Summary

Virginia Nathan, a Jewish refugee, and George McHattie, an escaped British Prisoner of War, travelled back to the Avezzano area forty years after they escaped from the German army in 1943. Nathan recounts their separate stories before they met and after. McHattie was accompanied by POWs, Gordon Clover and Mike Williams, before they were separated by the Germans forces, however McHattie managed to escape again and make it back to Allied lines.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[digital page 1]

(Handwritten note in Keith Killby’s writing:) Story of their reunion meeting after 40 years and his ‘interview about his vicissitudes with two other POW (Prisoners of War) in the Avezzano area.

[digital page 2]

London, 24th January 1999

Dear Mr Gordon Lett,

I have been given your list of stories regarding the POWs in Italy. I am sending you a short story which might interest you about an English escaped prisoner who I met during the war and found again after forty years. I was escaping from the Germans being of a Jewish family living in Rome at the time. I shall include some details with the story so that you may understand more about me and George MacHattie who I met up in the Abruzzo mountains in 1943. He is now in Australia and we correspond frequently with each other having become good friends. I live in Wimbledon in an old pensioners bed-sit flat.

I have just published in Italy a book about our adventurous story when we escaped to Forme near Avezzano. I wrote this story when after forty years George MacHattie came to stay with me in Italy in order to go and revisit the places where he had escaped and met us.

I am not a qualified writer but a “story-teller”, self made one. If you can read Italian I will send you my book which I am hoping to have published over here in English.

Please excuse my way of writing since I am not used to sending official letters and also I have just learnt to use a computer!…

It would be nice for George MacHattie to know that his story is in the hands of people that can appreciate it.

Hoping to hear from you.

Sincerely yours,

Virginia Nathan

(digital page 3)

We Came to Forme

by Virginia Nathan

With the collaboration of George McHattie

(digital page 4)

We Came to Forme

It was a hot humid day, and the sun filtered through a hazy sky. I was on my way to the Fiumicino airport near Rome. I was excited for after forty years I was going to meet someone that I had met in the Abruzzi, when way back in 1943 we had both been escapees from the Germans. He was at that time a young prisoner of war who had escaped from a concentration camp at Bologna. I was a young girl who had escaped with my family to a small isolated village called Forme, way up in the mountains near Avezzano. I couldn’t help thinking about the strange way we had after so many years, come across one another.

All I knew was that George, the young prisoner, had escaped finally and reached the allies. I had also survived after many incredible adventures.

I hadn’t really thought much about the three young handsome English prisoners that we had met up there and with whom we used to make tea and sit and chat. But one day my father was visited by someone who produced a photo of three young English escaped prisoners asking him if by chance he had come across them. My father had been very surprised and had told the man that yes, he had seen them and had told him the little we knew about them. So I was very happy when father handed me the photo with the address of each one. This same photo I still have with me in my photo album. The album had been kept with great care throughout the forty years and I never thought for a moment that it would lead eventually to the strange events that took place.

I had been interviewed three years back by a very well-known author about our experiences during the German occupation of Rome. I had related the whole story to him and he had then mentioned some of our experiences in a book which he later published. I hadn’t thought about this episode any more, until a year later, when I decided to write the story of our escape. It was then that remembering our meeting on the hill-top with the English escaped prisoners that I pulled out the photo of George and his companions. I then thought that I would like to have the photo put in the book if it ever got published. I decided that I would write to one of the old addresses I still had of the boys. I wrote to George but the letter came back with “address unknown” on it. I gave up and decided to leave it until something eventuated.

Meanwhile, George who is living in Perth, Australia, had picked up the same book at the local library and had recognised my name in the book. He had immediately written to the author, Raleigh Trevelyan asking him for my address. The author did not have my address for I had meantime left for Italy and was living in the country near Rome.

(digital page 5, original page 2)

However, he had my sister’s address in London and gave that to George who then wrote to her. One day I received a very excited phone call from my sister, telling me that she had just got a letter from George McHattie and gave me his address. I couldn’t believe it – it seemed so strange, such a coincidence. What strange power had made it possible for both of us after so many years to recapture those frightening days spent in the village of Forme. I wrote to him immediately and we exchanged letters for almost a year. Then I received a letter from him saying that he was coming over to Italy and afterwards to London. I wrote back telling him to come and stay with me, for I did so much want to know more about what had happened after we had both gone our separate ways, both escaping in different directions from the Germans.

Now here I was, driving into Fiumicino Airport to meet George. I wondered how we would recognise each other, for almost half a century must have made a big difference to both our appearances. I felt slightly uneasy for I could still recollect more or less what I looked like in those distant days. Now I was an ageing woman in her sixties with grey hair and many wrinkles. I had not given him any form of identification, neither had he, I tried to think what he would look like, I could only remember a handsome tall fair haired young man with a charming smile. I knew he hadn’t lost his sense of humour by his letters, I had not lost mine, thank God, but I had lost many other things… All I hoped was that I would recognise him and that seeing me would not be too much of a shock.

I entered the busy airport arrival hall and stood among the crowd of people waiting for the different flights to arrive. It was packed with all kinds of different groups; Americans, Indians, Italians, some of whom were holding out placards and stretching their necks to see the many people coming through the customs area, pushing their luggage as they in return looked out anxiously to see if their friends or dear ones were there waiting for them.

I didn’t have a clue as to George’s appearance, but I also stretched my neck to see if there was any lone gentleman walking through, I saw various single men coming out and looking around. One of them was a big fat man with a beard and with dark fierce eyes, I thought for a moment, could he have changed that much? Then another rather thin tall chap seemed to be looking for someone, so I walked around him ready to grab any sign of recollection. He Just seemed to stare right through me, till he suddenly waved his hand at someone corning in through the main entrance. I started looking again at all the other passengers coming through the gates and then I saw him. It was immediate, and of course I felt that I would have recognised him among any crowd. Although his hair had thinned, his cheery

(digital page 6, original page 3)

face and laughing eyes had not changed in the least, and he still had a tall upright figure. He also had little trouble in recognising me. We warmly embraced and left the hot packed hall for the car.

It was a very pleasant drive back to the Stalle – the house in which I was living with my five cats and five dogs. The old red building stood on top of the hill surrounded by olive trees, and in the distance, the tall cypresses of Hadrian’s Villa outlined the horizon with the majestic wall of the Philosophers, and the many cubicles underneath where the slaves once lived.

It was later that day when we sat quietly outside in the pleasant evening breeze sipping a refreshing drink, that George started to tell me his story.

First of all, I asked him “How did you reach Forme and from where?” and then “what really happened when you left us that day?. I want to know the whole story from the start”. George smiled, “It’s a long story and you must tell me yours later, so here we go”.

“I was with the Eighth Army in North Africa and we were retreating towards El Alamein to regroup and try to withstand Rommel’s advance to Cairo. I was ordered to drive at the rear of my column and report any enemy movements. However, my truck with a wireless signaller and driver, broke down somewhere in the middle of the desert and as we were trying to get it going, a German patrol of armoured cars came up and surrounded us. We had no choice but to surrender or we wouldn’t have lived to tell the tale.

The Germans took us to their camp and later handed us over to the Italians who brought us back through Tobruk and Derna to Bengazi. After some time there, we were shipped over to Taranto, and from there to a POW camp in Bari. We spent some weeks in Bari and then were split up into various camps in Italy, I went to a camp at Sulmona and spent the next ten months there.”

“All those months, how were you treated?” I asked.

“The treatment was quite good really and the camp was well organised as far as food was concerned. We didn’t eat very much but what we ate was well cooked. We had a very good Australian messing officer who had good contacts with the Italians and was able to buy plenty of fresh fruit and vegetables which helped out with the meagre rations and also making the canned food in the Red Cross parcels more interesting. At Christmas time in 1942, we were able to get plenty of supplies of food and drink because we ordered far more than we expected to get, but surprisingly the Italian commandant granted us everything we asked for.

(digital page 7, original page 4)

So at Christmas time we had several very good parties and ate and drank far too much”. George laughed heartily and carried on with his story.

“However this didn’t last and as the cold winter weather set in, and snow covered the ground outside the camp and carpeted the surrounding mountains, we became hungry again. The cold winter changed gradually into spring and then into early summer, and this helped to make us less concerned about food. Then we heard the news on the radio that the Allies had landed in Sicily, and there was great hope that soon they would cross to the Italian mainland and reach our camp. However, this was not to be, for we were moved further north to another camp in Bologna. It was there on the eighth of September 1943 that we heard the news that Badoglio had supplanted Mussolini and made an armistice with the Allies. The Italian commandant withdrew his guards from the gates of the camp and we could have walked out at that point. However, the British Senior Officer advised us not to leave the camp as it would only create havoc in the surrounding countryside and alert the Germans, But the Germans did not need to be alerted because in the middle of the night they surrounded the camp with an infantry battalion and chased those people who managed to flee through the gates, back into the camp, shooting one of my friends who later died in hospital. The Germans kept the camp well guarded and a few days later took us in lorries to the railway station at Modena where we were put into cattle trucks that were presumably destined to take us to Germany. When it became dark, I watched the German guard, waiting for him to almost reach the end of his beat, then I slipped from the wagon and hid in a pile of rubbish which was beside the railway track. I had to stay there all that night and all the next day as the train did not leave until the following evening. It was very hot and uncomfortable in this hidey-hole but I managed to stick it out as I would not have had a kind reception from the Germans had I emerged from that place. When the train left, I waited till darkness, and then, brushing all the filth from my clothes, I came out from my hiding place”.

“Do you mean you were all alone?” I asked “and what clothes were you wearing?”. “Yes I was all alone and I was wearing a khaki shirt and trousers. I left the railway and went towards the city of Modena, having no idea where I should head for. As it was dark and as I presumed there was a curfew, I thought it too dangerous to venture into the city, so I found a deserted building in which I lay down and tried to sleep until daylight. At dawn, I walked into the city and up one of the main streets.

(digital page 8, original page 5)

I walked towards a group of Italian workmen on bicycles who were presumably going to work. One of them must have recognised me as an escaped prisoner for he rode up to me and thrust a loaf of bread into my hand, pointed to a side street leading off the main street and said ‘Go to the mountains’. I followed his instructions and diverged into the street that he indicated. Up the street I saw an old couple beside the door of their house. I felt that I was too conspicuous in what I was wearing, so I asked them if they could change my uniform for civilian clothes. They were very frightened, but they took me inside their house and gave me an old shirt, an old pair of trousers and jacket and a scarf, taking my khaki clothes in return. There were two carabinieri patrolling the street, so we waited until they had gone and then I proceeded up the street and eventually came into open country. The road passed alongside a stream, so I took the opportunity to wash my body and get rid of the filthy stuff from the rubbish dump.

I felt much better after this and kept on walking up the road. By this time I was a bit hungry, so I thought that I would knock on an isolated house beside the road and ask for food, as well as directions into the mountains. There was a man all alone in the house and he received me with great kindness, sitting me down at his table and giving me a nice hot lunch. I asked him the news about the Allied landings and he said that there was a rumour that they had landed at Livorno, and that I should proceed towards there to find out if it were true. I left him the address of my mother in Scotland so that if the opportunity arose, he could write and tell her that he had seen me and that so far I was safe”.

“Did he write to your mother?” I asked.

“Yes he did write after he himself had crossed over to the Allied lines and could therefore write freely. My mother received his letter, but by the time she got it, I was back home and able to write back and thank him for his kind gesture.

Having left my friend, I kept walking up the road that got steeper, and towards the end of the afternoon I was feeling somewhat thirsty, so I called at a farm house where the girls of the family were out picking grapes. I went up to them and we all picked grapes, which I ate with great relish, while the girls giggled and joked about me. They were very kind people, but I did not wish to stay there – being so close to the city. I kept on up the road until I reached the beginning of the Apennines. The people in the farm-house had said that they thought there were other escaped prisoners up in the place towards where I was going, and I found these people sitting in a wood.

I joined them and told them my story. There were two South African

(digital page 9, original page 6)

in the group and two Englishmen, by name of Gordon and Mike. They had escaped from a camp at Padua without much trouble and had already been provided with civilian clothes. After some discussion, we decided that we would go in two groups- the South Africans in one and Gordon, Mike and myself in another. We would head towards the direction of Livorno to see if there was any truth in the rumours of Allied landings. So the three of us headed into the mountains, roughly in a south westerly direction. The procedure was to keep walking all day, halting perhaps at midday for a glass of wine and something to eat at a farm-house, and then keep on into the evening until we could find a place where we could spend the night.

Here in this part of Italy, food was plentiful in the country and the fruit such as grapes, pears and olives were all available. As a rule, we would look for a suitable isolated farm-house where we might be able to stay the night. As we approached such a place, we would ask the peasants working in the fields, whether there were any Germans in the area. The usual reply was ‘No Tedeschi in questo paese’. I can’t think of any occasion in which we were refused food and somewhere to sleep, even though it was in the stables or barn or haystack.

The rumour of Allied landings at Livorno was not of course true, for they were held up around Naples against stiff German resistance, so it seemed that we would have to just keep going, in the hope that the Allies would advance rapidly.

So, Gordon, Mike and I kept on down the west slope of the Apennines skirting Florence, Orvieto, Rieti, keeping to the less populated parts, and never venturing into cities or even villages. At a place called Rocca Sinibaldi, my boots were wearing through the soles , and it became essential for me to have a new pair of shoes. A young fellow called Dante at this place, gave me a pair that were not so new, but at least they, lasted until the end of my journey, for which I am most grateful.

Near Rocca Sinibaldi, we met a group of carabinieri, who had fled from the town because they were being rounded up by the Fascists. They were all armed and were talking about, joining the partisans. We didn’t stay with them because we thought it futile to start partisan activity in that area, which was far from the possibility of Allied assistance. One afternoon, as darkness fell, we passed a group of Germans who had obviously taken over a villa and had parked their transport outside. We did not feel like knocking on their door asking for food, so we passed by looking like labourers going home from work”.

“Were you not scared?” I asked.

“No, just cautious. It was obvious that we were getting closer to the areas where the Germans were more conspicuous by their presence even in a small country villa. Later that evening, we reached the village that

(digital page 10, original page 7)

I now know as Forme, and as it was now dark, we plucked up courage to knock at a door to find out if we could spend the night there. I can’t remember much about the people there, but I know that they sent a boy with us to guide us to a small shepherd’s hut outside the village, where we lay down quite tired on the straw and waited further developments. Next morning we awoke from our hard beds and heard a low whistle coming from somewhere nearby. We popped our heads out of the hut and saw a man standing about fifty yards away, who called to us to come out. We went towards him and we introduced ourselves as three English Officers making our way towards the Allies.

He was a tall handsome gentleman, dressed in well-cut country clothes and he was accompanied by a striking-looking lady with reddish hair, and wearing an elegant trouser suit. The gentleman spoke excellent English and asked us where we had come from end what we were planning to do. He posed some questions about sporting events in England – such as who won the English cup that year, and in which parts of England we had lived. We suspected that these questions were put to us to make sure that we were truly English and that we were not German infiltrators.”

“Well, that’s funny because you must have been thinking the same about us”.

“No, I don’t think we would have thought that, but we were indeed surprised to meet such a distinguished couple in a little isolated village under the shadow of Mount Velino, whereas up till then we had only spoken to the peasants in our very poor Italian.

Then the gentleman introduced three young ladles, who had till then been sitting behind some rocks, and our eyes nearly popped out of our heads when we saw three girls in their late teens or early twenties coming towards us. They were dressed as if they were going to an apres-ski party; one had fair hair, one dark hair, and the third chestnut. Imagine what it was like to see these gorgeous girls after being shut up in a prison without female company for so many months. The gentleman introduced himself as Mr Nathan, his wife Peggy, and three daughters, Amelia, Giorgina and Virginia”.

“Yes, and do you remember when we came back in the afternoon to have tea. When we gathered the wood and lit a fire and made tea?, and also brought you some of our very few discarded clothes which you had asked us for, as you were all suffering from the cold weather up there in the mountain gorges. We had gathered the very few ones we could ourselves afford to part with, since we also had to escape with just a handful of belongings due to our having to leave Rome at short notice.”

“Why did you all have to escape to this isolated place?. I remember

(digital page 11, original page 8)

you telling us at the time, but I would like you to refresh my memory”.

“Well, my father was Jewish and my mother as you know, Australian. Both of these things were, for the Fascists, enough to consider us enemies. The Jewish persecution started in 1938 and we fled to Australia, but because of some rather odd circumstances, we came back to Italy in 1939, and were prevented from leaving since they took away our passports. We lived a quiet life on our farm near Tivoli till the Germans occupied Rome, Then it became a matter of life or death as my father was one of the first names on the German hostage list in Rome. We had to clear out in a matter of hours, carrying only a few garments each. We went to Forme because a family of shepherds, who used to come down and rent my father’s grazing land each year, had told him if in difficulty, he was welcome to come to their village up in the mountains with all the family. When we realised how difficult it was to hide five people in one place in Rome, father decided that we would chance coming up to this remote village.

We were pretty sure that the Germans would never come to this isolated place. In fact, two of our Italian friends, Manlio and Sergio, joined us there to escape capture from the Germans, as they were officers in the Italian army. You know all about them, having left together from Forme to try and reach the Allied armies. Now you must tell me what happened to all of you.”

“Well, after saying goodbye to Mr and Mrs Nathan and the three girls, we started to walk in what we thought was the safest way to proceed towards the battle lines. Our route took us towards Avezzano, but before reaching that place, we diverged over the low-lying plain around Avezzano, and headed up again into the mountains opposite. All this time Sergio and Manlio were leading the way to ensure that we were not falling into an area where it was dangerous for to go. We three, Gordon, Mike and myself, followed at some distance behind so that if there were any danger, we could lie low until it was all clear.

So, later on that day we reached Villa Vallelonga. Manlio and Sergio went ahead into this village and found a house where people were prepared to give us shelter for the night. The next morning we walked further up the mountain and in the afternoon we reached the summit, where there was a little stone hut which I guess was for the benefit of climbers or skiers. On the way, we had bought a lamb which had been butchered, and that evening we gathered firewood from around the hut, to make a fire and to roast the lamb. So that night we dined on good roast lamb and potatoes cooked in the ashes. It was very cold up there and the hut was surrounded by mist, but we were warm sleeping beside the fire. The next morning we walked from the

(digital page 12, original page 9)

summit down into a little valley and on towards a village called Campoli Appennino, where again Sergio and Manlio went ahead and arranged for us to stay the night at a house in the village. The owner of the house was an old man called Pietro Fantauzzi, who was a great character and spoke broken English with an American accent as he had worked for some years in the meat industry in Chicago. He was full of curses for Mussolini and the Germans and usually ended up with a few choice phrases ‘Porca qui, porca li, brutti tempi e brutta vita’.

However, our luck was about to run out, for the next morning as we were sitting down for breakfast, a boy ran into the house screaming ‘I Tedeschi, I Tedeschi’ ( they are coming up the road.) We left our breakfast in a hurry, ran out of the house and down into a gorge, which ran up towards the mountains at the bottom of the hill on which the village stood. Meantime, the German patrol had arrived and opened fire on all the Italian men who with us streamed out of the village. In the gorge we saw a cave in which we thought we would escape detection, so we went inside hoping that the Germans had not seen us go in there. But in a few minutes we heard German voices outside the cave and there was no doubt that they had seen us, and required us to come out. By the tone of their voices, we expected any minute to have a grenade thrown into the cave. As discretion was the better part of valour, we decided that we had better come out quickly with our hands up. The Germans surrounded us and led us back up the hill into the village. On the way, we saw that they had shot an old Italian man who was bleeding profusely. They had rounded up about twenty Italians of middle to old age including the village priest, who with us were put in the back of the German truck.”

“What happened to Sergio and Manlio?” I asked.

“They must have gone faster than us up the gorge and did not go into the cave which we went into. As they were not among the Italians captured, we assumed that they had got away, for which we were truly thankful, as any connection with us would have probably proved fatal for them. The Germans took us all down to Frosinone and put us in the town jail, which was a filthy place. We were all in the one room and the Italians were most unhappy, particularly as they may have been suspected of helping us. We tried to sleep that night on the hard beds but the bed bugs were so ferocious, that there was little chance of sleep. I would not have liked to have stayed in that place very long, because every now and again, the chief jailer would come into the cell and start shouting and raving at us. We had by then admitted that we were escaped POWs but gave no further details of how we had come to be at Campoli, nor the names of anyone who had helped us. Later that day, German soldiers came to the jail and escorted the three of us down to the POW cage that had been erected in the

(digital page 13, original page 10)

town. Most of the prisoners there, were Americans from the Fifth Army front which was further to the south. A few days later, most of the prisoners in the camp, were marched down to the station and put into cattle trucks in the usual fashion. The train moved off eventually and had gone up the track for maybe half an hour, when we heard the sound of planes overhead and of bombs dropping. The train stopped and someone managed to open the door of the truck and we all jumped out, scattering in all directions away from the train, I found myself alone again, separated from Gordon and Mike, and as quickly as I could, I ran across open country and up into the woods.

I kept walking as fast as I could seeking the highest ground as far away as possible from the railway line. It was getting dark when I reached a farm-house and I knocked on the door to find if I could shelter there for the night. The farmer and his wife were very frightened, but he put me in one of the out-buildings of the farm and said I could stay there till dawn. Before I could get to sleep, the farmer came in very agitated and said the Germans were searching all over the local area. He took me to a small wood and left me there to spend the rest of the night. He came at dawn with some food and gave me directions into a more remote part of the mountains. At this stage I had no idea what to do, so I decided that the best thing would be to make my way back again to Campoli, where I was sure that Pietro would look after me. This I did in about three days hard walking, the only dangerous part being the crossing of the Liri Valley near Balsarano. I reached the outskirts of Campoli late one afternoon and met some of the women of the village washing clothes at the fountain. I asked about the men who had been taken from the village and they said that they had all been released and come home.

I then went to Pietro’s house and he gave me a great welcome, as usual cursing the Germans and Mussolini and the Fascists all in one breath. In view of what had happened, it was not safe to stay in the village, so Pietro put me in a little hut he had down in the valley where he grew vegetables. By this time the weather was getting quite cold, particularly at night, and I felt that it would not long before we saw snow on the mountains. Also, the Germans were increasing their patrols, coming up to the village almost every day and sending soldiers up into the mountains to look for escaped POW, of whom quite a number were hiding in that area.

I had met another escapee called Ginger, or Lorenzo to his Italian friends, and with him I shared Pietro’s hut, which we would leave early in the morning to hide up in the mountains, all the time watching for the German patrols. At dark we would return to the hut, and Pietro would bring us hot food and any news that he had about the Allied positions, We thought of waiting there until the Allied armies reached that area, but as the days dragged on, there did not seem to be any major advance towards the north.

(digital page 14, original page 11)

We then decided that the only thing to do rather than spend an uncomfortable winter in that place, was to make a forced march across the mountains to eventually find an Allied unit. And so I asked Pietro to buy and cook some meat to sustain us for several days, giving him the money I had hidden in the seam of my trousers since Bologna.

Pietro was as good as his word, and drought us some meat which I packed in my haver-sack, and we set out saying many goodbyes and thank yous to Pietro for his kindness. At this point, we were joined by a British Sergeant called Andy, and the three of us set off from Campoli towards our destination. We had to cross a valley by night because we could see from above that there were many German vehicles using the road across the valley. That trip was a nightmare, as we had to cross country blind and often had to wade through streams and marshy places to get to the other side. By dawn, we had crossed the valley and went through a small village with the dogs barking at us all the time, then along a road past an old monastery, and eventually came to a ruined building in the middle of nowhere. There we found many Italian men who were obviously evading capture by the Germans who took anyone they could find for forced labour. It was an uncomfortable night and we were glad to get out of the place. We kept along the edge of the mountains just below the snow line and all the time could hear guns booming in the distance.

The third night, we spent in the hay barn of a small village, which again was crowded with refugees. The next day we kept on walking as far as we could ascertain towards the south and now and again, we could see German soldiers further down the slopes. In the late afternoon we came to a clearing in the woods, in which there was a small shepherd’s hut. There seemed something evil about this place. I looked into the entrance of the hut, and there before me, I saw about six men dressed in shepherd’s clothing staring into space with eyes that gave no sign of life. The evil in this place seemed to envelop the hut and somehow I felt that if we stayed any longer, we would he killed like those shepherds were. God knows by whom. So I said to the other two ‘Let’s get the hell out of here before we end up like that’ and so we did.

We now started to descend into a valley, passing by very cautiously, a house in which we heard Germans talking. We reached the road at the bottom of the mountain and walked along it carefully, ready to jump into the bushes if anyone approached. It was now quite dark, and as we passed along, we saw that all the houses along the road had been abandoned and their doors and windows were flapping in the wind. There was a river running alongside the road and when the road came to a bridge, we saw that the bridge had been blown. So we had to wade across the river at

(digital page 15, original page 12)

various points. Fortunately the river was quite shallow there, and we only got our feet and trousers wet.

Eventually, we sow a light in a house beside the road and decided that the best thing was to find out where we were and where the Allied troops had reached. So I knocked on the door, keeping well out of the light, so that if it were opened by unfriendly people, we could make a quick getaway into the dark. A man came to the door with a shotgun in his hand, and I asked him the usual questions that is: where we were and if there were Germans in the area. He said ‘No, the Germans had gone, but it was too dangerous to venture further, as there were patrols from both sides ‘operating at night.’ We went in the house where he had a roaring fire going, and although we were not sure at first whether he was telling the truth, he more or less convinced us by producing currency issued by the Allied military government. Upon this, Andy somewhat reluctantly, produced a tin of porridge which he had been saving all this time, and we cooked this over the fire and celebrated.

We spent the night once again, in a hay barn with many other refugees and in the morning, the man escorted us along the road for about four miles until we reached an out-post of the British army in a small village. He took us up to the commanding officer, we said goodbye and thanked him and then were taken over by the Army.

After some interrogation to make sure that we were genuine, we were sent down the lines in a jeep, and by various stages reached a reception camp for escapees at Bari, where a year ago I started my enforced stay in Italy. After delousing and a new set of uniform, I was interrogated again by intelligence officers, before being shipped over to North Africa. I spent Christmas in Algiers, where surprisingly, there was a group of Russian officers in the mess who kept strictly to themselves and wouldn’t talk to us. We spent New Year’s Eve on board ship heading for England, and in early 1944 reached Liverpool, and on to London by train where were issued with all the necessaries of war time Britain, such as ration books, clothing coupons etc, and then sent on several week’s leave. I went back to my parents in Scotland, who were most overjoyed to see me because when I escaped at Modena, I was posted as missing and they didn’t hear any more of me until they received a telegram from the War Office saying that I had re-joined the British forces. So, that is the end of my story. What happened to you and your family?”.

(digital page 16, original page 13)

Well George, as you know, the Germans did eventually come to Forme and made their headquarters in the house opposite where we were hiding. This created quite a problem for we did not feel secure any longer. After warning all the escaped prisoners in hiding up in the mountain, who also then made their way south to try and reach the Allies, we decided that our best chance would he to go back into Rome.

The problem was to find places for all of us. We had to split up of course, and we all hid in different places. My father was later captured by a Fascist group that was operating separately from the Germans. They held him first in Via Tasso, the infamous torturing head-quarters, and after that, to the main prison of Rome, Regina Coeli. Fortunately, they did not torture him. Many strange events happened to us all, so many that it would be another story. In brief, father was liberated when the Germans left Rome and we were freed by the Allies. Both mother and I were then hiding in a convent and were mighty pleased to see the Fifth Army occupying the streets of Rome. We had many very unpleasant moments and frights. We were the lucky ones for we all came through that terrible year alive. Even today, I can’t without shuddering, think of what we risked and of the millions of people who ended up in the ghastly extermination camps. I guess we have both been through a most unpleasant experience.”

“What happened to Sergio and Manlio. Did they manage to get away from Campoli?” asked George.

“Yes, they managed to get away and make their way back into Rome, stopping off in many small mountain villages. Manlio was able to find the place where I was staying, and joined me there. Sergio was taken in by some friends, and we used to meet secretly with Giorgina and the four of us would go and have a beer in the Dreher restaurant in Piazza Sant’Apostoli. That particular place was frequented by Germans, and for that reason we considered it the safest place to go into, because the Germans would take no notice of two couples sitting at a table drinking beer, probably thinking us to be German sympathisers.

I am so pleased that tomorrow we are going back to Forme to see the old places and also to see if anyone of that period is still alive. It will be a most interesting experience”.

“I would also like to go down to Campoli to see if old Pietro is still alive or some of his family still live there. We can get there through Avezzano down the Liri Valley and then back by Frosinone, Zagarolo and Tivoli.” Said George studying the map. The same, old map he used forty

(digital page 17, original page 14)

plus more years ago. So I suggested that we retired to our bedrooms early so we could have an early start. We drove up the following morning along the new Aquila Highway to Magliano, and then up the winding road to Forme. We suddenly came across the tall looming peak of Monte Velino; the blue sky indicated a fine summer day. The sun was hot and made the small village of Forme look clean and new. We both remembered it grey and old with winding steep steps and narrow alleys. The old goat track that I had been driven up in a rusty old cart, pulled by an old mule many years ago, was barely visible over the hills. A new asphalt road now wound it’s way up and through the village. The whole place had changed, but not in my mind, for I spotted immediately all the old places. The old grey house where we lived during the daylight hours, still stood opposite the house occupied by the Germans, and was now redecorated. We stopped the car and I got out. Cono, a friend of mine who had driven us up, and George, waited in the car as I approached a man walking up the side of the house towards us. I recognised him at once, for one could hardly forget the impressive figure and features of Alessandro Cofini. I did not know what his reaction would be and thought it wise to just ask after the Cofini family. He looked at me with his acute hawk-like eyes and a flicker of recognition flashed through them. I then could hold back no longer and said “It is Virginia Nathan”. He hugged me and kissed me and immediately we were all escorted into the house. Nannina his wife, had run downstairs to welcome me. We were almost in tears of emotion for this incredible moment. We sat in their living room, the same one but now changed. Modern furniture had taken the place of the large dining table and the corner fire place where the woman used to cook our meals. The window looking onto the German headquarters was still there, and I walked out onto the balcony to look once more at that same window. A flash back of two fair-haired German officers came back to me.

We sat and had coffee and our friends told us all about their family. Most of them had died, Alessandro couldn’t get over the emotion of seeing me again. I was still for them the Signorina Virginia. I told him that I had recognised him on first sight, and he jokingly put a hand over his prominent long nose and said “With this philosophy ?” meaning the Italian word fisonomi, getting it all muddled up. We laughed and left them, and before going up into the mountain to find the place where we had met, we walked down to the other house where we used to sleep, and that one had also been redecorated. We drove up the road till we reached an open space where there was a cattle trough which I immediately recognised. From there, we walked up the narrow goat track where scattered rocks emerged. “These are the rocks” I said, “I recognise them”.

(digital page 18, original page 15)

It was a breath-taking moment. Monte Velino stood right on top of us and we could see the many crevices and caves along it’s ridge. George was also looking around, trying to spot the hut they had slept in. A triangular field of poppies broke the pale green grass, now turning yellow. Some poplar trees still stood in their original place near the new road leading to Ovindoli. We looked over the mountains and valleys as we took out our cameras and started to take photos of each other. This was the moment, the moment we had waited for. Over forty years had passed, but for George and me, the clock had gone back and we were two handsome young people sitting around a fire drinking tea. Mother and father came vividly back, they were also there with us and so were Mike and Gordon.

Young Cono, who accompanied us to Forme had captured the meaning of the moment, and kept saying ‘Mamma mia’, I get goose pimples to think of you forty years back’. ‘What a moment’, he kept repeating. Then the magic moment had gone and we were hack in the car heading for an eating place to have some good mountain food. Our legs were not the same ones that had skipped and ran up that mountain slope forty years ago.

We found a nice little country restaurant – Chalet Velino – not far from Forme and had a warm welcome as we settled down in front of Rigatoni Strascinati, their speciality, and a good bottle of vino da pasto. The owners were very interested in our story as we inquired about the best way to reach Campoli, our next stop.

We left the Magliano plain feeling satisfied and happy as Cono headed for Avezzano and then up into the Apennine mountains that ran above the Liri valley. He drove us skilfully on the winding roads, up and down the side of the steep mountain chain. Small villages perched upon the summits overlooking the River Liri, that meandered it’s way slowly through the valley. Then we saw a superb castle half way up the hill before reaching Balsarano and then on to Sora. From there we turned into a very steeply curved road that took us into Campoli. This old village extended along a mountain ridge overlooking two valleys. On the one side a large round crevice, once a volcano, but now hollow with only rubble and arid grass, looking as if it was waiting to be transformed into a lake.

We stopped a couple of old people who were walking along the roadside and asked for Pietro, the kind old man who had given George refuge. They listened to our story and sadly shook their heads. Pietro had died many years ago, and only his grandsons now came up to the village occasionally. They pointed towards the house in the village square, so we drove on up to where it stood. We got out of the car and looked at the house, which was gleaming with new coat of paint, and then went over to the terrace wall that overlooked the valley and the gorge where George and

(digital page 19, original page 16)

Manlio and Sergio had fled when the Germans entered the village. The same gorge went up into the chain of Apennine peak. Two or three people came up to us as George recalled everything that had happened to him. The old couple whom we had talked to earlier, then joined us and we all gathered to relate the various episodes way back in 1943. They also told us that a few days back, some Germans had come up to Campoli doing the same as us. They had opened barn doors, and walked along side streets evidently also nostalgic for their last stronghold before their final defeat.

George very sad about Pietro not being there to greet him, I am sure that he felt that maybe somehow, Pietro was present after all, as he took out a lapel pin with a Kangaroo, symbol of Australia, and pinned it on one of the old men, asking him to give it to Pietro’s grandson when he next came up to Campoli. Having done this, we left the old people and after touring the main piazza, left Campoli.

We drove back down towards Sora and then on to Isola dell’Liri, where we stopped to admire the Boncompagni Castle with it’s waterfall. We re-joined the Naples highway till Veroli, and then took the old country road back through Palestrina and Zagarolo, hitting the hot white track through Galli, and back home to the welcome of my five dogs and five cats.

George and I sat outside in the evening breeze, sipping our drinks and recapturing all the most impressive moments of that day. We were both happy, for now we had been able to complete something that had been in the back of our minds for forty odd years.

“Well George”, I said, “Part of your trip is fulfilled. Tomorrow you will be in London and next month back home to Perth”. “Yes, I am very pleased that I managed to see all those places. Maybe we could go back there again sometime in the future for further investigation, although I doubt that we could walk along any of the steep ridges “.

I laughed, “I doubt it too, I think we would have to hire some mules if we ever decided to retrace some of your three hundred mile walk down the Apennines”.

We called it a day, and next morning George was all packed and ready to leave. It was sad to say goodbye, but I felt sure that this time we wouldn’t let another forty years go by, for this was only the beginning of a life-long friendship.

We came to Forme from different directions and for different reasons and we met and talked and laughed for a brief spell, before we left to pursue our separate destines. Was it mere coincidence or the hand of fate that led us to re-capture those memorable times, when once again we came to FORME?

(digital page 20)

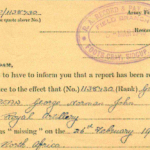

(photograph of Virginia Nathan and George McHattie, handwritten caption reads:) After forty years – 1984. Both of us revisiting “Forme” where we used to have our tea parties with the POWs.

(photograph of George McHattie, Gordon Clover and Mike Williams and two Italians. George McHattie is second from left. Rare photograph of escaped POWs in Italy. Caption for photograph is on digital page 55)

(digital page 21)

(handwritten letter addressed to Virginia Nathan from Gordon Clover)

Denbigh, North Wales

14th March 1946

Dear Virginia, How glad I was to hear from you and to know that you and all your family are safe and sound. I have many, many times though of you all and remembered with pleasure and gratitude your many kindnesses. I did not remember your address (which I had not written down – for obvious reasons) but I remember that you had a farm, North-East of Rome, the name of which had something to do with “cockerel” is that right? When I reached Naples in July 1944, I had to make a report and I told the authorities all about you. I could give a description of which you could be identified (2 words illegible)

(digital page 22, original page 2)

that your father had something to do with Bank of Rome. I hope that someone in Italy, on behalf of the British, had officially thanked you all personally. I should not be surprised if you all had a worse time than we did. I am very sorry to know that your father fell into the hands of the Fascists and that he has not recovered from what he went through. How vividly I remember him and his kindness! I have never heard what happened to Sergio and Manlio and I do not know whether you know their story. Briefly, we got separated from Manlio and after some delays pushed on with Sergio until by some bad luck, we ran into a “retata”(?) in Campoli. Sergio got outside the net and we inside. Mac (George McHattie) and I got away separately a week later when

(digital page 23)

the train was boarded at Colleferro (North of Frosinone) and Mike Williams was carried off to Germany. I should so much like to know whether Sergio and Manlio are safe and sound. We eventually borrowed quite a lot of money off Sergio, or rather he paid out a lot for us, buying a sheep once and other food. If the authorities were able to find him from my description he will have been repaid. I do not suppose for a moment that he gave the matter a thought, but one likes to pay ones financial debts. The other debt, the debts of gratitude go many people, one can never repay. This is something that I feel one could say better in Italian or French than in English, but I had better stick to English. In my heart there is and will always be

(digital page 24, original page 4)

feelings and gratitude to all your family. The association with you was one of the happiest interludes in those mixed and anxious times. You may remember that Mac and I spoke a little Italian atrociously and that Mike spoke none at all. Though I say it myself, my Italian vastly improved. The Italians I met eventually said how well I spoke it, and though I discounted 99 percent of that for Italian politeness, I did learn quite a lot more! I spent some time in a “capanna’ above Sergio and then five months in Rome until the arrival of the Americans in June. I was unwell for a long time when I got back to this country but I am pretty well O.K. now and (1 sentence illegible).

(digital page 25, original page 5)

I do greatly hope to come to Italy again some time. When it will be I do not know. Transport and getting money out of this country will be the difficulty. Perhaps you will be in England before I am in Italy. Will you be able to let me know if you come as I hope you will? If and when I come to Italy I shall certainly come and look for you all. Again I say how glad I was to hear from you. I hope you will find time to write to me again sometime; you haven’t fully told me very much about yourselves. I presume that at some time you left Forme. Wasn’t there a lot of fighting in that valley and around Magliano? (3 words Illegible)

(digital page 26)

I will write again, if I may. May I send my love to all your family and to you? Yours ever Gordon Clover

(digital pages 27-28)

(photograph with caption:) George with Cono, the driver friend of mine at Campoli.

(digital pages 29-30)

(photograph with caption:) George at Campoli where they escaped down the valley where the Germans cornered them in the cave.

(digital pages 31-32)

(photograph with caption:) George and me up at Forme where we had our tea parties!….

(digital pages 33-34)

(photograph with caption:) George and me at the same Campoli Valley.

(digital page 35)

(letter from George A. M. McHattie to Mr and Mrs Nathan, parents of Virginia Nathan)

G. A. M. McHattie,

London SW1.

12th January 1946

My dear Mr and Mrs Nathan,

This letter is long overdue as I got back to England in January 1944, two years ago. You will remember that in October 1943, three British officers arrived at a small village where you were staying, just north of Avezzano. You were of great assistance to use and were very kind in spite of the danger involved. You will recall that we set off, in company with two Italian friends of yours to cross over to the British lines. A few days after that we were captured by the Germans. Sergio, your friend, got away in time, but we three were taken. Eventually we all escaped again from a train, but Mike was recaptured,

(digital page 36, original page 2)

Gordon was separated from me and Mike and stayed in the hills until freed by the Anglo-American advance on Rome. I managed to get over to the British about three weeks after I last saw you.

I have been soldiering again and it was only when the war ended in Italy that I was able to write to you, and only now when I find myself demobilised and again a civilian do I find time to send you my very best wishes. I trust you will forgive me my ingratitude, and that this remissness of mine is at least balances by the fact that this first year of peace finds you all safe and in good health.

I committed your address to memory when I left you and definitely meant to write to you, but as I left Italy

(digital page 37, original page 3)

Very quickly I never was able to pay you a visit. I hope therefore that this address find you at your old home.

Mike, who was recaptured, was taken to Germany, and was freed when Germany capitulated. I gave seen him since he came back, and he seems none the worse. Gordon also got back safe. I hope that all you friends eventually reached safety, and that your home is secure.

Please accept my sincere apology for not writing earlier, and my best wishes to yourselves and all the family.

Yours sincerely,

G.A.M. McHattie

(digital page 38)

(letter from Virginia Nathan to George McHattie)

Virginia Nathan

Rome

27th January 1946

Dear Mac,

you have no idea of the joy we had in getting your letter. We have been so worried about you all and we were afraid to write to your houses as we had no idea whether or not you were home and were frightened to bring sorrow to your families in case you had not got home safely. But, now that we have the pleasure of knowing you are well and safe I will certainly write to you and keep up correspondence if for you it is o.k. We are all safe and very

(digital page 39, original page 2)

much alive. We have been through hell, after you left as we went back to Rome and hid there. Our father was taken and put in jail for a month and was lucky to get out the day the Allies came. We then all got jobs and worked for more than a year. Giorgina my fair sister is still working, she got a very good job in the Public Relations Office and has done various jobs, (such) as journalist work and other interesting things. She got married in July of 1945 to an American War Correspondent, a very nice chap and not a tall a Yank type. Amelia, my elder sister is very well

(digital page 40, original page 3)

and is living with us now as her husband is studying to get his medical degree. My mother is very well and got quite fat and young again. She is on our farm near Rome and has had a terrible job in getting the place together again, as we had damages and shells all over the place.

My father has taken back his old job in the Bank of Italy and has a great deal of work to do. He comes to the farm for weekends. And I live a bit on the farm and a bit in

(digital page 41, original page 4)

Rome. I am the only sister left now and have no intentions of getting married. The two friends of ours that went away with you have eclipsed from our household, thank God for that and we have now made a lot of new friends among the Allies. We have had a lot of very nice parties this year and life is quite pleasant. It would certainly be very nice to see you again. Do you think you’ll ever get a chance of coming to Italy again? I always have

(digital page 42, original page 5)

hopes of coming to England, but I don’t somehow think it will be very soon. Do write and tell me what you do now? I suppose your family must be terribly glad to have you home after such a long absence. I pass my time in painting and working about the farm. I occasionally ride. In Rome I am quite occupied as I give a few English conversation lessons to friends and go to a gymnastic class with my sisters and do exercises to try to get a bit slim as I am very fat!!

(digital page 43, original page 6)

It’s certainly marvellous to think that we have all escaped such terrible perils. I shall write to Gordon and Mike. Well Mac, we would have such a lot to write about, but I must now come to an end. I do hope to hear from you again. My family sends you their love that is to say Pap, Mar, Amelia and Giorgina and so do I.

Virginia

Send letters to the address I wrote on here as they get these letters.

(digital page 44)

(letter from George McHattie to Virginia Nathan)

G.A.M. McHattie

London, SW1

12th February 1946

My dear Virginia,

I was very pleased indeed to get your letter and to learn that you and all the family are well, and I think we can all consider ourselves extremely lucky to have got off scot-free from the adventures of the last year or so. I have told you what became of Mike and Gordon, now both back in England. Gordon I have not seen in person but I had a letter from him shortly after he got back to England. Mike, however, I saw just a few days ago. He is still in the Army

(digital page 45, original page 2)

and he was spending a few days leave in London. He did not fare too well in Germany, and was very thin when he got back, and his spirit was a bit morbid. He has, however, made a rapid recovery, and he was enjoying himself like anything chasing about after the girls. I guess you would hardly recognise us if you saw us perfectly shaved and dressed, for we must have looked absolute freaks when you saw us in Italy.

I have put at the end of this letter the last addresses I have of Gordon and Mike, so that you can write to them if you wish.

We are more or less getting used to peacetime in England, but as yet

(digital page 46, original page 3)

many wartime conditions remain.

Food and clothes are still strictly rationed, and the ration is not likely to increase for some time yet, in fact it is possible that our food may be reduced to allow for supplies to be sent to Europe. Drink and cigarettes are fairly plentiful, but expensive, and income tax will be very high for many years to come. And so we pay for the war which benefitted nobody. Still, with the blackout gone and the prospect of summer ahead, things don’t seem so bad.

I myself was released from the Army (or rather the RAF (Royal Air Force) as I have been flying since I got back) a few

(digital page 47, original page 4)

weeks ago, and am not a civilian. I have started work in London at the Air Ministry, and I shall be living here for some time anyway. I find sitting in an office very difficult after all the years I have been up and about all over the world, but I suppose I shall have to get used to it in order to earn my living. Work is much harder that it was in the Forces, and I have to use my brain a great deal nowadays, which I admit I hadn’t to do very often in uniform, and consequently at the end of the day I feel quite tired. There is plenty to do here, of course, in the way of entertainment – films, plays, dances etc – but

(digital page 48, original page 5)

at the moment, while I’m settling in to my new job I’m taking things fairly easy. My original home was in Scotland but it looks as if I shall be living in England meantime, and that I don’t mind at all.

I wish I could come to Italy and see you all again. There are many Italian families who helped us when we were in need, and I wish I had the opportunity to thank them all in person. God knows when it will be possible to travel freely again to Europe – at present everything is dependent on the military situation, but I dare say in time it will be free as before. I should love to come to Italy for

(digital page 49, original page 6)

a long holiday, just to revisit the places that stick in my memory, and to enjoy the scenery which we were unable fully to appreciate when we had to see it under very different circumstances. It’s a beautiful country and a wonderful climate (England has an awful climate, I think, for I like the heat), and perhaps one day I shall be able to return. And if you ever happen to be in England do look me up.

I’m very glad, Virginia, to hear that you are happy, and from your letter I gather that you are a very busy girl these days. I suppose your sister Giorgina will be going to the States in due course, and Amelia will

(digital page 50, original page 7)

be settling down to married life. But what about yourself? I can’t imagine that you are going to be an old maid by choice. In fact I’m sure you like men a bit more than that.

Your English should be perfect by now, though, as far as I remember, it was as good as, if not better than mine, when we met you. I’m sorry you have to take some horrible exercises to remove surplus flesh – surely there’s no need for that?

Winter will soon be over – I hope – and I should imagine that summer will be a far more pleasant time in Italy. Maybe by then things will be more

(digital page 51, original page 8)

organised and you will have a more stable government and increased production, which is probably what Italy needs to make her well again.

Meanwhile I’d be delighted to hear from you and learn how the family are doing. Please give my love to all of them.

All the best,

Yours,

Mac.

p.s. My writing is pretty bad and if you can’t read it or don’t understand any phase I use let me know. M.

(digital page 52)

(Photocopy of title page of ‘Roma 1943-1943, Una famiglia nella tempesta’, an account of Virginia Nathan’s experience of war, published 1997.)

Virginia Nathan

Roma 1943-1943

Una famiglia nella tempesta

Prefazione di Francesca Boesch

Introduzione di Maria Immacolata Macioti

(digital page 53)

(repeat of photograph on digital page 20. Photograph of George McHattie, Gordon Clover and Mike Williams and two Italians. George McHattie is second from left. Rare photograph of escaped POWs in Italy. Caption for photograph is on digital page 55)

(digital page 54)

(short biography of Virginia Nathan’s grandfather Ernest Nathan:) Ernest Nathan, 1845-1921, born in England and became Mayor of Rome 1907 for seven years. Wife Virginia died in 1924. A Jew and a Mason. Public Education More schools, less churches, public transport, building restrictions.

(digital page 55)

Manlio and Sergio, two Italian Army officers with Gordon and Mike had escaped from Padua with George McHattie now of Perth Australia.

(caption for photograph on digital page 20 and 53:) Three obvious Englishmen between their Italian guides – George McHattie with scarf.

(handwritten note:) North of Acezzano Forme under Mount Velmo.

Lucia Sponza

(digital page 56)

Mr Colin MacHattie,

Oklahoma USA

6th April 1999

Dear Mr MacHattie,

I was sad to hear of your father’s death but glad to know that he heard of how his own story linked to that of Virginia Nathan had so greatly interested the family of Gordon Clover who was a ‘fellow bird of passage’ in Italy.

I had only just written the piece about the Clover family wanting to know more about Gordon in Italy when in came out of the blue the story of your father and the remarkable photo from Virginia Nathan. As I read the letter there seemed something familiar.

There are very few photos of POWs while ‘on the run’ in Italy in our files — partly because few had access to films or cameras and also for security reasons. Being six foot plus myself it was obvious on my fourth capture that I was not the Italian I claimed to be, but the photo shows clearly how difficult it was to pass oneself off as Italian.

You seem to be a well travelled family. I called at Freemantle on the first boat to leave Australia after war was declared as I had been for two years in New Zealand as a cowboy roustabout. Though not to Western Australia I have been back visiting friends in other parts in recent years but Italy is – or now I must say – has been my main stamping ground.

If by any chance you have anything your father wrote about his time ‘on the run’ in Italy we would very much appreciate a copy for the archives of the Trust.

Again my sympathy at your sad loss but I am sure you have happy memories of a much travelled father.

Yours sincerely,

Honorary Secretary,

Keith Killby.

(digital page 57)

Virginia Nathan

Wimbledon

10th May 1999

Dear Virginia Nathan,

Enclosed is a slip that I have sent to the many people who responded to the Annual Report. Only to-day can I begin to catch up with some of the more important ordinary correspondence.

Stephen Clover has been so pleased with what we have been able to tell him about his father thanks to you. I was able to call on a family who had helped him and to find to my surprise that the Italian on the right – the taller of the two in the photo was Novelli the father of the family who had helped them and had the photo taken. The other they thought to be a young Jew who was later captured and died in that terrible massacre in the Ardeatine Caves.

However there was another interesting event during my visit to Rome. I went to dinner with old friends the night before the function at the Embassy and I told them about the coincident with your family and the Clover family. I mentioned that your grandfather had been Mayor of Rome. At that my hostess disappeared and came back with a copy of the book ’Ernesto Nathan, Il Sindcao checambio il volto di Roma’.

I was able to look at and found it very interesting. It was an amazing achievement to have been born a foreigner, to have been a Jew and a Mason and to have been elected Mayor of Rome. Of course up to the time of Mussolini joining with Hitler there were Jews in public life in Italy as here. I noted that he had put much emphasis on education and I liked the expression ‘more schools and less churches’ – though of course in the late nineteenth century there was surge of building churches here by various protestant and Church of England groups. Then he managed for the city to take over the trams and passed laws to stop the city on invading the countryside – long since defied unfortunately.

Obviously your grandfather was a very modern man.

This weekend I have to go up to York to functions connected with POWs and the various people who helped them in various parts of Europe. Next week I hope to have a little more time to call my own. I shall therefore telephone you to see if it might be convenient to come over and see you. Is there a small restaurant in easy distance from you where we might go for lunch?

I will phone and I hope we can arrange to meet.

Yours sincerely.

J. Keith Killby. (Honorary Secretary)

(digital page 58)

(The original file at this point includes a copy of an Italian newspaper ‘Il Messagero’, 11 February 1998, recounting Virginia Nathan’s story of escaping from Rome during World War Two. Her Father was a prime target of the Nazis. The newspaper article has not been published due to copyright but it can be consulted in the original file. Please contact the Trust if you wish to view it).

IL MESSAGERO

Culture and Entertainment

DYNASTIES / The granddaughter of the first lay mayor of Rome, British, 73 years old, remembers her cosmopolitan family, Italy and Mazzini’s cult. As well as the anti-Semitic persecutions, now recalled in a book

‘THE LESSON OF FREEDOM OF GRANDFATHER NATHAN” of Patrizia Saladini

The face is that of a romantic English woman. With an Anglo-Saxon delightful humour recounts, in the book “Rome 1943-1945. – Una famiglia nella tempesta” (A family in the Tempestuous times) published by SEAM, a dramatic Italian story.

Virginia Nathan, from London, 73 years old, daughter of Giuseppe (called Joe, high official of the Bank of Italy till 1938, when he was dismissed because he was a Jew, because of the racial laws; granddaughter of the first layman mayor of Rome, Ernesto Nathan, she does not pretend to be a writer: “Many years ago I started writing children’s and short stories. Now I write to remember the events of my “tempestuous life as a young English Jew”.

Her life has been alternated by riches, persecutions, escapes, pain, joy for being free once more, and finally, a dignified poverty. Now Virginia lives in Wimbledon, South East of London, in Worple Road in a mini-apartment for old people.

“I am a guest of the British Government, and I have to thank Queen Elizabeth”, she says smiling. “However, my heart is in Italy, where I have spent painful years but also some wonderful ones”. Friday at 5pm she will be a guest of the small Protomoteca of the Campidoglio where her book will be presented. The Mayor, Francesco Rutelli, has already said that he would like to speak to her privately to know more about Joe’s story, the harassing moments he spent as a recluse in March 1944 in Via Tasso, and of the Nathan family.

“Memories of my father are still very vivid in me as well as that of my mother. She was called Peggy, she was an Australian artist, slightly eccentric. She always managed to attract attention. When we were in our farm house ‘ I Galli’, near Tivoli, where I lived my adolescent years, she used to ride a horse and shocked the people by perilously galloping away. Mother had known grandfather, Ernest, just before he died in 1921. I was born in 1925 and I only got to know something about the great Nathan in these last years. My parents spoke very seldom about him. It seemed as if grandfather’s image was surrounded by a mist. I know that he was a convinced mazzinian. Giuseppe Mazzini, great friend of my great grandmother, Sarina Lavi, wife of Meyer Moses Nathan, he had taken Ernest under his wing and treated him like a son. I do not believe the awful things sustained by some that Ernest was an illegitimate son of Mazzini. I have never thought it was true even if he died in Pisa at the house of Janet, sister of Ernest, and Sarina was with him, I know that everyone, like my great- grandmother, adored him because to be a Mazzinian meant to be free”. The word free, on Virginia’s mouth has a profound meaning. The most dramatic parts of her book recount the arrest of her father after he was taken to Regina Coeli and a tentative to free him by a group of partisans to avoid him being deported in Auschwitz. All this while her mother Peggy with Virginia and the other two daughter, Amelia (called May), and Giorgina, escaped from one house to another from a convent in Rome to a village in Abruzzo, not to fall in the hands of the SS. In one of the last pages of her book she describes the sensation of the moment when the Allies arrived in Rome: “the noise and uproar of the crowds in the streets astonished us. Everyone embraced and shouted. We were dumbfounded and I remember that I could not believe that we were free. This word kept creeping back

(digital page 59, original page 2)

and forth in my mind. I kept saying to myself: “I am free, free to walk in the street, free to speak, free to shout, to be noisy, free above all to be and feel free”.

The granddaughter of Ernest likes still to underline how strong the sentiment of Mazzini still is: “to my son Gastone and to my grandchildren Sarah and Edward I keep saying that the most important thing in life is to live accepting everyone without racial and religious prejudices. What has happened to my father, to my mother, to me and to my sisters Amelia and Giorgina, must be a warning, I also tell them that the most important example comes from a far. From Ernest Nathan who arrived in Rome from London hardly speaking Italian; he was retained above his important role as a mayor, the man in the street, a man like many. For him everyone was important, from the road sweepers, the aristocrats, from prostitutes to nuns. A Layman, free, independent, Ernest was hated because of his courage to show them uniquity.(?)

(digital page 60)

THE ANGLO-ITALIAN THAT TURNED THE CAPITAL INTO A MODERN CITY

BY Vittorio Emiliani

A mayor born in London, from a German Jewish father and an Italian Jewish mother, grew up in Milan, got involved in politics in his mother, Sarina Levi’s, birth town of Pesaro. That he, of all people, became mayor of Rome in the early 1900 was not easy to believe or anticipate. Even though he had started, in the opposition, as a republican Mazzinian.

It is true that two circumstantial concomitants helped him: the retirement and the non participation of the administrative vote of 1907 of the moderate clericals and his ascendant to Gran Maestro of the very influential Freemasonry (in the Government and at Court) still well impregnated by the layman’s risorgimental (?) spirit.

But the great amount of work that Ernesto Nathan was able to promote in the services and public business was prepared in Rome in the early ‘900 by a political debate which has never been repeated at that level. The demands that Domenico Orano dedicated to Testaccio by creating the premises for a new populated district. The reflections made in the “Avanti” and other seats of a progressive layman like Meuccio Ruini who developed Rome as a modern capital, also an industrial one (then about 500,000 inhabitants). The search of the economist Giovanni Montemartini, theoretic of the municipalization, created a concrete ground of programs and realisation. The live contribution in the urban sites divided by an institute of Popular Housing (president Giovanni Antonio Vanni) in those times he was the leader of the quality of the building contractors similar to Icp of Milan.

The intense work in the cultural world which they had been involved in for years (and they hardly talked about it), artists like Giacomo Balia (a beautiful portrait by him of Ernesto Nathan exposed in the council Gallery of Modern Art) and Duilio Cambellotti who auctioned their works to finance new initiatives of civilisation in the Agro.

Ernesto Nathan, politician of a cosmopolitan formation, was intelligent enough to act as catalyser of this amount of generous innovative experiences in the cultural world, administrative and social. The committee sustained by the lay-socialist coalition, composed by reformed socialists (the maximalists remained always at a distance, ready to attack later) republicans, radicals, and demo-liberals, were strongly opposed by the Vatican and the nicest expression of the “Osservatore Romano”, dedicated to the layman Nathan remained in the history of Rome. Champion of reforms, capable of using fervid, perhaps unequal political laboratory of which Ivanhoe Bonomi, Giovanni Montemartini, Meuccio Ruini, Tullio Rossi Doha, zio di Manlio, were all part of.