Summary

After having to force land his plane, Peter Coxell was taken in by the Italian locals, in particular Dr. Thomaso Giretti and his family, who became life-long friends. After being provided with clothing and footwear (having to sacrifice his pair of Alpini Rgt boots for an inferior pair of shoes) Peter joined up with Ralph, a South African airman who had escaped from a POW camp near Padua. For seven months, the two evaded capture with the willing assistance and goodwill of the locals until, on 15th June, they made their way behind the Allied lines. After repatriation and a short leave back in the U.K., Peter opted to continue flying a Spitfire and was involved in the fray in Belgium.

he full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

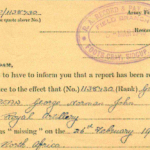

[Digital page 1]

Coxell, Peter

Never a POW but plane crashed behind German lines in the Marche and very much ‘on the run’.

[Digital page 2]

[Handwritten note: Never a PoW but planed crashed behind German lines in the Marché and very much on the run]

[Title] Circumstances leading up to my being an evader in Italy from November 1943 to June 1944.

It began with my volunteering for aircrew duties with the RAF in June 1941 when I was 18 years old. I attended aircrew selection interviews over a period of two days and was accepted for pilot training. At this stage I was sworn in and given my service number but due to the bottleneck in training I was sent home on deferred service with a little lapel badge to show I was a member of the armed services. I was subsequently called up in September and received basic training at the Aircrew Reception Centre, London followed by Initial Training Wing, St.Andrews (ITW).

From home leave I was posted to South Africa (RSA) for pilot training. It took five weeks aboard the P & O liner Otranto to travel from Liverpool to Durban then by train to the Transvaal. After elementary training on Tiger Moths and service training of Miles Master II’s, I obtained my wings in January 1943. I was posted to Egypt for operational training on Tomahawks and Kittyhawks then posted to 250 (Sudan) Squadron then resting at Zuara, Tripoli following the end of the North African campaign.

I started operational flying in Sicily and on to Italy via Taranto – Bari – Barletta – Foggia and finally Mileni which was part of the Foggia group.

On the evening of November 2nd, I was in our mess tent where the ops board was displayed for the following day and although not detailed initially the C.O., Major Theron (SAAF), approached and told me he had put me on in place of a Sgt. Cross (RNZAF) who I understood had been drinking too much. At 0600 hrs 3rd November four of us were sitting in our cockpits waiting for first light to take off on an armed recce with long range tanks. We were supplied with a mug of tea by the most helpful mess corporal. We flew up the coast slightly above Ancona and turned inland to look for targets, passing over Jesi aerodrome we saw two Italian aircraft and the leader decided to straff them there being nothing else on offer. After attacking and pulling up, I saw my red light on the dash flashing to indicated engine overheating and at the same time saw glycol pouring out of my exhaust stubs. A quick look at my altimeter showed 1500 ft above sea level but not knowing exactly the height of the terrain I immediately decided to force land rather than bale out. Unwittingly a lucky choice for had I jumped I would most certainly have been tracked by the enemy and captured. As it was I travelled some distance inland away from the coastal area occupied by the Germans.

Choosing a field I opened the cockpit hood locking it back and tightened my safety harness; this was of course a wheels up landing and completely forgetting the long range tank I slid to rather an abrupt stop in a reasonably level field with some low grape vines. Getting out I was at once approached by some locals who seemed surprised that I was on my own. In the event the danger of landing on the long range tank was eliminated as it was brushed off at first contact and left many yards behind; the locals thought it was a bomb until we managed to find the word benzina (petrol) and all was well. I was then quickly ushered into the nearest quite isolated farmhouse and put in the loft where I was to stay for best part of 36 hours during which time I was kitted out with civilian clothes and had visits from several locals among whom was Thomaso Giretti. Thus started a wonderful relationship with that family.

A brief note about escape kits. We had very little instruction on escape and evasion during our training but it was always a time honoured thing to take the clock if you crash landed which I had

[Handwritten note in right margin: Landed near Jesi. Other places: Cerividone, Osimo, Porto Recanati, Civitanouva, Monte Bianco, Rotella, Appiano, Fararone, v. near Chieti]

[Digital page 3]

remembered to do. The idea was to keep it and have it mounted as a souvenir; however this was foiled by it being dropped and broken when I was showing it to someone and it had to be discarded. I did have my little plastic box containing basic first aid kit with morphine ampules which I gave to Doctor Giretti; I also had my maps covering the area which proved to be invaluable. Although the date was November 3rd, the weather was still very agreeable and my flying clothing consisted of merely a one piece flame retardant flying overall over a pair of boxer shorts. My footwear was another story; I was wearing a pair of Italian Army (Alpini Rgt) boots; they were superb two tone leather and would have been the pride of any fell walker today. They were originally studded with hobnails but our Engineering Officer insisted on the removal of same to prevent damage to his cherished aircraft. The rub came when my Italian friends expressed horror at the thought of me walking about in such distinctive footwear fearing it would be a complete give away. They were thus exchanged for a pair of distinctly second hand shoes. My parachute incidentally had been quickly taken into custody and later used by the ladies for essential clothing. I understood that petrol had also been siphoned from the aircraft and the long range tank.

After many visitors and much discussion in my loft it was time to move on and during the hours of darkness on the second day Doctor Giretti arrived in his little Fiat 500 and I was folded into the rear seat with my head down and driven to the Giretti’s house at Cerividone five or six miles away. Here I was introduced to Ralph and John, two South Africans who had escaped from their POW camp near Padua at the time of the Italian armistice and in the following two months had made their way south and were being sheltered by the Giretti’s. I never knew John’s surname because our relationship was very short as he absconded into the night a couple of days later. The obvious reason for this was that he was quite short and dark haired whereas Ralph and I were both six feet and fair haired. John obviously thought he stood a better chance on his own; we never heard of him again.

Having current maps and knowing where the front line was and the fact that at that time the advance was still quite rapid, it was decided that Ralph and I would immediately start walking south in the hope of getting through the lines. I greatly benefited from Ralph’s company because he was experienced in the ways of living rough and also had a smattering of the language picked up in POW camp. He was incidentally a bombardier in the South African Artillery and had been taken prisoner at Tobruk.

I estimated we had to travel south about 150 miles in a direct line but our route would be far from direct and mostly up and down the endless valleys of the Appenine foothills. We reached the Osimo area in the first day and on to PORTO RECANATI area; by the 17th November we were near CIVITANOUVA. It was here that we heard of a British officer operating in the area trying to contact escaped POW’s and organise rescue. Subsequently on the 20th we met this man who introduced himself as Capt Simpson; he was wearing army battledress without headgear or badges of rank etc. and told us the idea was to evacuate from the beach with landing craft at night and we were given a map reference and told to meet on the 22nd. In retrospect I wondered if he gave his correct name for reasons of security. The outcome was that having negotiated the busy coastal road and railway used by the enemy we duly made our rendezvous on the beach and although it was pitch dark, I estimated that there were some 20 or 30 people gathered there in groups; many were smoking in spite of being told not to do so. After some hours and assuming signals having been made seaward, we were told it was no go and instructed to repeat the exercise on the 24th. We filtered back into the safer countryside and came back on the 24th and the 28th to a repeat performance. After the last attempt we had lost touch and by the 1st December we were again heading south and by the 9th December we were in the

[Handwritten note in right margin: Was in contact with Giretti family for 25 years+]

[Digital page 4]

MONTE BIANCO area and 12th December we were in the ROTELLA area and I recorded that I was feeling rough; this was the only time I ever mentioned or recalled feeling under the weather. This is quite remarkable bearing in mind that during the whole period I never had access to a change of clothing and had no outer garment for weather protection during a particularly severe winter by Italian standards.

On the subject of health, our washing facilities were very basic; seldom any hot water to be had and certainly no soap available. I had no shaving kit and we followed the example of the Italian men of only shaving once a week on Sundays; this entailed borrowing a cut throat razor wherever we happened to land up on the Sabbath; the first few efforts of laying the blade on one’s face were quite alarming but need’s must and it was done. I did leave my upper lip and thus grew my first moustache. Our drinking habits in the pilots’ mess at this stage had been dictated by the fact there was no beer available at all and for some reason we had adequate supplies of gin, so every evening it was gin with occasional supplies of local wine. These seven months of abstinence were probably quite a good thing for my general well being and the forced exercise of daily walking no doubt improved my fitness level. Anyway other than the one mention of feeling groggy, I was very fit indeed. The lack of a change of clothing did lead to the fact that in no time we were invested with lice, not helped by the fact we were usually sleeping with the cattle. Being a non-smoker I always accepted offers of cigarettes and put them behind my ear for supposed future use when in reality they were given to Ralph to smoke. I did have some benefit however because quite often at night we would strip down and with the use of a cigarette end run along the seams of our underwear to delouse ourselves but we were never completely free.

Being ‘on the road’ very much like the old tramp in pre-war England followed a regular routine. During the day we would keep clear of any villages and either approach a solitary worker in the fields or call on an isolated farmhouse and ask for a drink of water, openly explaining that we were English escaped POW’s. The result was invariably great sympathy and being provided with something basic to eat plus a glass of vino; often we would be given a hunk of homebaked bread drizzled with olive oil and a touch of salt. The evening routine would be to select a very secluded farmhouse and wait until dusk before approaching so the occupants could feel our visit had not been observed and the reception would be the same. Pasta in its many forms was the basic diet with polenta and bean soup regularly served up; this with the nice crusty bread that every house made two or three time a week. Very little meat was seen; a few slices of homemade salami were regarded as a treat.

Some meals during this period did make an impression. The system of farming at the time was that the Padrone (Landowner) probably lived in the town or village and had tenant farmers in his isolated farmhouses in the area; these were the Contodini who had to keep account of any livestock to his employer and any butchering of cattle, pigs etc. was very closely monitored. I remember the occasion when a pig was to be slaughtered at the Giretti farm where I was staying during Ralph’s illness; all and sundry gathered for the event with much celebration and glasses of vino. It proved the point to me that the only part of a pig that is no edible is it’s squeak. The blood was bled off into shallow trays and later when completely congealed was cut up and fried and we enjoyed this with the wholesome bread. On another occasion at the same house, I thought we were having a special treat of rabbit but afterwards when we remarked that we never saw any wild rabbits in Italy our host informed us we had in fact eaten cat and to prove it he asked his good wife to show us the scratches on her arm as she had been the executioner.

[Digital page 5]

The classic Italian dish of polenta was another eyeopener. It was cooked in a huge cast iron cauldron over the open fire to the consistency of thick porridge and had any scraps of meat tossed into it; table was scrubbed clean and when all were sitting round the polenta would be poured onto the table and it would spread out like lava from a volcano. Everyone being duly armed with a fork would then carve into it until our forks met in the centre of the table.

The country was occupied by women, children and elderly males. Any men of military age were either forced labour in Germany, POW’s in the UK or Canada or had escaped to the hills and joined the partisans. We were frequently regaled with stories of the missing menfolk who were POW’s safe in the UK and obviously being treated well. This created a good impression on our hosts and no doubt had great bearing on the way we ourselves were received and looked after; this was the normal reaction. When on the move we would seldom stay in the same farm for more than one night in fairness to our hosts; if we did stay longer, it was normal to take to the countryside in the morning and roam locally, returning in the evening. It became obvious that if we stayed in one area for a few days it was soon common knowledge to the neighbours because they would want to come and visit us. It was in this way that were learned of other escapees being in the area and on the odd occasion we were able to meet up and exchange news. None of these isolated farms had electricity and none had radios so for weeks on end we had no news of the outside world, only rumour upon rumour of the progress of the war.

December 15th, I record was spent in the APPINIANO area and on the 17th we met an unnamed L/Col and a Captain who were organising yet another scheme which for some unknown reason came to nothing and we continued south to the FARARONE area. By the 26th (what ever happened to Christmas?), Ralph was becoming quite poorly with an obvious attack of Jaundice. This was not helped by the fact that on the 31st we had heavy snow and the going was hard and we decided to head back north hoping to get back to the Giretti’s and help from the doctor. However before we put this plan into operation we were invited to join a group of Italians who with the help of a local guide were proposing to walk through to the Allied lines.

This attempt started on January 8th and I record there were thirteen of us and we would be walking during the hours of darkness with prearranged resting places for the daylight hours. We walked solidly for four days and on January 12th we were near ROSCIANO (near CHIETI) when the plan was abandoned. The only incident of note during the walk was when walking in crocodile fashion and blindly following the person ahead we descended an embankment to cross a road when the people ahead were all calling out ‘buona notte’. On crossing the road, I saw in the gloom a solitary German soldier in his almost ankle-length greatcoat and a rifle slung over his shoulder; we just echoed the greeting and disappeared into the field across the road. I would think the poor fellow was too surprised and probably frightened to do anything. I don’t suppose he ever told anyone of this encounter. The plan was then called off.

So the return trek began and I record that on the 24th January we were near COSSIGNIANO where we renewed acquaintance with an elderly farmer and rested up for a few days for Ralph’s benefit and after rather slow progress in bad weather we finally reached CERIVIDONE on March 2nd. Ralph was immediately put to bed and attended by Dr. Giretti. I was moved out to one of the isolated farms; this was run by a delightful couple, Guido and his wife (where we had eaten the cat). This turned out to be my longest stay in any one place; it was a few miles from the Giretti’s house and I had regular

[Digital page 6]

visits from the family and in turn I was often taken up to the house for a meal and a chat. It was during this time that Thomaso told me he was in touch with the local partisans. I was never told exactly where they were based but I now believe it was the nearby town of CINGOLI which was 700 metres above sea level and off the beaten track as far as the Germans were concerned and the roads leading up to it could be easily monitored for approaching traffic.

The outcome of this contact by Thomaso was that I was required to supply my service details for them to be verified and communicated to the UK by radio, presumably to MI.9. I was subsequently told that the partisans were organising an escape scheme and they had been instructed to give priority to aircrew members and I should stand by for this event. On March 25th after dark I was taken on foot with Thomaso, not being told where I was going but it was a considerable walk and mostly uphill to the edge of a town (Cingoli?). Here I met the partisans and was introduced to other evaders and told they were all aircrew; the only ones I remember were an Australian Spitfire pilot and an observer named Ben who was from Norwich.

Ben had been a member of the crew of a Halifax dropping supplies to the partisans and had been forced to bale out and subsequently been taken care of by them. The Australian had been operating from Malta and whilst attacking an Italian floatplane had been shot down by the rear gunner and he was quite mortified by his misfortune relating how the Italian crew had visited him after his capture.

Early the following morning we were introduced to our driver who was a giant of a man with red hair and turned out to be an Englishman who had escaped from a POW camp and had joined up with the partisans. No details were given of the proposed escape scheme but a low sided lorry about the size of a small three tonner was produced; it had a tarpaulin cover and we were instructed to climb aboard under the cover and two partisans got in the rear with us both being armed with sten guns. These two positioned themselves at the rear which was left uncovered. Absolutely no instructions were given as to the plan we were about to embark on and we assumed it was to be yet another boat scheme and with the fact we had been assured of the partisans’ radio contact with London, we trusted them completely in spite of the fact this was all happening in daylight. I suppose we assumed there would be a safe house for us to lay up in prior to a night pick up.

I suppose we had been on the road for half an hour, lying in the semi-darkness when we were alerted to some shouting from the cab which contained the driver and a further two partisans; the lorry was slowing down almost to a stop, then with suddenly changing gear started to accelerate accompanied by more shouting from outside and then the firing of a heavy machine gun as we gathered speed. My abiding memory is of the very slow rate of fire of the machine gun compared with the light rattle of a sten gun, not that our guards returned fire. I remember thinking that perhaps the woodwork sides of the lorry would start splintering at any time but it stopped and we sped on into the countryside. After about twenty minutes we stopped and all got out and the driver told us to scatter as he was going to destroy the lorry. Somewhat relieved to be out of that situation, we duly dispersed in all directions and I found myself alone after a while which was by far the safest way to travel under the circumstances and I found my way back to CERIVIDONE none the worse for wear.

Having subsequently read of the activities of the partisans I am now quite convinced that this was the most dangerous incident of my whole time as an evader. It was generally accepted that the Fascists were a greater danger to us than the Germans as they had been known to shoot evaders without

[Digital page 7]

handing them over to the Germans and they gave the same treatment to their fellow countrymen who were partisans. I had reasonable optimism that should I fall into German hands I would merely be treated as an escapee in spite of the fact I was in civilian clothing. However I am convinced that had we been taken prisoner at the Fascist road block we encountered, no questions would have been asked and we would have been executed on the spot. I was told later that it was a Fascist road block and this accounted for the memorable slow firing machine gun and not a modern German weapon.

I was back at the small farm with Guido and all was peaceful for a while but on April 4th the balloon went up and were told to flee as Thomaso and another man had been arrested by the Fascists. We immediately started south once more keeping gently on the move through April into May picking up on some reliable contacts; the weather was much improved making life much easier. We were also encouraged by the endless rumour of the advances now being made by the Allies to the south. I recorded that early in June we had rumours of Rome, Pescara and Chieti all being taken. But strangely we had no indication of the European D Day invasion.

At this time we were hearing gunfire to the south which was encouraging, and we were told that the Germans were pulling back with a lot of looting of livestock etc. As a safety measure and helped by the weather we were spending nights out in the open, there being plenty of cover in the cornfields. The actual crossing the front was quite an anticlimax; the noise seemed to get closer one day and then there was a complete lull for perhaps a day when we suddenly realised the battle noises were now behind us to the north. It was then decided to travel east towards the coastal area where the advance would obviously be taking place. On or about the 15th June we sighted a Sherman tank and were able to make contact with the Allies in the form of the Polish Brigade. I am very vague about the following few days but we were passed back to a British unit and here I think Ralph and I separated and I was taken to a repatriation camp on the outskirts of Naples.

At Naples it was the luxury of hot showers, delousing and getting clean clothing and new shoes. I think the medical check up was quite cursory as I was obviously very fit. Red Cross cards were provided which I promptly despatched home. I learned later that by coincidence my parents received the card the same day it was announced that Ancona had been taken. My commanding officer had written to my parents saying I had landed safely in that area and my father had marked it on his war map saying they would try not to worry too much until the Allies reached Ancona. I think I had about a week or ten days of enjoyable leisure at Naples. I remember a trip to the Naples Opera house and also accompanying the mess officer to buy wine. The poverty in Naples was very apparent.

Eventually I was allocated a place on an American DC.3 and flown to Algiers where I overnighted and the following morning continued to Casablanca and thence by USAF Liberator to St. Mawgan in the UK. I was sent home on leave in the rather unlikely dress of a F/Sgt of the RAF in khaki battledress. After leave, I was summoned to the Air Ministry and de-briefed by a friendly Wing Commander who virtually offered me a choice of postings and I rather rashly opted to continue operational flying on a Spitfire squadron. I received a posting to 75 OUT Eshott and joined a course halfway through to qualify for joining 127 Squadron, 2nd TAF and on to the fray in Belgium.

Thomaso Giretti was subsequently released by the Fascists and later received General Alexander’s written commendation for the assistance given to many escapees during 1943-44.