Summary

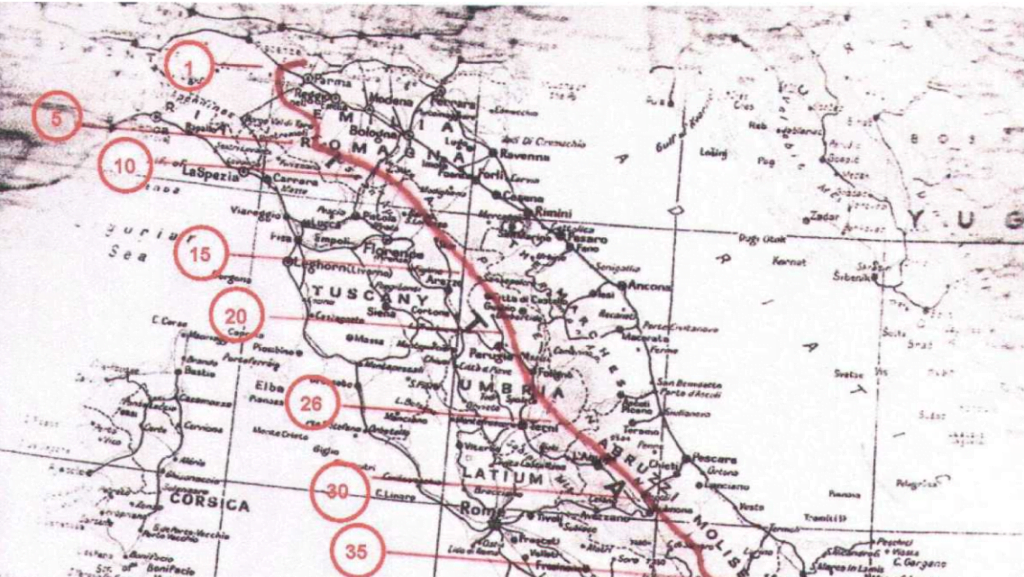

This dramatic and tragic story is written by Charles Gordon Clark, nephew of the subject. Capt. Roger Lawrence, Royal Artillery, was only in North Africa for a short while before being captured during the battle of Sidi Nsir in February 1943. Of the approximately 130 officers and men of 155 Battery at the start of the battle, only nine survived and escaped, the rest being killed, wounded or taken prisoner. After a few days in an Italian PoW camp, they were put on a ship for Naples and once in Italy, Roger spent the first four weeks in hospital before being transferred to PG49 Fontanellato. At the Armistice he and fellow Artillerymen decided to head south and in the four months in which he was on the run, he covered about 400 kilometres.

In January 1944, in very poor, dangerous and freezing conditions in the mountains, Roger was ambushed in a hut in which he was sheltering. His companion George King was recaptured and survived, but Roger was shot by the attacking Fascists and died. He was given a proper funeral and buried locally, but after the war his body was exhumed and buried at the Canadian War Cemetery in Ortona.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[digital page 1]

Captain Roger Fettiplace Lawrence, R.A.

I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: someone has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep them.

J. R. R. Tolkien, ‘The Return of the King’, final chapter.

Roger Fettiplace Lawrence was one of four cousins who died in the Second World War, the second sons of each of the four Eyre Crabbe sisters. They were the daughters of Brigadier General Eyre Crabbe, a veteran of the campaigns in Alexandria in 1882, the Sudan in 1885-6, and the Boer War, and his wife Emily Jameson of the Dublin distilling and banking family. The youngest daughter, Iris, married the eldest son of Sir Trevor and Lady Lawrence of Burford Lodge in Mickleham parish, who succeeded his father as Sir William Lawrence, 3rd baronet. Roger Lawrence, born in 1919, was the youngest of the five children of William and Iris. I am the son of the eldest of these children.

[Photograph of Roger Lawrence]

Roger, the third cousin to die, was the only one to have been before his death a prisoner of war. Like his elder brother Bill, he was at school first at Downsend, near Leatherhead, where I went about ten years after he left, then at Bradfield College. There he was in the school army cadet force, the O.T.C. – Officers’ Training Corps – for four years. Unlike Bill, he went from school to university, to London University in 1938 to study French and German, and again he joined the cadet force, University of London O.T.C. War broke out on September 3rd, 1939, and on the 6th he joined up at South Kensington in the Territorial Army – he was just 20, tall – 6 ft 2½ inches, well built – just over 12½ stone, and medically fit. With his four years in junior and one year in senior O.T.C. and Certificate A Infantry and Artillery, he was immediately posted to an Officer Cadet Training Unit, 121st O.C.T.U. (H.A.C. – Honourable Artillery Company). His choice of regiment was all Royal Artillery (R.A.), Field Artillery preferably, then Medium, then Heavy Artillery. He spent five months at O.C.T.U., and his company commander gave him good, but not outstanding monthly reports – he was “quiet, but pleasantly sound” after the second month with “technical knowledge, on the whole, good”; “gives the appearance of being slightly casual, but is efficient” after the fourth; “well up to average” and “a good sound cadet” in the opinion of the commanding officer after the 5th month. I remember Nanny saying years later that once a soldier Roger determined to make the army his career.

He was commissioned in early February 1940 and posted to the School of Artillery at Larkhill. Four months later he was caught up in the events of the most crucial month in recent British history. Churchill had become Prime Minister in a coalition government on May 9th; we saw above that the evacuation from Dunkirk began on the 26th. By 31st Churchill found when he went to Paris that members of the French government were already talking of an armistice with the Germans. Churchill told them that whatever they did the British would fight on. Even after

[digital page 2]

[Two photographs aligned into the text, with captions]: Roger and Mother {and} Roger and nephew]

Dunkirk had fallen on June 4th, he sent two divisions – all that was left of the British fighting strength – to France to stiffen the Tenth French Army. On June 11th Roger embarked with the 71st Field Regiment R.A. to take part in this second British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France – but he was back in Britain on June 18th. General Alan Brooke, later Lord Alanbrooke, (very distantly related to Roger, as his mother was a Bellingham, the family of Iris Lawrence’s Jameson grandfather’s maternal grandmother!) had assumed command of the improvised formation known as Norman Force on the 13th. He very soon realised that the French campaign was over. The units of Norman Force who had already been in France were retiring westwards from positions on the Seine south of Rouen; then a general retirement of them and of the reinforcements towards Brittany was ordered on 16th June, the day Marshal Pétain, for the French government, asked the Germans for an armistice. Norman Force was then instructed to fall back on Cherbourg and St. Malo from where it was evacuated by 18 June as part of Operation Ariel. Other units left from other Breton ports, and from as far south as Bordeaux. How far from the ports Roger would have gone in the brief time he was in France it’s impossible to say; but he was admitted to hospital on the 20th, and a month later pronounced unfit for service for 4 weeks and given home leave – so something happened to him overseas.

After the return of the BEF the bulk of the army was training in Britain, not fighting overseas; it was two and a half years before Roger went abroad again. In January 1942 Roger was posted to a new Territorial Regiment, 172nd Field Regiment R.A. It was formed at Hastings with personnel largely taken from the 3rd and 5th Coast Defence Regiments R.A., but Roger’s records don’t show that he had been attached to these units. This new Regiment soon joined the Territorial 46th Division and was affiliated to 128th Infantry Brigade which was chiefly made up of three Battalions of the Hampshire Regiment. The 172nd Field Regiment R.A., was made up of three batteries – 153, 154, and 155, each armed with eight 25 pounder field guns. Roger, now promoted captain, was one of the officers of 155 Battery. A photograph captioned “Merstham, 1942”, shows him in command of F Troop, flanked by Lieutenants Heck and Taylor, with 49 other ranks surrounding his noticeably tall figure.

[Photograph with caption] F Troop, Merstham HG.

[Photograph includes Captain Lawrence in the front row]

[digital page 3]

North Africa, battle, and capture

“If your excellency will allow me to express my opinion”, he continued, “we owe today’s success chiefly to the action of that battery and the heroic endurance of Captain Túshin and his company,” and without awaiting a reply, Prince Andrew rose and left the table.

Tolstoy, ‘War and Peace’, Book II, Chapter XXI

Early in 1943 the 172nd Field Regiment was posted to North Africa with 46th Division to join the 1st Army. This had been recently formed after the British and American landings at Algiers, and 46th Division was to help in its push for Tunis and on into Italy. The 1st Army was separate from the 8th Army under General Montgomery, but once in North Africa Roger wrote home that there was this inspiring new British general, quite different from the other senior officers. Roger embarked at Gourock on the Clyde with F Troop on January 3rd on the Jean Jadot, and E Troop joined them at Liverpool. She was a Belgian boat which had managed to escape from Antwerp when the Germans invaded the Netherlands and Belgium in 1940. The master and most of the crew were Belgians, very proud of their ship. The food was good and the voyage almost without incident for the first three weeks, by which time they were in the Mediterranean, approaching their destination of Algiers. On January 20th the troopship, which was in convoy, was hit by a German submarine and sunk in eight minutes; almost all the 300 men on board got off and made for rafts. After two hours most of the men were picked up by a destroyer, HMS Verity, which had a hard time dodging enemy air attacks on the nearly twenty mile journey to port in Algiers. Roger was among a smaller number picked up by a French fishing smack; they joined those from Verity while these were being efficiently re-equipped with all personal equipment except for webbing and small arms. All the Battery’s 25-pounder guns and vehicles were of course lost, with their anti-tank mines, bombs, shells, and 6000 gallons of high-octane petrol.

Lieutenant John Gelly, of E Troop, wrote much later in his memoirs: “Now the roll was called, twenty men were missing, but not one from our Battery. That evening we sat down and talked. What would happen to the Battery; we had lost everything, our guns, trucks, the lot. “Of course, we’ll get re-fitted”, said one. “But in the meantime the rest of the Regiment will go up and have all the fun, if any”, countered Roger….. Liaison between us and the Regiment was soon established and the next day the second-in-command had arrived to take control of the situation. The guns were being got at Bone; we had to concentrate on the vehicles, gun stores, wireless and so forth. It took us just about two weeks to get re-fitted and ready to proceed eastwards to Bone. During the stay in Algiers we made the best of our good fortune to do some sightseeing and visiting.” Most evenings the officers went to a good French restaurant in Baursairaite, a small town south of Algiers. On February 4th the stores were packed onto the new vehicles and they set off in convoy on a journey of 200 miles east through the Atlas Mountains to Bone. The nights were very cold, and wretched looking local inhabitants were glad to scrounge any left-over food. The water wagon plunged over the edge of the road to a drop of several hundred feet.

Roger’s time in North Africa was not to be much longer than his time in France. On about the 9th the re-equipped E and F Troops of 155 Battery took up their position north of the town of Beja, at a place called Hunts Gap. This was on the road to Bizerta, a deep-water port like Tunis, vital for the German defence of north Africa and for the Allied advance to Italy. The other two artillery Batteries, 153 and 154, were deployed to support the main force of 128th Infantry Brigade covering Beja. 155 Battery was supporting the 5th Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment, some twelve miles north-east of Hunts Gap at Sidi Nsir, “City Sneer” as British troops are said to have nicknamed it. It was the narrowest point of the rock-walled valley below the pass beyond which the road dropped down to the Bizerta plain. It was, said one account, “a wild country of stony djebels and barren valleys”. It was not intended to hold Sidi Nsir indefinitely, but the post had

[digital page 4]

been established there as an outpost and patrol base to give warning of any impending enemy attack and to gain time for the forces back down the valley to prepare. A German breakthrough to Beja threatened to drive the First Army back towards Algeria.

John Gelly wrote that “‘F’ Troop had taken the position on the left of the road and about three hundred yards to the front. From the Station the ground rose gradually to about four hundred feet and levelled off for a hundred yards or so and then dropped again. They (‘F’ Troop) placed themselves as best they could, but were unable to site the guns below the crest because of the nature of the ground. This became an important and critical point, as it turned out later.

‘E’ Troop, of which I was Gun Position Officer (GPO), lay on the right of the road in a large field, which had been ploughed the year before and consequently we lived in thick clinging mud from the first day of the rains, but we were able to dig. We made gun pits and slit trenches and my Command Post (CP) was dug six feet below ground level, a fact which later saved my life. And then it rained …………

“I cannot remember a dry spell for more than twenty-four hours. Each morning the men would roll out their wet blankets and lay them out to dry. These were difficult days. We just had to wait for something to happen, and waiting is so difficult, especially when it rains every day and you are fresh and anxious to become veterans, wanting your first spell of active service and very nervous until it actually happens. We did a great deal of ‘registering’, an artillery process of getting the most important areas of the ground in front of the infantry recorded for future engagement, and the Officers changed around from observation post (O.P.) to the guns, and the guns to the O.P. It was arranged the men should go in turn to Beja, for hot baths at the sulphur springs.”

155 Battery first came under fire on February 22nd, but only by about two companies of infantry with mortars, and there were no casualties. The Battery concentrated for the next few days on improving gun pits and trenches, and assured the Divisional Commander when he visited them on the 25th that they thought the “compo” rations issued were more than adequate – all but the biscuits. The Divisional Commander promised that in four days’ time they would be getting freshly baked bread – but as John Gelly said “We never got that bread, for the very next day the Battery fought one of the greatest artillery actions in history, the Battle of Sidi Nsir.”

“On the 26th February 1943 the Germans commenced ‘Operation Ochsenkopf’ in which they launched a determined attack towards Beja, the vital centre for the Allied Communications, with the intention of breaking through the 1st Army lines. The main thrust of this operation was led by an armoured Battle Group including the 10th Panzer Division under the command of Colonel Rudolph Lang together with a number of the new and much vaunted ‘Tiger Tanks’….Just after 6 a.m. on the 26th February, 155 Battery and the 5th Hampshires came under fire from mortars and the first stage in the battle for Beja had begun and was to last nonstop for twelve

[Photograph of an artwork aligned into the text, with caption] BATTLE OF SIDI NSIR

[digital page 5]

hours”. The noise woke John Gelly and at the same time Roger’s Gun Position Officer, Lieutenant Taylor, rang to say that F Troop, being the forward one, were engaging tanks. “Ken Heck at the Battery’s Observation Post… told me there were eight tanks and three of them had a “bloody great gun on it, John: I think it’s a Tiger !!”

We know many details of this epic day’s battle at the close of which Roger was taken prisoner (ironically, if he had time to remember, it was his sister Barbara’s birthday). F Troop was attacked first with heavy mortars and then by the tanks as they advanced down the road. Sergeant Henderson on Number 1 Gun hit three tanks in succession, stopping the attack and blocking the road. The Germans tried to recover the tanks but the battery constantly prevented them by well-placed shells, and they retired. Roger remained at his observation post on the Chechak ridge controlling the guns but at 9.40 a.m. this was captured; he however got away back to the troop.

Throughout the morning the battery was under constant mortar fire, and machine gun fire from aircraft made it very hazardous to get ammunition trucks up to E troop and then on to F troop. A number of these trucks were shot up and left burning. Just before midday the battery also experienced several attacks by eight Messerschmitt aircraft who raked the gun positions with machine gun and cannon fire but did little damage. “Throughout the entire morning”, Gelly remembered, “Raynor, the Battery cook, had worked in his make shift cookhouse completely undeterred by all the activity around him and produced a meal which was greatly appreciated and eagerly devoured by the whole Troop. When we were eventually overrun some hours later and made prisoners, he had the main meal of the day ready to serve in the usual way.”

He continued “Owing to their lack of success during the morning the Germans decided to stand off their tanks and try shooting it out with ‘F’ Troop from ‘hull-down’ positions – that is, putting the tanks behind rising ground until only the turrets with their guns were visible to their enemy (us) thereby making it well-nigh impossible for the tanks to be hit, yet giving them the ability to fire their guns with considerable effect. In this situation ‘F’ Troop were getting the worst of the exchange and their casualties were mounting. While this was going on, the German infantry, which up to now had kept well to the rear were brought forward and being deployed on our right flank. It was about this time when our promised air support arrived; three Hurricanes flew over our position, had a quick look around and then made off. That was the first and last we saw of any of our planes that day.”

Ignoring the risks the Gunners salvaged what they could and manhandled ammunition to the gun positions under heavy fire. They could have withdrawn the guns and engaged the enemy tanks and vehicles from a safer distance, but they placed the protection of the Hampshires first and remained in position so that they could engage the infantry, machine guns and mortars who were closing in on the Hampshire’s positions. The crucial time was between 3 and 6 pm, when the gunners could receive no more ammunition as their supply line had been cut. Around 3 pm F troop telephoned back that tanks were forming up and they were about to be attacked. “That message was the last to come from ‘F’ Troop. The exchange of fire grew less and less until eventually it ceased. We knew their position had been overrun.” The guns were disabled one by one and the positions overrun by the Germans. “One officer, batmen and cooks who could still stand, ran from gun to gun serving each in turn and fought to the last man until ranges had shrunk to ten yards.”

E Troop was now engaging the tanks at under a thousand yards but still could not see them “as they were behind the crest which had protected us from their fire, something ‘F’ Troop had sadly missed and had paid the penalty… The Battery Commander, Major Raworth, also came over

[digital page 6]

from his Command Post and we exchanged a few words about the possibility of holding on until nightfall when we might be able to get the remainder of the Troop away since there was little we could do with four guns to stop the tanks. In any case we would have delayed the advance for at least twenty four hours and a hundred men able to fight again was better than a hundred men dead or prisoners of war.” But at a few minutes past 5 pm Lieutenant Heck at the observation post reported 42 tanks advancing and Gelly knew that the end had come for the whole battery.

“At 5.51 p.m. the last dramatic message reached HQ at Hunts Gap over the wireless “TANKS ARE ON US” followed a few seconds later by the single letter V [for “Victory”] tapped out in Morse code – then silence.” Another writer says, perhaps hyperbolically, “At 1830 hours, standing around their last gun with Bren guns at the hip firing at attacking tanks and infantry, this magnificent Battery died.” It’s said that one officer had radioed earlier: “Self and three men left – Can’t be long now – Cheerio”. This could have been Roger at F Troop, or Gelly at E Troop, though he does not mention it. “Of the nine officers and one hundred and twenty one other ranks on the gun positions or in the Command Posts and Observation Posts at the start of the battle, only nine survived and escaped to join the remainder of the Regiment…. The rest of the Battery were killed, wounded or taken prisoner. Of the Hampshires who fought just as heroically and gallantly alongside the Gunners, two hundred reached safety.” As the Manchester Guardian later said, “The battery might have saved itself many losses, but its first duty was to protect the Hampshire companies.”

Gelly gives an eloquent account of the aftermath of capture: The German major who received the battery’s surrender “summoned John Raworth and the rest of the Battery Officers to join them. Now came the questions: “Where was the other Battery?” asked the German Major. “What other Battery?” we said. “The other Battery which has been firing all day” said the Major. “There was no other Battery”, we replied. They were very surprised and told us so. It appears that the amount of fire power we directed at them throughout the day had convinced them that at least two Batteries, if not a Regiment had been involved. Now we were all paraded, Officers and men and told we were to be marched to the rear of the column of tanks and transported, prior to being taken to the German base at Ferryville or Bizerta…. As we moved, slowly past a continuous line of vehicles and men, the evening rapidly turned to night, and looking back, the flames from the still burning Bren gun carriers shone like beacons against a darkened sky. To my left a burning tank, whose ammunition was still exploding, reminding me very much of a set piece so often seen at firework displays, gave evidence that that the battle had not, after all, been completely one-sided. The German officer escorting us back seemed quite willing to talk in extremely good English and said that he thought the gunners had been very good, and that we would be going to Ferryville by truck immediately we arrived at his Brigade Headquarters. He also explained that he had lived in Nottingham for a number of years prior to the war and thanked us for a very good fight!!! The last gesture was apparently not uncommon among the Afrika Corps; to thank the vanquished for a good fight in much the same way as we at home would congratulate our opponents at Bridge (and modestly suggest we had all the cards). We came across a tank which was going in our direction and some of us cadged a ride for the next half hour or so.” The captured British soldiers spent a rainy night on stony ground, many of them singing defiantly for hours. No food was given at daybreak, except a few scraps by some passing Italian soldiers who did not seem to be taking the war seriously and did not seem to be taken seriously by the Germans. While they were waiting there a dozen British fighter planes dropped two bombs each and the prisoners were lucky not to suffer serious casualties. Eventually they were taken in an assortment of vehicles (including ambulances) to Ferryville. It was not until the afternoon of the next day, after they had been told that they would be handed over to the Italians, that any food was provided – a fifth of a loaf per man, and a tin of sardines. They were then taken to Bizerta

[digital page 7]

where the Italians were quite unprepared for them. The thirty or so prisoners were held under poor conditions for four days and then put on a boat for the twenty hour journey to Naples. British forces captured earlier in Libya were put under Italian charge because Libya was at that time an Italian possession; Tunisia was of course a French possession, but the Germans had presumably got into the way of thinking that the Italians were at least good for looking after Allied POWs.

Brigadier Graham later wrote: “Many, both German and British, thought that the battle was over. But in fact it had scarcely begun. One third of the guns of 172nd Field Regiment had been lost, but a precious 24 hours had been gained and the gallant action of 155th Battery had instilled a healthy measure of caution into the enemy, whose one real chance of success lay in speed”. Another assessment is that “The gallant action and sacrifice of 155 Battery provided the vital delay in the advance of Lang’s Battle Group and thus gave the rest of the Regiment time to prepare and summon further support, so when the next day the German tanks advanced down the narrow road towards Hunts Gap and Beja, 153 and 154 Batteries, supported by three batteries from other Regiments of the Divisional Artillery plus the R.A.F. were ready and waiting for them”. “Then, for ten days, field and medium guns hurled thousands of shells upon them, smashing their tanks and vehicles on the road and mowing down their infantry when they tried to get round over the barren hills. The gunners of 153rd and 154th Batteries took a remorseless revenge for their comrades of 155th who had died at Sidi Nsir”. By March 5th Lang had to retire, with most of his tanks destroyed.

The day after the battle the war correspondent of the Daily Herald met the commanding officer of the 5th Hampshires, “a man full of mirth and vigour, who, with his drooping moustache and his girth, looked like a mixture of Old Bill and a slightly leaner Falstaff. He was tired, dirty, unshaven, his battle-dress muddy and torn after a day’s fighting and a night in the rain, but he was blazing with the glory of the stand made by the gunners of the 155th Field Battery, Royal Artillery, against German tanks down the road from Sidi Nsir to Beja. ‘It was a Victoria Cross act’, he said. That was not the kind of language you usually heard from bluff battalion commanders.” In fact, immediately following the battle this colonel and Brigadier Graham, the Commander of 128 Infantry Brigade, recommended that the performance of 155 Field Battery had been so outstanding that “balloted awards of the Victoria Cross may be made to members of this very gallant Battery”.

On June 8th the details of 155 Battery’s epic fight was made public, “officially described as one of the finest battles in the history of the Royal Regiment”, said the Manchester Guardian in a long and graphic account of the fighting at Sidi Nsir. “The V.C. Battery” was mentioned in the House of Commons, and on the 23rd the action was reported in the Illustrated London News under the heading ‘THE V.C. BATTERY’, accompanied by

[digital page 8]

four photographs of the battlefield and a vivid drawing by the war artist Bryan de Grineau depicting 155 Battery’s last stand. A painting (reproduced above) was later made from this drawing but the Royal Artillery Institution can’t now trace it. The Illustrated London News said the action “might well be described as a modern Thermopylae”. But Victoria Cross awards were never made. One official reason given to the C.O. of 172nd Field Regiment later for the failure of the award to be granted was “too many prisoners”. The son in law of Brigadier Graham said later that the reason the “VC battery” never got the recognition it deserved was possibly due to the fact that “Monty” and he were never in best terms. The battery commander, Major John Raworth, was awarded the M.C., and Roger among others was mentioned in dispatches – but before this had been gazetted on September 23rd he was on the run in Italy.

Fontanellato, and escape

Late on the following morning an Italian bugler sounded three “g’s”, the alarm call which meant that the Germans were on their way to take over the orfanotrofio…

Eric Newby, ‘Love and War in the Apennines’

Roger Lawrence was taken to Italy with the other British prisoners. He must have been wounded at Sidi Nsir, because a week after the battle he was admitted to the military hospital at Caserta, north of Naples, where he stayed for nearly four weeks. He then on March 29th rejoined the other officers from 155 Battery who were having a boring confinement of over two months at a transit camp in Capua. Eventually on May 13th they were transferred to POW camp PG 49 at Fontanellato a few miles north west of Parma in the Lombardy plain. Nearly a quarter of the roughly 500 officers there were like him Gunners, so that it’s not surprising, although disappointing, that the surviving Gunner officer from the camp whom I contacted nearly 70 years later did not remember someone who was only there a comparatively short time.

I have strong memories of my grandmother in Red Cross uniform at a centre in Guildford for sending parcels to POWs – I imagine around this time. Iris had been involved with the British Red Cross for many years, and during the war was chairman of the Surrey Prisoners of War, Wounded, and Missing Relatives Department. During WW2 all the European nations that were fighting one another allowed the Red Cross access to POWs, under the Geneva Conventions drawn up before the war. They were able to visit the camps, check on the health, accommodation, and food of prisoners and complain to the authorities if there were problems.

Fontanellato had been built as an orphanage but had never actually been used as such. It was a large handsome four storey red brick building, with stone dressings, neo-classical details on the projecting wings, and a classical portico rising to the roof level.

[Photograph of Fontanellato]

The prisoners only saw the far more austere back façade. Conditions were generally supposed to have been good for POW camps. Apart from the senior officers, the prisoners were in dormitories of 30 to 35 where they had proper beds, not bunks, and bedside cupboards for their meagre possessions, and there were good washing, cooking, and sanitary facilities. There was a library made up of books sent from Britain and from the British Embassy in the

[digital page 9]

Vatican. The bar on a balcony overlooking the central hall was open twice a day. The hall was used for meetings and games. A multilingual Belgian officer had expert catering abilities, and used the contents of all Red Cross parcels centrally along with the basic ration, so the food was excellent compared with other camps. There were occasional theatrical or musical entertainments and at least one art exhibition, all mounted by the prisoners. Some played seven-a-side rugby or six-a-side soccer. The Italian commandant, Colonello Vicedomini, permitted regular walks into the surrounding countryside. The prisoners were out for a couple of hours, and as well as enjoying the fresh air and the change of scene, wanted to exercise and get fitter, to be prepared for the possibility of escape. A former prisoner wrote: “I particularly enjoyed the walks which Colonello Vicedomini had permitted. A group of 140 at a time lined up in threes, smartly dressed in our uniforms and with our boots shining, and set off early in the morning into the surrounding countryside. We were out for a couple of hours, and as well as enjoying the fresh air and the change of scene, we wanted to exercise and get fitter, to be prepared for the possibility of escape. We took a keen interest in the surrounding area and stored this information for when it might be useful”.

Roger was in there for three and a half months only, because at the beginning of September, Italy pulled out of the war. This was six weeks after the deposition of Mussolini, and if the new Italian government had behaved with enough vigour, Italy might have been free – but they hesitated, and the Germans invaded and placed Italy north of Rome under martial law. News of the armistice signed in Sicily on 3rd September came to Fontanellato on the night of 8th September.

At five to nine next morning everyone was on parade and the Senior British Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Hugo de Burgh, said that some time ago he had received an order from the War Office through the usual channels. It instructed that in the event of an armistice everyone in prison camps should stay put. MI9 had been able to communicate through clandestine radio broadcasts with almost every camp senior British officer during June and July, when it was thought that the allies would sweep rapidly up Italy and arrive soon at the camps. Correctly, Colonel de Burgh said that he believed in view of the German invasion that the order was out of date and did not reflect the true tactical situation. This was very different from what happened at some other camps like the one at Chieti, where all the British prisoners stayed put on the orders of their senior officer, and ended up in Germany. Colonel de Burgh had considered offering the services of his men to help the Italians defend the camp against the Germans, but decided that he did not wish to do anything that might be futile – and embarrass the British Government. What then happened at Fontanellato was unique.

With the connivance of Colonello Vicedomini, who had fought with the British in the first world war, a place was found in the countryside about five miles away where all the prisoners could be hidden. So as John Gelly recalled, “All beds were to be made, lockers cleared and kit laid neatly on the beds. Rations of one tin of meat and biscuits together with a ration of chocolate would be drawn as we might be away for the night. Our haversacks would be packed with anything we might want for a twenty-four hours stay in the country.” Shortly after midday the camp bugler blew 3 Gs and the Italian guards cut gaps in the fence of the exercise field. 600 officers and men marched out, just one hour before the Germans arrived. It’s recorded that “the country lanes were sweltering in the afternoon sun, but no one seemed to mind, they were so happy. Toby Graham recalled: ‘One moment we were prisoners behind wire – the next, free men walking through sunlit vineyards, plucking at the near-ripe grapes.’”

They marched for about two hours into the country north of Fontanellato and though a German Junker plane flew low over them this was not followed up. Towards nightfall they went into a

[digital page 10]

wood beyond a vineyard, where the dry bed of a stream or canal provided shelter under the trees for most of the 600, the remainder staying beneath the vines. Correctly, the senior officers had thought that the Germans would never imagine the escaped soldiers to be so close to the camp. The prisoners remained there overnight, plagued by mosquitoes but heartened by rumours that the British had landed at La Spezia. The next day the Italian officer who had reconnoitred the hiding place brought “several hundred loaves which the local baker had made overnight for the prisoners. With him came a farmer who had milked his entire herd to provide milk for them. He had civilian clothing too.” “Villagers from Fontanellato brought us our own Red Cross parcels. The Germans had arrived only to find us gone and had taken most of our clothes and other things such as the musical instruments, gramophone and sports gear. The parcels left behind were untouched and the villagers just walked into the camp, took the parcels and brought them to us. This was the first of many, many kind acts we were to see them do. Some brought old clothes and it was decided that those who wished could leave and make for the places where it was believed Allied troops were.”

Late on the afternoon of that first day of freedom Colonel de Burgh said that from that night each of the companies into which the prisoners had been divided was on its own. But the decisions what to do were made by far smaller groups. The dozen Royal Engineers decided among themselves; six of the artillery officers, all but one from 155 Battery, decided to stick together. Many of the 600, as with those from other camps, embarked on epic journeys to freedom. Many others, like Major Raworth, were soon recaptured and spent the rest of the war in Germany. There were basically three alternatives: to stay locally and wait till the British or other Allied troops appeared; to head north to the Swiss border; or to head either south west over the Apennines to the Gulf of Genoa, where the allies might land, or follow the line of the main road, the Via Emilia, and the main railway, and south east down the Apennines towards the Eighth Army under Monty. Roger’s group, like Eric Newby who wrote the superb book “Love and War in the Apennines”, and Monty’s stepson, the senior Engineer officer, who crossed the River Sangro in mid-December 1943 and walked into Monty’s camp, to be greeted with “Where the hell have you been?”, decided on the third option. The first option would have imposed great risks on the local population; to go to neutral Switzerland was to risk, if successful, internment until the end of the war, but several, including de Burgh, made it, and had useful months in British legations. The Alps are out of sight from Fontanellato; the Apennine foothills look invitingly near.

By the 20 September 13 of the Fontanellato POWs had been recaptured; more were in the next few days. Two local farmers were sent to a concentration camp in Germany from where they never returned. Colonello Vicedomini was arrested by the furious Germans; he survived the war in a camp in Germany, but had been so badly treated that he died soon afterwards.

The 155 Battery group decided to stay where they were for a further night until they could hear whether there were really were Allied troops in northern Italy. On September 11th, when they had heard that this was untrue, they decided to accept the offer of a woman who turned up about 10 am with more clothes and offered to take them to Fontevivo, further to the south east. The group, by now ten, accepted, and in John Gelly’s words “walked through fields and along irrigation canals, until about half past one. How unfit we were! In the heat of the midday sun, we were continually resting and reached Fontevivo about the same time as some German soldiers, which put the villagers into complete panic. We were pushed into a vineyard to hide until the arrival of our female guide who had gone into the village to find us food and places to stay. She returned within the hour with a farmer who told us that we could not stay in the village as the Germans had arrived! The invasion of Germans turned out to be two soldiers to find a place for the guard,

[digital page 11]

at the railway cross road, to sleep. Four of our party decided to move off, but the rest of us decided to get some food and sit down to discuss what to do next. The food arrived: a loaf of bread, a large piece of cheese and a litre of wine. We sat down on the bank of the canal and ate the food whilst discussing the whole situation. As we ate and talked a man and woman came along, stopped and watched us. Soon they were joined by a man on a bicycle and apparently finding out who we were came over to us and said that he would put two of us up at his farm for a few days. At that, the man and woman came over and made a similar offer. We accepted and paired off, Dennis Brett and myself going with the man and his bicycle, Ken Heck and Roger Lawrence with the woman and George King and a chap named Smith with the other man. Before we left we agreed to meet back at our position at nine o’clock the next day.”

This they did, and as all three pairs were being well looked after they agreed to stay where they were for another 24 hours and meet again. But with Germans around it was the 16th before they decided what to do. “That evening we all agreed on the route to take. We would go down the east coast and hopefully meet the Allies in the region of Ancona some 250 miles away, which we anticipated would take about eighteen days if we averaged fifteen miles a day. From the sparse information we had about our forces we thought they ought to take about three weeks to reach Ancona. Therefore our objective was Ancona. In order to get there we decided to walk north of the railway and road running from Rimini to Parma and beyond, then when near Forli to cross it and make south. We spent the night in Lino’s barn.” (Lino was the prosperous farmer who had taken in Gelly and Brett and was feeding them royally – as well as making them realise that the sympathies of most Italian country folk, actuated as they were by Christian morality, were with the fugitive British.)

On September 17th the small party began their journey south east, leaving shortly after 6 am, and having regretfully refused the sheep’s head which Lino offered them. Guided for a while across fields by Lino on his bicycle, they reached the nearly dry river Taro about 10 am, near Golese. Carrying on east they crossed the first road north from Parma safely, but when they came to the Parma-Mantua road it was thick with German lorries and cars. An elderly Italian helped them cross the road safely one by one. “By late afternoon we reached a river or canal and [had to] walk north until we found a bridge. We must have walked a good three or four miles until we found a bridge, thankfully there were no German sentries. It was during this detour that we realised the difficulties and the extra miles which were in front of us if we kept only to the fields and left the roads alone.” They were very tired when they reached a village about 6 pm, and discovered that there were Germans there. Luckily, making another detour, they ran into three deserters from the Italian army. One, hearing that they were making for Bologna, offered to guide them there which they accepted gratefully. They skirted the German camp near enough to hear their wirelesses and the noise of men working on vehicles, and about 8 pm a scared farmer fed them bread, cheese, and milk, and allowed them to spend the night in his barn – provided they were away at dawn. This they were, and carried on across fields north of Reggio Emilia, being given lunch of pasta and sugo at a farmhouse beset with flies. After that they rested in the sun in a vineyard, and met two disoriented British soldiers who had escaped from another camp. They persuaded them to join them, as they had no idea where they were or where they were heading, except “to join our boys”, so they were now a party of nine. By late afternoon Roger and George King were having trouble with their feet – the party had been forced to walk along a road for about four miles.

“We decided to rest and chose a house lying back a fair distance from the road where we went to ask for some water. We knocked on the door which was opened by the woman of the house. During our conversation with her we discovered that the Germans had been to the property just hours before us and had commandeered their car. It appeared the Germans were moving around

[digital page 12]

the area searching for escaped POW’s so we decided to leave the road and make our way through the nearby wood. Just after five o’clock it was decided to start looking for a place to sleep for the night. As our party had grown to nine, this was much harder than before when it was only seven, which was bad enough. It took us some hours, until it was nearly dark, to find a couple of out buildings which meant we had to split into two groups of four and five. We all slept well and awoke the next morning to the sound of a church bell.” That Sunday they started in high spirits but these evaporated as they seemed to be making little progress. They bathed in a river, and were then given an excellent meal in another house where the owners showed their photograph album and were glad to see the family photos that the fugitives had with them. They then crossed a main road safely but only just missed being caught by a German staff car on the next they came to – fortunately they got into a ditch in time. The locals were panicking at so many Germans around and it took some time for their Italian guide to find a family who would take in Roger and three others; the other four went on until the guide forced a farmer to put them up in a barn. The guide then disappeared – taking John Gelly’s and George King’s packs, and Dennis Heck’s boots. It was a sad end to a day when they had managed to travel twenty miles.

The next morning, September 20th, the party split up, eleven days after leaving Fontanellato. Eight was too unwieldy anyway; and there was a divided preference for which way to go. Roger wanted to cross the railway before Bologna and get into the mountains, Heck and Gelly to stay north of the railway and the Via Emilia. So Roger, George King, Smith, and one of the two soldiers left the other four, intending to move more slowly because of Roger’s and King’s trouble with their feet. Gelly never saw Roger again; he, Ken Heck, and Dennis Brett made it to Allied lines south of the Pescara river in February 1944, after many close shaves and much kindness from contadini.

Death and two burials

“E si divisero il pane che non c’era”

Title of book about the help given by Abruzzesi to escaped POWs

Roger was free for about four months, and, like so many other escaped Allied soldiers, must have been sheltered by many ordinary Italian folk, at great risk to themselves. He covered an impressive distance, something like 400 kilometres from Parma. I presume that all the time he was with George King (P.G. King, his first name was Philip), but sadly King died before survivors were contacted by historians of the POW escapes for details of their wanderings – this was not till 1997. It had never occurred to any of us in Roger’s family to do so. So we do not know their route down the spine of Italy, nor when the four became two. In January 1944 Roger and King were at Goriano Valli, a tiny village in the broad valley of the Aterno about twenty miles south east of the provincial capital of L’Aquila, two thousand feet up in the Apennines below Monte Sirento. Michael Lacey, the POW from Fontanellato whom I got to know, was there in December with a companion begging for food; the second time they went there they “were shooed away. There are Germans in the house.” They had been sheltering in a hut, then an “ice home”, a cave close to nearby Secinaro; it was getting colder and colder.

[digital page 13]

[Photograph with caption] Hut was just below conifers

Silvio Davide was a boy of seventeen in Goriano Valli who nearly seventy years later when Sophy and I visited remembered Roger and his companion perfectly. They were of course in civilian dress, and Roger, tall and dark, spoke Italian well enough to get by. Silvio thought they were there weeks rather than days, so they must have arrived soon after Michael Lacey left. Perhaps they were encouraged to remain because by then there was very severe fighting not far south, on the Sangro river and in the streets of Ortona. Roger and King hid up in a hut which no longer exists on the hillside just south of the village; the hillside was then cultivated but is now covered with brush. They came down for food or it was brought up to them; there was very little to spare. They were given bread soaked in whey left over from making the cheese.

In mid-January the villagers became aware of a woman passing herself off as a spy on behalf of the British, trying to get news of escaped POWs and in fact betraying them to the Fascists. On the night of the 14th the two officers were advised to leave at first light. They rushed hastily out of the village and up to the hut, not stopping to put on their shoes. There was snow on the ground and their tracks were conspicuous. In the early morning of the 15th they were surprised in the hut. George King froze, was recaptured, and survived to tell the tale. Roger made a movement, and was shot four or five times. Silvio heard the shots from his family’s house, the nearest to the hut. Roger collapsed and after King had been taken off he died, “vilmente assassinato dagli sgherri tedeschi” as the parish priest wrote some months later to the Red Cross – “vilely murdered by the German thugs”. Why did the priest write that the assassins were German when he must have known that they were Italians? Perhaps because when he wrote, the following November, he realised that he needed to remain the priest of all his parishioners, partisans, ex-Fascists, ordinary contadini. A British private soldier, passing through the village some weeks later, was told that Roger had been killed by Fascists.

[Photograph presumably of S. Justa parish church]

There was apparently only one German soldier there, who reluctantly gave permission to the priest, Matthias Trippetilli, for Roger to have a proper funeral. His body had been brought down from the hut strapped onto a ladder, four men carrying and four more relieving them. The parish church of S. Justa, virgin and martyr, is on top of a little hill opposite the hut and about half a mile away. The body was blessed at the west door, the villagers being kept back by the German soldier, then carried in for the funeral rites. It was then loaded onto a camionetto and driven to be buried in the parish cemetery of San Georgio on the small hill just to the north. Many people came to his funeral, for his death was “un grave lutto per la popolazione di questa frazione” – “a great grief to the people of this neighbourhood”. It was that statement of the parish priest that first made me

[digital page 14]

think that he might have been in the area for a while. There was no coffin, but a board was placed over him so that the earth should not fall on his face. Over the next few months his “povera tomba” in the communal part of the cemetery was often visited by the parishioners visiting the cemetery, and whenever there was a funeral they said prayers at his grave “intendendo così di rappresentare i parenti lontani” – “with the intention of doing that on behalf of his distant family”. Silvio’s wife and cousin confirmed this. Most of the cemetery, at the back of a now disused convent, is filled with small edifices, each the tomb of one family; there is just this small grass covered area for strangers. Movingly, just by where Roger lay there happen to be small plants of iris, daisy, violet – the names of Roger’s mother and aunts. To my relief, there were no reprisals against the villagers for sheltering Britons.

[photograph aligned to the right of the text with caption]: Silvio Davide by the site of Roger’s first grave.

One of my strongest war memories, and the most painful, is of my mother rushing upstairs in tears when the news of his death reached us. This was probably towards the end of February, because Lieut. P. G. King gave the details to Colonel Kenyon, the senior British officer in Oflag VIII F, a POW camp in Germany, and Col. Kenyon sent them to the International Red Cross in Geneva on the 11th February.

[Photograph of grave stones aligned to the left of the text]

After the war ended in May 1945, Roger’s body was exhumed and sent to Ancona on the coast. It was then buried in the Moro River Canadian War Cemetery in the Commune of Ortona, in the province of Chieti. It’s near the Adriatic coast of Italy, still in Abruzzo. My mother and grandmother went out there to see his grave after the memorials were all in place. Beyond the grave are olives and pines, then the sea. Turning round you see the mountains, snow covered when Sophy and I were there. John Gelly went with Ken Heck to the Moro River in 1952 and took a picture of Roger’s grave, but he never spoke to his family of the details of Roger’s death as, his son told me, what he had heard from George King hurt him too much.

Many years after Roger’s death I had a tree, a Scots pine, planted in his memory in the National Memorial Arboretum, 150 acres of wooded parkland within the new National Forest in Staffordshire. Later again I started contributing to a charity, the Monte San Martino Trust, which commemorates the help given by Italians to the escaped prisoners of war by giving their descendants a chance to study in Britain. Thalia and I went to Fontanellato in September 2013 as the Trust and the townsfolk wanted to commemorate this unique episode. We were given a wonderful and moving welcome.

[Photograph aligned to the right of the text of a Scott’s pine]

A scroll was given to my grandmother by the parish of Mickleham and Westhumble – I presume a local version of one shared by parishes across the country. On it, in beautiful calligraphy, “The residents of the Parish hereby record their gratitude for the services rendered by Capt. R. Lawrence R.A. to King and Country, their pride in his achievements and their sorrow that he was not spared to return to his home. By their deeds and self-sacrifice he and his gallant comrades have proved themselves worthy sons and daughters of this ancient parish.” Roger’s name is on the grave in Mickleham churchyard where his parents and grandparents are buried, the grave originally made for his great grandparents John and Elizabeth Matthew. There is a memorial in the village of Sidi Nsir to the battle on February 26, 1943.

[digital page 15]

SOURCES:

By Charles Gordon Clark

I got Roger’s army record from the Army Personnel Centre records in Glasgow. Details of his death came originally from my memory of papers my mother had which I gave after her death to my uncle Bill – they may still be at The Knoll, but can’t at present be found (they may have been in a safe which was stolen). Eventually I got from the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva their full file on his history as a POW and his death and burial.

The memoirs of John Gelly came to me from his son as a result of his reading what I wrote on the Monte San Martino website about my search for Roger. They have added much valuable detail to the story.

Other details of his battery come from on-line sources, and from A.B. Austin (the war correspondent of the Daily Herald), ‘Birth of an Army’, published later in 1943. ‘Crucible of power: the fight for Tunisia, 1942-1943’ Kenneth Macksey, has more details.

Fontanellato has had much written about it. I have used Ian English, ‘Home by Christmas’?, Eric Newby, ‘Love and War in the Apennines’, Tom Carver, ‘Where the hell have you been?’, Laing and Clarke’s articles in the Birmingham Post, available on line. The Gunner POW I corresponded with and then met is Michael Lacey of Haslemere.

Sophy and I went to Goriano Valli at the end of March 2012. We are deeply grateful to the Segola/Liberato family, and to their cousin Silvio Davide. Thalia and I went to Fontanellato in September 2013, for the 70th anniversary of the escape.

The scroll is now in the Dorking museum.

POSTSCRIPT

In 2013, Charles Gordon Clark learned valuable details about his uncle’s experiences during the fighting at Sidi Nsir and thereafter through the memoirs of Lt John Gelly, a brother officer of Roger Lawrence in the 155th Bty/172nd Field Regiment. Lt Gelly was also imprisoned at Fontanellato. The new information enabled Charles to write the following detailed account of the journey made by Lt Gelly, Roger Lawrence and companions after the escape from Fontanellato at the Armistice in early September 1943.

The passage includes extensive quotations from Lt Gelly’s memoirs. We are grateful to his son, John Gelly, who got in touch with Charles Gordon Clark after reading the original account above, for permitting us to publish them.

Late on the afternoon of that first day of freedom, September 9th, Colonel Hugo de Burgh, the senior British officer at Fontanellato PoW camp, said that from that night each of the companies

[digital page 16]

into which the prisoners had been divided was on its own. But the decisions as to what to do were made by far smaller groups. The dozen Royal Engineers decided among themselves: six of the artillery officers, all but one from 155 Battery, made the choice to stick together.

On the 10th, the 155 Battery group decided to stay where they were for a further night until they could hear whether there were really were Allied troops in northern Italy. On September 11th, when they had heard that this was untrue, they decided to accept the offer of a woman who turned up about 10 am with more clothes and offered to take them to Fontevivo, further to the south-east.

The group, by now ten, accepted, and in John Gelly’s words, “walked through fields and along irrigation canals, until about half past one. How unfit we were! In the heat of the midday sun, we were continually resting and reached Fontevivo about the same time as some German soldiers, which put the villagers into complete panic.

“We were pushed into a vineyard to hide until the arrival of our female guide who had gone into the village to find us food and places to stay. She returned within the hour with a farmer who told us that we could not stay in the village as the Germans had arrived! The invasion of Germans turned out to be two soldiers to find a place for the guard, at the railway cross road, to sleep. Four of our party decided to move off, but the rest of us decided to get some food and sit down to discuss what to do next. The food arrived: a loaf of bread, a large piece of cheese and a litre of wine. We sat down on the bank of the canal and ate the food whilst discussing the whole situation.

“As we ate and talked, a man and woman came along, stopped and watched us. Soon they were joined by a man on a bicycle and apparently finding out who we were came over to us and said that he would put two of us up at his farm for a few days. At that, the man and woman came over and made a similar offer. We accepted and paired off, Dennis Brett and myself going with the man and his bicycle, Ken Heck and Roger Lawrence with the woman, and George King and a chap named Smith with the other man. Before we left we agreed to meet back at our position at nine o’clock the next day.”

This they did, and as all three pairs were being well looked after they agreed to stay where they were for another 24 hours and meet again. But with Germans around, it was the 16th before they decided what to do. “That evening we all agreed on the route to take. We would go down the east coast and hopefully meet the Allies in the region of Ancona some 250 miles away, which we anticipated would take about eighteen days if we averaged fifteen miles a day. From the sparse information we had about our forces we thought they ought to take about three weeks to reach Ancona. Therefore our objective was Ancona.

In order to get there we decided to walk north of the railway and road running from Rimini to Parma and beyond, then when near Forli to cross it and make south. We spent the night in Lino’s barn.” (Lino was the prosperous farmer who had taken in Gelly and Brett and was feeding them royally – as well as making them realise that the sympathies of most Italian country folk, actuated as they were by Christian morality, were with the fugitive British.)

On September 17th, the small party began their journey south-east, leaving shortly after 6 am, and having regretfully refused the sheep’s head that Lino offered them. Guided for a while across fields by Lino on his bicycle, they reached the nearly dry river Taro about 10 am, near Golese. Carrying on east they crossed the first road north from Parma safely, but when they came to the Parma-Mantua road it was thick with German lorries and cars. An elderly Italian helped them cross the road safely one by one.

“By late afternoon we reached a river or canal and [had to] walk north until we found a bridge. We must have walked a good three or four miles until we found a bridge, thankfully there were no German sentries. It was during this detour that we realised the difficulties and the extra miles which were in front of us if we kept only to the fields and left the roads alone.”

[digital page 17]

They were very tired when they reached a village about 6 pm, and discovered that there were Germans there. Luckily, making another detour, they ran into three deserters from the Italian army. One, hearing that they were making for Bologna, offered to guide them there which they accepted gratefully. They skirted the German camp near enough to hear their wirelesses and the noise of men working on vehicles, and about 8 pm a scared farmer fed them bread, cheese, and milk, and allowed them to spend the night in his barn – provided they were away at dawn. This they were, and carried on across fields north of Reggio Emilia, being given lunch of pasta and sugo at a farmhouse beset with flies.

After that they rested in the sun in a vineyard, and met two disoriented British soldiers who had escaped from another camp. They persuaded them to join them, as they had no idea where they were or where they were heading, except “to join our boys”, so they were now a party of nine. By late afternoon, Roger and George King were having trouble with their feet – the party had been forced to walk along a road for about four miles.

“We decided to rest and chose a house lying back a fair distance from the road where we went to ask for some water. We knocked on the door which was opened by the woman of the house. During our conversation with her we discovered that the Germans had been to the property just hours before us and had commandeered their car. It appeared the Germans were moving around the area searching for escaped PoWs so we decided to leave the road and make our way through the nearby wood.

“Just after five o’clock it was decided to start looking for a place to sleep for the night. As our party had grown to nine, this was much harder than before when it was only seven, which was bad enough. It took us some hours, until it was nearly dark, to find a couple of out buildings which meant we had to split into two groups of four and five. We all slept well and awoke the next morning to the sound of a church bell.”

That Sunday they started in high spirits but these evaporated as they seemed to be making little progress. They bathed in a river, and were then given an excellent meal in another house where the owners showed their photograph album and were glad to see the family photos that the fugitives had with them. They then crossed a main road safely but only just missed being caught by a German staff car on the next they came to – fortunately they got into a ditch in time. The locals were panicking at so many Germans around and it took some time for their Italian guide to find a family who would take in Roger and three others; the other four went on until the guide forced a farmer to put them up in a barn. The guide then disappeared – taking John Gelly’s and George King’s packs, and Dennis Heck’s boots. It was a sad end to a day when they had managed to travel twenty miles.

The next morning, September 20th, the party split up, eleven days after leaving Fontanellato. Eight was too unwieldy anyway; and there was a divided preference for which way to go. Roger wanted to cross the railway before Bologna and get into the mountains, Heck and Gelly to stay north of the railway and the Via Emilia. So Roger, George King, Smith, and one of the two soldiers left the other four, intending to move more slowly because of Roger’s and King’s trouble with their feet. Gelly never saw Roger again; he, Ken Heck, and Dennis Brett made it to Allied lines south of the Pescara river in February 1944, after many close shaves and much kindness from contadini.

Charles Gordon Clark