Summary

Ronald Dean had been captured many times as a prisoner of war. Dean was to find himself across Italy and Germany as both a prisoner and an escaped prisoner. He’d been held at L’Aquila Camp, the Prison Camp at Sulmona, Stalag 383 at Hohenfels, made to march with hundreds of other prisoners, and escaped near-death on numerous occasions.

In the lead up to his liberation by American soldiers, Dean had imagined his own death was certain, but the wavering Germany and radio telecommunications had led him to believe that his best option was to remain in the prisoner of war camp. Dean then emerged from “The Blue”.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital page 1]

[Cover page annotated with “Dean, Ronald. Out of the Blue. Ron Dean.]

OUT OF THE BLUE

RON DEAN

[Digital page 2]

[Note] Into Archives May 2006

Having appreciated the Australians in battle Dean uses an Australian expression for being lost in desert country. Like so many when Rommel appeared for the first time and not only stopped the Axis retreat but started to drive back the British, many including a group of high ranking officers were captured. (More by luck than judgement the 150 Field Ambulance of which this writer was a part got away.)

Dean was more fortunate than later prisoners and did not languish in POW [Prisoner of war] camps of bare sand surrounded by barbed wire but was taken via Benghazi and Tripoli to Naples and so in summer ’41 became one of the earlier inhabitants of the Prison Camp at Sulmona. There, as did a telegraph pole in another camp, an Italian ladder was quickly demolished as firewood for the blowers for cooking. A radio, smuggled in parts ensured that the POWs knew the news before their captors.

Knowing a head of an armistice the POWs were ready to go and to climb the steep Maiella which towered up to the east of the camp. Mostly when no Germans came, slithered back down to the camp. Dean and 5 others, however, go up and over further away and purchase a sheep from a helpful shepherd who directs them until they get to the remote village of Caramanico. They stay in the remote village of Caramanico with a very poor woman who had lost 3 sons in Africa. In crossing the Pescara River they almost bump into Germans and are taken in a house on the edge of Castel di Sangro. They are recaptured and taken by train to L’Aquilla and the train is bombed (See Stan Skinner). While fellow prisoners are killed and wounded, Dean and the others get away. With Albert from Nottingham and 3 others they hide in a cave and are provisioned by the Communist May of Acciano. Germans raid for food and men for working. In late January, he is recaptured and taken back to L’Aquila Camp. Dean contracts pneumonia and receives excellent treatment from the Germans, and by German patients – though there is further bombing.

He’s taken north with a German convoy past Verona. The POWs are dropped off and made to march, those who drop out are shot. Finally taken to Moosburg, east of Munich (with Dachau on the west.) they encountered Russians there (As did KK and learnt Russian from them). After so much bridge playing in Camp Dean never played again. Moved to Stalag 383 at Hohenfels they could hear via their radio the Americans approaching and the war collapsing. But they were marched out. By throwing a fit Dean was carried by two friends back to the hospital of the camp as thousands went into the Countryside. German guards came with them to forage for food for all. Not knowing what the camp was the Americans were ready to fire but saw the white sheet being flown. The Americans had seen the horrors of Dachau and were very trigger happy. One POW had found a horse and was riding westwards, additionally there was no petrol for a hidden Mercedes. Poles, released from slave labour were scrounging for food. Hitler youth were being captured. Finally a convoy of Americans lorries swept them off to an air strip at Nuremberg.

Captured 3 times Dean saw the best and the worst of the Italians, the Germans, the British, the American and even Russians.

[Digital page 3]

[Title page]

For you, the War is over, said the German soldier.

How wrong he was I was soon to discover.

Ron Dean, Essex.

Copyright 1999

Approx. 22,000 words

[Digital page 4]

Thanks to our companions in arms in 1940, the 6th Australian Division, leave in Cairo was more interesting than it might otherwise have been. To the diggers, the western desert was “the blue” – Australian slang for an argument or row, and the term was adopted universally.

[Digital page 5]

OUT OF THE BLUE

[Digital page 6]

Until the early Spring of 1941 the Allies progress in the Western desert was spectacular as Wavell’s 7th Armoured Division swept onwards from Benghazi.

Then, at El Agheila, 339 Battery ran into some stiff opposition in the shape of Rommel’s Afrika Korps.

The first indication of trouble was the Sergeant-Major touring the wagon-lines, where we were resting, and ordering everyone to pull back – or as he put it, “Every man for himself.”

It was at that moment, with the guns already coming back through our lines, that our 15cwt [hundredweight] truck refused to start. Not surprising really – most of our sparse equipment was clapped out after the long haul from Cairo.

Grabbing our packs, the four of us moved out on foot amid the dust stirred up by the headlong rush of vehicles all around.

We had not gone far before Sgt. [Sergeant] Stephens gun-tower pulled up and we gratefully climbed aboard.

With no room left inside, I had to travel for several miles perched on the bonnet before I could transfer to another vehicle heading east towards Derna.

Somehow, in the confusion, we were separated from the rest of the Battery and eventually arrived in Derna to give the garrison there the first news of the rout.

Nigel Strutt, who had lost an eye in an earlier battle, was there en route to re-join his troop, and automatically took charge of us stragglers.

According to his information our unit was at Mechili, an inland oasis reached by a rough desert track.

Next morning, with Stephen’s 25 pounder and crew to keep us company, we set out with Nigel in the lead.

After travelling for some while, we saw in the distance what our leader took to be an Australian vehicle.

Unfortunately, when he went forward to make contact it proved to be a well-armed German carrier whose crew captured us without a shot being fired.

We had no small arms to fight with in any case, and the best that Cliff Stephens could do was to take out the firing-pin

[Digital page 7]

from the 25 pounder and lose it in the sand.

We were not the only ones to be surprised by the swift movement of Rommel’s highly trained and very professional soldiers.

As we were gathered together with other unfortunates we discovered that General O’Connor, one of our best, had also been picked up, and George Judd from 339 Battery was there as well.

Unbeknown to us, Mechili had fallen after some fierce fighting and the whole front was extremely fluid.

Captain Judd saw an opportunity to make an early escape after asking his batman to keep a watch on his bedroll, and saying that he was going for a walk.

At Benghazi we were herded into a large building, which luckily was not close to the docks where the RAF [Royal Air Force] air force visited most nights with their bombers.

Our captors never ceased to say to us, “for you the war is over,” but nothing could have been further from the truth.

For me, it was just beginning – everything that had gone before was like being on manoeuvres, except that the dead bodies laying around were really dead.

Now, and for the next four years, my education would commence and be enhanced.

Although we didn’t stay long at Benghazi an elaborate escape plan was hatched to free O’Connor, but it came to nought, and like me he would have to wait until 1943 to be loose again.

Now in the care of Italian guards I learned an early lesson. Sleeping on a concrete floor on lice-infested straw some hundreds of us were surprised by an unexpected blanket issue.

Not nearly enough for a blanket per man, I was too slow off the mark and it was three days before another issue was made.

In the interim I shared a blanket with another soldier and had plenty of time to sharpen my wits in readiness for the painful exercise of survival. From Benghazi we were moved to Tripoli in open railway trucks, and once there entered a hell-hole of filth and disease that only the most resolute and fit could endure.

Fortunately, I wasn’t kept in the Tripoli cage for many weeks, but I was there long enough to see many of my compatriots die from dysentery, or wounds, or other illness.

Without warning we were suddenly moved from the camp to the

[Digital page 8]

docks and loaded onto an Italian ship.

Battened down in the dark holds, surrounded on all sides by bodies, vomit and excreta, it was certainly no pleasure cruise. From talking to the Italians guards we gathered that we were en route to mainland Italy, and the thought of sailing some seven hundred miles through sub-infested waters in a vessel flying the enemy tricolour didn’t make life any easier.

All idea of time was lost in those intolerable conditions, but I remember thinking that only a few months before I had been on leave in Cairo and had met a fakir outside the entrance to the zoo.

For a few coins he had read my fortune – drawing lines in the grubby sand and tossing dried bones at my feet.

What he told me about myself was remarkably accurate, and his parting statement had now come true.

“You will be out of the blue, leaving the desert in the next few weeks.”

At the time I had laughed my disbelief, but here I was, out on the briny, and praying that we would safely make landfall soon.

Eventually, the ship’s engines stopped, and as the vessel rocked to and fro in the swell, the hatch covers were lifted and we climbed out into bright sunshine to see the beautiful bay of Naples.

As we were herded ashore, crowds gathered to watch, some hissing and spitting, but mostly curious to see the enemy so close.

A short march distant a train was waiting for us in a siding – sumptuous carriages with delicate upholstery protected by snow-white antimacassars.

The first men to board hesitated for a second or two. Surely there was a mistake – the train was meant for royalty, not a bunch of grimy, travel-stained prisoners-of-war?

The guards waved them on and the rest of us followed. Rattling along through the splendid countryside we couldn’t believe our luck -what a contrast from the dirt and horrors of the desert and the claustrophobic confines of the ship’s hold?

The train drew into a small station, where in spite of the war, the signs read Capua, and we were told to alight.

[Digital page 9]

The place was well-painted, and everywhere flowers grew in abundance. Lost among the surging crowd of prisoners I saw an Italian with an ice-cream barrow sheltering under a gaudy sunshade. Even as I spotted him, an Australian got close, offered him an Italian note, and received an ice-cream cornet in exchange. The cornet was devoured before a guard noticed what was going on and swooped on the hokey-pokey man to tick him off. “The guy I got the note from didn’t need it anymore,” the Aussie muttered as he moved on, licking his creamy lips.

The camp at Capua turned out to be only a temporary one housing us in small, bivouac tents until we were moved on to permanent campi di concentramenti.

It rained every day I was there, and when I left with others some few days later the whole site was knee-deep in mud.

We were sent to Sulmona – Fonte d’Amore to be exact; one of the oldest camps in Italy, fifty or sixty miles north in the Abruzzi.

A large camp of walled compounds and military-style huts, Sulmona had been in use as a prison for many years.

Of our generation its early inmates were Albanians and Yugoslavs, but the compound in which I was placed held the crew of the submarine ‘Oswald’ whose Chief Petty Officer was the most senior NCO [Non commissioned officer].

He was subsequently replaced as camp leader when a more senior prisoner, a Sub-Conductor from the RASC [Royal Army Service Corps] arrived.

After my initiation as a POW in Benghazi I had managed to acquire an Italian officer’s silver-grey army blanket and had held onto it through thick and thin.

It was far superior to the standard issue to the lowly soldato and as soon as I entered the gates of Fonte d’Amore it was confiscated by the guards.

As I got two other blankets in exchange, I couldn’t complain. Without exception, everyone of the newcomers were lice-infested so the first priority was to get reasonably clean once again. In those early months and for the remainder of 1941 water, soap, clothing and food were in good supply, and apart from the frustration of being captive, life was bearable. Gradually, parcels of clothing were received from home, new uniform and food parcels came from the Red Cross, and books

[Digital page 10]

and board games and basic sports equipment became available.

The dreaded pidocchio was conquered with new clothing and frequent showers, and a loose, military-style system maintained common sense in the camp.

When I first arrived each man had a bed consisting of four wooden planks placed over two iron trestles, a rough mattress, and a couple of blankets.

Quite soon however, more and more prisoners arrived and the trestle beds were replaced by double bunk beds.

Wherever the wooden beds came from they brought with them their tenants of bed-bugs which became a pest almost as bad as the lice.

At the time, the Italians were making a generous issue of foul, black cigars which even the most ardent tobacco addict couldn’t tackle.

Then somebody hit on the idea of stewing the evil things, with the result that we then discovered the brew to be the perfect pesticide.

Cigarettes from home started to come in, although some luckless individuals found that their personal parcel sometimes contained just empty packets and a bit of wood to simulate the weight.

Very few prisoners actually smoked cigarettes, however, they were much too valuable as camp currency – as were soap and sugar.

A barber was allowed to set up business in the compound and offered a short back and sides for a single cigarette.

He was probably the only one of us who could afford to smoke. It is often said that necessity is the mother of invention, and nowhere is this more apparent than in a prisoner-of-war camp.

With little else to do – other than the occasional work party helping to dig out a promised football pitch, alert minds turned to a variety of exercises. Many of the inmates had all manner of professional skills and these were put to good use.

Everyone believed that the so-called pitch would be a parade ground for the Italians, so it took some three years to construct. Early on, escape tunnels had been started and an Australian mining engineer had designed and built a perfect air-pumping

[Digital page 11]

system from old tin cans which was capable of supplying fresh air over a distance of some sixty feet.

Artificial limbs, suitcases, thermos-type coffee pots, musical instruments, dartboards, and home-made wine were just a few of the items that genius, time and patience produced from odds and ends.

Sometime in 1942 there must have been a change in policy affecting POWs – the quantity of food sent into the camp each day was reduced, water was rationed, and bright red patches were sewn onto our battle dress uniforms. In my compound, raw food such as macaroni, vegetable and occasionally indifferent meat was pooled to produce a watery soup once a day made by prisoner cooks.

The sergeants, who occupied one hut, had a similar arrangement. Soup was supplemented by a small bread roll per man, and more often than not, this was the only food to be had.

Under the Geneva Convention every man should have received a Red Cross food parcel every week, but bombing raids, transit delays, pilferage, etc. all took their toll and weeks would go by without an issue being made. Frequently, there were only enough parcels for one to six men and dividing them fairly was a work of art.

Other than the daily communal soup, every man did his own cooking, or was part of a small group pooling their assets. Tea was brewed constantly, the tea-leaves being used so often that they became white.

Volunteering for the occasional work-party could produce a scrounged turnip or onion, or better still, wood.

Fuel, anything that would burn was in short supply, so individual cooking fires had to be efficient and economical.

Interestingly, the finest stove that evolved, “the Blower” appeared in both Italy and Germany, constructed to much the same design and able to heat a can of water in less than a minute.

[Diagram of “the Blower” stove]

[Digital page 12]

On one occasion, two Italian workmen came into the compound to repair a roof and were both stupid enough to go up the wooden ladder one after the other and disappear across the roof-top.

At least a hundred watching prisoners pounced on the ladder and within a few minutes it was broken into manageable pieces and safely hidden. Eventually, the guards heard the cries of the unfortunate workmen and came to their rescue.

After an unsuccessful search for the ladder, Flatfoot, an unpopular Italian officer, punished us with extra roll-calls and redoubled his efforts to find home-made knives and other illicit possessions.

For a while, a camp commandant who was reasonably human took charge and was persuaded to allow an empty hut to be turned into a camp theatre. A Yugoslav artist and others scrounged paint and decorated the walls, using the theme, “Prisoners Through the Ages”. Some worked to produce a stage, or props, or costumes, and someone prepared scripts from memory – “The Monkey’s Paw”, “George & Margaret”, “Blythe Spirit”, are examples of what was produced.

One unfortunate portrayed a female so well that he became the most popular person in the compound and insisted on wearing female attire even when off stage.

He was eventually sent to another camp for his own safety. Everyone, including the Italian guards off duty enjoyed the shows, but they came to an abrupt end when a fresh intake of prisoners had to have the spare hut.

The Swedish Ambassador made an unexpected visit, and so did the Papal Annunzio.

A number of Roman Catholics got to kiss the Holy Ring that he wore, and presumably, it gave them some spiritual uplift. On a more positive note, they were directly responsible for a start to be made to repatriate the most severely wounded.

The first reaction to this news was that nearly everyone plotted to see if he could get himself in front of a medical board, but of course, short of chopping off either an arm or a leg, they hadn’t a hope.

In any case, nobody wanted to prejudice the chances of genuine applicants.

[Digital page 13]

Another benefit arising from these visits was that the authorities were persuaded to regularly take out parties of prisoners under guard for walks in the countryside.

We were required to march in an orderly fashion and to give parole that there would be no attempts to escape.

The trips out through the gates were a tonic, and of course, they provided a little local geography for those planning to eventually abscond.

Sulmona, with its high walls and thick, barbed wire fences was virtually escape-proof, although in my time there several made the attempt.

The most notorious was a man called Pledger.

On one occasion a troop of Italian artillery on exercise pulled into the camp and stayed the night in a compound close to ours.

Somehow, Pledger got over the wall during the night and curled up inside an empty gun-limber.

By sheer bad luck he was spotted next morning before the troop moved out.

Pledger tried unsuccessfully so many times that at the daily head-count, if the Italian sergeant-major couldn’t get his sums right, the cry immediately went up for ‘Pledger’.

Communication between the various compounds was difficult, usually notes being tossed over the wall when the guard in the watch-tower wasn’t looking to exchange important news with our immediate neighbours.

For a time a captured French patrol was lodged in the camp and was allowed to keep their Alsatian dog.

A magnificent animal, it had the run of the camp – the guard at the compound gate letting it in and out again as it wished.

For a long while the guards never suspected that the dog carried messages under its collar,but when this was discovered, the poor creature was shot out of hand.

Working-parties were never very onerous, which was just as well, for by 1942 everyone was down to a fraction of his normal weight.

Calculated scrounging by the cook-house staff whose job it was to collect the meagre daily rations from the Italians, managed on most days to get a little extra which was given to the day’s working-party.

[Digital page 14]

This usually amounted to little more than a cupful of soup per man, but every little helped.

Better still, were the efforts of the bread-collection party – four men and a blanket.

The men were required to hold onto the corners of the blanket while the Italian cook heaped in a specified weight of loaves. He was always too busy watching the weight to notice that under cover of the blanket one of the prisoners held a foot under the scale platform.

Our compound got away with this scam for many months, each hut in turn getting the extra daily rolls.

Probably the hardest work we were required to do was the construction of the football pitch.

This had been started by other internees sometime in 1940 and was being dug out from a rock and soil face about six feet high.

Whether you worked with a pick, or shovel, or trundled a wheelbarrow, it was equally hard going on next to no food, and progress was painfully slow. Everyone was convinced that it was going to be an Italian parade-ground, in any case, so it was sabotaged whenever possible.

Occasionally, a bored guard would lay down his rifle and seize on a pick to show how the job should be done.

This was always a signal for the prisoners to stop work and to cheer him on.

By 1943 some of the guards were well and truly hooked on English cigarettes and the contents of Red Cross parcels that cigarettes could buy – coffee, chocolate, sugar.

Many forbidden articles now came into the camp this way, including the parts to build a radio receiver which enabled us to get the world service news bulletins.

One escape tunnel had defied detection and slowly and painfully had reached the dirt road that went around the camp just inside the outermost barbed-wire fencing.

At the time, it had rained heavily for several days, so it was hardly surprising that an Italian horse and cart used for transport inside the camp should fall into our excavations. The war news that we were getting was much brighter, so any further tunnel attempts were shelved.

Whenever we received an issue of food parcels, by now an

[Digital page 15]

infrequent event, the guards had instructions to puncture all tins with a bayonet before handing the prisoner his cardboard box of goodies.

Why it was done we never knew, and certainly, tins would not have been hoarded to provide escape food.

Waiting in line for our parcels, we watched in breathless excitement for a certain brand of meatloaf to appear on the table in front of the guard.

In most cases, the contents of this particular tin were rotten and as soon as the poor, unfortunate plunged his bayonet in he was covered with an evil-smelling fountain of putrid meat. Prisoner to prisoner justice was hard – a lesson that some had to painfully learn.

Anyone caught stealing from his comrades was usually forced to run the gauntlet of the whole compound who turned out in force to beat him as he ran.

Men who neglected to wash were forcibly scrubbed.

Tragedy sometimes struck when least expected. A letter from home with bad news – a death, a wife’s desertion, or no letters at all, were very often the thin line between carrying on with hope of killing oneself.

Homosexuality in the camp was rare, which is not surprising, for at that time it was not tolerated in the armed forces under any circumstances. Fellow-prisoner medical orderlies did what they could for the sick with only the very basic medicines at their disposal. An aching tooth would be extracted without any form of anaesthetic – the suffering patient being held down by force of numbers.

A small wound needing a stitch or two would be closed with ordinary needle and cotton sterilised in boiling water. Fortunately, nothing serious in the way of illness ever struck the camp.

Unexpectedly, a party of Japanese officers arrived one day, and the prisoners shivered from something more than the cold. However, nothing came of the visit other than an exhortation to volunteer to work in factories, and to fill in a form detailing what work we had done in civvy life.

The number of coronation programme sellers, hangmen, and bank robbers must have amazed the authorities, for nothing further was heard as the months dragged by.

[Digital page 16]

Somehow, news of the setbacks in the Western Desert, the fall of Singapore, and other debacles, were heard of and talked about with dismay.

The stubborn and gallant Russian stand at the Red October factory filled us all with the greatest admiration – then, for the first time Allied bombers were seen and heard overhead as they lumbered towards their targets.

Quite suddenly the collapse came.

First, the news on the radio, then the Italian commandant formally handing over the camp to the Senior British Officer. It was September 1943, and almost to a man, the Italian guards gratefully left us and went home.

This new situation called for some firm action to be taken, for at that stage, it would have been undesirable to allow hundreds of ex-prisoners to swarm at will over the surrounding countryside.

It was decided, and ordered, that everyone would stay put for a few days to await developments.

As a precaution, the wire fences were breached in several places and the main gates were removed, and look-outs were posted.

Fortunately, the camp was at the end of a long valley and the approach road could be seen winding off into the distance for a long way.

I recall that the weather was glorious, a perfect autumn, and all around us the trees and vines were bursting with fruit.

As the first hours of freedom went by, small groups of men sauntered back and forth through the wire just for the novelty of being able to do so without the risk of being shot. We helped ourselves to grapes and figs and peaches, and some wandered to nearby hamlets to trade for eggs – something that we hadn’t seen for years.

After three days of this idyll, the officers realised however, that the men couldn’t be held back indefinitely and many were already planning to move out to meet up with the Allied forces, wherever they might be.

At this time the radio was of little use as there was a security blackout over whatever was happening.

Rumours abound, including one that there had been a landing near Pescara.

[Digital page 17]

The wisdom of posting look-outs in the sentry towers was justified sooner than most expected when one afternoon a cry went up that a column of transport was approaching. Field-glasses were trained on the distant dust cloud and it was quickly established that the vehicles were German troop-carriers and motorcycles.

There was no possibility of successfully defending the camp against our visitors so the order was given to get out and up into the hills immediately. Within minutes, those who had been on the point of leaving in any case were swarming out through the wire.

The wise travelled light, taking just the bare essentials. Others took an assortment of possessions which they quickly abandoned as the going got rough – soon, the signs of their passing were littered all over the lower foothills.

The approaching Germans must have seen what was happening for they sent forward a number of light, armoured vehicles which raced ahead and opened fire on the last prisoners to leave the camp.

I had packed a marching bag on the day that the surrender was announced – a blanket, a little dried food, and cigarettes, and was among the first to get moving.

With two companions, I was well out of range before the enemy finally closed in.

We paused for a rest after the strenuous climb up the steep, rocky path, and well concealed in the undergrowth, we looked down on the camp below.

Here and there, prisoners were being herded back inside, and in one compound, a sizeable number of men were sitting on the ground under the watchful eyes of heavily-armed German soldiers.

All over the hillside, little knots of men could be seen climbing, but the Germans made no move to follow or shoot at them.

After a short rest we moved on again and caught up with another party of ex-prisoners.

They told us that there were about a hundred others nearby who were planning to spend the night on a grassy plateau in the shelter of the trees. This seemed sensible, as by now, it was beginning to get dusk

[Digital page 18]

and there was no point in wandering about aimlessly in the dark.

We came to a clearing, and although darkness was approaching fast, we could see groups of men all around preparing to make themselves reasonably comfortable until daylight.

A fire flickered from the entrance to a cave, and close by, a herd of sheep huddled together under the watchful eye of a dog and his master.

Talking to the shepherd was a British officer, and joining them, we discovered that the sale of half a dozen of the animals was being negotiated.

I made a careful mental note of the proceedings for future reference as the officer wrote on a piece of paper that the Italian, whatever his name was, sheltered us, and provided the sheep, and would expect to be paid by the Allied authorities on production of the signed chit.

Nobody mentioned of course that if the paper got into the wrong hands the luckless shepherd would no doubt be shot.

The sheep were duly slaughtered and roasted over an open fire, and provided us all with a good meal.

Although I was tired after the day’s excitement, for some unknown reason I couldn’t settle down.

I wandered around the site talking to various people, and eventually met up again with the officer who had got us the sheep.

He was discussing the possibility of carrying on that night over the mountain ridge, east to Pescara, and said that the shepherd would be willing to take a small party to the summit.

I asked if I could join him, and it was decided that six of us would move on within the next half hour.

We were warned that the journey would be tough and that we would need to be fit to stay the course.

If anyone dropped back he would have to be left to his own devices.

We left the others mostly sleeping and struggled on and up for what seemed an eternity, clutching at precarious hand-holds, slipping and sliding and crawling in our efforts to reach the top.

For the Italian, born to the mountains, it was no more than

[Digital page 19]

a stroll in his backyard, but we were sick with fatigue and anxiety, and dizzy with the unaccustomed altitude.

Every now and again he would urge us on with cries of “Avanti, andiamo, avanti”, but we were too breathless to respond, even rudely.

At long last, when we had nearly given up, came his cry of “La cima, la cima”, and we knew that the top was near.

The summit levelled out and we gazed down into the new valley, seeing in the bright moonlight the fold on fold of the hills beyond.

Bidding us farewell and a safe journey, the shepherd melted back into the night, back down the route we had painfully climbed, and left us to sleep where we lay.

Although we were high up it wasn’t yet too cold to sleep, and the sun was high when we next awoke.

Moving down into the shelter of thick trees we were able to light a fire that wouldn’t be seen and we soon had a hot drink brewing.

We estimated that we were probably only sixty kilometres from Pescara, but six of us in British uniform was too big a party to travel together.

So, three of us stayed back for an hour whilst the others moved on, quickly disappearing from our view along a track that appeared to lead eastwards to the lower foothills.

Unknown to us at the time, some miles away on the other side of the mountain, those we had left behind were also on the move.

German troops from the prison-camp had climbed into the hills under the cover of darkness and recaptured the escaped prisoners as they slept beside the shepherd’s cave.

[Digital page 20]

LOOSE IN THE ABRUZZI

[Digital page 21]

Some while after they left us, we followed our late companions slowly down the track into the new valley, checking by the sun that we were generally heading east. Somewhere on the lower levels they must have branched off, for we never saw them again.

For that matter, we never saw anyone else either, until after some hours we found that the mountain path ended in a small huddle of rural houses.

Just outside the hamlet we came across a man tending his vines who looked somewhat apprehensive as we approached. Looking at our uniforms, he asked if we were German, and when I said, “No, we were British ex-POW”. He became quite excited and launched into colloquial Italian much too quickly for me to follow.

“Are there any Tedeschi in this area?” I queried.

He assured us that the Germans never came to the village, and that was why our sudden arrival had surprised him. There was no roadway serving the houses, and the nearest the Germans came was to Caramaico which was about ten kilometres distant.

As we talked, several women came out from the nearby houses and offered us bread and sweetcorn, figs and grapes.

The little knot of villagers grew steadily and soon we were joined by a man who claimed to speak English.

Georgio, we discovered had been home on leave after working in America for some years.

Unfortunately for him, Mussolini declared war before he could go back to the States and he had been “on the run” since 1940.

Sale Nuovo was quite safe he assured us and we could stay with him for a few days if we wished.

In fact, we were anxious to get on, so we only stayed one night during which time our host tried to persuade us to exchange our uniforms for some tatty trousers and jackets that he had on hand.

His argument that we wouldn’t get far in battledress was valid, but ours, that we would most likely be shot if caught in civvies, was even stronger. So we declined his offer.

The next day we set out for Caramanico, keeping away from the

[Digital page 22]

main roads and moving across country as far as possible. Just short of the town, which from a distance seemed to be sizeable, we stopped to talk to some women gathering grapes from a vineyard.

After sampling some of the crop we were invited by the farmer to help with the harvest, and I suppose, with hindsight, that this was the first of several serious errors that we made in those heady days, when we said we would stay.

Pasquale, the farmer made us so welcome that we stayed far longer than we should have done, enjoying the harvesting as much as the company of the womenfolk, and sleeping securely in a dry out-building.

On one occasion, Pasquale persuaded me to go with him into the town and provided me with an ancient, black suit and an umbrella as suitable garb for the occasion.

After one or two minor purchases, we went into a bar for a glass of wine and I tasted Marsala for the first time.

Nobody in the crowded room took the slightest notice of me, beyond exchanging pleasantries in Italian, but of course they knew that I was English.

As we came back onto the street again, I nearly froze as a German truck passed within yards of me, and my host hissed, “Keep walking”.

I was more than glad to reach the comparative safety of the farm once more and to sit and enjoy the pasta that awaited our arrival.

Twenty-four hours later, Pasquale came to us where we were working in the vineyard to tell us anxiously that he had word that the Germans were searching for ex-prisoners in the town and that we should leave immediately.

His wife had kindly packed us some food, and he suggested that

[Digital page 23]

for the time being at least, we kept on the rusty, brown coats that we had been working in.

Even as we talked, we heard shots coming from the direction of Caramaico – there was no time to lose, as we quickly said goodbye and thanked the farmer for his help.

In our haste to get away from the area we stayed in flat countryside, although we soon realised that we were travelling west.

Eventually, we came to Popoli, a largish town built on several levels, and as we later discovered, a German garrison town. We walked into the lower part and came across some women washing clothes at a fountain who warned us that it would be dangerous to stay, although one old woman dressed in black caught hold of my arm, saying “Don’t be afraid, come with me.” “No, no, Maria,” Others protested, but the old dear wouldn’t be discouraged.

We were worried that the commotion would draw attention to our arrival so we thought it best to agree to go with the woman who lead us down a long flight of stone steps into a labyrinth of ancient houses and narrow passages.

On the way, Maria explained that the Germans seldom came to this part of the town, and if they did, we would get early warning.

She also told us that there were at least twenty other ex-prisoners living in the town.

Eventually we came to her home which was very poor but spotlessly clean, and she showed us a room with a plank bed where we could sleep.

During the period that we stayed, sharing her meagre stock of food, other women called in to say that we should soon move

[Digital page 24]

on as we were putting Maria in danger, and she was mad, anyway. Apparently, she had three sons, all of them had been killed in North Africa and now she was quite alone.

Perhaps that was why she had seemingly adopted us – if we went out to contact other escapees, she would follow us closely through the tortuous alleys that were the lower part of the town.

Sometimes at night we would brush shoulders with unarmed Germans looking for wine or women, but there was no curfew in the town and we were never challenged.

Occasionally, word would come that armed troops were coming to the area to search, then, with others, we would be concealed in a hidden cellar of a nearby house.

All of the houses in lower town had at least three exits onto different levels, so that the place resembled a rabbit warren – for which we were often grateful.

At other times, we would be hidden in a cave near the fountain and under a waterfall whilst we waited for the signal that the enemy troops had departed.

We were now into November and we had to decide whether to risk wintering in Popoli or take the mountain route south over the 9000 feet high Maiella before it became impassable until the Spring.

Our efforts to get the services of a guide came to nothing, and eventually we decided to just go very early one morning without telling Maria for she would have made a terrible fuss.

We left her a note and a couple of tins of corned beef that we had carried out of Sulmona.

By mid-morning we had reached the large cross that overlooks

[Digital page 25]

the town and which can be seen from a long distance.

It was much bigger than we had imagined and had a refuge hut built into its base.

As it was just the sort of place that a German patrol would be likely to check on we didn’t stay around, and by mid-afternoon we were high up the side of the mountain.

Since leaving Popoli we had only seen one other person, a woodcutter who had put us onto a track that would take us up to and over the summit.

The going was rough, but not impossible for determined men. We slipped and fell frequently, then stopped to rest and to look down on the road that snaked through the valley. Vehicles moved to and fro looking like dinky toys, and the sound floated up to us in the quiet stillness of the mountain.

I looked towards the snowline that we had to cross before dark,and rubbed my eyes in disbelief.

Unconnected objects appeared to be moving across the snow, and it was a few seconds before I realised that what I was seeing were the backpacks and equipment of a ski patrol dressed all in white.

We froze where we were, watching them about half a mile distant, then, as suddenly as they appeared they were gone, skiing smartly down and away from our sight.

Our struggle through the snow took up the rest of the day and it was almost night before we got to the top and started the descent on the other side. There was just enough light to see the roll after roll of hills spread before us, stretching as far as the eye could see.

We were now back into wooded mountainside but it would have been madness to have continued in the dark.

Huddled together for some warmth, we rested and waited for the moon to rise so that we could continue our march in some degree of safety.

I expect we dozed, but it didn’t seem long before a watery moon came up and we were able to resume our journey.

By sheer good fortune we stumbled upon a track and shortly after, one of those crude but welcome huts that abound in the mountains.

[Digital page 26]

It was unoccupied, except for a pile of chopped wood and some evil-smelling sheepskins, but for us it was a four-star hotel.

In high spirits after a few hours refreshing sleep, we took our time to reach the floor of the valley, carefully watching out for any activity along the road that we had to cross. It was fairly busy with troop movement, but it cut through the treeline so we would have good cover.

From the security of the trees we waited and listened for approaching vehicles.

There must have been something going on, for tanks on transporters and heavy support vehicles were coming through in large numbers.

Our immediate problem was the other side of the road, where there was a wall about four feet high for as far as we could see.

Tackling it one at a time we eventually got over, but it was only achieved with some difficulty and apprehension.

Later that day we met an Italian who not only offered to let us sleep in an outhouse, but said that he would take us to a part of the river where it would be safe to cross.

We must have slept soundly that night for none of us heard whoever came into the barn during the night to rifle our meagre belongings.

I had a service leather belt which I had taken off and put in my small sack, and one of my companions had a knife that he didn’t want to lose, but both were missing when we awoke next morning.

In view of the help that we were receiving we considered it prudent not to mention these losses to our host.

Nonetheless, we set out with him for the river very much on our guard. After a while we came to a spot where we could see a railway line in the distance, and beyond that the silvery gleam of a river.

Our guide pointed to some trees on the far riverbank and said there was the place to cross.

We thanked him, and he left us to continue onwards.

We reached the river without incident and after casting up and down for a short way, discovered a flimsy brushwood dam

[Digital page 27]

which stretched across the thirty feet or so of water. Gingerly, we made our way across, stepping on the frail structure and expecting to pitch into the river at any moment.

Once on the other side, we had to cross a minor road and some open country, and then we were safe among the trees once again.

Moving steadily forward, and fortunately not talking, we suddenly heard an unmistakable German voice say, “Ein moment, bitte.”

We froze where we were and saw less than twenty yards away two German soldiers stripped to the waist and digging defence trenches.

To right and left, others were digging in field guns and tanks, and we had very nearly blundered into the midst of them.

Slowly and very carefully we backed off, and then when we were sure that they hadn’t seen us, we turned and ran like hares back across the road, over the shaky dam, and kept on running.

After the best part of a mile we stopped to regain breath and to decide what to do next.

Our first thoughts, when we had recovered our composure, were that the Italian had deliberately sent us into the arms of the enemy, but of course, for all the conjecturing, we couldn’t know.

We walked in a wide arc for some while and until we thought it safe to reach the riverside once more.

In the distance was a small town and a bridge over the river, but as we got closer we saw that the crossing was guarded by armed soldiers.

There was no point in getting closer, we had to cross where we were or not at all.

At this point the Sangro was about twenty paces wide and there was no way of telling how deep it might be.

It was November, and the prospect of wading and swimming across was not appealing, but there was little choice if we were to get closer to the front line.

As luck would have it, the water wasn’t very deep, and we reached the opposite bank unseen or so we thought.

We crawled into a culvert under the road that ran alongside

[Digital page 28]

the river, and had stripped off our sodden clothing and started to wring it out, when we were surprised by a female voice from above asking why we had come across through the water.

The situation was so bizarre that we fell about, laughing, clutching our damp and naked genitals in false modesty. This was just as well, for a few moments later the owner of the voice came down into the culvert and proved to be an Italian woman of about thirty something.

We told her that we were English – escaped POWs, and she immediately offered to help us, notwithstanding Rio de Sangro was full of German troops.

She said that there were other Brits in the town being hidden by her friends and that she would take us home to dry out and have a meal.

Her offer seemed to be a reasonable risk to take as we put on the rest of our wet uniform, but the woman herself clinched it when she told us that our patrols were now regularly seen about four or five kilometres distant.

We set off into the town with our new guide, meeting several people on the way, but nobody seemed to take much notice of us and we were soon inside sitting by a fire, drying clothing. Other women began calling in and a bottle of wine was opened while a meal was prepared.

It was going to be quite a party, but then a young Italian girl called in and told us that we were in a hazardous situation – there were fascists also in the town, and they wouldn’t hesitate to betray us all.

She left, saying that she would go and arrange for us to be taken somewhere safer.

Almost within minutes of her leaving, one of the women upstairs suddenly called out in alarm, “Tedeschi, Tedeschi”, but the warning was too late, we were surrounded.

We thought that we might get out over the roofs, but a quick check, ruled this out.

Then the woman who had taken us in said there was a place in the cellar where we might be able to hide.

Hastily grabbing the rest of our uniform, we followed her down the stairs. The cellar was dark and full of straw and vegetables.

A broken down wall had a hole through which we could squeeze

[Digital page 29]

into a space under the open stairs.

We forced ourselves into the cavity and the Italian woman went back upstairs.

We heard the Germans hammering on the door, and then the sound of their heavy boots as they tramped through the house above our heads.

Occasionally came the sound of shouting and screams from the frightened women, and the sound of doors being slammed and furniture being moved. Finally, the door at the top of the stairway to the cellar was thrown open and a German voice called loudly for a light. Getting no immediate response, the trooper flicked on a cigarette lighter and for a brief second I could see his shadow thrown grotesquely against the dirty wall of the building.

He advanced slowly down the steps, lighter in one hand and pistol in the other.

He turned into the cellar and holding the lighter high, cautiously looked around.

Another step forward,and the tiny flame went out.

He cursed – strong Germanic swearing, and all the while the outline of his shadowy figure came and went as the wheel sparked the flint.

We held our breath, hoping that if the lighter failed to ignite again that the soldier would give up and go away to report that he had drawn a blank.

Then, it happened.

The wick was fired and in the resulting light the man saw the hideaway beneath the stairs.

He came closer, and in the next instant I felt the muzzle of his pistol held close to my head,

“Ach, so”, he cried, “Raus, Raus,”

Yelling loudly for his companions to join him, he clumped me over the ear with his gun and commenced to haul us out into the open.

The others soon arrived from above and we were pushed and manhandled into the street and thrown up against a wall.

“Christ!” Someone groaned, “they’re going to shoot us.”

It certainly looked that way for a few nasty moments, but then an officer appeared and rattled off a string of orders.

[Digital page 30]

The squad split into two groups and one lot went off to fetch the women from the house, whilst the remainder marched us to their headquarters about half a mile away.

The officer who interrogated us was at first certain we were spies, particularly when the woman who had denounced us claimed that she had seen us go into the house wearing civilian clothes.

We strongly denied this, thankful that for the most part our sorry-looking clothing was khaki uniform.

We insisted that we had forced our way into the Italian woman’s home, demanding food and shelter, and finally the German seemed convinced.

The following day, we were told that we would be taken to a prisoner-of-war camp, and shortly, a German corporal and three soldiers armed with machine-pistols came to collect us.

We stopped once on the journey for the Gefreiter in charge of the party to point out a hill in the near distance that the Allies regularly patrolled.

“Arrogant, Kraut bastard,” I thought vehemently.

“I hope they soon blow your bloody head off.”

Eventually we arrived at Castel di Sangro, but not at a prison camp.

The Germans had taken over a filthy, disused abattoir and were using it to hold a few re-captured prisoners.

As a gaol it wasn’t very secure, and in ordinary circumstances it would not have held any of us for very long.

For the moment however, we were tired and dispirited – oblivious of the sordid surroundings and the flea-ridden straw that served as bedding.

Escape was the last thing on our minds.

[Digital page 31]

THE PRISON TRAIN

[Digital page 32]

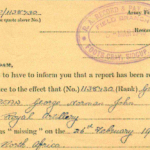

Towards the end of November 1943 several hundred re-captured prisoners-of-war of all nationalities were lodged in a transit camp at L’Aquila in central Italy awaiting transportation to Germany.

After my escape in early September from the well-established camp at Sulmona I had been re-captured trying to cross the River Sangro, some four or five kilometres from the Allied forward positions at that time.

Thus, I was a comparatively new boy in L’Aquila when the order came that we would be moving out within twenty-four hours. Carefully hatched escape plans were hastily abandoned as groups of men plotted how best to take advantage of the impending new situation.

For some, train-jumping was not a new experience and hopefully they counted the hours to being free again.

Usually, nothing much was needed to get out of a cattle truck – a piece of carefully honed steel with which to hack a hole in the wooden floor, or force open a door, and then a leap into darkness when the moment was judged to be right.

Many planned to get as far north as possible, perhaps near Bolzano where once clear of the train they could head for Switzerland.

Like me, most had been loose in the countryside since September and possessed nothing more than the clothes they stood in, so no time was lost in packing for the journey.

Soon, we were mustered, and heavily guarded by German troops marched out of the camp towards the railway.

Spirits were high, and it wasn’t long before we were singing lustily, belting out the prisoners’ favourite marching-song. Colonel Bogey, for the benefit of all and sundry.

Eventually, we entered an immense marshalling yard, far larger than most had expected to see, and then for some unknown reason shuffled into rough, alphabetical order.

We were searched for homemade knives, etc., and many were confiscated, although I am sure just as many eluded the search.

The entire area was full of goods wagons, many obviously loaded with war material.

[Digital page 33]

In the winter of 1943 such valuable cargoes could only move with any degree of safety after nightfall when the Allied air force was not so active.

Once the searching was completed the prisoners were quickly hustled into a line of empty goods wagons in batches of fifty.

As we climbed up into the trucks we noticed in dismay that strands of barbed wire had been nailed across the slatted ventilators.

The guards quickly closed the doors on the heels of the last man in and fastened the bolts on the outside.

It was now difficult to see what was going on in the railway yard as the two small vents afforded only a limited view for one man.

Our captors had thoughtfully provided a generous layer of straw for the floor of the wagon and we settled down as comfortably as possible in the cramped conditions, reflecting bitterly that we might have to eat the bedding before the trip was over.

On the positive side, we soon discovered that the floor was wooden and an immediate start was made to chip a hole in the floorboard.

After about an hour of silent chipping we clearly heard the drone of approaching aircraft and almost immediately the sirens sounded in the town.

Looking skywards through a ventilator, one of the prisoners reported seeing the bombers, silver and glinting in the sunlight.

Then we heard the whistle of bombs coming down.

One on top of another, fifty men tried to fall flat, cursing and praying as the first sticks of death arrived and exploded. Tossed about like peas in a pot, we were flung in all directions as the wagon leaped crazily off the rails with the violence of the assault.

More bombs arrived in the wake of the first salvo and smoke filled our lungs as fire roared through the roof at one end of our prison.

All around, the air was filled with the cries of the wounded, the crackle and rush of flames, and the explosion of ammunition. I struggled to my knees, clawing through the tangle of bodies

[Digital page 34]

and knowing that some wouldn’t rise again.

The wagon was leaning drunkenly on its side, still held by a coupling, and a corner of the roof and some of the straw were well alight.

At the other end a large hole had been blasted where the ventilator had once been.

For a moment there was panic as men surged towards the splintered gap and fought to get out into the open, but years of military discipline soon prevailed and an orderly escape began.

As the first ones out dropped to the ground there were cries from those still inside, “open the door, open the bloody door,” but in spite of these appeals the doors remained shut fast.

In my turn I took a header through the hole – not too soon, for by then the fire around us was becoming unbearable.

The drop to the ground was quite considerable, five or six feet, and I landed sprawling beside an enormous, unexploded shell.

I prayed that it wouldn’t be detonated by the heat of the fires that I could see everywhere as I hastily got to my feet. As I ran as fast as I could from the devastation I saw why the doors could not be opened – the bolts had been secured with barbed wire by the German guards.

The air, the sky, all around me was thick with reeking smoke. Ammunition from a train that had been on the line alongside the prisoners was exploding furiously,whilst from above, a continual torrent of debris rained down mercilessly.

I dodged between two trucks, and crouching, twisting, ran like a hare across the wreckage of uprooted lines and broken wagons, away from the ghastly scene.

With mud up to my calves, I struggled through a ploughed field as other men in groups or alone also staggered on their way to life and freedom.

Some fell and rose again lathered in mud and sweat, but others not so lucky stayed down, destroyed by the lethal wreckage that was being thrown in all directions by the force of the exploding munitions.

A few yards in front of me I saw a man felled by a falling wheel, and retching with horror and the effort of running, I clearly saw that there was nothing anyone could do to

[Digital page 35]

save him.

I came to a river, my tortured lungs forcing me to slow down, and paused by a group helping an injured South African.

As they said they could manage, I moved on, looking for a likely place to cross the river.

I met several German guards who had survived the bombing, but they were unarmed, bemused, and just as frightened as I was, so presented no threat to me.

Close to an unguarded bridge I came across a soldier, alone and sprawled on the ground, his head covered in blood but nevertheless still conscious.

I half-dragged, half-carried him to the water’s edge and in the shelter of the bridge washed the blood away as best I could.

Fortunately, his injury had looked worse than it was and he was soon reasonably fit once more.

He decided to stay under the bridge for a while longer, but urged me to go. Fortune dictated that we would meet again some years later when we both re-joined the Territorial Army.

Over the bridge and some distance further on I almost ran into the arms of a German soldier coming the other way.

He shouted to me to go back into the town and surrender, but as he also was unarmed I told him to get stuffed, and carried on.

I passed through a cluster of farm buildings and met Italian women hurrying to the scene of the carnage.

Some were in tears, crossing themselves and crying, “Madre mia, povere tutti.”

One stopped me to tell of a wounded man close by and I found him, terribly burned, slumped on a chair in front of a house. Women were doing the best they could for him, and several soldiers were also trying to help.

As neither group could understand the other, I stayed to translate, discovering that the men were New Zealanders and that the women had sent one of their neighbours into town to fetch a doctor.

For everyone’s sake I hoped that expert medical assistance would soon arrive.

[Digital page 36]

About half an hour later, as I was feeling far enough away from the marshalling yard to be able to relax, I came upon another escapee talking to an Italian woman.

She seemed very friendly and asked us both into her house for a meal.

We agreed readily, but in the circumstances were uneasy during our stay.

How right we were.

Before very long, someone in the house spotted a company of armed soldiers starting a house to house search, so wishing our kind host farewell and gratefully accepting a loaf of bread, we hurried away into the nearby hills.

With my new companion, progress over the rough ground was reasonably good and we were soon into the trees covering the lower foothills.

We could now pause in some safety to plan which direction to take.

Switzerland at about five hundred miles distant was out of the question, and back to the Sangro where the line was by now consolidated with minefields and heavy defences, was only marginally better.

We struck out south, hoping for the best.

From the high ground that we now occupied we could see the vast pall of smoke hanging over L’Aquila, could hear the explosions that were still racking the area, and hear the occasional rattle of small arms fire as prisoners were being rounded up.

The afternoon was well advanced when we met a party of South Africans travelling in the same direction and my companion, who came from Durban wanted to stay with them. I thought that it would be safer not to go with such a large group so I decided to let them go and I would rest up for a while.

For a long time I heard them crashing ahead, and I knew then that my decision had been the right one.

Eventually, after what seemed to be an age, I got to my feet and trudged on feeling lonely and wondering where I would spend the night.

Trying to sleep in the open at that time of the year is not very pleasant to say the least and although I was tired after

[Digital page 37]

the eventful day, I was prepared to walk on throughout the night unless I happened upon some suitable shelter.

Dusk was closing in when I first heard the sound of something behind me.

I had not seen anyone, even in the distance, since leaving the South Africans so I stopped to listen carefully.

I heard the sound of loose rock being dislodged and now knew for certain that someone or something was trailing me. I picked up a handy stone, determined to defend myself, and crouched behind a rocky outcrop. Waiting guardedly, I heard a low whistle, but I kept quiet, straining to see who might be there in the gloom.

Came the whistle again, and then a very English voice crying, “Hello, I’m a friend.”

I emerged from my cover, hoping for the best but prepared for the worst. To my immense relief no enemy with threatening gun faced me in the night, just an ordinary-looking fellow in British battledress looking as apprehensive as me.

Albert came from Nottingham, and never were two Brits more pleased to meet one another.

He was also a survivor from the bombed train but had been re-captured in the hills with several other men.

Managing to escape again he had disappeared into rocks and scrub,and apart from a couple of shots that had happily missed their mark the Germans had not pursued him.

The path that we had followed throughout the night seemed to generally lead south and we reckoned that we were about thirty miles from Avezzano.

Just before dawn we stumbled upon one of the roughly constructed huts that are dotted among the hills and mountains of the Abruzzi.

Pushing open the door, we found the place empty, and in one corner, a pile of dried, sweet-smelling corn leaves.

We were asleep in no time.

Our destiny was to stay together for the next few months, defying the harsh Italian winter and the ever-present menace of the occupying German troops.

[Digital page 38]

AFTER THE SECOND ESCAPE

[Digital page 39]

After my escape from Sulmona in September 1943, for one reason or another I had been separated from my original companions.

With the bombing of the prison train the last link was broken and I was unaware of what had happened to the men who had crossed the Sangro with me on that fateful day in November.

Considering the traumatic events of the weeks leading up to Christmas that year I was exceedingly lucky to be still alive and in one piece, and my new travelling-mate Albert felt much the same way.

Although we were walking generally towards the south we knew that the frontline would probably be solid by now, and that with the onset of winter, nothing much would happen until the Spring.

Any day now, the snow would arrive, and if only we could keep out of the clutches of Germans and fascists we might still stumble eventually into the Allied Forces.

We first saw Acciano from the wooded hills through which we had been walking for two days.

As it was only early afternoon we had no intention of stopping and anticipated that we would cover several more miles before looking for a night shelter.

The track that we were taking led down to some cultivated fields and we suddenly came upon a group of three men who at first sight appeared to be Italian contadinos.

Too late to avoid them, we pressed on with a muttered “Buon giorno” as we passed by.

Imagine our surprise to hear a broad Scots voice reply,

“How far do you think you’ll get in those uniforms?” Apparently, although soiled and tattered, our battle dress was still unmistakably British.

It transpired that our new acquaintances were also ex POWs who planned to stay in the area for the time being. They had been down as far as Avezzano but had found the area from there to Sora and Cassino stiff with Germans. Wisely, they had fallen back.

Bruno, the Scot from Glasgow was certain that if we went any

[Digital page 40]

further south dressed as we were we would be courting disaster.

He suggested that we should stay with him and his friends in a large cave which he said was nearby.

This seemed sensible, and our decision was confirmed when we eventually saw the place which was warm and reasonably comfortable.

A wood fire smouldered in one corner and leaves and dry bracken covered the ground.

Bruno told us that the cave belonged to the mayor of the village we’d seen from the hills, Acciano, and if he approved of our stay we would be fairly safe for the time being. Furthermore, Guerrino would see to it that the villagers brought us food.

It was some time later that an elderly, dapper little man arrived at the cave and was introduced as the village podesta. He was suspicious of us at first, but we finally convinced him that we were not German spies, which was just as well for he suddenly produced an old-fashioned pistol from his pocket and told us what our fate would have been.

Having agreed to help us, Guerrino said that it would be safer if Albert and me took over another cave some half-mile distant, as five of us together might not be very wise, and Germans did sometimes roam the area.

The alternative cave that he took us to was well-hidden among trees which would help to disguise smoke from a fire.

We could have fared a lot worse.

We stayed there for a number of days, only going out to forage for wood to keep the fire going, for the nights were now quite cold.

The entrance to our hideout was about two feet by two, just room enough to crawl into, and at night we pulled in a bundle of tree branches to fill the opening.

Only an expert woodsman would have known that we were there. True to his word, Guerrino sent somebody up from the village with food for us most days.

Domenica, was one of the young girls who came regularly, and we got to know her very well.

Sometimes the mayor came himself, and often would stay to talk and tell us about his communist connections and how his party would come to power once the enemy had been defeated.

[Digital page 41]

The days passed quickly, much of the time being spent in making certain that the fire didn’t die, for matches were scarce and we only had half-a-dozen left in our box.

With the help of villagers who came to see us, to bring food or just to talk, our Italian improved rapidly.

Occasionally, we saw German transport moving along the road below, and once we heard machine-gun fire in the hills beyond Acciano.

We were told that enemy patrols had re-captured a number of ex-prisoners, and that two British officers living in a cave about five miles away had been killed when Germans had surprised them at night and had thrown in hand-grenades.

The Krauts were always handy with this particular weapon and this piece of news made us both jittery, but nevertheless we decided to stay put.

Bruno and his friends had already moved further on. The first we knew about snow falling was hearing distant voices and the sound of shovelling.

We tried to push out the brushwood door, but it wouldn’t budge, and then we saw the ice and frozen snow.

Fortunately, Guerrino had thought of us during the night, and it was he and his mates who were now trying to dig us out.

When they finally hauled us into the open, they fell about laughing, thinking it was a great joke.

We couldn’t remain in the cave, and in any case, the villagers could no longer struggle up the hillside to bring us food.

The Mayor said we would have to come into the village and that he would move us around from one hideout to another every few days.

Various barns, a wine store, and other discreet accommodation became our temporary homes, and then suddenly it was Christmas morning.

It wouldn’t have meant much to us, but towards midday we had a visit from one of the villagers who wanted to take us in for a meal.

The new snow was piled high in the narrow streets and not many folk were outdoors.

Those we passed took little notice of us beyond exchanging a traditional season’s greeting.

The kitchen that we were brought to was a welcome sight with

[Digital page 42]

its open wood fire blazing merrily, and we were overcome with gratitude. The cooking pots set to one side of the stone hearth, their contents bubbling lazily, sent forth an aroma of olive oil, tomato, and herbs – suddenly, Christmas looked good again. Smiling a welcome, an older woman motioned us to sit at the well-scrubbed table, and another member of the family brought glasses and wine.

I had heard of polenta before, but had never experienced it as served by country-folk.

A large pot was lifted from the fire and its contents emptied over the bare wooden table-top.

Fascinated, we watched the glutinous mass spread slowly until we were certain that it would go over the edge, but before disaster struck it all stabilised and came to a halt. The women then emptied the other pots over this edible ‘tablecloth’ and topped it all off with a generous dusting of grated cheese.

Others joined us and we sat around the table carving out chunks of the meal with forks and washing the mouthfuls down with our host’s excellent wine.

After the polenta we were tackling a mound of tiny, round pancakes when we heard a banging on the door.

Looking out of a window, one of the other guests reported that there were two German soldiers at the door, and we got to our feet hurriedly and prepared to move.

A young girl beckoned us to be quiet and to follow her to a room with a ladder that led to another floor.

There, a window opened onto a series of roofs over which we could escape if necessary.

The girl whispered, ”Stay, I’ll tell you if they come inside.”

Apparently, the soldiers were only after wine, and once they were given a bottle they went away.

This little adventure made us realise however what danger we were putting the family in, and we said that we would leave immediately.

The Italians wouldn’t hear of it however, insisting that it was Natale and that we must finish the pancakes and wine. Albert had been batman to a staff Brigadier and one of his skills was hairdressing.

Somehow, he had managed to keep the tools of his trade with

[Digital page 43]

him throughout, and now he promised to trim my flowing locks and heavy beard to celebrate Capodanno – 1944. Guerrino remarked on this when next he saw us, bemoaning the fact that the village no longer had a barber.

A number of Germans had moved into the top part of the village since our arrival, but they seldom strayed into the lower part where we were.

We now had old, faded and patched topcoats covering our uniform, but even so, on the Mayor’s insistence we didn’t move around more than necessary.

A few of his closest friends, however, managed to take advantage of Albert’s skill with scissors and clippers. Early on in the New Year, Bruno and his pals returned and lived with us for a time in the village.

Unfortunately, they were all aggressive types who became a menace if they were given any wine, and that was the last thing we wanted with Germans on the prowl.

We were glad when they finally left the area, and so was Guerrino.

Some days were more scary than others.

One morning the village streets were filled with Germans quite suddenly, and we were whisked away to a prearranged hiding place on a roof with a number of Italian men.

I asked what was happening and was told that an avalanche had blocked the road to the upper village.

The Germans were rounding up every able-bodied man, woman and child to clear away the snow and other debris.

Eventually, with the clearing done, the villagers returned and normal life resumed.

Other problem days were when the German mobile canning units moved in to confiscate and slaughter anything that could be eaten.

The system was simple.

Surround the place with troops, flush out any pigs, chickens, or whatever – kill, cook and can.

The Germans were very good at this ploy, but so were the Italians in hiding or spiriting away their stock.

A pig dressed in baby-clothes was not unknown and almost every cave in the hills contained a precious animal, money or other treasured possession. We managed to keep reasonably clean during these trying

[Digital page 44]

times, washing in cold water and using a rough soap made out of earth oxide and animal fats which smelled awful.

We tried to clean our teeth with chewed twigs, but this wasn’t very successful and it was most probably the iron-hard, country bread which was our staple diet that kept decay at bay. Occasionally, one of the women would take our shirts and wash them, and this service following local practice, always included picking over the garments to remove the inevitable lice.

Pidocchio is one of the Italian words that I will never forget. Socks and undergarments were by now a luxury of the past – like the Italians, we wrapped our feet in strips of any rags that became available.

One day we were talking to one of the villagers and Albert said how much he would enjoy a nice, hot bath.

To his surprise, the woman indicated that it could be arranged. The following day she arrived at the stable where we were then housed carrying a large, wooden tub – the sort used for treading grapes, which she set down on the packed-mud floor. Others arrived with jugs of hot and cold water, and with much laughter, a party atmosphere soon reigned.

Poor Albert had to be persuaded to undress, but with so many willing hands present to assist him he was soon as naked as the day he was born. Three or four of the women hustled him into the tub and quickly began washing him all over whilst the audience shrieked with amusement.

The word must have spread, for more and more people crowded into the barn and added to the ribald comments that flew around.

By now, Albert was past caring, and lay back in the warm, relaxing water like some modern-day Caesar submitting to the attentions of his handmaidens.

If I had thought that for one moment I would escape the same treatment, I was wrong.

Fiery, Latin blood had been aroused and I was already a marked man.

Like Albert, I lay back and thought of England!

Where it all might have ended I can’t imagine, but Guerrino arrived on the scene and sent the whole lot packing.

With the German winter line firmly fixed around the river Sangro, the enemy had been able to deploy at least one regiment to seek and destroy or re-capture the many ex-prisoners still at large.

[Digital page 45]

It has since been estimated that more than five thousand men were loose at that time and they must have been a bit of a problem for the enemy.

Some German troops operated in civilian clothes and were often aided by fascist supporters. Summary executions were commonplace, and no doubt old scores were settled.

Most of this was known to the well-informed Guerrino who somehow managed to keep his tight little community immune from spies and traitors. With the new year however, the general situation became more fluid and it was dangerous for us to remain in the stable any longer.

Accordingly, late one evening Guerrino arrived to take us to a small, two-room house that was empty and in another part of the village.

We could spend the next few days there, but then we had to move on. There were reports of heavy fighting around Cassino and he thought that if we could get to Trasacco safely there was a reasonable chance that we would be overrun by an Allied advance in a matter of weeks.

Our new quarters were luxurious compared with the stable, but we felt uneasy there and soon resolved to leave.

A tapping on the locked door the next day startled us until the caller said who it was – Domenica, one of the local girls who often brought us food.

We let her in, and as there was nowhere to sit, the three of us sat on the old-fashioned bed with its mattress of dried corn leaves.

We laughed and talked for a long time, and if any of us thought of other activity, we quickly put it aside.

As it was, we were in enough danger without risking the wrath of the villagers over the young girl’s virginity, and in due course she left, intacto.

The Mayor came for us early the next day, and the three of us walked out of Acciano without meeting another soul.

Soon we were up into the wooded hillside and there Guerrino left us after indicating which way we should go.

We stayed not too distant from the village for several days, not convinced that we should head for Trasacco, and having found an

[Digital page 46]