Summary of Bob Rogers

The text comprises Rogers’ whole life story, foucssing particularly on his war-time experiences. He recounts important events leading up to his capture in North Africa and his relationship with his colleagues. Once captured as a prisoner of war, he had been taken aboard Nino Bixio which was to be torpedoed by British Forces – a pivotal moment for Rogers.

Still a POW, they were held in a huge shelter, later taken to work on a farm, from which Rogers and fellow captives would escape. They were aided by locals throughout Italy, spending a lengthy period in the small village of Gaina in the mountains of Italy before crossing into Switzerland. Rogers’ return to England is slow, and eventually he is discharged to carry on his personal journey after the war ends, including visits back to Italy.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital page 1]

SIXTY BONUS YEARS: a tale of survival

by Bob Rogers

[Image of Bob in the countryside covers the background.]

[Digital page 2]

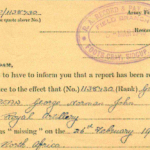

Foreword

It is my privilege to honour my Dad by writing this foreword.

My brother Michael and I grew up with these amazing stories of Dad’s war years. I always marvelled that someone who had been through these times could then go on to lead a normal life!

I remember Dad’s wisdom when he said that he regarded every day since the Nino Bixio as a bonus. With this positive attitude it is no wonder that Dad is a survivor and is a fit man in his eighties with a great outlook on life.

Our lives have been blessed by amazing connections. The first one brought great sadness to my mother. It was because my mum lost her first husband (Roger Peel) that the connection between Mum and Dad began.

Of course without that connection none of our family would have been brought into being.

The connection with my husband Bill’s family back in 1958 has brought the blessing of my marriage and our own precious family.

Dad’s time in Gaina has given us an incredible link with the Manessi and Ravarini families. This strong bond will continue to develop and is now touching four generations.

We thank Dad from the bottom of our hearts for taking the time to write this true story down, giving the family wonderful connections and bonds to treasure throughout our lives.

With thanks from your loving daughter Lynn, on behalf of all the family.

December 2002

[Digital page 2, original page 1]

[Handwritten text above the photograph] all the very best, good health to Stephen

From Bob Rogers. 10.6.03

[Photograph with caption] Private Samuel Robert Rogers

[Page Footer] Mr Rogers – Memoirs [Page] 1

[Digital page 3, original page 2]

At Home With My Ma

This is a tale that I would like to dedicate to my Ma, on behalf of all of her twelve children and the others she took into our family, her parents and two nephews who were orphaned. All taken care of by a most remarkable woman who was a tower of strength to us all. Myself, I came seventh in the scheme of things, and even though things were pretty tough in the 1920s our house was a warm and, of course, hectic place. But filled with love and good humour along with the most aromatic of smells – fresh baked bread. My Mother must have had a constitution of a horse, the amount of sheer hard work she did daily was just exceptional. She baked at least three times a week; I can smell the fragrant smell of it now. Washdays were a monumental task – scrubbing, boiling, and wringing – all done by hand in those days. The kids were recruited early in life to help turn the handle of the old wooden roller mangle, and taught to use the poss stick, a heavy peg like thing used to pummel the dirt out of the clothes in large wooden tubs. Her only rest or break was every two years; she was confined to bed to have a further addition to her brood. But always a smile and a helping hand to all around the village.

[Photograph with caption] Bob’s parents with the first of their eleven children.

[Text continues]

Amongst my earliest recollections is one when I was four years old and had been persuaded by older kids to get some matches from home. lt was around Guy Fawkes Day and the kids had a huge bonfire prepared for November 5th. They had a large hole inside it and on the cold nights they would gather in it with a

[Digital page 3, original page 3]

candle in a jam jar for light. So to light this candle, I was to get the matches and, by standing on the brass fireside fender I could just reach up to the mantelpiece where they were. Unfortunately Dad came to get the box of matches soon after and of course they were gone. When we came into the house later he said to us all.

“Who took the matches”?

“Not me”!

everyone cried – me louder than anyone! “Right,” he said “A walloping for all of you”. Tightlipped, I took the smacks with the rest of them. He was usually a gentle man but he said that liars had to be punished and although I never did own up, the lesson stuck with me for life.

My early recollections were also of seasons of outdoor games. We all played marbles, rounders or swapped cigarette cards, according to the seasons. Guy Fawkes Night was a very big thing that took long preparation of gathering and building a huge bonfire of rubbish, which was guarded diligently against rival gangs. Even in our small village we had separate zones, each with its own clan and bonfire, and raiding of rubbish was a full pitched battle for weeks before November the 5th. But a glorious sight when it was at last set on fire. Mind you the fireworks were few, as the times were very hard indeed, being young you never realised how tough it was to just feed a large family in those days.

As children reached the tender age of fourteen it was out to work as soon as a job could be found and as time went on they were handed down to younger ones. Mine came early, a bicycle and a paper round at about ten years of age came from my elder brother who started as a butcher, a great job, as the perks came home for the pot. At school it was a bit of a battle, as I delivered newspapers at 6.30am and in bad weather I was quite often a little late reaching school by 9am. No excuses, you got two strokes of the cane, one on each hand, very painful on cold winter days. What a reward for trying to help, but that was the way it was. lt made you hurry around the streets to be on time. Four hours a day, seven days a week for the princely sum of seven shillings. lt was handed over to Ma and a shilling came back for pocket money. I thought I was well off and always had a few pennies in my pocket.

By this time about five or six kids had some sort of jobs and I suppose we managed quite well. My father and eldest brother worked at Smiths Docks, a repair yard, and until the depression set in had pretty regular work. So I suppose in the scheme of things we were fairly well off, in our expanding family. All had their little tasks to help out in the home; it would have been chaos otherwise. The smaller ones were helped and taught by those who were a few years older.

Being born seventh in a family of twelve in the 1920s was probably commonplace in those days of large families. But England, after surviving the “war to end all wars” just two years previously, was still struggling to recover and food rationing was still on. At this time on every birth registration it was stated that a ration book had been issued.

[Digital page 4, original page 4]

Even though times were very hard, and getting worse – 1926 being the year of the general strike when major civil disruption was very close – our home was a warm sanctuary in those stormy days. Without a doubt it was because of the wonderful skills and courage of our Mother.

We lived in a small community of about 1,000 people called East Howdon. This was nestled on the banks of the River Tyne and was always a place of movement – ships up and down the river, tramcars rattling by – but even in such a small place there were divisions and areas that were claimed as “ours” or “theirs”. The children in the bottom two rows of houses never mixed with the two up the bank but I think that in those days things were more centered around the home. Travel was something that you read about in storybooks. We seldom went out of our own little area and if we did we walked it – shank’s pony was the expression. All over England, villages just a few miles apart, had variations in dialect and fierce local rivalry was fought out on the soccer field, yet the whole area had a pride in being “Geordies” which still continues to this day.

I was to find that even another part of the same county would seem foreign and that they took some time to accept strangers. I refer to the small fishing village of Cullicoats in this case, which was more or less a family affair of six or seven families who had lived together for a very long time. One man who moved into the village, even after twenty years there, was always referred to as “the bloke from Wallsend” where he originated.

Still, in the cocoon of our own steadily growing family, we were secure and happy. Any problems of younger ones were quickly put right by older and bigger brothers and sisters. Responsibility of caring for the one younger than yourself was the way it worked and it worked well. The mainstay, of course, was “Ma” – feeding and looking after us all, while having a pregnancy as regularly as clockwork every two years. The logistics of washing, cleaning and cooking for such a tribe tremendous but on top of all this, she still had time for anyone else’s problems. She must have had a great constitution to keep going year after year and still be cheerful and caring. lt wasn’t a “lovey, dovey, darling and kisses” house but never did we leave the house without saying “Ta’ra Ma” and getting a reply – in fact we would stand and shout “Ta’ra” until she did reply “Ta’ra then”.

[Digital page 4, original page 5]

[Photograph with handwritten caption] TOM, JOAN, MARGIE, DON, NELL, MUM, ALMA, ANNA

As mentioned before, the rising family numbers meant that a bigger house was always a need. My first recollection of shifting was when I was about six and we moved from East Howdon to North Shields, only about two miles away, but another world. Dad worked in the ship repair yard , Smith’s Dock, so it was easier for him. We had a large, three storey terrace house, which must have had a jinx on it as we had nothing but trouble in it.

At the time, my mother’s parents were living with us. First my granddad died, then in a short time a younger brother tragically died at the age of three years after suffering a fit. The jinx seemed to be still with us as a day at the beach ended when one of my sisters and I were both badly scalded when boiling water was spilled on us at a picnic. Infection occurred and we were treated at home for many weeks, adding one more duty to our mother’s hectic life. No sooner had we got over that episode than I contracted scarlet fever. The council was putting in sewerage into the area and the fever was said to come from that operation. Being the first to succumb to the illness, I was rushed away to an isolation ward in a horse-drawn carriage and to what I thought was a prison. Parents visited once a week but they stood about twenty yards away behind large wrought iron gates while most kids wept copious amounts of tears. Also, while I was away in hospital, Ma had to cope with the house being fumigated from top to bottom. Not that it made any difference, as out of the eight

[Digital page 5, original page 6]

left at home, seven contracted the fever and had to be isolated at home for two weeks incubation period. It must have been a nightmare situation and yet she took it all in her stride.

Being part of such a large family meant you learned the rules of life very early. It seemed you always had an older sibling telling you what to do, but as you had younger ones than yourself you soon learned to pass it on to the next below you and so on in order of seniority. It must have worked okay as we seemed to be quite a happy bunch even in the worst of tough times – the years 1928 to 1939 were especially no picnic. However, we made our own fun and it all went by the seasons – each current “fad” went around in a cycle – marbles, cigarette cards, games, and rounders all came back in their own season. We were a complete clan and took care of each other.

As mentioned before my working life started when I was about 10 years old. The jobs were inherited from an older brother and I felt I was helping to do my bit. lt was hard but some things helped to make it all worthwhile, like selling newspapers to the fishermen on the large fleet which used the port. The local newspapers and a racing paper called “The Sporting Man” were popular, as the fishermen liked a flutter on the horses. Also, with the papers, I had small envelopes in which were tips from the experts, ex jockeys and trainers, “sure winners” etc. and they were good sellers at three pence each. The fishermen themselves were a grand lot of men – rough, tough, but the salt of the earth (or should I say the sea)! Many a time I would get a fresh fried herring from the cook – delicious! I was part of the scene and I loved it.

[Digital page 5, original page 7]

[Photograph with caption] In 1926 80-year-old Cullercoats fishwife, Mrs. Bessie Taylor, was still carrying her creel.

[Text continues]

The girls at the dock worked very hard gutting the herrings, packing them into wooden barrels, while salting them into layers. A cooper would put the bands and the lids on ready for loading on to ships, usually Russian or Scandinavian ones, for export. On a sunny day, it was a great sight and sound which I never tired of but if the wind turned North or South – look out, because the chill could cut your ears off even on a sunny day. However, we were used to the changes in the weather and I saw about four years of daybreaks and sunsets but I loved it and it gave me a real feeling of independence. You were responsible for getting payment from your customers and I felt great satisfaction in handing over my seven shillings wages and getting one shilling back. I also made a bit on the side

[Digital page 6, original page 8]

as Saturday extra work earned a few pennies, so I always had a little bit in my pocket.

We were still kept on the move with our increasing family numbers, and looking back we had about ten house changes over the same number of years. Of course there were no removal vans then – it was all done on a handcart, with prams, homemade bogies (a favourite with all young boys). We must have been some procession, not that that sort of thing was out of the ordinary as everyone did the same thing when moving house.

By this time though, some of the eldest had married and we moved once more back to East Howdon where we settled down from about 1935 and it seemed that at long last we would stay in one place for a while.

[Digital page 6, original page 9]

The Arrival of War

This chapter of my life is a special dedication to a wonderful mother who was an inspiration to all her family on how to cope with adversity. There is no doubt that she helped me survive the special challenges faced in battle, being a prisoner and in escaping the enemy.

The dark clouds of war were building up over Europe and I had begun my apprenticeship as a painter. For four years it meant an hour’s cycle ride to Whitley Bay, morning and night and pretty tough it was in the winter days. At times the wind would stop your riding, and a few of us would wait at a bus stop to get behind a bus for shelter and we would peddle furiously and sometimes catch it up when it stopped regularly to let passengers on or off. The exercise must have been good for us because we were hardly ever sick.

The year 1938 saw the Munich crisis with Mr Chamberlain’s famous “Peace in our time” statement but the pace of preparation for war heated up. Of course our River Tyne was one of the key docks for the building of ships so it became a real boom time. Finally, on the beautiful Sunday morning, 3rd September 1939, the somber words, “Britain is now at war with Germany”, were heard over the radio. Soon after, the wail of the air raid sirens was heard and must have been the cause of a few heart attacks. Planes had been sighted approaching the coast, and for some strange reason, the whole country had the alarm sounded but it all turned out to be a false alarm as the planes were friendly ones, so the many heart patients were probably the first casualties of the war.

After a few weeks had gone by, six of us young fellows went along to the Navy recruiting office to sign up. However, only one was accepted – because he was already working on the tugboats and they were needed for minesweeping duties. Even then, mines were being laid by enemy submarines and planes around the harbour entrance. We were told that it was ships they needed, not men, and anyway, we would soon get our call-up papers. lt was nearly five months later when I got mine and it informed me that I was to report for a medical. A quick look over by four doctors – eyes, ears etc, and if you were even at least warm, you were in, graded as “A1”.

Now came the waiting for the letter that would tell me where, when and what branch of the Armed Force I would enter. At last it arrived and I was told to report to Brancepath Castle, County Durham – the home of the Durham Light Infantry (DLI). So, with a cheery “Ta Ra Ma”, off I went to war with a brown paper parcel under my arm. Suitcases were a rare commodity in our house and, anyway, clothes would be provided. My trusty old bike was left at the station to be picked up later by a younger brother – no worries in those days of having it stolen.

We seemed to travel a long way from home, although it was only about 30 miles, but felt like a foreign country to me. The dialect was totally different, as was the

[Digital page 7, original page 10]

whole introduction into the Army, with the incessant shouting to do this and do that. The “automaton” aspect was very hard to get used to after about ten years of being independent but you had to adapt and learn quickly. Within a short period of time, we were given uniforms, equipment, and inoculations, and generally transformed into a crowd of very confused people. The loud barks of very tough-looking NCOs [Non-Commissioned Officer] then had us milling around like panic-stricken cattle.

[Photograph with caption] Bob (photo taken on entering the army)

[Text continues]

We were put into small groups and trucked away into the countryside and I finished up in a tiny village hall at New Brancepeth with about forty others. We were all shapes and sizes, which was just as well as the uniforms seemed to come in two sizes only – large or small, so swapping was the way to get a reasonable fit. We were issued with a rifle and told how to clean out the thick grease that filled the working parts. The rifle was a Canadian Ross type, left over from the First World War I would imagine.

“Take out the pull-through from the butt of the rifle” shouted the corporal -“Now take this piece of flannel and pull through the barrel to remove the grease”. As keen as mustard, I duly found the bit of string with a bit of brass on the end, gave a heave-ho and it snapped like a bit of thread. Unperturbed, I went to the corporal – “My bit of string has snapped”, I said. He seemed to swell up and went red in the face as he shouted, “You say ‘Corporal’ when you speak to me and stand to attention. I hope it is only a 2″ x 4″ flannel you have on your pull-through, if not you will be put on a charge”.

What a great start to the day, I thought. It didn’t get any better either when the towering figure of RSM [Regimental Sergeant Major] Jennings arrived on the scene. “Have the armourer push it out with the Bren gun rod” was his advice but he gave me such a scowl that I

[Digital page 7, original page 11]

knew my name had gone down into his little black book. Anyhow, they finally had to burn it out with a heated rod, so destroying any evidence of how big the cloth actually was. “What a lot of fuss”, I thought.

We settled into a frenzied pace of training that seemed to be all done at a gallop from dawn to dusk and then included some night-time exercises. The war news matched my own mood – depressing – as German Panzer units smashed through Europe, pushing the allies into the sea at Dunkirk where 300,000 men were snatched from the beaches by heroic efforts.

The threat of invasion strengthened the effort to get our training finished. This included doing guard duty on the bridges over the River Tyne that had explosive charges fitted in order to demolish them if Germany did get ashore in an invasion. Desperate times for Britain – real backs to the wall stuff. Our training finished and with six others I was sent to join a battalion, the 8th Durham Light Infantry that was stationed at the little south Devon town of Haniton. We duly fronted up to the guardroom to present our papers and were told to report to the company office on the other side of the square. Taking the short cut straight across the huge expanse of concrete parade ground, we were met by the tall, steaming figure of, … yes, my “friend to be” RSM [Regimental Sergeant Major] Jennings.

When he had controlled his apoplexy, he read the riot act about the sacrilege we had just committed, i.e. treading on the sacred parade ground. We got to know that ground very well as we joined the Headquarters’ Pioneer Platoon and my’jinx’, the RSM, was to give us a weekly dose of strenuous parade drill. Indeed, he seemed to get a great deal of pleasure as he quick-marched us up and down for two hours.

However, we settled in and found it pretty good really. The locality was very nice, but we still found it hard to get to know the ‘old hands’ who, after going through the France episode and finally the horror of Dunkirk, were, understandably, a very much close-knit team. They were also mainly Territorials so the older ones must have been together for a number of years, and even father and son relationships were common. Therefore they were a close community and it took a long time to be accepted.

The summer ended with the nightly drone of German bombers on the way to some unfortunate city. Bath, Bristol, Liverpool, Coventry all had very bad raids but it was all peaceful in the Devon countryside. We trained and prepared for the expected invasion with our Division spread along the south coast very thinly. I am sure that if Hitler had pushed ahead after Dunkirk, it would have been very hard to stop him, as the defences were very poor at the time. Christmas and New Year came and went, very subdued with the gloomy war news.

A series of intense training exercises started on the moors around Exmoor – a wild, desolate area with the temperatures around zero. We suffered quite a few deaths from exposure; even a whole crew once when exhaust fumes got under a

[Digital page 8, original page 12]

tarpaulin on their Bren carrier and asphyxiated them as they tried to keep warm after becoming bogged down. The old hands said the training was as bad as Dunkirk. Even things like evening meals brought up to us in insulated containers, may have ‘gone off’ so the result a few hours later was a severe outbreak of food poisoning and diarrhoea. Trying to shed all of your equipment in a hurry was often impossible and a lot of accidental soiling took place and all of this in a very cold, snow-covered area was, as you can imagine, very disheartening. When we finally came down off the moors we found the climate so different and people looked amazed at our appearance. What it all achieved was beyond my understanding but a lot of the army way of doing things seemed like that to me.

Although our Division was being readied to leave England for a ‘confidential’ destination we were actually issued with sun helmets. When we finally marched to the railway station, sun helmets on our shoulders, we could have had a banner flying saying “Egypt here we come”.

A long, dreary train journey to Scotland ended at Gourock where we boarded the troopship “Duchess of Richmond”. The harbour was full of ships, cruisers, destroyers, and even a huge aircraft carrier. We sailed out at dusk, comforted (in our swaying hammocks) by the large number of navy ships to protect us. The sea was calm as we headed due west and our first day out was quiet and peaceful. The “Duchess”, as was her nickname, was on her best behaviour and we sort of enjoyed our new shipboard life. However, after about 36 hours we found that all of our escorts, except the cruiser “Ajax”, had left us in the night. Rumour had it that the German battleship “Bismark” was loose in the Atlantic, in our vicinity, and when the news came of the loss of HMS “Wood” not too far away from our position, it added to our concern. As we plodded on westward, I figured we must have been going to Canada.

Shipboard life on a troopship was an eye-opener to me as a ferry ride across the River Tyne was my only previous ‘deep’ water experience. Packed in like sardines, hammocks side by side we swayed hypnotically above the mess-tables as we pressed on across the Atlantic. What a good job we were ignorant of the dangers in our journey. We were more concerned at the awful food that we had to pick up in dixies from the galley and bring to the mess desk – a juggling feat in the rougher weather. Seasickness was a real problem for a lot of men but I had a good pair of sea legs. A stroke of luck came my way when I got a job as a dishwasher in the Officers Mess. This meant that I ate with the ship’s officers and there was no swill at all on their menu. Every day I would bring some back for my mates so I was very popular when my work in the steamy kitchen was done. Huge sinks of water had steam piping to heat them, so it was like working in a Turkish bath, but well worth it.

The crew called the “Duchess” the “Drunken Duchess”, as she rolled and pitched so much. She had been designed for Fast East travel and the wild Atlantic was not her scene. But on we sailed with our lone protector, the cruiser “Ajax”, that entertained us when launching her Walrus seaplane to reconnoitre for U Boats.

[Digital page 8, original page 13]

After what seemed a very long time, we headed south into warmer climes and finally made land in Freetown, Sierra Leone, on the west coast of Africa – a beautiful harbour, but no one was allowed ashore. We were entertained by natives in dugout canoes selling fruit and shouting to us to throw coins and small children would swim down after the coins. But wrapping pennies in silver paper was greeted by howls of derision – “Glasgow tanner” they screeched. All of this entertainment was shattered by a couple of Vichy French planes dropping bombs at the convoy, but fortunately they missed.

We were soon on our way, heading south again. lt was a calm, empty sea and we crossed the Equator with due ceremony, everyone receiving a certificate from King Neptune.

It was all very peaceful and uneventful as we enjoyed the sunshine of the tropics. A day or two before reaching the Cape of Good Hope, our lone guardian, the “Ajax”, launched its aircraft for the usual slow patrol around the convoy, watched by most on board as it was a break in the monotonous routine and a welcome diversion. lt would circle the convoy a couple of times, finishing the patrol with a display, releasing a couple of balloons into the air and using them as targets for a mock attack.

It was the most exciting thing to break the monotony but on this beautiful day, the sea like a polished mirror, tragedy struck! As if on a huge stage, watched by a huge audience, the Walrus dived steeply, the wings just folded back and it went into the sea like a big dart. lt floated there with its tail clear as if embedded in the sea. The “Ajax” was swiftly alongside, but too late. We were all so sad to see it sink before a rescue could be made. I am sure the whole convoy felt as if we had lost an old friend. Just two days later we arrived in Durban.

Most places were closed as a convoy from Australia had caused some snags as the troops had celebrated in typical Aussie fashion – for example, the car on the top of the Post Office steps – but it was great just to walk along the beach.

We came across a boat high and dry on the beach that turned out to be a “city” wine vessel. There were gangs of coloured people salvaging large pieces of timber from it. Twenty or more, with ropes secured, chanted as they slowly inched the timber up the beach.

A few beers and the day was just about gone but a race back to the ship with a few other Zulu rickshaw drivers was an exciting way to finish it. The drivers were muscular, tall men in full Zulu regalia – feathers, fur, beads and all the trimmings. As they gathered speed while balancing the rickshaw, they seemed almost in slow motion as their huge bare feet slapped the tarmac but we were really motoring with three rickshaws abreast down the main street.

All too soon we were on our way again. Farewelled by the sweet singing of a lady in white standing on the breakwater as we sailed into another ocean – the Indian – and headed north to our destiny. It was getting very hot and a lot of the men

[Digital page 9, original page 14]

slept on deck as the cramped conditions of the mess decks were unbearable at times. The passage through the Red Sea was particularly awful and one of the engine room crew actually died from heat exhaustion. I think we must have been five or six weeks at sea when we made land at the bustling Port Said. We saw the sad sight of a fine ship, the “Georgio”, sunk by Italian bombers. Just her superstructure was showing and we were told that a ‘lucky’ bomb had gone right down the funnel and blown out the bottom of the ship.

Next was a train ride along the Sweetwater Canal to Ismalia. By the smell of the canal it should have been called just the opposite! So Ismalia, a sandy waste far from anywhere, was our first stop in the Land of the Pharaohs. Sand was like a dust that covered everything, even the food. Also, a plague of flies hung over the place and the thought of the clean, golden sands of dear old Tynemouth brought on nostalgia and a yearning for home.

But there was not much time for self-pity. Germany was rolling all resistance aside and they had conquered all of the Balkans, Greece and then came Crete, the latest casualty. The next stop would be Cyprus, before the rich oil wells of the Middle East. So 50 Division was off to war starting with a high-speed dash to Alexandria on one of the Navy’s fastest ships, the minelayer “Orduna”, said to be able to travel at 40 knots. From Alexandria to Famagusta and a hectic landing in the middle of the night saw us scrambling down rope nets with a few bits of equipment lost between ship and jetty. They said that the ship had to leave before daylight, as enemy bombers were a daily hazard.

Headquarter Company settled in at the capital, Nicosia, a lovely old city that I got to know very well. Our tents were pitched in a groove of very old olive trees – quite pleasant, and we soon settled down. The weather was fine and, being scattered around, we weren’t under the eagle eye of RSM [Regimental Sergeant Major] “Spike” Jennings, so that was a nice change.

The Pioneer Platoon was a mixture of all trades and one of our duties was seeing to the burial of any dead. Nameplates had to be made for coffins and this job often fell to one of our Lance Corporals who had worked for the Co-Op Undertakers back in his hometown. He was appropriately named Ted Toll – after “For Whom The Bell Tolls”.

I remember a time we had to take a coffin to the mortuary in Nicosia when one of our dispatch riders had unfortunately been killed in a road accident. He had run into a horse-drawn carriage at night and the shaft had hit him right in the chest. So after we had got his nameplate done, off we went to the mortuary to box him up. When we arrived and had him laid out, we found that no one had brought along any tools with which to screw down the lid so we hammered in the screws with the butt of a rifle. Well, the joints on the coffin lid were filled with what seemed to be wax that, with our strenuous blows with the rifle, were soon jumping out. It was impossible to get the screws down flat so we just left them sticking out a bit as the men doing firing party duty had arrived. I often wonder if this was noticed – certainly nothing was said.

[Digital page 9, original page 15]

One of our other less morbid duties was brothel patrol. Essentially this involved checking out that lower ranks were not in the higher-class “Officer Only” establishments. lt was certainly an eye opener for me.

We had about five months of an almost peaceful time on Cyprus, broken by daily high altitude bombing by Italian planes – only specks in the sky, but pin-point accuracy with the airport the target. Occasional trips across the Troodos Mountains to a beach at Kyrenia would mean a hair-raising bus ride over hairpin bends and sheer drops. The driver seemed to spend most of the trip with his hands off the wheel, which didn’t help, but the beach was just fabulous. Clear, buoyant water was a welcome relief from the very hot weather.

[Digital page 10, original page 16]

Off To The Middle East

However our idle life would change very soon. On the 5th of November we were taken by landing craft to scramble aboard the destroyer, HMS Hasty, for another dash across to Haifa and into the Holy Land where we came under India Command. Apparently General Wavell had ordered that we were to be toughened up after our soft life on Cyprus – so daily twenty-mile route marches with full kit began. Our troop carriers took us to within twenty miles of our camp, then set us down to march home. This occurred all the way through Palestine, Jordan and Iraq where we finally finished up. The northern city of Mosul and the oil wells of Kirkuk were of course Germany’s Middle East target and they were fairly close having reached Sevastopol. Luckily for us, the severe winter was to hold them up. We were in tents and felt the dramatic change in the weather badly. By early December, the snow was so bad that the pickets had to patrol at night and rake the snow off the tents to save them from collapsing from the sheer weight of it.

At that time we were trying to kid any would-be-spys that we were more than one division by periodically changing our division signs on our wagons, so I was pretty busy. Our TT sign was painted onto a piece of steel and slotted into a groove on the front of the trucks. A new one was on the back, 62, and on certain days would be changed over in an effort to confuse. But it was such a desolate part of Iraq I wondered where the spies could hide! Admittedly, the locals were not very friendly so any of them could be “agents”.

Sometimes I did get a trip or two to buy supplies of paint in Mosul, and the sights I saw were like something out of the Dark Ages. Slaughter houses seemed to be a common feature in the streets – sheep, goats, camels were killed by a man who decapitated them with a two handed sword and the smoky fires were, I think, to keep the black clouds of flies at bay. lt was like a scene from Dante’s “Inferno”. However, overall I found Iraq a bleak, barren land and was glad to leave in early February, bound for warmer climes. lt was a much quicker trip back down through Iraq, Jordan and Sinai to cross the Suez once more near lsmalia and again taste the sands of Egypt.

lt was a very barren, cold country with only the rich oil deposits making it such a prize for the Germans. Kirkuk was the town where the oil pipeline started, stretching all the way through Iraq, Jordan, and Palestine to Haifa, so it was a glittering prize for the Germans to try and break through to. They almost made it at Sevastopol, however like that other invader, Napoleon, they were stopped by the cruel Russian winter.

lt was a miserable time sleeping in tents with snow and freezing temperatures. At night it was necessary for tents to have the snow raked off to stop the weight of it collapsing them – after the heat of Cyprus we all found this very hard. Also, our

[Digital page 10, original page 17]

clothing was not suitable for such conditions, just the normal battledress and greatcoat.

Christmas came; a bleak and freezing day, but the cooks did well with the meal served to us (sitting in the backs of our transports) by the officers – a tradition of the Division.

[Photograph with caption] Christmas dinner

So it was with no regret that we once again loaded up the camp and set off for warmer climes. A quicker trip back – no daily marches – and we were once again over the River Jordan into Palestine. A stop on the way beside an orange grove saw the trees almost picked clean in record time. Oranges had not been on the menu for months and this variety, Jaffa, was the best!

We continued across the Sinai desert, across to Suez, and back into Egypt where I celebrated my 22nd birthday just outside Cairo. We were lucky for once to be camped near a huge hotel and so beer cans were built into a mini pyramid – a birthday to remember.

Soon we were on the coast road again via some famous places; Mersah Matruh, Sollum eh Adem and Tobruk. Names we were to get very used to, and finally into the front line to relieve the 4th Indian Division at Gazalla – not a town but a stretch of barbed wire and minefields. Life was soon marked by stand-to at dawn and dusk, and the occasional hair-raising exploits of the Pioneer platoons that were trying to clear the minefields at night. The sappers would try and plot out where they thought the mine grids were set, and then at night they would probe and defuse them. lt was bad on our nerves – goodness knows what it was like for them!

[Digital page 11, original page 18]

[Map with caption] ROUTES FOLLOWED BY THE 8TH BATTALION IN THE MEDITERRANEAN THEATRE

[Text continues]

The weeks dragged on and, in May, I came out of the draw for seven days leave to Cairo. Three of us left by lorry to Derna, then a rattley old train with cattletrucks for accommodation to El Alamein. Then a normal train (wooden seats) for the rest of the way. The journey took a day out of the week so we had to make merry with just five days and a trip to the pyramids on the first day got our sightseeing over with. They were a wonder to behold even if the Arab guide wanted paying every time he lit a sparkler type of illumination – hadn’t heard of torches I suppose. The trams looked like travelling hills of people, so many were clinging to the sides and they rattled and swayed at an alarming speed. Inside, you were packed in like sardines and smelled much worse. When one of the lads got off, he found that his pay book etc had been stolen even though his shirt pocket had a safety pin through it to secure it. lt took us half a day at a military police barracks to get it sorted out, as a very serious view is taken because a pay book was like a passport and evidently brought a high price on the spy market. A glorious few days in the teeming city and then we were back on the train all too soon. We were greeted at the lorry pick-up by a fantastic sandstorm. Impossible to see your hand in front of you. We crawled along for two days of sheer torture and made it through to our battalion.

It was this sandstorm behind which Field Marshall Rommel pushed his advance deep in the desert and by-passed all of our coastal defences before turning in towards Tobruk, leaving us surrounded. Sadly one whole brigade (150th Brigade

[Digital page 11, original page 19]

of the Green Howards, East Yorkshire) to the left of us was decimated when the Germans bombed and punched through with his heavy armour.

At this time, part of our duties as mine clearance was to take charge of a gap in the minefields to allow exit and entry of patrols. This was a one-man duty of 24 hours that came around every two weeks. Everyone was pleased to get it over with as you were alone with the nearest friend about half a mile back. You had phone contact but it always seemed a long 24 hours.

One evening at stand-to after doing my spell at the “gap” a few of us were talking amongst ourselves regarding how our water ration was being wasted in making tea. lt was so heavily chlorinated it was impossible to drink. We opted to get a Corporal to ask for the water to be given out instead as we used to dose it with Andrews Liver Salts and it went down well then. What we didn’t realise that all our discussions or arguments had been overhead by the CSM [Company Sergeant Major] and the QSM [Quartermaster Sergeant Major ?]. The next morning I was surprised to be called out by the CSM [Company Sergeant Major] and told to report to the Company office dugout. I was marched in to face the Company Commander and just about fainted when the charge was read out – all sorts of things tantamount to inciting mutiny in the field, a court martial offence!

“What do you have to say for yourself”? I was asked. I tried to explain about the undrinkable tea but was dumbstruck by the severity of the charge. With dire threats of a court martial and of being surrounded by the enemy, I was sort of released on parole to be of exemplary behaviour – or else! I retreated to my dugout that I shared with Johnny Mellor to ponder my misfortunes.

The following morning I was greeted by my “friend”, CSM [Company Sergeant Major] Wood, told to get my kit together and go on outpost duty again. My protests that I had only just done duty two days ago, were brushed aside with another threat of failing to obey an order and further dire consequences. My own sergeant could only say, “Do it, and we shall protest later”. But “later” very nearly did not come about. Even though I felt that it was a clear case of someone in authority trying to get back at me there was nothing to be done about it so off I went. The man I relieved was proudly waving his wounded hand. “What did you do, kept it poked up out of the slit trench?” I asked. “lt will keep me away from here for a while” was his cheerful farewell – “it has been pretty hot around here lately”.

After an hour or two watching a huge Mark IV Jerry tank patrolling back and forth to the entrance of the valley, I was amazed to see a convoy of trucks drop off at least 200 infantry just a few hundred yards in front of my post. A frantic phone call told me all was under control as they were about to shell the enemy with a barrage of 25 pounders and mortars. So this kept me entertained until dark.

Come daybreak I was told to lift the mines in the gap and to go out with the patrol to round up the prisoners we hoped were going to surrender after the heavy barrage. Down came a bren-carrier, an armoured car and a 15cwt lorry, into which I climbed. We had no sooner cleared the minefield, than up and out of a

[Digital Page 12, original page 20]

fold in the ground, rose at least 150 Italian soldiers who formed up in good order and advanced towards us. Guiding them through the gap, we just pointed to the rear and off they went. After salvaging an anti-tank gun and a couple of shellshocked Italians, one who was able to hang onto the tailboard of the truck whilst standing on the limbers of the gun to stop it bouncing around, we headed back.

After all the excitement I was left at my lonely outpost to await my relief at midday. Noon came and went with no sign of anyone. Apart from the shelling that mostly went over my post, it was peaceful until late afternoon when five enemy fighters tried a shooting exercise at low level. I could see the pilots clearly, but clearer still was the row of flames from the wings and I was the only thing in sight apart from an old Italian gun, with a pile of ammunition that we hadn’t a clue how to use. After each plane had a turn at firing at me, they formed up as a unit and the five, side by side, roared down this little valley with guns blazing. How so many bullets could miss me, I’ll never know as they pinged off stones and the old gun as I lay crouched in my shallow slit trench with my blanket folded and placed on my back in the hope that it would stop a bullet. Not a scratch did I get, so I surely must have had a Guardian Angel looking after me.

Dusk was coming on and I had no word of relief and as my 24 hours rations had long ago been eaten, I was starting to get worried. The phone link with the outpost had long gone dead.

I decided to have a walk back and check the phone line that may have been put out of action with the shelling. So, leaving everything except my rifle and ammunition, I picked up the line and trudged off to investigate. Lo and behold, I arrived at a deserted and empty outpost and felt as if I had been abandoned on a desert island. Feeling dismayed and really isolated I was unsure as to what to do next. To leave my post could be another disaster for me if by some chance, my particular gap was still needed. The outpost was a slightly elevated pimple on the flat desert and there I stood, a lonely figure, peering into the falling dusk.

I could see a lot of activity, like dust rising from lorries, back towards our main defence lines. Suddenly a bren-carrier appeared, travelling fast towards me and I thought – “now I shall get some news”. lt was the battalion CO [Commanding Officer] and his entourage crammed into the carrier (but I was sure that a little skinny guy like me could fit in).

“Who are you and what are you doing here?” were his brusque words. I explained how I was in charge of the gap and that I had not been told to leave. “Humph” he snorted as if I had made it all up. “You should have been out of here at first light”.

Wish I had been, I thought to myself.

“Look across to where those trucks are,” he said, “that is about the last of the battalion. We are abandoning the area, so hot foot it over there and get aboard any lorry you can”.

“What about all my equipment?” I cried. “Never mind that” he said, and with that roared off and left me standing there.

[Digital page 12, original page 21]

Great! Nothing like a good hike on a starving stomach. Why he couldn’t have given me a lift I do not know (I would have climbed up the radio antenna at a pinch). But, no, I was on my own again. Off I went at a gallop and as it was getting dark by this time, I was more than a little anxious.

Eventually I reached the passing trucks but to my dismay the first few refused to pick me up. They said that water had been rationed to each man as the plan was to punch through enemy lines and head deep into the desert before turning back to the coast at Mersah Matruh. “Thanks very much” I thought. My own water bottle was as dry as the desert.

After being refused by a few more “comrades”, I got a “Yes, climb aboard”. They meant me to clamber on top of the canvas cover but I scrambled up the camouflage netting. lt was quite comfy-like a hammock-and a bird’s eye view of the battle. Little did I realise it, but I was sitting on top of a virtual bomb! The truck was full of 4-gallon petrol tins. The driver shot out of the column into the darkness with a yell from his mate, “lend a hand to dump some of these tins”. We stopped and started piling up a half dozen cans. The driver shouted, “climb aboard” and fired his revolver at the cans until they burst into flames. Off we roared and in a flash tracer was flying past to where we had set the fire. Through the columns of trucks and out to the other flank, we repeated the same ruse. lt was getting too hot for me and when we rejoined the rest of the column, I dropped off to become a foot soldier once again. The nightmare continued until, at last, I recognised a friendly face on a truck – our own company wagon. The CO’s [Commanding Officer] clerk, a Newcastle lad from Percy Main said “get in if you can” as it was pretty full. I was perched on the tailboard when a shell landed really close, the blast nearly putting me in beside the driver. However, no damage was done although the noise and confusion was bewildering. At least I was with my own mob – or so I thought.

At another stop as we went through more Italian lines, I heard a voice I had come to loath, demand from the back of the truck “Who are you? You will have to find your own truck. I have prisoners we must interrogate”. lt was, of course, RSM [Regimental Sergeant Major] Jennings, my nemesis, so once again it was out into the confusion and darkness to try and get a truck to get on.

Finally, a signals truck let me get aboard and bliss! It was great to find a 44-gallon drum of water with the bung out and a copper ariel to suck it up with. I had come to Shangri La after a nightmare of two days that I should never have been subjected to. After forty-eight hours travelling we turned north to head back to the coast at Wadi Mersah Matruh. Digging in, we had one quiet day before the shelling started again. The Company was asked to send a truck into the town as the NAAFI [Navy, Army and Air Force Institute] was to be destroyed and we could procure supplies before they blew it up. We received a shared out portion – two beers, 50 cigarettes and a few boiled sweets per man. We thought it was buckshee but it was deducted from our first pay at El Alamein – a great way to sell something earmarked for destruction.

[Digital page 13, original page 22]

Rommel was not going to let 50 Division off so lightly and by nightfall we were once again surrounded and were taking heavy shelling. A lovely full moon lit the desert like daytime and again we formed up into a column to breakout through the German lines. We stripped off the canvas tops from our 3-ton lorries and everyone sat up without any steel helmets on, to pretend that we were Italian or German infantry. We even tried tying on a bush to the tailboard as the Germans did. At that time the Germans used a lot of our captured trucks so we were (cheekily) hopeful of pulling it off.

All went well and we passed through the lines with only a few tanks and lorries lagging behind. We made the open desert successfully, however the Padre’s and the Second in Command’s trucks were hit when enemy guards opened up. No further trouble came our way until just before we came up to the wire that marked the Egyptian border. In a short, but fierce, tank battle our Honeydews suffered heavy casualties against the much heavier German tanks.

[Map of battle with caption] GAZALA ROMMEL ATTACKS, MAY – JUNE 1942

THE WESTERN DESERT. The line-up of the opposing forces at Gazala when Rommel attacked in May 1942, and the break-out route taken by the Battalion a few weeks later, south of Bir Hacheim and back to the frontier.

Next stop, a patch of desert near El Alamein station for organising and replacing to bring the battalion up to strength. A grand parade of all the companies in the battalion was arranged for us to be inspected by General Ritchie. As I had lost my kit and all of my equipment, the only clean shirt I had was a German one that I had picked up from somewhere. We fell in with full service marching order (FSMO) of course. The only formal FSMO I had was rifle, bayonet and ammunition pouches (four) so I was covered up with them. Inspection by the Sergeant and the CSM [Commanding Sergeant Major] raised no eyebrows but then came a last check-over by

[Digital page 13, original page 23]

my friend! Yes, RSM [Regimental Sergeant Major] Jennings gave me a screaming session. Fit to burst, he ordered my dismissal from the parade, which pleased me no end as it was a red hot day and we had been standing on parade for well over an hour. Two hours later, after many men had fainted from the heat, the platoon trudged back to our tent saying that I would be for it, but that would be nothing new to me.

Although I never heard anything more of it, the feud seemed to carry on and ultimately myself and a couple of others were transferred out of HQ Company into B Company (a rifle company). That was a real shock to the system, as we had been in HQ together for well over a year. So it was straight into training on night manoeuvres to get us sorted out.

We had one pass to Alexandria but had to be out of the city by 6pm. The locals acted as if the Germans were due at any time. On 23 July we got orders for a night attack – a “simple” straightening of the line, capture a bit of a ridge and wait for our armour to consolidate.

I didn’t fancy it very much, especially when the padre came around and held a bit of a service and also dished out cigarettes and a few boiled sweets. Night-time saw us trucked forward to our start zone and another bit of a shock when we lined up – the first order was to fix bayonets. That got the short hairs rising, especially for some of our replacement men, some of whom had been rushed through the Mediterranean and had only landed in Alexandria a few days ago.

The Sarge said that it was OK as the artillery was going to give the enemy positions a good pasting. lt was certainly noisy and we all thought that nothing could stand such a pounding. All went quiet and we were told to move forward. I wasn’t really scared as we were in the second wave of men. However, no sooner had we started forward than heavy machine-gun fire and anti-personnel shelling became very heavy and men were being hit all around. A lot of barbed wire was holding up the first wave and we closed up behind them at a marked mine field.

The officers were having a conflab behind the wire for a while, and then our CO [Commanding Officer] stepped over and led us forward to take over as front-runners up a rising slope that seemed to bristle with well-fortified positions. Despite us suffering a lot of casualties, we reached the dug-in enemy troops and they came streaming out to surrender. A lot never got the chance as in the dark and after the punishment we had taken they were mostly shot down.

We finally reached the top of the ridge and started to dig in to await our reinforcements of armour. Spasmodic shelling continued throughout the hours of darkness. Two half-tracks, mobile guns similar to a Bofors, drove close to our positions and laid down fierce fire until both were knocked out with our 2-inch mortars. At first light we watched enemy lorries coming down a forward slope and go out of sight in a fold of the ground. The next thing we saw was the Infantry advancing at walking pace towards us – it was like a clay pigeon shoot and they soon beat a hasty retreat to a flurry of shots as they climbed into their transport. Still no sign of our relieving tanks. We could hear plenty of cries from

[Digital page 14, original page 24]

the wounded and one man, lying out in the open in front of our positions, kept waving and calling. Someone said he is shouting “DLI” (Durham Light Infantry).

Along came CSM [Commanding Sergeant Major] Ralston -“You and you” he cried, “have just volunteered to go out and bring in that man”. Naturally it was firstly me who he was speaking to. We scuttled away. It was all very open with still a bit of shelling and the odd burst of small arms fire. When we got up to the injured man, he said that he was called “Brown”, a 9th Battalion man and had been hit the previous night. He had been a prisoner on a Jerry truck for a while but, for some reason, they had dumped him off during the night. He had small wounds all over his legs. We carried him on a rifle between us and, with his arms around our shoulders, dashed back to our position. I then helped make him a bit more comfortable and used my own field dressing on his worst leg wound. What a mistake that was, for when I got hit later on – and asked the CSM [Commanding Sergeant Major] for a replacement dressing you would think I had committed a hideous crime.

However, all his ranting was a bit wasted, as we were soon to find out. When dawn roll call came we found that only 32 of our original 90 soldiers were left alive and uninjured from the previous day – a very bad night indeed. To make matters worse, with the morning came the enemy. With an ominous clanking and roar of engines, five Mark IV German tanks came down both the forward slope towards us and from our rear. A furious barrage roared over our heads, as the artillery did its best to knock them out. However, the tanks had a charmed life amidst the shell bursts. Even though there were no hits the intensity of the barrage turned them back. This action was repeated two or three times but eventually the tanks came directly at our line in single file and broke through one end of our thin defences. The shelling had to stop then and that was it! We were prisoners.

[Digital page 14, original page 25]

In the Bag

It didn’t seem real somehow and we all just stood around in a daze whilst these huge tanks rumbled over our hastily dug slit trenches. The tank commander waved us back towards the German zone and made us gather up all of their wounded. We laid them on the back of the tanks before we were herded back to their own defensive line.

Huddled together we sat on the ground and spent a miserable day pondering our fate. During this time we were subjected to spasmodic shelling from our own guns – not a very pleasant experience. By nightfall all of our food and water had gone and there was no sign of any forthcoming.

Apprehension was felt by all when we began to be split up into small groups of up to 8, 10 or 15 people and under guard, marched away into the darkness – with guards all carrying automatics or light machine guns. Fertile imaginations had most of us thinking that we were to be taken away and shot. This was reinforced by the incessant rattle of machine gun fire all around us. Our turn came and about eight of us from B Company, including Bill Alcock and Johnny Mellor my two mates from HQ who were transferred with me, climbed aboard a 30cwt truck with two very nervous guards. Off we went into the darkness and after a jolting ride over the desert we eventually hit the coast road and finished up on the beach at Derna. Here we managed to fill our water bottles and also, under guard, had a swim in the sea. There were some tents on the beach and as we passed one it appeared empty except for a table with bottles standing on it. Bill Alcock spotted an opening in the tent wall and, as quick as a flash, he reached in and grabbed a bottle. But to our dismay it turned out to be Vichy water. What a let down.

So there was no grub at all that day. But next day, in Tobruk, we got our first ration of corned beef and biscuits. From there we were packed, standing room only, on to big lorries with trailers for a gruelling journey, with no stops for toilet emergencies. These were ‘managed’ somehow as we went along. This was much to the amusement of our guard, who sat perched on the roof of the lorry and fired shots close to our heads just for laughs.

At long last we hauled into a camp, nicknamed “The Palms” – an exotic name for the most dismal piece of Libya that you could imagine. Just a wadi with barbed wire around its steep sides and, across the mouth, a crude gate of the same material. Guarded by trigger-happy Italian soldiers, it had no water, shelter or any amenities and the toilets, dug into the wadi sides, were soon overflowing as about 2000 men were crammed into its stinking confines. Water and rations came in once a day – a tiny tin of some sort of watery, stringy meat, between two of us, and a small loaf to be shared between four. The loaf seemed to be made up of 50 percent sand and it ground down our teeth whilst trying to eat it.

[Digital page 15, original page 26]

One day, two enterprising Kiwis got under the lorry and, clinging to the chassis, got clean out of the camp. Unfortunately for them they got off just in view of a group of soldiers. When they were brought back, the major in charge had them hung up, with their hands behind their backs, to the posts on the front gate and so stretched that they were up on their toes. After a few hours in the searing sun, both men collapsed and it was pitiful to see them hanging like corpses. A crowd gathered and shouted abuse at the guards until a sympathetic one put a rock under their feet so as to ease the strain on their arms. The Italian major in charge came on the scene and immediately called out the guards who set up machine guns facing the crowd at the gates. He could speak English and said, “Get back or I will open fire”. A most undignified scramble took place as it looked as though they meant business. A short time later, however, the two were taken down and put in the guards’ tent and even given grapes and wine before being returned to the cage.

[Digital page 15, original page 27]

“Cruising” on the MV Nino Bixio

After two weeks of miserable existence, we were glad to be told that a ship or ships were to take us away to Italy – another adventure I will never forget. Loaded once again like cattle, onto the huge lorries, we were tormented by the Italian Colonial guards from Eritrea I think, as they demanded any rings or watches. Anyone who still wore them were pounced upon and dealt a nasty smack with the butt end of a rifle to make them hand the valuables over. We were pleased the journey down to the docks was not too long and soon we could see a fine looking ship alongside the quay.

lt was the Italian Motor Vessel (MV) “Nino Bixio”. The harbour bore the scars of bombing along with quite a few wrecked and sunken ships. We were soon loaded aboard and before disappearing into the holds two or three of us hung back to have a scrounge around and snaffle anything to eat. We made contact with the cook who could speak English, but no luck with any grub. We were getting used to doing without by now. Anyway, before long we were rounded up and prodded by excitable Italian guards and pushed down No. 1 hold to begin our Mediterranean cruise.

[Photograph with caption] Nino Bixio: ‘The beautiful ship who would not die.’

Our scrounging delay may have backfired on us because when we were pushed into the hold it was to find no space at all on the upper part and so had to find space on the bottom. About 500 men were crammed into the semi-darkness with only one corner of the hatch permitting a little light. Hardly an inch of space was left and we finally had to settle in the farthest corner. There was no room to lie down so we just squatted in the gloom with the increasing stink of men almost all suffering from dysentery. A 40-gallon drum lashed to a steel post was to be

[Digital page 16, original page 28]

used as a toilet as not all the men were able-bodied enough to climb the two vertical ladders to the deck.

We set sail at dusk and the sound of water swishing by did little for our morale. Soon the drum of excrement was overflowing and the stench was almost unbearable. Some tried to carry tin hats filled with it up the ladders – a tricky job at any time, never mind on a swaying ship under way. The howls and curses as a rain of stinking fluid soon put a stop to that. Daylight filtered in from the one open corner, not that it reached us in the far corner.

I decided to go and try to get a breath of fresh air. The guards allowed about a dozen men to come on deck to use a makeshift latrine that had been built over the side of the ship. lt was a crude affair, basically a trough with permanently running water washing the waste straight into the sea, and just a rail to perch on and another to cling to. At least it was clean and the view was great. I was in no great hurry to go back down to such misery. The sun was beautiful and the sea calm and a brilliant blue. We also had an escort of two or three Italian Navy ships fussing around. Eventually I was chased off my perch and back to the hold. Just as I was being pushed below decks, I noticed a lot of the Italian guards had lifebelts on. Even so it didn’t overly worry me.

My mate Johnny was dozing, so I went into the queue to fill up my water bottle. A single tap dribbled slowly and a wait of an hour or more was normal. Eventually I managed to fill the bottle and my enamel mug. I was just putting it to my lips ready for a welcome drink, when BOOM! There was a sound like a huge steel door being crashed shut, and in an instant the sea was filling the hold and I was lying flat on my back with something pinning me down. Even so, my mind was still working and the silly thought in it was “I never did get that drink”. That was soon to be remedied but the water was a bit salty, as well as whatever else was mixed in it.

A British submarine had torpedoed us and the surge of the sea coming through the huge hole in the bow of the ship was swirling everything around. The ship was still going ahead adding to the surging and we were all being tossed around with it. Whatever had pinned me down was swirled away so I tried to get to the surface. No great swimmer, I kicked madly to try and get up, but my breath was gone and I could feel the water going down my throat. Suddenly I popped to the surface, but immediately went down as the water filled up to the steel plates of the upper part of the hold. “Blast” I thought, “I never got a breath”, but up I popped once more. I was about twelve feet from the side of the hold and the water seemed to have turned into a thick horrible brew.

I almost scrambled over the top on hands and knees, and even at such a time I thought “Jesus walked on water” and I might have done so too. As I reached the side another man was clinging to the wood slats that ran around the hold. He was clinging to one side of a lifebelt and I clutched at the other and for a short time we struggled for possession. As I was still in the water he had an advantage

[Digital page 16, original page 29]

and I gave up as another surge covered me again. Clinging to the slats I noticed that the other man had disappeared.

I was in a corner which was filled to the steel deckhead every minute or so, but as the ship slowed to a stop I could take stock of my predicament. I was in the top corner of the hold with three sides of steel plate around me. One of them was the bulkhead between Holds One and Two. There was about two feet of air space available that at times disappeared altogether as the ghastly brew sloshed back and forth with the motion of the sea. I was feeling pretty desperate when I noticed that the bulkhead between the holds had a gash torn in it by the force of the explosion. The gash was about six feet long and maybe a foot wide and, luckily, only about five feet away from me.

Clinging with one hand I could just reach it but as the water surged it went through like a huge waterfall into Hold Two. To be caught by such a torrent would be suicidal so I had to wait for the water to settle. At the same time I was fearful that the ship would sink, so I knew that I had to time my move just right. I spread-eagled myself with one foot in the gash and one hand on the wooden slats. I let the water cover me once or twice as I timed the surge and then swung into the gash – clinging to the jagged steel on the other side I swung once again on to the ribs and I was into Hold 2.

I was somewhat better off as only about four-foot of water was sloshing around the bottom with a few bodies floating in it. The hold had held about 500 Indian troops and they were fighting to climb up the two ladders to get on deck. The ones on the ladders were being crawled over by other men, so it took some time before it cleared. Anyhow I was in no fit state to do any fighting. Just then I took stock of the situation and found I was stark naked apart from my shirt collar and two pockets -every stitch of clothing had been blown off me. When I finally stepped out of the hold I was horrified to realise that I was standing on a half a man, severed at the waist. I got rid of a lot of seawater and foulness as I wretched and heaved.

But I had to think about my chances if I was to go overboard. First things first – clothes, water and then I would think about what to do. I quickly got my bearings and found the crew’s mess that still had food on the plates. I grabbed a chop and scuttled into the crew’s cabins grabbing a shirt, shorts and a cardigan (German by the colour I thought). Get going I thought, when a large, angry gentleman came at me screaming and flailing his arms. I ducked and ran clutching my or maybe his, clothes and out onto the deck.

It was a real nightmare in the sunshine of that August day. The bodies lay in heaps and the wounded were just pitiful. I wandered in a daze looking for Johnny and my other mates but found none of them. The ship had quite a list and a lot of men were throwing things over the side.

[Digital page 17, original page 30]

I saw a medical orderly I knew, Ginger Rutherford. He was doing his best to help the pitifully wounded. “Can I do anything?” I asked. He said “Go and try and find anything to bandage them up with – sheets or such like”. Back I went into the tents crews’ quarters and grabbed sheets, pillowcases and found a cupboard with cigarettes and a lot of boiled sweets. Stuffing them all into a pillowcase I was out on deck once more giving a fag to those whom were critically injured. lt seemed to help them as they passed away. Ginger said to me “There must be every injury known to medical science here around us”.

The ship was listing but the danger of sinking seemed to have passed. Possibly the fact that two torpedoes, one in the engine room as well as Hold 1, may have stabilised the ship. However, it was going very badly for all the poor souls who had jumped overboard. Our Italian Navy escorts must have made contact with the submarine because they started depth charging. As a result the people in the water seemed to just disappear. All this time the sea was calm, and brilliant sunshine shone down on a shattered ship filled with shattered bodies.

The torpedoes had struck at 3.17pm and the shadows were becoming longer as the Captain tried to rally his crew and get a towline on board from one of the Naval escort ships. It was dark when we commenced to limp towards the coast of Greece. Exhaustion had caught up with me and even though a nasty gash on my forearm was throbbing, I still fell into a restless sleep amid all the carnage on the deck.

Daybreak saw us in sight of land and by noon we wallowed into the picturesque little harbour of Navarino. The towing ship made a sweeping turn and dropping the line, allowed the “Nino Bixio” to gently come to rest on a little sandy shore. I was feeling rather off at this time from a combination of shock and a raging infection from my injured arm. The ship was soon crowded with newsmen eagerly photographing the carnage, much to the disgust of the Captain who ordered the press off his ship.

All of the wounded were soon put ashore and I followed with those who could walk. We finished up in what I thought was a school. It was soon filled with the moans of the badly hurt men – many died during the night. It was a two-storey building with wide concrete stairs and space was at a premium. So much so, that every step had a wounded man on it. I spent most of that night helping men down to the ground floor where treatment of a sort was carried out.

Some time during the early hours I had my arm dressed. A young Naval orderly gave me the works. When he jabbed a swab into the gash, the top of my skull just about came off. He consoled me by taunts of “Wadya tink of di British Navy now, eh”? I was past caring about any Navy as the last 48 hours was about all I could take.

A feed of rice of some sort was passed through the bowels untouched like rapid-fire machine guns. The toilets, a hole in the concrete with footprints, gave you a picture of the action, dysentery still being rampant.

[Digital page 17, original page 31]

The walking wounded had to help one another and in the few days that we stayed in Navarino we had to trudge out to an open field that was set up with tents as an emergency treatment centre. On one morning as I was being checked over, I watched a Sikh soldier with a head wound crying his eyes out as a rather sadistic orderly took great pleasure in chopping off the Sikh’s hair. It was about 3 feet long and as he cut it off he cruelly dropped it into the sobbing man’s lap. Sikhs, I believe, never cut their hair and it was pitiful to see his distress.

[Digital page 18, original page 32]

WHY?

It will be sixty years on 17 August 2002 that so many lives were lost in a single moment when the “Nino Bixio” was hit by two torpedoes from HM Submarine Turbulent under the command of Captain “Tubby” Linton (VC) [Victoria Cross]. In a single moment as many as 400 perished. I have told my story earlier but what I want to record now is the tragedy that befell so many other POWs who died unfortunately at the hands of the Royal Navy.

Let me say now, I never heard anyone ever say a single word against the Navy. The general word was, “that is what their job is” but it is such a shame that so many had to die. Ever since the “Nino Bixio” incident I have heard a lot of stories of different ships being sunk and the awful waste of lives. Being crammed like animals in a stinking hold is an awful defenceless way to die. If the “Nino Bixio” had sunk, the toll could have possibly been around fifteen hundred to two thousand. To survive two torpedoes is a miracle for a vessel. I have reasoned it to myself that being empty saved her and a forward hold and the engine room kept her afloat with her other holds intact. She was tough and in the last few years I have found out her history when she was beached in Navarino, Greece she was patched up and towed to Venice and sank as a block ship there.

After the war she must have been salvaged and repaired. Under the same Captain, she visited Wellington in New Zealand, and he opened the ship for all survivors to visit her. The Captain was a fine man who unfortunately died the following year, 1959.

The reason I bring such a sad tale to light is the huge waste of men who died. Could it have been avoided? Usually ships returning from Africa were empty apart from the pathetic human cargo, and surely the naval intelligence must have known that POWs were being loaded from African ports. But it was not an isolated incident as at least seven or eight ships were hit.

According to a military historian for the British Army, the El Alemein War Memorial has about 11,000 names. Of those, it is thought nearly 7,000 died as POWs. Tragic is hardly the word to describe such losses. I have had documented proof of a single ship the “Scillin” sunk by HMS Porpoise that one thousand men died in a single hit. She was a small ship, quite old being built in Scotland in 1903. The submarine surfaced in darkness and shelled it until it stopped, torpedoes sank her in minutes and as the “Porpoise” sailed through the flotsam, a lookout heard a voice in the dark. He shouted “any English there?” “No, but there’s a bloody Scotsman”. He was one of the lucky ones, twenty seven, including Italians, were hauled aboard before an approaching enemy vessel made it submerge.

Of course these events in wartime are never revealed to the public. It would have been bad for morale but I do think these disasters could have been in some

[Digital page 18, original page 33]

cases been avoided with a bit more care and knowledge of sailings from certain ports in Africa, especially Benghazi. That is the sad case of the effects of what has before known as “friendly fire”.

Even boarding the ships in Benghazi was a lottery of fate – embarkation cards had been issued at the prison camp, colour coded for the different ships. Consequently mates exchanged cards in order to stay together. Some to miss disaster completely, others to become traumatized, wounded or die. But life is like that – mine would certainly be different if my sisters, on my return from Switzerland, had not told a local Newcastle newspaper reporter of my “torpedo” exploits. When the article was published a few days later, there were dozens of letters begging if I knew of any their loved ones missing as POWs.

A strange twist to the tale of my time on the Nino Bixio occurred about three years ago when a man who was on the second ship of the two that sailed from Benghazi, the Siestre, claimed that the torpedoes that hit the Nino Bixio were actually aimed at the Siestre. Apparently the crew spotted the torpedoes and evasive action avoided contact. The Siestre arrived safely in Italy.

The eventual fate of the Turbulent was not so lucky. Having escaped the torpedoes of the escort ships she was lost with all hands in April 1943.

[Digital page 19, original page 34]

A Prisoner in Italy

After a few days in Navarino we were bundled into railway wagons – fifty to a wagon – with about ten wounded and forty of the Indian soldiers. We only stopped once, on a deserted stretch of line, for a toilet call. The guards were Italian Blackshirts and didn’t mind helping the slower prisoners back aboard with a boot in the behind. One of our lads, Oxley from Gateshead, was given a kick just as we were hauling him aboard. He had an awful wound in the back of his thigh and the guard caught him right in his wound – he passed out right away and we just managed to drag him in.

I found the Indian troops very selfish – they refused to share their water with us because of some religious fetish about needing it for toilet reasons. Consequently, the ten British soldiers were thoroughly brassed off by their attitude. After a stop-start journey of about sixteen hours we reached our destination Patras, in darkness. We staggered around and helped each other out of the train. We were under heavy guard and there were hordes of Italian soldiers lining the streets.