Summary of Harry Rock

“Why did I risk so much by attempting to escape. It was a challenge, and it kept me sane.”

H.J.Rock’s journey from capture and incarceration in an Italian POW camp to an escapee on the run from German and Italian soldiers is a testament to this man’s fortitude and resolve. Over the course of the Second World War, he is captured several times and makes multiple daring and incredible escapes. Roaming in the rural countryside, he relies on the locals’ generosity; travelling by the cover of night and resting through the day to evade detection.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital page 1]

Italy Escapes

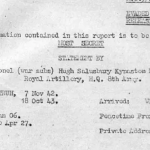

Henry (Harry) James Rock

April 1985

It is now 40 years since the cessation of hostilities in Europe – more generally referred to as the Second World War, and as my wife and my daughter have spent some time convincing me that it would be of historical, family interest for me to put a written record of my war time activities – particularly those covering the period of my detainment as a Prisoner of War in both Italian and German hands – this resume just gives limited details of the special events that took place from July 1942 to May 1945.

Although 40 years have passed, and consequently memory becomes more dim – it has only been possible for me to detail a rough outline of the events in this period. Nevertheless I hope that what I have written will be of some interest in years to come – particularly to my grandchildren.

From September 1939 until joining the 11th Commando Battalion of the Royal Marines I served in various capacities of the Royal Marines, spending some time afloat on H.M.S. Sussex. I also spent some time at the Naval Base in South Africa and later on, at Gibraltar and Malta – returning to England early in 1942. I was posted to Deal in Kent, which was then the reception area for new recruits, and I did a short spell as an Instructor at Deal. My next orders were that I was to sail to Egypt in charge of a unit of Marines. We sailed from Greenock on the S.S. “Louis Pasteur” to join the 11th Commando Battalion of the Royal Marines. After an uneventful journey around S. Africa we arrived at Port Taufiq from whence we were transported by lorry to join the 11th Battalion at Geneifa. The Officer commanding the 11th Battalion at that time, was Lieut-Colonel Unwin. When I arrived and handed over the replacement Marines I joined the 3″ Mortar Section and remained with this unit right throughout the time I was with the 11th Battalion. We trained in what was then Palestine and the Lebanon and Jordan The Mortar of that time was a cumbersome and difficult weapon to transport, and setting it up for firing could be seen today as humorous if not downright funny. We all mastered this monster of battle (i.e. artillery missile for firing bombs) so well that eventually we could pinpoint our target.

After additional training the Battalion was moved to Haifi, where we camped in the Oil Refinery by the harbour. From this camp we went in small units on submarines to carry out raids on Crete, and some of the other islands on which the Germans were using Radar equipment.

One of the raids in which I was involved in was on the tiny island of Kuphonisi off south-eastern Crete. Here the Germans had established a wireless station and the Royal Marines achieved complete surprise when they got ashore undetected and unopposed. The bulk of the force proceeded inland over rough-terrain. As they approached they were eventually spotted by an alert sentry and machine gun and rifle fire was encountered but we rushed the station and the defenders fled.

[Digital page 2]

We managed to destroy all the radio equipment and detonated all the enemy munitions. We also returned with a prize enemy porker we had captured – a PIG- OP WAR!

During our stay in Haifa we spent a lot of time training – practice landings from very unstable flat bottomed craft, which in later years would not have been entertained for any mission – especially of the kind we were to be involved in. We made several abortive practice landings in Famagusta, Cyprus. We trained in Jordan – this was primarily concerned with dune climbing and attacking in and out of valleys. These exercises brought my own mortar unit into constant use, as we had to give covering fire to all advance units. In theory these exercises were thought to be useful, but in actual practice they were of no avail as an exercise for landing from ships. After weeks of carrying out these landings and desert exercises orders were received to embark on the ships that were detailed to our destination. This was at the beginning of September 1942. I took my unit and embarked on H.M.S. “SIKH” a naval Destroyer, and on Saturday 12th September 1942 we set sail for Alexandria. We joined up with H.M.S. “ZULU” and 3 Motor Torpedo Boats who were carrying specialist engineers. On reaching Alexandria Intelligence Officers came aboard and gave us last minute details, small compasses, maps and special iron rations. We steamed out of Alexandria where we had a rendez-vous with 4 Hunt class destroyers and H.M.S. Coventry. On reaching the high seas we were told by the Battalion Commander that we were to carry out a raid on TOBRUK – CALLED “OPERATION AGREEMENT”. This raid was to be a diversification prior to the EL ALAMEIN advance.

Needless to say this news had different re-actions – some were quiet within their own thoughts – others were boisterous and keen to get into action – but all were frightened of the unknown – including myself.

This was the type of landing we had been training for and should he capable of doing well, and in spite of our fear we did have that unflinching faith in ourselves that we would be better than any opposition we might encounter.

The time seemed endless before our arrival off TOBRUK.

The attack was supposed to be co-ordinated with a land attack by the Long Range Desert Group, Our attack was to be made in two waves as there were not enough landing craft for everyone to go together. The landing craft (dumb lighters) were big open boats and were to be towed ashore by some that had motors. Air support on this raid had been promised and should have started to coincide with our arrival but one Sunderland Bomber hardly constituted air support, and only helped to convince the German and Italian forces that a sea landing was about to take place. The ensuing long range gun attack on our ships and boats only confirmed what everyone knew already – that we were expected.

I was in the second of two dumb lighters from H.M.S. “Sikh” being towed towards the harbour. I do not know how far we lay offshore but it seemed a long trip in these boats. Searchlights came on us – guns started firing firstly on us and

[Digital page 3]

then on to the “Sikh” and “Zulu”, In the heavy swell the tow rope of the lighter I was in broke away and with approximately 20 other Marines on the lighter we drifted on to the jagged, rocks. The boats were smashed up – but we managed to get ashore – at least a few of us. Some rocks were under water as well as on the beach and the water was deep and cold. According to the operation it should have been a plain sandy beach! We realised instantly that we had landed in the wrong place. We also realised that as we were ashore in the wrong spot and in view of the conditions and the enemy action we were doomed to failure. The landing craft being used were badly designed, badly made and totally unsuitable for the action we were engaged in. We were being shot at from several directions and enemy aircraft were in the sky. The beach itself was under fire – daylight was breaking and all hell had turned loose in and around Tobruk, and although we moved forward in twos and threes there was little we could do with the small arms in our possession that had been salvaged when the landing craft ran aground.

Many of the 11th, Battalion Royal Marines in the second phase did not get ashore. Many were drowned within minutes of leaving the Destroyers.

Back at sea the Sikh was illuminated – the heavy shore guns were more than the Destroyers “Sikh” and “Zulu” could cope with. The “Sikh” was burning and shells bursting all around. She was a destroyer not a battleship – very little steel lay between her highly sophisticated machinery and the enemy shells. She was soon in trouble. The “Zulu” tried to tow the “Sikh” far away but the tow rope broke and the “Zulu” was ordered to make headway and join H.M.S. “Coventry”, Eventually both the “Zulu” and the “Coventry” were sunk.

It has been documented that about 300 Royal Marines and 280 Naval personnel were casualties in OPERATION- AGREEMENT apart from personnel taken prisoners of war.

It has also been documented that OPERATION AGREEMENT – although not much publicity was ever given to it – was frustrated through no fault of the 11th Battalion having been landed in the wrong place. It was an attack that was doomed to failure through lack of good preparation, indifferent organisation and disgraceful security. As Lieut. Colonel Unwin remarked after he was captured as a prisoner of war on interrogation the Germans asked him “Why had his force arrived late!” The plans for the operation had already been in the hands of the Axis.

Getting back to my escapade – we scrambled over the rocks and had to make our own decisions as to what was best to do at the time. In the action that followed I suffered a wound in my neck, I remember vaguely holding a rag to my neck to stem the bleeding. I was losing a lot of blood and was eventually picked up by a German patrol and taken back to their base. My neck was attended to by an Italian Officer who claimed to be a Doctor! He said they were short of medical equipment and had to use a common knife to operate. He stitched my wound with a sewing needle – which has left a scar that I have still got today. After the usual spate of questions and evasive answers, I was told to prepare to

[Digital page 4]

move on to Bengazi to a special P.0.W. Camp. We were all loaded on to army trucks and started the journey to Bengazi, which turned out to be a hot and uncomfortable ride with the Italian Guards gloating. We all felt totally deflated and abandoned. On arrival at the Bengazi camp we were all issued with two small blankets and a canvas sheet for a tent. These were inadequate -as the days were hot and the nights bitterly cold. The sanitary arrangements in the camp consisted of various long trenches with long poles on stilts over which you placed your bottom, and all day long the poles were full of human bottoms; mainly because of the high level of dysentery in the camp. As the trenches filled we had to dig new ones. All the time getting closer to the tented area – which meant more disease and smells.

We were allowed – just one pint of water for cooking drinking and toilet use per day in a temperature of 110°F. Our food consisted of one soldier’s mug of rice per day and 20 grams of bread. Our hunger during this period can only be described by comparing ten thousand men with the same number of animals eating the grass around the wires of the camp. Medical attention in the camp was practically nil and in many cases men were left with nothing but a piece of canvas as a bed to die of acute dysentery. At one period these men were dying at the rate of 25 per day and were often buried without any form of coffin.

It was impossible to sleep in the two blankets given to us by the Italians. They were very small, and were practically walking with lice and vermin. Many men contracted various diseases of the skin through sleeping in these blankets.

During this period my neck started playing up and causing me a lot of pain, I was eventually moved to the hospital in Bengazi. This hospital was run by Huns and I received treatment to my neck.

From being taken capture I never met up with anyone from the 11th Battalion or anyone from the “Sikh”. I have heard – many years – afterwards – that the majority who were taken prisoners of war were taken to Bengazi. In March 1943 a unique exchange of British and Axis prisoners of war took place on the Turkish coast. Many of the prisoners captured during Operation Agreement were amongst this repatriation.

Hot for me – by this time I was in Italy!

Whilst I was in the hospital in Bengasi the British Army had started their advance from El Alamein and news had come through with instructions that all Prisoners of war were to be evacuated to Italy. At first we were informed by the Italian Commandant that all patients in the hospital would be left behind for release by the 8th Army because the Italians could not find enough transport to move us as veil as their own wounded on their retreat. However, luck was against us as early one morning in late November 1942 we

[Digital page 5]

were herded on to an Italian Hospital Ship which had called into Benghazi . We were transported to Bari in S. Italy. In Bari we were transferred from the ship to a hospital which was again run by Nuns.

On this occasion I received, as did everyone else some better treatment and the wound in my neck soon healed. Whilst I was in the hospital in Bari I became quite friendly with a member of the South African Forces, who at the time was very ill with a serious leg wound. One of the Nuns who was English speaking, told me that Ian Cameron would need an early blood transfusion, otherwise he would die. My blood group matched with his so I agreed to be the donor. Arrangements for the transfusion were made and as a result Ian is still alive today and we still, after all this time, communicate each Christmas, I have never seen him since that time.

When I had recovered from my neck wound etc., I was sent to a camp in N. Italy, transported by cattle truck for onward movement to Germany. This camp was known as Camp 45 and when I arrived I met up with some old friends from Bengasi – but no one from the 11th Battalion or the “Sikh”, Amongst the prisoners at Camp 45 was a member of the Fleet Air Arm – whose name was Jack Fallon, and in the intervening weeks Jack and I became very friendly – to the extent that we shared most things within the camp i.e. food rations etc. Most of our time was spent planning an early escape and we finally got away from this camp by simply walking out with the working party – and not going back.

We headed due South living principally on fruit and stolen vegetables, and we had to move at night, for obvious reasons – and hide during the day – mainly because there was at the time a considerable movement of troops from Worth to South. Jack Fallon and I reached a spot near ASSISI in the Grand Sasso mountain range, when we were challenged by a German patrol and retaken as prisoners.

We were sent to join other prisoners at PERUGIA to await despatch to Germany -once more.

We were loaded into cattle trucks and sent on our way to Milan. En route Jack and I started cutting away the floor boards on the cattle truck and we had almost succeeded in doing so when the train pulled into MILAN station. The intention was to create a hole big enough to enable us to drop down in between the lines, when the train slowed down.

We were all off loaded and paraded at MILAN Station whilst a search of the train was made. When the floor cutting was discovered, all the occupants of that particular truck were lined up and we were told we would be SHOT! It was a very frightening moment.

We were saved by the intervention of a more lenient German officer, who ordered us to be searched and all knives and other cutting implements were confiscated. We carried on our journey towards Germany, and on arrival at a small wayside station on the German side of the Brenner Pass we were all offloaded on to a siding. Jack noticed a train immediately opposite which would have appeared to have been an Arms Train going South, and as at the time the Guard had moved away from us

[Digital page 6]

we were able to slide down the siding and get underneath the armoured train, which left soon afterwards and took us non-stop back through the Brenner Pass to Italy. We got dropped off this train at a small town called BOLZANO, and laid low in the undergrowth until dark, when we once more started our march Southwards towards VERONA.

During this period in the PO valley we lived entirely off the land mainly from fruit e.g. oranges.

It was about this time that the British had started their first landing on Sicily.

After many days we reached a point South of CESENA, which was near the coast. Our intention at the time was to keep as close to the hills as possible between FLORENCE and RIMINI, and we were helped very much during this period by the Italian women who supplied us with some food and advised us where the SAFE houses were – for shelter.

After what seemed almost a lifetime, we reached the River Sangro and met up with two other escaped prisoners of war. These two had escaped from a camp near RIMINI, and like us were heading South hoping to join up with our Forces. A long way to go – but worth the effort, as we had already come a long way. We had come through pretty rough terrain existing on anything we could find to eat along the way – our diet at this time was mainly peas. In acquiring food we had some very narrow escapes from unfriendly Italians. Once or twice from German troops on the move South, but in every instance we managed to get away into the hills.

After a few days with the two P.O.W. we had met up with we all decided that four was too great a number and were more likely to be picked up – so Jack and I bid the other two farewell and carried on by ourselves. We crossed the River Sangro and were heading inland towards the Grand Sasso mountains hoping to use the mountain range as a guide. The weather was getting much colder as we got higher into the hills, and as there was no available food we had reached a hunger stage of sheer desperation. The only animal we could find was a wild cat, which we managed to kill and in a small ravine we made a fire and cooked the cat meat and pure hunger made the meat absolutely delicious and was helped down by our own imagination.

As usual we had to rest during the day and move at night, and we thought we were doing well, but we got over confident and careless and were surrounded one day by a German Mountain patrol. We insisted that we were Italian hunters, and we were taken by the German patrol to work as labourers on Gun emplacements they were building into the hills. We were doing quite well until one day the two ex-prisoners of war that we had parted from earlier were also brought on to the Gun site and seeing us they immediately spoke in English – not realising that we were posing as Italians. Immediately we were

[Digital page 7]

taken into custody by the Germans, and taken to their main camp at POPOLI where we were once again put through the usual interrogation – and the four of us were once again put on a truck and taken to CHIETI where there was an established Prisoner of War camp.

On arrival we discovered newly captured officers and other ranks from the Green Jackets who had been captured in South Italy, who were all still in a state of shock and unbelief at finding themselves behind barbed wire with heavily armed German Guards all around them. Into this atmosphere of doubt and uncertainty we were bundled, but it was wonderful to get some late news from home, after spending so long in the hills. We soon made some new friends and settled down to regain some of our lost energy and desire to be out again. During this period in CHIEH I became friendly with a British civilian in officer uniform who confided in me that he had, in fact, been working behind the lines in Italy as an agent for the British To safeguard himself he had to pretend that he was a serving officer in the British forces. He enlisted help to get him out of the camp. He joined our Escape Party – and as far as I know this man was successful in getting away, out I have never heard anything of him since.

The Escape Party was formed with some of the longer termed prisoners and many were interested. One of the people involved was a man called Len Cooper, with whom I was to form a long ‘on the run’ friendship.

in the kitchen of the camp we discovered the beginning of a tunnel that had been started by some previous occupants of the camp, and after deciding that we should continue the tunnel we got ourselves organised into sections to complete the work on the tunnel, which we hoped would lead to freedom.

I was parted from Jack Fallon in this venture, as lots were drawn for sections, and I was drawn to join Len Cooper’s section for work on the tunnel. As the Germans only did a morning roll call we were able to remain locked in the kitchen and work through the night. The operation was carried out by all four people in the section moving into the tunnel and the leading one taking forward with him a wooden box that was attached to a long string. Each time the box waw filled he tugged on the string and the full box was hauled back to the kitchen, where it was emptied into the kitchen garbage bins. When the leading man had completed his period of digging, he came back and number 2 man took over the digging. The garbage bins were emptied by Prisoners of War each day at a nearby tip. The driver of the truck was an Italian. When each section had completed its night work they returned to their huts each morning in time for early morning roll call, and they hopefully slept during most of that day. Working flat out in this way the tunnel was completed in about two full working weeks, and the smallest man from the Section on final duty was sent along the tunnel to report on the position of the exit. This man, who in the event did not take part in the escape, reported that the exit was partly screened by woodland: which was later

[Digital page 8]

proved to be totally incorrect. The opening was, in fact, some yards short of the woodland, and was overlooked by two German Sentry Boxes.

Len Cooper and I were drawn number 6 and 7 going into the tunnel, and half way along it was necessary to turn on our backs to crawl underneath a sewerage pipe that cut straight across the tunnel.

This was the most difficult part of manoeuvring inside the tunnel, as it was completely dark and any mistake could have resulted in catastrophe for all concerned When Len and I got to the tunnel exit it was in fact to find that it was some yards short of the surrounding woodland, and was overlooked by the Camp Perimeter Sentry Boxes. This fact obviously created a danger hazard, but as we had gone so far there could be no turning back at this stage.

Each one on reaching the exit had to move very quickly into the protection of the wooded screen, some yards away. This was an operation I would not ever want to repeat; as all the time we were expecting the German Sentries to start firing their machine guns in our direction. Needless to say, because of this, we were all in a state of some fear and trepidation. As far as I am aware all the people taking part, that night, got away successfully.

Len Cooper and 1 joined up in the woods and after a hasty discussion decided to head North West to enable us to get away from the other escaped prisoners of war, all of whom we imagined would be heading due South. At this stage it was very important that we all should split up into groups of 2 or 3, as this was the most likely way to avoid recapture.

Before continuing my story I would just like to mention, at this stage, none of the newly captured prisoners of war took part in this particular escape, and I did not see Jack Fallon again until the war was over, and then only for a short while in Hull, Yorkshire. He had changed considerably in the intervening period, as no doubt we all had, but the war had had a very bad effect on his nerves. He was in the Forestry Commission – and I have not seen him since that meeting in 1949.

The night of the escape from CESITI was frosty and there had been a pretty heavy fall of snow, which all helped to make our movement pretty difficult. On top of all this the clay of the tunnel started drying white on our clothing, and in the moonlight we were becoming quite visible. He were forced to lay up for a while in some bushes where we endeavoured to rub off the drying mud from, our clothing.

Len and I followed the river PESCARA for some hours, mainly to get a bearing, and at one stage we were very lucky to notice some German Sentries on what was obviously a small supply bridge, – so we had to lay low again until dark and then wait for the Sentries to move over to the opposite side of the bridge. When they had done this we crawled across the road into cover on the other side. We Were -very lucky because obviously the Germans did not expect anyone to be in the area at that time. We continued to use the river as a guide, in spite

[Digital page 9]

of having to cover greater distances, following the flow of the river, but the primary object at that time was to put as much distance as possible between ourselves and Chieti. We did this for a few days and nights and then decided to turn South away from the river towards the hills at Scanno. Once again hoping to cross the River Sangro further South. Travelling was becoming evermore difficult because of the dry snow building up on our footwear. One minute we would be walking 8ft. fall and the next minute the snow would collapse and we would be walking and collapse down to earth with a bump.

At this stage we were wearing army clothing – army boots and big jumpers which had been supplied from the clothing stock at the camp.

We were both very- tired at this stage and we made up our minds to search out a suitable isolated peasant farmhouse – for food and possible rest. We eventually found one and we agreed that Len should approach on one side and myself on another. As we got nearer we both saw the German horses so we got away from there, as quickly as possible. Fortunately we were not seen. We continued to move on deeper into the hills, and eventually came across a very lonely farmhouse, where we could find no trace of enemy occupation, and everything appeared to be quire safe. We made some noise – at some distance from the house – and waited for movement – giving ourselves the chance of getting away, if we were not given a friendly greeting. As was usual on these occasions, the door was opened by the woman of the house, and from a distance we made ourselves known as English escapees. She could not understand English but in our own brand of Italian – which we had picked up along the way – we made known what we wanted. She seemed to understand enough to invite us in to meet all the family. After making our normal cautious approach we were met with utter excitement and pleasure and very quickly we were provided with some food, and our wet outer clothing was taken and dried for us. Many of these peasant families were anti-German. We were then taken to the barn -which at that time in most of these peasant farms was immediately underneath the main house. Straw beds were made up for us in the cow mangers, where we spent our first night for quite some time – in beds of straw with cows breathing on us from above.

This was really an amazing experience and one that will live with me always of sleeping in a manger.

The following day Len and I came to an arrangement with the family – where we exchanged our Army clothing for some civilian garments that would be safer for us to wear – and would make us less obvious. The family insisted that we stayed until. they could gather some information for us as to where the Germans intended setting up a Defence line in the area.

One of the favourite meals provided by the peasant farmer families was a dish called Palente. The preparation for this dish was as follows:

The kitchen table of plain wood was completely scrubbed and a great pot of water

put on a charcoal fire into which – when it reached boiling point – was put a great mixture of yellow meal flour.

[Digital page 10]

It became a great stodgy mixture. On a separate charcoal burner would be a little saucepan containing tomato puree, and when the stodgy meal substance was ready, this was literally poured on to the centre of the table and spread all over it. The pot of tomato puree was then spread all over the meal mixture, and on top of the tomato puree the woman of the house would sprinkle minute pieces of meat – very, very sparingly. We were then each given a fork and told to start eating directly from the table. In our case we tended to make a bee-line for the nearest piece of meat but were promptly told to eat from the outside inwards. Believe me when you are hungry this meal was absolutely delicious. The British name for this dish was -THE MAP OP ITALY!

One day a lone horseman appeared at the house, and as there was no way Len or I could have moved on without endangering the family we decided to use bluff. When the German horseman arrived at the gate, I went towards him and asked in my ‘best’ Italian what he wanted. Fortunately his Italian was worse than mine and he just indicated to me to hold his horse – which I did. He went to the house – and all he was looking for was food. He took chickens and eggs – which the family had to give him. He came back to where I was standing holding his horse and when I had helped him to remount he presented me with a cigar for holding it for him – and he went on his way. This situation could have been quite dangerous for the peasant people. Following this incident Len and I decided to move on, as the house would now be listed by the Germans as good for food. Any future visits by them might very well be disastrous for us and the family. We packed up our few bits and pieces and bade farewell to the kindly family. We set off to the hills once more on our long journey South.

We were still heading towards Scanno. We moved more into the hills again resting by day and moving by night. During one of our rest days we overhead English voices in the distance and we thought we should investigate. We discovered a small group of prisoners of war being guided by an Italian civilian – who said he would guide them to the front line. We agreed to join them. They had made a huge resting place in a hole in the mountain side, and were waiting for supplies of food which were supposed to be dropped by parachute. This was quite genuine but was all new to Len Cooper and myself, as we were totally unaware that any such arrangement had been made.

We stayed with these fellows for a few days and sure enough an aircraft did arrive and dropped supplies of clothing and food by parachute, but as these were of considerable distance away from where we were – most of the food and clothing was stolen by the Italians before we could get to them. In the event – this operation proved our downfall – as a German patrol had seen the drop and the following day we were surrounded by armed Germans and taken to their local headquarters at SUIMOEA, where once more we were questioned and sent on to a detention centre at L’ACQUILA. As far as I can remember this would be approximately in January 1944.

[Digital page 11]

The arrangement for these hampers of food and clothing to be dropped in the area as supplementary supplies to the prisoners of war, who were at that time congregating with a view to being escorted through the front line by an Italian Guide was instituted by the British Military authorities.

Since getting out of Chieti Camp, Len and I had been befriended by many Italian peasants, so it was a bitter blow to us to have been retaken once again. The detention centre at-‘ACQUILA was an old hospital that had been turned into more of a military barracks, and we were detained in a ground floor section at the rear of the building in one big room. We slept in wooden bunk type beds -four men to each bed unit. Len and I got together some of the other occupants and we started, once again the painful process of creating a tunnel. This was done by moving a bed section and excavating below it. The earth removed was placed in rubbish bins and was carried out each day by Italian workers and tipped into a pit over a small wall opposite our building. As this was a German Army Headquarters, Italian women were brought in each day as cleaners for the area occupied oy German officers. One day one of the prisoners of war after getting hold of some clothing, dressed as a woman – and walked out with the Italian women cleaners – and to the best of my knowledge this fellow got away. We continued our tunnel for some days, and we were making relatively good progress until one morning we were surprised when the German Commandant ordered us all out for a special roll call. We were all paraded in the yard outside for him to carry out an internal inspection, it was perfectly obvious that someone had informed the Germans about our tunnel and it was found and blocked up. We were all subjected to -pretty hard punishment – i.e. multiple roll calls in the middle of the night and very reduced food rations.

Following this we were all given a questionnaire to complete. One of the questions on this form was “What was your occupation at home”? Every single one in our room answered this question by putting – coal miner – tin miner – or London underground worker! This infuriated the German Commandant, who had us all paraded before him – when he gave us all a really good dressing down in English – which he spoke quite fluently – and further punishment.

We accepted all this as we all realised that the Germans had no sense of humour anyway.

Shortly after this we were told to pack up and we were loaded on to vehicles and taken North to a camp near Florence, which had been an Italian Military Camp. It was consequently ideal as a prisoner of war camp. We met up again with some of the men who had been at Chieti with us, and we were brought up to date with news from the various front lines. It cheered us up and also increased our determination to get out again. Within a week Len and I had discovered an entrance to a sewerage pipe that we thought might help us to get away. Me set about collecting as much information as possible of the direction of the sewer and its possible exit.

[Digital page 12]

When we were satisfied that we had collected all the information that might be available we informed the British Camp Commandant about our intention, and we were given the O.K. to proceed. We got into the sewer entrance after the evening roll call and started our crawl towards the opening, which we estimated was about 30 yards from the camp perimeter. The stench in the tunnel was overpowering and at one time we almost turned back. We forced ourselves to carry on, and finally reached the exit opening and by this time we were covered in slime. Unfortunately our freedom after all this effort was short-lived – and we were captured and taken back to the camp.

In retrospect we were both quite pleased as we had reached the stage when we could not stand the filth and smell any longer. In fact the smell lived with us for weeks afterwards.

This was to be our last attempt to escape as we had had enough. We were getting rather weak. We settled down to camp routine and we were all moved by Cattle Truck to Moosburg, near Munich. This was an enormous camp holding literally thousands of prisoners of war of all nationalities. This camp was called STALAG 7A. Len and I were put in a special compound because of what we had been doing, and we were sentenced to 14 days in solitary confinement – where we had no contact at all with anyone. Our only meal was a bowl of Skilly daily and one container of water. When we were released from solitary confinement we were put in a compound full of American Air Crew, and at the request of the Americans themselves, we took charge of the compound of 500 men.

We were responsible for food distribution and red cross parcels, whenever these became available. Len and I were also responsible for the cleanliness of the men in our charge and also the huts themselves, but with the American state of mind this was sometimes very difficult as they found it extremely hard to accept the numerous deprivations forced on us by the Germans.

The huts were divided into units of 150 people and in each unit the sleeping arrangements took the form of large bunk beds, accommodating 12 men in three tiers. Each tier was made into 4 individual beds alongside each other. Each bunk bed group of 12 men was formed into a section who selected their own section leader, who was responsible for getting his section out on parade for roll calls, every morning and evening and at any other time requested by the Germans.

Rations were dictated very much by the availability of food in the main kitchen, and on odd days if we saw an old horse being led into camp kitchens, we knew we would be getting some meat in out skilly ration the following day.

The only other variation from the routine food supply would be the arrival of RED CROSS parcels. In the early days of the camp, parcels were issued on the basis of one parcel per two men. In the later stages of our prisoner of war life parcels were only issued one parcel per eight men. Most of the prisoners formed themselves into small groups of 2, 4 or 6 and in this way were able to share their food supply and make things last much longer.

[Digital page 13]

Each of these groups made their own blower type fires out of tins and used little bits of wood found around the camp – to manufacture charcoal for these little fires, and in this way were able to make hot coffee and cook small meals for themselves from the contents of the RED CROSS parcels. It was usual for the prisoners go barter with the German Guards usually using cigarettes (from the parcel) as money, in exchange for German brown bread and eggs. This was a very useful way to supplement our meagre food rations.

One of the questionable ruses used by the prisoners was to replace used tea leaves (from our parcels) in the original packet and sell the packet to the Germans for whatever could be obtained. We had been doing this quite successfully for some time, until we were approaching Christmas 1944 when we needed some flour to make what we fully believed would be our last Christmas pudding as prisoners of war. We produced a packet of dried used tea leaves and arranged with the German Guard to exchange the tea for flour, which he agreed to do. The following day he brought us a packet of flour. We were highly delighted and starred mixing the dried fruit we had received and saved up from our Red Cross parcels – all kept specially for our Christmas pudding. We mixed in with the fruit the flour we had bought, a couple of eggs bought from the Germans with cigarettes, some dried milk and added water. The mix got harder and harder until it finally set like concrete. The German Guard had obviously caught on to the dried tea leaves and had supplied us with plaster of paris instead of flour. This meant goodbye to our hopes of a Christmas pudding, and we had no option but to accept it all in good grace.

During the final 6 months we were in Moosburg multiple bombing raids were being carried out on Munich. The United States Airforce by day and the Royal Air Force by night, and principally because of these large scale raids on Munich the German-Army in command of the camp dropped all pretence of accepting the Geneva Conventions as appertaining to prisoners of war. As so much damage was being done to the city of Munich and surrounding area the German Commandant insisted that all prisoners irrespective of rank would have to participate in carrying out work in the city. The most important work required to be done was the repair of the railway lines in and out of Munich as this was a highly important junction for supplies to the whole area. The one concession the Germans did make for the protection of the working prisoners of war was the election of responsible people as Red Cross representatives. I was one of the people elected by them to wear a Red Cross arm band and I was responsible for the welfare and humanitarian treatment for the prisoners working on the railway lines. I think I was elected for this job because I flatly refused to carry out any manual work of any sort for the Germans. All this work was extremely hard and of long duration particularly for men who were underfed and without proper warm clothing. The Germans were not in any way concerned with the welfare of the prisoners in this regard – their principal pre-occupation was to get the railways working – and how many men died doing this week was quite immaterial to them.

[Digital page 14]

The Russian prisoners of war in the camp were treated like animals as they were not protected by the Geneva Conventions, and on some occasions we actually witnessed Russian prisoners being shot for being too close to the perimeter fence.

All the Russians were herded out every morning to work and it was a pitiful sight to see these men almost dragging themselves to the cattle truck. We knew that far fewer returned to the camp then left in the morning. One could only assume that they died whilst working through lack of nourishment.

Although we were all weak through lack of proper feeding we were never quite as bad as the Russian prisoners because we were able to supplement small German rations with the occasional contents of a Red Cross parcel.

During one of these working periods at Munich station one of the working groups was made up of Canadians, who were instructed to move out damaged rail sections and replace them with new ones. These Canadians were difficult people to handle and the German Guards could not understand them. One of the things they indulged in to the great consternation of the Germans was to bend down to lift a long section of rail and straighten up again – leaving the rail on the ground. The excuse they made was that it was too heavy and needed some more men. Even when more men were added they did exactly the same thing again, and the German Sentries were beginning to get really angry. In the end the Germans told me that if they did not move the rail they would all be shot.

I felt at this late stage in the war, when they had nothing more to lose – the Germans might very well carry out the threat to shoot I advised the Canadians to move the Sections but drop them in the wrong places. In this way they would be carrying out what was expected of them, hut at the same time delaying the repairs to the line. They accepted this advice and caused more confusion by moving sections of line to areas where they could not possibly be needed. The net result of their contribution was that they were never sent out to work again, and were put on bare rations.

During this period the German Command at the Camp was beginning to alter its attitude towards the prisoners, and more movement was being allowed within the camp area than had been previously. This enabled Len Cooper and myself to get a pass to visit some other compounds of the camp.

It was important at this late stage in the war that all the Compound Leaders could prepare a plan of campaign in the event of a possible evacuation of the Germans. If the Germans did evacuate the camp it would be absolutely important to prepare some form of command within the camp structure to protect ourselves. In April 1945 we were advised by the German Commandant to stay well within the camp confines, as an attack was expected and we might be in some danger.

The American attack took place on a Sunday morning, and in spite of the warning we were all out to listen to the Guns and whistling shells going over the camp. The whole action surrounding the camp only lasted a few hours, and by the Sunday

[Digital page 15]

afternoon the area and the camp itself was in the hands of the American Forces, commanded by General PATTON.

On the following day – with cheer after cheer from the prisoners of war General PATTON walked through the camp – saying hello to all and sundry.

All the Germans had quickly evacuated the camp an hour or so before the arrival of the Americans., General Patton was a very outgoing character and walked through the camp with his two white handled pistols hanging each side. He informed each compound as he passed, that he would have us home as quickly as possible, but that we must remain in the camp, and we would now be taking orders from an American Commandant.

When a search of the camp was made numerous Red Cross parcels were found in a German store. These had not been distributed to the camp prisoners of war, and were obviously being retained to feed the German soldiers. They themselves at this stage were very short of food and other supplies.

During the last 6 months in the camp it was almost a daily ritual for a lot of hungry prisoners to be seen around the grassy areas of the camp perimeter rooting out the thicker white roots of the grass to add to whatever meagre food might be served up that day – which made the finding of the Red Cross parcels -which had not been distributed even more tragic.

In fact, it was reported to us that the main German defence in the area was carried out by collaborating French soldiers in German uniform. During the early period in the Prison Camp the camp was controlled by members of the German S.S. who were completely brutal and inhumane, particularly in their attitude to the Russians, and it was not unusual to see them shooting a Russian prisoner of war for just being too near the trip wire near the camp.

Later in the war the S.S. personnel were relieved by older members of the Wehrmacht who were not suitable for use in the front line. These men took a completely different view and their conduct was much more humane.

Quite apart from the French military collaborators great attempts were made by the Germans, using people like William Joyce and John Amery to go around the camps attempting to persuade British and American prisoners of war to join the British Free Corps to fight against the Russians.

I think they may have been successful in getting a few people to join this Corps, but if they were it was a very small percentage of the total number held in prisoner of war camps.

In the main their efforts were completely despised and jeered at by the majority of prisoners of war.

As is generally known, William Joyce (Lord Haw Haw) was sentenced to death and was hanged at Wandsworth Prison. John Amery was sentenced to death but was reprieved and served life imprisonment.

Within a couple of weeks General. Patton’s li as on staff had made arrangements for us to be flown to our respective destinations and as Len Cooper and I were in an

[Digital page 16]

We were taken by motor transport to a nearby United States Air Base and flown in groups to Brussels in a Dakota aircraft of the United States Airforce.

When we arrived in Brussels we were segregated from our American friends and handed over to the British reception centre where we were deloused, given a bath – a haircut and issued with new clothing and sufficient money to cover our overnight stay in Brussels.

We were not allowed to leave the reception centre until we had been de-briefed. The following day we were taken to Brussels airport where we boarded a Lancaster Bomber of the Royal Air Force, and flown to an air base near Oxford. Here, we received a wonderful greeting by members of the Royal Air Force as it was V.E. Day.

We were given food and gifts of cigarettes etc. After the reception which was held in a huge hanger, which was used to receive all prisoners of war returning from Germany we were advised to stand by for transport to take us to our own home establishment. As I was the only naval person in this contingent I had a 32 seater coach all to myself to take me all the way to Portsmouth to the Royal Marine Barracks – where I was re-united with some other prisoners of war who had returned earlier.

Once again we went through the usual de briefing and medical checks, and on being passed O.K. we were given leave for an unlimited period.

This is my story of capture, escapes and recaptures and prisoner of war life.

I am sure there are many with similar experiences. The events described did much to create in me a better understanding of my fellow men. I often ask myself now – WHY did I risk so much by attempting to escape. It was a challenge and it kept me sane.

Appendix.

In September 1990 I was invited to attend an organised Reunion in Portsmouth of the surviving naval personnel of H.M.S. ‘Sikh’ and the surviving members of the 11th Batt. R. Marines. Only 50 naval survivors and 7 R. Marine survivors were able to attend the Reunion. One of the people I had the pleasure of renewing acquaintanceship with was an naval coxswain of the lighter that towed our dumb lighter into Tobruk.

H.J .Rock