation. From almost at our feet a figure rose, giving us a tremendous shock, but he proved to be a Free Frenchman who said he had been concealed there for several days but, because the area was so closely defended, he could find no way through. His morale was low and he asked to join us. Whilst we felt little inclination to increase our risks by additional company, sympathy won, and we agreed to let him tag on, and the three of us then made for an area which appeared to offer more cover. We were brought up sharply on the edge of a gorge which dropped almost vertically several hundred feet to the river. Now in a state of exhaustion, having had no real sleep for about three days and none at all during the previous 24 hours, we decided to make the descent. Showers of stones and boulders went crashing beneath us making a tremendous noise but we were more concerned with foot and hand holds than anything else. It was no easy task tired as we were, and then we became aware of the roar of the river below us which, as we descended between the walls of the gorge, became deafening and must have completely veiled the sound of the miniature avalanches we were causing. We had good reason to be thankful because to our dismay we now saw a small group of figures on the far side of the river. We were too high above to make out clearly who they were but we presumed them to be enemy. Rational thought should have persuaded us to go back up, traverse to a less conspicuous position, or stay on the cliff face until the end of the day, but exhaustion and desperation drove us on, accepting that recapture was almost inevitable. It was not a sound or sensible course and we should have summoned up sufficient courage and will power to act differently but down we went amidst further avalanches. At the bottom there was no cover and we found ourselves separated from a party of five German soldiers by the river torrent, some 30 feet across. They were outside a hut, one chopping wood, one cleaning a rifle and the other preparing food or similar tasks. We watched them for some moments unable to believe that we had not yet been seen; then as realisation dawned, we crouched and ran along the narrow track towards a bend expecting every moment to hear and feel shots but none came and we rounded the bend safely. To this day I believe the hand of Providence guided us that day and lowered a curtain between us and the enemy, enabling us to see them whilst they were unable to see us.

In front of us was a rock sangar, probably used by a shepherd, and on the floor were some empty tins and a small heap of husks. Although in distance we were less than 200 yards from the German hut, it was not in view, and we pushed our luck further by lighting a fire in order to have something hot to drink and eat and give a little warmth. We put the husks in water, boiled up a sort of porridge which we shared, and then slept for some hours. We awoke feeling cold with only the fire embers, but immediately discussed means of crossing the river torrent. Our plan was to strip naked, tie boots and clothing round our necks, and when across, to follow the track past the German hut in darkness and hope that this would lead us through their front positions. When darkness fell it really was black and the noise of the water seemed greater than ever. We tested the depth with long staves and found it to be about chest high. Using the staves as a link between us, Erik went first, then myself and the Frenchman last. The icy water was like an electric shock but it was the force which was more alarming. One slip and there would be no chance in the boiling stream of regaining a footing. When Erik was almost across the Frenchman slipped and grabbed me and had Erik not stood firm we might all have gone but with his help and the staves we made the far bank. We dressed where we stood. Erik and I

[Digital page 6]

now donning battle dress. We set off immediately, passed the German hut which was in darkness and started an uphill climb nothing like so precipitous as that which we had descended on the other side. In starlight above the gorge we crossed some open ground, then heard dogs barking, after which we thought we saw their silhouette. We flattened and froze feeling sure these would be guard dogs. The animals remained motionless and we thought they might be awaiting a move by us when, after an age, one moved slowly towards us and we saw it to be a Sheep. Breathing sighs of relief we carried on until we came to a wide river bed with shallow water which we crossed and came to a small railway station and an apparently deserted village. We stopped to listen and heard the crunch of boots and voices: then discerned a patrol column which passed a few yards from us, the last man with a cigarette glowing. It was all a patrol should not be and I hope it was not one of ours. We were still expecting to find some kind of continuous defended line so we were not prepared to treat any movement as other than German. Later we came across white tapes which we took to be night lines but again the question was — whose?

The sky had clouded and now rain began to fall and at first light we found ourselves in wooded country and again heard voices which we thought to be English but could not believe that we were beyond the German Lines. We sat at the edge of the woods concealed by bushes and watched shell bursts on the adjoining hillside, not knowing from whose guns, when the Frenchman jumped up and shouted ‘un Soldat Anglais’. Our first impulse was to shut the Frenchman up but we then saw, across some open ground, indisputably, a British soldier in battle dress with a steel helmet, webbing equipment, respirator and rifle. Without more ado we careered across the field shouting and waving as we went. What we must have looked like in our unshaven and bedraggled state I can’t think but we achieved surprise and the poor chap made no attempt to move or challenge us. We explained who we were and that he was the first of our countrymen on Allied soil we had spoken to for 18 months. He was a runner with the forward company of the Northamptonshires with the 5th British Division and he led us to his company HQ and the smell of breakfast cooking.

It was the morning of December 1st and we were home, if not dry.

The seven in the original party were: Capt H D Armstrong, Capt T D Forster, Capt G B Drayson, Lt G Mathieson, Lt E T Hampson, Lt W Reid and Lt K M Goddard.

END

[Second half of page details a story of Larkhill Adrenaventure 1978/1979. Text not transcribed.]