Summary of Norman Dean

An extract from a longer biography, this story focusses on Norman Dean’s capture by the Germans in North Africa through to the end of his career as a soldier in the 1950s. He served in the Royal Artillery and escaped from PG53 Sforzacosta. His tale is unusual as he describes good treatment by the Germans, and his life in Italy feeling that he had little to fear from them. He stayed in the Massa Fermana area until 1944 and provides very detailed descriptions of life at the time with an Italian farming family named Forte. His text is interspersed with his own drawings and diagrams. Please contact the Monte San Martino Trust if you wish to read the full biography.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital page 1]

[Title] It Was All an Adventure

[Photograph of Norman Dean as a young man]

G.N.J. Dean

[Digital page 2]

Introduction

[Digital page 3]

At the time when Grandad was becoming more involved with his wartime companions in his Artillery Regiment’s reunions, I was finishing my education and I was presented with an opportunity to reflect. In doing so I decided that Grandad would have a great many more tales and memories than I. So, in the summer of 2000, Grandad and I set about collating some of his wartime adventures. Having done this I decided that it would be fascinating to have a record, for us grandchildren in particular, of what it was like growing up in the country almost eighty years ago. Most of what I know of these times, I have learned from history books, so what better way to record these ‘historical’ events than from my Grandad who lived through these years and experienced them first hand!

I know that Grandad has had reservations about this project, fearing that he has had an ‘ordinary’ life with little to tell. I will leave that to the readers to decide, but by the time he was 24, Grandad had not only worked for ten years but had also been posted to Africa to fight the Nazis and had even got married! I on the other hand, had only just finished my education! Completing this work has taken far longer than either of us imagined, but once started, I felt that it was important to have a complete record of Grandad’s life as possible. I hope you gain as much pleasure from reading this remarkable story as I have had in researching and writing it. Throughout my education I have written many stories and essays, but this is by far the greatest piece I have ever written and best of all, it is all true and from my Grandad.

This book contains all of the ingredients of a classic tale; action, adventure, love, romance, heroism, honour, pride, modesty, humour, loyalty, devotion, respect and kindness. Yet it is no fictional tale, it is my Grandad’s life story.

*[Editor’s note] Only excerpts from this life story that relate to Italy during World War Two have been published on this website. If you wish to read the whole story please contact the Monte San Martino Trust via the website.

[Digital page 4]

No matter what the hardships or difficulties that Grandad has been presented with, he has never compromised his beliefs and morals and has remained a truly special person and someone we should all aspire to be like. I hope that when I reach my years of reflection, I will be able to look back on a life half as interesting as that of Grandad’s and one that he would be proud of.

I give you the memoirs of my Grandad; George Norman Ronald Dean.

Peter John Norris

Autumn 2001

[With the signatures of G.N.R.Dean and Peter Norris]

[Image of the family tree of Geroge Dean, with first names only and no dates]

[Digital page 5 left]

[Chapter Title] Capture

Bernie Applebaum, who was an O.P. signaller, suffered an injury and was returned to base. In his place, I was sent to man the radio set in the O.P.. This was on a slight hill overlooking Goubellat Plain, which was by no means a flat plain, but you could see for a long distance in the undulating countryside. We were in an advance position from our troops at this O.P.. I was up there with infantrymen from the East Surrey Regiment, who were there to protect the O .P. and I think I had only been there one night before the action started. The day before I was captured was the first time that I had eaten ordinary food, perhaps say boiled potatoes and fresh meat, rather than the compo rations, not that I minded the compo rations. We were given bread to eat, which we had to cut the crust and mildew off and just eat the inside.

I was in a bit of a dugout with the wireless set, and I believe that I had some of my outer clothes off in ‘bed’, which of course, was not the thing to do! It was as much as I could do to get dressed and to get out, I did not even have time to take my ‘Tommy Gun’ with me. I do not think I did anything to damage or dismantle the radio set, which was undoubtedly against the rules. I had to go across a bit of an open space and up over a bank to get to a little bit of shelter where the infantry were. I had to depend on being told what to do and where to go by the infantrymen, as I was out of sight up to then. What I remember quite vividly was the small arms fire going over me, as I was making my way to comparative safety, and looking up and picturing noughts and crosses with all the bullets flying past. I got back over to the other side, where the infantrymen were a little downhill of me, to my left, keeping their heads down. One young

[Digital page 5 right]

fella, a cockney, got up in the trench ready to fire, “you b*****ds” he was shouting to the Jerries, “you killed my mother and father in the blitz, now you’re going to get it”. Then before I even saw him fire his gun, his tin hat went spinning off and rolled down the hill behind him and steam came out of his head. That was the only time I can remember watching, in a sense in cold blood and close up, someone being killed. By this time, Jerry was commanding the hill and had us completely pinned down. In command of the O.P. was an officer, Lieutenant Webster, who was not well known to me. He was a short distance away from me and slightly higher up the hill. I became aware of him Lt. Webster moving across above, in their full view. He shouted to me “come with me Dean”. With that he was shot dead.

Shortly afterwards, someone must have shown the ‘white flag’, which meant that we were free to come out of our trenches or whatever we were sheltering in. We went forward to the Jerries who were all amongst us by this time. We went there in comparative calm, without being shelled by either side. Bernie later told my mother that he had seen me being marched away smiling, from his position back to the rear. The rest of my battery was therefore very close to us when we were captured. We were marched away in three columns, as we would march normally ourselves. I do not know how many of us there were, but I would guess there was twenty or more of us in each column, with myself being the only gunner. The Jerries were good to us really, quite friendly. I recall one of them who was marching alongside us, had no end of gear he was carrying so he off-loaded one of these items to our column. It was very heavy, perhaps a machine-gun tripod. It went to the man in the front who passed it back so we all had a turn carrying it. When it came to me, it was as much as I wanted to carry on its own and that was only a small part of what he was

[Digital page 6 left]

carrying! When we stopped somewhere and they gave us a drink, what I drank from his water bottle was wine. No doubt this came from the French who had vineyards in Tunisia and Algeria. At best we would only have water in our bottles! I think they probably looked after themselves a bit better than us. I do not think we walked very far before being put on some form of transport.

When we got back to where there was a German unit I know one thing we did, which we should have refused, was to off-load some ammunition into a store for them. I remember there they did not have a lot of food to give us, but they did give us some cheese and did the best they could to look after us in the circumstances. None of us could speak a foreign language, but some of them could speak English and they said to us “why didn’t you come in the war with us and defeat the Russian beasts?”. Then they would say ”you’re lucky, you’re going back now” and they would imply that we would be going to safety and would be able to play football. That is what they had in mind and thus they envied us being prisoners.

I knew my parents would be informed of my circumstances, though I had no evidence to confirm this. Eventually, once we were settled in the P.o.W camps, I wrote to them, but there was no way that they could have replied. As was the case when I was in action, our whereabouts was always kept ‘hush-hush’. There were two letters sent to my mother to inform her of my capture, the first was written by my friend, Bernie Applebaum. He was perhaps more of a friend to me than anyone else in our Regiment even though he was never in my actual Training Regiment at Aberystwyth, which was due to the fact that he had been in the army a few years before me. The second letter was sent by Arthur Long, which is pictured below. This was written in pencil, as were all of our letters,

[Digital page 6 right]

although the Commanding Officer’s note to me was in ink. Fountain pens would have been impracticable and besides, who would carry bottles of ink around, since biros had not been invented then? Even to this day, I am unsure how anyone could have been so close to me to notice me smiling, yet not be involved in the action themselves. We had no prior arrangement to let anyone’s family know in this way. The authorities did contact our families eventually and a copy of such a letter is shown after the letter below, which informed my parents that I would only continue to receive my pay for six months.

[Image of Appendix B letter informing the author’s parents of his ‘missing’ status]

[Digital page 7 left]

[Image with caption] The official letter informing my parents of my capture.

[Digital page 7 right]

[Image with caption] Letter written by a fellow Gunner [Arthur Louf] who was aware of my capture]

[Digital page 8 left]

Eventually we ended up in Tunis and were put in a school where the classrooms were used as dormitories. Using some French Francs we had, a German soldier would come round like a canteen assistant, and ask us for our orders. He used to go out into the town and buy everything we had ordered and brought it all back, with our change, as good as gold. I am not sure what we would have bought, but I used to have a cake like a doughnut. I still have some Algerian money, which we must have intended using at some point on our travels, as shown below. In the compound they used what we had in the old days, a wash boiler, with a wood fire underneath it, which heated up stew of some sorts. We would go with our mess tins and help ourselves. I remember asking someone what the meat content of the stew was and he told me it was a donkey’s head! Perhaps I should not have asked.

[Image of an Algerian five francs note]

[Digital page 8 right]

[Image of the back of the same Algerian five francs note]

From there we were sent to another compound, which was this time, run by the Italians. I think it was an old factory and certainly we had no access to the outside world, with only limited scope for actually seeing daylight. Whatever we had the Italians wanted to deprive us of it. They were not at all kind towards us, as the Germans had been. I do not think the Italians there did anything for us at all and I cannot think what they gave us for food. I do recall the enterprise of some of our chaps for they used to make packs of cards out of empty packets of cigarettes and would sit there and play. I am not religious, but I did envy one chap there who had a bible, as at least he had something to read, which would last a long time. I did not play cards and I do not think I had anything in particular to occupy my time, not that it was ever a problem. It was there that I was most conscious of not having my greatcoat, whilst many others had theirs. It did not matter in the end though as I never really had the need of it, for it just harboured fleas when we were in the P.o.W. camps. By this time

[Digital page 9 left]

there was a real mixture of fellow P.o.W.s and not just those who had been captured with me, although I was never aware of anybody from my unit ever again.

Eventually we sailed after eleven days in Tunis, to our destination in Italy. I was never anymore fearful than I was then, for we were down below, well under decks, which is not the place to be in the event of an attack. One of our greatest threats came from the possibility of an attack by Allied aircraft. For food we had what was like a hard dog’s biscuit, which we mixed with drinking water and some form of meat in small tins. This was our daily ration and I never went to the toilet the whole time I was on board the boat, save for spending a penny! For this we did not have to go up on to the top deck. Where we were down below, there were boards spaced apart inside the hull to protect the cargo if it moved and through a space, the pennies were spent. Down it would go, but to where, I never knew! I suppose it must have gone into the bilges somewhere, to be pumped out with other water. I used to sit with a much older chap from London called A.G. Joseph who was a film critic for the Daily Mail before the war. We would pass the time by naming County Championship cricket grounds; the teams and players. We would try to name the batsmen and bowlers of each team and do a similar thing for football clubs. He was a man to feel sorry for because of his age, you cannot adapt too well, being so much older. I think you take things as they come better as a youngster. That was about it as far as life on board that particular boat was concerned.

[Digital page 9 right]

[Chapter title] Prisoner of War Camps

We docked in Naples without having experienced any great drama on the crossing and were held in Campo di Concentramento P.G:66 (Prigionierei di Guerra, or Prisoner of War) with other Prisoners of War. This camp afforded us a quick and good introduction to the thousands of fleas there. Not only was it very hot and dusty, but we could not see a square inch of ground that did not have a flea on it! In the wooden barracks there were double bunks and people would catch the fleas they found in their greatcoats and would count hundreds of them. Then in the afternoon they would do the same again and catch another hundred or so. I cannot think that we had any blankets or bedding there which was probably just as well given the fleas! I do not think I bothered doing anything like that, for you would always be fighting against the odds. The nicer part of that camp was that once we had arrived there, existing P.o.Ws welcomed us and put on a little concert party. I remember them singing a particular song, but I can only recall part of the first verse:

“In Campo di Concentramento P.G.66, it’s seldom you’ll ever see a frown.

There’s English, there’s Irish there’s good old Welshmen too.

And the Scotsmen who will never let you down.”

That was holiday camp style singing and it was really lovely to have that little bit of entertainment. There were other organised events there as well, such as lectures by knowledgeable people. One of our seniors there talked to us about soya beans, which can be lectured about for some length! As far as he was concerned, you could do all sorts with them, including building roads, and they

[Digital page 10 left]

could be eaten. Fifty years on, everyone has knowledge of them! We would have had lectures on other subjects as well, but I cannot say on what now. We also had boxing matches, but I do not know who would have been fit enough to put up much of a show, except for new arrivals So there was something there, which was good enough for the rest of us by way of self-entertainment. We also had a lot of mixed races and I think the Arabs had their own huts and areas that they kept to. We were riot barred from their area, and I remember walking through there once and seeing something which was a bit of an eye opener, in that they all had shaved heads. The chap who did the shaving used an ordinary two-sided razor blade; very deft. Also in this area, I was amazed to see the food they put into mess tins, presumably to be heated up. One example was tinned rice pudding mixed together with pilchards! The ingredients would have come from the Red Cross Parcels, which we were all so grateful to receive. Their meals were quite off-putting to us, but then all of our food gets mixed up once inside of us I suppose!

Outside the perimeter of the camp was a German Panzer unit. We were able to go right up to the fence, or at least up to the trip wire which was on our side of the fence. Sometimes the Germans came up to the fences and threw bread rolls over to us. Although the Italians tried to stop them, they were simply ignored by the Germans. The Italians certainly knew their place! Sometimes a couple of women would walk up close to the perimeter and what was said and requested to them was no man’s business and is not for repeating here! I do not know how many there were in that camp but it was obviously quite a lot. One interesting event that happened there was when the Italian guards were issued with ‘socks’. They were given. a square piece of open weave material like a dishcloth, which they put over the top of their boots and simply pushed their

[Digital page 10 right]

feet down inside. That was their issue of socks and the rest of their equipment was equally poor. What amused me were their names for I had never been used to foreign names, such as Andreilotti or some long peculiar name such as that. Nowadays, with all of the famous foreigners we hear of, particularly in the world of sport, things are rather different and not so out of the ordinary anymore.

There never seemed to be anybody depressed in the camps, no real bother or antagonism between anyone and generally the mood was quite good. I think it was at that time and given the circumstances with the small vermin, I thought about having my hair shaved off. However, then there was the possibility that we all might be ordered to have it shaved off. That then finished it for me and there was no way I was going to have it cut off until I could delay it any longer! In the end I never had my head shaved, from start to finish. I think myself that there was a feeling of less intensified danger being a P.o.W.. My father had been a P.o.W in the First World War over in Germany and they had to scrounge around the German’s dustbins and boil potato peelings and nettles to keep themselves alive. The Geneva Convention was not as strong then and we had no fear on that score. We were never going to be living a life of luxury, but we did have food to eat. What was supplied by our hosts, little of which I remember, was not very luxurious or plentiful, but thankfully was augmented by our weekly parcels from the Red Cross.

We were moved by train to another camp away from Naples, up to more of the ‘calf of Italy, to Campo di Concentramento P.G.53. The first camp was quite big and I cannot remember how the Italians decided who should be moved, but we could not go until space became available elsewhere. The new camp was

[Digital page 11 left]

different altogether for it had solid walls, perhaps it was an old factory, but it was certainly more permanent. We had a bath/shower blocks and washbasins which must have been built on in this area. The land around it was big enough for us to play football and cricket on. To one side was another block of smaller buildings where there were our officers. They were there for our benefit, morally and physically, as they were Captains in the main, Padres or Medical Officers. This meant we could have gone on ‘sick parades’, not that I can remember ever needing the services of either of them. They catered for all sorts, but I think there were only British men there, no Arabs or anyone like that at this camp. We were all in treble bunks, which were very tightly spaced to one another, the top one not being as high as the bunks you can buy today for children. We had another smaller building separate from us, which was used as a cookhouse.

In the Red Cross Parcels, possibly only in the Scottish ones, there would be oats so we were able to make porridge for breakfast, though only if we had handed a tin into the cookhouse, which was not very often. Of the camp food which I enjoyed the most, was just plain rice, onions and pea flour all mixed together. Pea flour was always a gift of the Argentine Red Cross and the onions and possibly the rice were home grown. Pea flour was anything but sweet, though it had a nice taste, as did the rice, whilst onions were not in any way objectionable. This ‘stew’ was really lovely and I could have lived on it forever. If the Italians, in their generosity, added a bit of meat and perhaps a bit of cheese, in my way of thinking it spoilt it, even though it would have been more nutritious for me. That was a pleasant reminder of food in that camp. We also had little, hard, bread rolls that were lightly raised, but I do not know

[Digital page 11 right]

about having anything to spread on them except we occasionally received some butter in a parcel.

Though the camp had a library, it was of little use as there were so few books in it; mostly biographies and historical ones. There was a private library that could be joined by buying a book and giving it to the library. Eager·to join, I saw an advert on a notice board asking for a tin of egg flakes in exchange for a book. As luck would have it, I had a tin of egg flakes in

one of my Red Cross Parcels, so I went and bought my book and from then on I was never without; in fact I ended up reading one book a day! Most of them were Penguin paperbacks and I would go and sit with my back up against a wall in the sunshine, day after day, for there was never any problem with the weather over there. As it happened, the advert on the notice board for the book was next to a clock on the wall made by another prisoner, entirely from empty tins, which not only worked, but it also told the correct time. It was a pendulum clock, weighted by tins from the Red Cross Parcels filled with sand. The Commandant of the camp wanted the clock for himself, but a prisoner destroyed it before leaving the camp to stop the Italians getting hold of it. I have a photo of it taken from a British newspaper printed after the war.

[Photograph of the clock]

A lot of the others stayed in on their bunks or walked and hung about, whilst some had baths and washed and dried their clothes. Though there were no fleas

[Digital page 12 left]

in this camp, there were lice, so clothes had to be deloused. The lice would be picked off the item of clothing, which was hung up to dry on a line. A lit cigarette would then be run down the seams to kill off the lice and their eggs. When we went back to pick the dried clothing in, it would still be crawling with lice! But that is what we had to contend with; there was no-way could we get rid of them. I used to have them mainly around the inside of my belt, as I think they could attack the flesh better under the pressure. Even to this day I still have the scars of being fed on! As well as the lice to contend with, there were bugs in the beds. I saw other men dismantle their bunks and pass the bits through flames from fires started by burning cardboard from the Red Cross Parcels. I thought those who did this may have originated from ‘slummy’ places themselves perhaps London, where they had experienced bugs in their ordinary life. I had never experienced anything like them in my life, but once I had, it was enough to put me right off! Some men were very fastidious and smart all of the time and although they could not iron their clothes, they put them under their mattress to press them instead!

Others played football in leagues, which involved matches of short duration, due to the heat. Those leagues would be going all day long, though they stopped for meals, which were at a set time, since they came from the cookhouse. So badly worn was the surface of the football pitch, that it was just grit and gravel. The footballs wore out so quickly that a ball would only last for one day! The Red Cross supplied the footballs but I cannot remember how they arrived, whether they were inflated or not! When I think back we had a lot to thank the Red Cross for. No doubt there had been international football matches played previously, such as between any of our British countries, but on one occasion in the camp, England faced a mixed team selected from the

[Digital page 12 right]

other countries, who became known as ‘The Rest’…There were plenty of men who enjoyed a game of football and there was also a sprinkling throughout the forces of well-known sportsmen who had played professionally for our teams prior to the outbreak of the war, including the odd international player. This game was a pleasure to watch and since this game coincided with the Armistice, it was one match that I watched and certainly enjoyed. In fact, it was the only time England won this particular fixture. the result 1-0 to England.

The Red Cross Parcels were from different towns in the British Isles and would have their town of origin marked on them. The best and most favoured parcels were the Scottish ones though I never had much feeling for the ones from the North East for some reason or another. I think perhaps it was due to the Tyne Brand meat factory and I never liked their products. The luncheon meat from there was disappointing and in no way comparable to the meat products such as the imported American Spam. Everything as always in tins; including cheese! We would have had up to twenty different items in each cardboard parcel, which would have been about fifteen inches long by about nine inches wide and six inches deep. We may have had one parcel each week, but we always shared them between two, as often there was too much for one person at a time.

The only alternative to parcels from the United Kingdom were the ones from Canada, but I do not recall them as being from anywhere specific, as they never had any names on them. They were bigger parcels than British ones, yet they contained fewer items and every parcel was identical, so all in all, they were not as well liked. The Canadian Parcels had powdered milk in a tin called ‘Klim’, which was just simply milk spelt backwards. Also of interest to us, was

[Digital page 13 left]

that no matter what the variety of jam they supplied, it always had apple mixed in with it. It was surprising what preferences people had. One chap loved butter and would eat a spoonful of it like most people would eat a spoonful of jam!

The Italian authorities issued money to us and it may have been that there were reciprocal arrangements made between the different countries at war. The writing on the back of the notes appears to state that it is only valid inside the camp. I have no recollection of spending this money at all for there was no ‘shop’ as far as I know, but I suppose we would have needed some toiletries, especially with regard to shaving and the like. Any transactions with fellow P.o.W.s would usually have been by bartering, as was the case when I swapped my egg flakes for a book. Apparently, early on, bed sheets were issued in Italy to P.o.W.s but not in England and subsequently that luxury stopped.

[Images with caption] Money issued to us to use in the PoW camp

[Digital page 13 right]

I never got depressed or under the weather mentally, for I suppose I still saw it all as a big adventure, though there were some moments of apprehension. We worried that our own forces might bomb the camp with thousands of our chaps being killed, but such things never happened. I suppose it was the same kind of apprehension as I had on the boat going over to Italy from Africa. We were all comparatively fit and were almost all without exception, single. Some men were all skin and bones but they were definitely the exception. I did wonder if it was the few married men who suffered more than we did. I remember one married chap in the camp with us called Richard, who used to say about his wife, “I never go to bed with my Susan without cleaning my teeth”. Obviously very important to him, but he was not one who pined, in fact he was one of the Cockneys with whom I escaped from the camp.

Another thing with regard to being P.o.W., was that there was always the possibility of writing letters home. Eventually, we were able to let our families know that we had been captured and tell them which country we were in. We had to use the airmail paper issued to us, but we never knew how long any post would take to get home, or even if it been received for that matter! There was nothing coming back to us of course. There was some censorship from the Prison Camp officials, along similar lines to that undertaken by our officers, when we were in action in North Africa. All told, I was seven months in P.o.W. camps, though I cannot remember the exact times, but I would say that I was in the second permanent camp, P.G.53, far longer than I was in the first one. We had no sight of anything outside of the perimeter fence there as far as I know, except for the day we left, when we could at last view the landscape. At the time of the Italian Armistice when the Italian sentries had gone, we managed to go and have a look outside. A fleeting glance of a nondescript hamlet it

[Digital page 14 left]

remained for the time being. It was a much better atmosphere in the camp once the war with the Italians was over, especially as we had been guarded by their soldiers. It was on the evening of the Armistice that we had the football match between England and “The Rest”.

[Drawing with caption] Sketch showing the layout of P.G.53

[Digital page 14 right]

[Chapter title] Freedom

I had no intention of leaving the camp and I was never aware of any escape attempts or plans from our lads. It was not a bit like what you see on the television with regard to Colditz and the like, for we never felt the need to escape. I think as regards to Colditz, that it was an Officer’s camp and escape may have been expected of them whereas we were like flocks of sheep! It probably would have been our duty to escape and I think we would have done something had the opportunity presented itself, but we certainly did not seek to engineer it. A few of the men had been out of the camp on working parties to farms and places. It was through such exercises that somebody taught me how to say the days of the week; the months of the year; this year, next year and last year and how to count in Italian. When I did leave the camp, I had this certain knowledge behind me, which proved to be quite useful and sufficient. Eventually I became quite fluent in Italian for ‘ordinary’ conversations with the people I lived with, but obviously we never talked about ‘shooting stars’ and things like that, but more local day-to-day matters!

Our own officers took charge of the camp in the absence of the Italians after the Armistice and put some of our chaps on sentry duty. The Officers said that we had enough food in the camp from the Red Cross Parcels to last for a week, but we did not know what awaited us if we went out, so we were better off staying put. To stop huge numbers of men wandering off ‘willy-nilly’, our chaps were put on guard duty in the absence of the Italians. After the Armistice, the Italians had to leave and get out of the area before the Germans

[Digital page 15 left]

came, as Italy was no longer Germany’s ally and so for a few hours the camp was left unguarded.

I still felt quite happy to stay, but my Cockney pals whose bunks were adjoining mine, thought differently and were discussing the possibilities. On what turned out to be my last night the camp, something dropped onto me from the bed above. It made quite an impact and when I realised that it was a bug, I decided that I had had enough and that I would leave the camp. So, on September 15th 1943, I was invited to join my pals and I now agreed wholeheartedly to join them and we gathered together a few possessions together in readiness to go. A friend of theirs who was on sentry duty on a comer of the perimeter fence had agreed to let us out. Around midday we went down to see him and he said “oh yes come on, go down there over that bridge; that’s the way to go; south”. He had his bits and pieces on the ground beside him, so his intentions were clear. He wished us luck and informed us that “I’ll be joining you in a minute, after I’ve finished my duty”! That was it and away we went and as far as I know, we never met up with him again.

No one was supervising him and he was in a secluded comer behind a few buildings. I suppose most of the men were inside their dormitories obeying orders so they would not have seen us. That very night the Germans came and took over the camp, fortunately after we had left. Apparently after the camp was taken over by the Germans some of the men hid in various places and were able to escape after the camp had been occupied and guarded again. I think that between one thousand and fifteen hundred of us P.o.W.s managed to escape, with the seven thousand odd who remained, being marched back to Germany.

[Digital page 15 right]

Eight thousand prisoners was quite a lot of men, about twice the current Plymouth Argyle football crowd!

This marked the beginning of a wonderful 10 months stay in the area, before finally surrendering to our forces as they advanced to the North. It was to be a period of real freedom, such as I had never experienced before or since and something I would not have missed for ‘all the tea in China’. This had much to do with the wonderful people living nearby, who kept and fed us so willingly. One of the first things that I noticed after we escaped, were the lovely big bunches of ripe grapes that we could tuck into. So tightly packed were the grapes, that we could just bite into the bunch rather than eat each individual grape. When we were children mother told us never to eat the pips for we would get appendicitis, but given the amount of grapes we ate over there, the pips went down as well! I do not think we saw many others who had fled the camp as we went along. I reckon after about ten miles we came to a small river, which was on the border of two provinces. The province, which the camp was in, was Macerata. The other one was Ascoli Piceno. The river was deep enough to have a good old wash in and from then on. I never saw another louse! Perhaps it was something to do with the state of mind and the different feelings I had, which somehow warded them off.

Just up the slope from the river were about ten houses, mostly belonging to peasant farmers. We must have approached them and were invited to stay there, beneath the houses with the cattle where the straw was put down. That was where I stayed for most of the ten months that I was behind Jerry lines, though later sleeping upstairs with the family and not in straw! I never worried about going any further and as long as things were all right at the time, that was

[Digital Page 16 left]

all that mattered to me. I think there were five of us in total, with two others and myself going to one family and the others to another home.

I stayed at Numerali Quindieci (house number fifteen), which was about a mile outside the centre of Massa Fermana village. The family’s name who I lived with was ‘Forte’ and they had a son of sixteen, Gino and a daughter of twenty one, Pierina. She was the one person who I talked to the most, though not necessarily in private. I understood from her, that Mussolini was responsible for their compulsory education, which was for a minimum of three years. Educated yes, but only up to a point, for she once told me that China was the capital of London. It was hard to believe that, among another large family, there was a young man called ‘Quinto’, who was obviously the fifth child, as that is the meaning of the word. I wonder if he was pleased with his name, or if it was commonplace over there. I certainly thought it strange.

In time, the others I was with, decided to go off into the Apennine Mountains, as they wanted to try and get down into the Vatican City, which was a neutral state. To help ‘spread the load’ a little on the family hosting me, whilst they were away on one occasion, I went and stayed with some of their richer relatives, who lived about one hundred yards down the road. I suppose I stayed there for a few weeks, but most of the time I stayed with the Forte family. Eventually the others came back from the mountains for me and painted a rosy picture of their idea. “Why don’t you come with us to the Vatican as it’s a neutral state and we’ll be safe until the end of the war?”, they asked. I did go with them but only for a few days before I returned alone to the same family again. The Vatican idea never came to anything for any of us. It was too far-

[Digital Page 16 right]

fetched and we probably would not have been allowed in even if we had got there.

We did not have many worries most of the time, but we may well have provoked trouble, for we used to open up grain stores. The fascists, still with some authority, took a certain amount of grain from the peasant farmers, which they held in stores. I was not an instigator, but I used to go along for the excitement when P.o.W.s forced stores open to allow the locals to come along and help themselves to what might be considered their own property. On occasions like this we entertained the locals with a ‘knees-up’; a real ‘knees up, Mother Brown’ performance. We enjoyed that and hoped that they did, whilst wondering of course what was going on! They had a system over there, where half of what they grew was given to the Padrone, who was like a form of landlord. Hens and pigs though, belonged to the tenants not the Padrone, so eggs in a way were a luxury and were worth something to them, almost a form of currency. When we went up to the mountains, we picked up eggs on the way. Often, when we asked for eggs we were offered grapes, so I think in the end we decided that the two words were similar and we had to learn to ask for the right one. Eggs were ‘wovey’ and grapes were ‘ouver’. We ended up with thirty-two eggs in one frying pan to make one omelette! I suppose it was not really very kind to the Italians, since eggs were like gold dust to them. How gluttonous! I know I felt it was wrong, but in my defence, I was there as their guest in the hideaway.

In the Massa Fermana locality there was very little noise, save for an occasional German vehicle, but nothing apart from that came along the road, as far as I remember. Even in the fields and homes there were no tractors or

[Digital Page 17 left]

machinery, so all was quiet, except for people’s voices. It was all wonderfully tranquil with completely silent nights. This sort of atmosphere led to a very nerve-racking experience I had, whilst at the house where I stayed. Unusually for me, I was lying awake in bed one night and in the far distance upstream of our river, I heard the faint barking of a dog. Being alerted, after a pause and silence, I heard a second dog bark. This pattern continued and I soon realised that the sounds were getting closer and that someone was coming along the river towards the house. There were not very many dogs in the area and it would have been quite a distance between each one, so I knew that someone must have been moving along the river to cause each one to bark. Who was it moving around in the middle of the night? Could it have been the enemy of everyone, the Fascists, preparing to capture someone like me, of whom they had been given a tip-off? The closer they got the more fearful I became with my whole attention being focused on the barking. Eventually I heard a dog bark, which I thought belonged to a farm nearby. I really felt I was going to be in great trouble, especially as the noise got closer and closer. I then thought I could hear noises on the other side of our house signifying that the danger had passed. Fortunately, the sounds began to retreat down-stream until I could only hear them faintly in the distance. That signalled the time to relax and what a relief it was to get back to normal and to be able to breathe freely again. I had no real reason to worry and nothing happened, except in my thoughts, but I doubt if I had and have ever felt since, so alone and uneasy as I did during that episode. Phew! It all comes back to me as if it was yesterday. I would not say that I felt so much apprehension during my time in Italy, despite being behind enemy lines.

[Digital page 17 right]

Today, there are all sorts of different sects, some connected with religion as in Ireland and some more concerning nationalities as in the Balkans. Such misguided patriotism and beliefs simply cause trouble and perhaps in some ways, Fascism could be thought of in the same respect. Fascists rebelled against existing forms of government, whilst in Germany under Hitler’s leadership they took control. In Italy the monarchy was dead and was replaced by the Fascist dictator, Mussolini. These events led to the occupation of many European and North African countries. When the Armistice was agreed between the Allies and Italy, the fascists were no longer in power. However, when I lived there with civilians, the fascists were still to be feared, especially given the fact that Germany controlled much of the country, including our area. The local population, along with us escaped P.o.W.s had to be very cautious. Thankfully though, it did not stop the locals from harbouring us.

We used to go to our little village called Massa Fermana about a mile from where we stayed in order to get a haircut amongst other things. I remember once, a young chap came in to the barbers, took some clean towels out of the cupboard, draped them around his shoulders and stood in front of the mirror. He combed his hair, put the towels away and walked out of the salon, just like that! There was also a little pub, known ·as a cantina, in which we would buy vino corte or vino crudo to drink. I think ‘corte’ probably meant it had been boiled and was sweeter and stronger. The better-off family I stayed with did something similar, which made it more like brandy.–Signor Forte would say to us, “you don’t want to get water down in your stomach to rust your insides out, it must be wine”!-

Of course there was never any hot drinks over there, just wine. If there were ever any suggestion of anybody being drunk, normally we would think over here that coffee would be a good cure for a hangover. They however, in the

[Digital page 18 left]

absence of coffee, used to have grains of wheat, which were charred or burnt, before being ground up in a coffee grinder, which they kept on the mantle piece. We were never short of drink and Richard, one of the Londoners, used to say that I was never at all tipsy because I never drank. The glasses we drank over there were about a quarter of a pint and I once counted the number of these glasses I drank in one day. I mostly had vino crudo in the cantina followed by some of the stronger stuff at the richer relatives, where we ended up. The total number of glasses I drank that day was twenty-two! That was an example of the quantity of wine that we could drink. I am not sure if that was enough to satisfy home that I was not avoiding drink! One night walking home from the cantina, Ricardo, as he was know over there, ‘fell out’ and spent the night in a ditch by the side of the road opposite the cantina due to too much vino!

[Postcard with caption] Massa Fermana – Panorama

[Digital page 18 right]

I cannot really remember what I spent my days doing, but the locals used to say to me “you don’t want to come out in the fields with us working, because you’re a carpenter and not used to it. You stay here”. I do remember helping with the wine making, though the grapes were not trodden by foot, but were crushed mechanically. The juice was taken away to be put in a container and once it was clear, the pips and the stems were put back into the wine to colour it, before being strained again. I never saw this vino crudo being bottled however. There was a big barrel of wine in the storeroom on the ground floor behind the oxen along with a jug, glasses and all else that was necessary. The main work was to grow com and to tend the grape vines. They were grown on straight vine fences and pruned down to small stumps after the growing and fruiting season had finished. The summer growth was surprisingly big and the prunings were the only fuel I ever saw being used as firewood to cook the food. Corn was grown between the rows, but little else was cultivated. At one stage though, we had green peas, which were fried on the little charcoal-burning stove. We must have had the occasional salad for I remember there being dandelion leaves for us to eat and with that I was introduced to olive oil, which was used a dressing.

Only two garden tools come to mind now, a ‘vanga’ and a ‘zappa’, which older Devonians would call a digger. The former was a spade with a very small, strong blade and a large handle, suggestive of soil resistant to digging. The oxen worked in pairs, pulling the cart and were also responsible for working the land with ploughs. When Gino had to go to

[Two drawings of a zappa and a vanga]

[Digital page 19 left]

Macerata for his appendix to be removed he travelled there by the cart and returned home just two or three days later by the same means over the rough tracks. It was too soon in my opinion, but he was none the worse for it however. The oxen turned to the right on the command ‘arri-arri’ and to the left when a sound was made by blowing through the lips, as a baby might when blowing bubbles noisily.

[Drawing with caption] Plan of the house where I was so kindly looked after

Although I cannot remember doing anything very useful, I do not think Iwas ever bored. Though I could speak Italian all day long over there, I could not read it and the family had no radio. Perhaps I took out the manure from the oxen and put down the bedding for them. One funny instance occurred when I was in another house, and the girl there had her boyfriend round to see her. Instead of going out for a walk or anything like that, the whole family sat

[Digital page 19 right]

around the fire talking until it was time for him to go. She did not even sit next to him the whole time he was there! One half of the downstairs of the house where I stayed was devoted to the oxen. One quarter was for a workshop, with all the tools and wine, not forgetting a pet rabbit in a hutch and the other quarter was straw and fodder for the cattle. There was also room for the women to do their plaiting. They would plait either seven or thirteen pieces of straw to make baskets and hats, which was known as traitcha. I do remember helping out with this at some point.

One tall old chap named Pedro, who was rather poor as he had no land of his own, lived close to us and he would sell these straw based articles around the area. I never saw him in anything other than barefoot, even when he went on his rounds one day with a fall of snow 30 centimetres deep! It was nice over there to be able to go around barefoot so much, though I do remember Gino had a thorn in his foot once. I got it out for him but it was so painful for him, especially as the soles of his feet were so hard and proved difficult for me too. The snow soon went and is all I remember of bad weather over there, though there must have been some cloud and rain at some point. Once on my own at this little place I experienced an earthquake. The ground began to tremor and heave, but I do not think there was any noise at all. I remember looking at the house and seeing the wall open up and then close back up again! The houses over there however, were built considerably different to how they are in this country.

The living accommodation was upstairs, immediately above the cattle and was reached by means of a flight of stone steps, which were actually outdoors. The door at the top led to the kitchen-come-living room, all very bare without many

[Digital page 20 left]

furnishings, equipment or much comfort. Against the outer wall was a flue with the fire underneath, which was used for the bulk of their cooking. On another wall was a solidly built small fireplace in which charcoal was burnt and was fanned from below. This had no flue and was only occasionally used; perhaps to fry or boil small quantities of food. Gino’s room was alongside the kitchen and was where I slept eventually, even occasionally sharing his bed! One of my pals I had escaped with slept there as well at one point, but I cannot remember where Gino must have been! The other half of the upper floor was taken up with Pierina’s and her parent’s bedrooms. I was not familiar with these rooms, having had no more than a peep through an open door. There was access to the roof space above where I remember seeing some grapes hanging up to dry to become sultanas and some hen’s carcasses. The hens were boiled with soda I think, in order to make soap, which was horrible smelly stuff. I believe the father went up there to catch pigeons when the family wanted some for eating.

The farm had a pond at the front from which water would be dipped for washing the clothes, but was not for drinking. The washing was done in the open and the clothes would then be laid out on the grass to dry in the sunshine, which was always in abundance. It was nice and simple with no fumbling about with lines and pegs. This pond had a small open shrub growing on the far side upon which frogs of a brilliant colour green would climb up the trunk. They looked so nice, but had such a long, drawn out, noisy croak. There was no well at the house and in any case, I doubt if any water could be found that was fit for drinking. Pure water was needed for cooking, so it had to be fetched from the village in earthenware pitchers by the women. They made a ring of rolled up material, which they placed on their heads for comfort as that was where the pitchers would be balanced and carried when full.

[Digital page 20 right]

I might add here and this may explain why the water was not fit for drinking, for the salt they used was obtained from natural sources nearby. The river that we had stopped at to wash in on our first day out after escaping, was only deep in the occasional hollows in its bed. Just up the bank on the far side, small holes used to be dug and very salty water would seep out. This used to be scooped out and carried back to the house before being boiled dry to leave the salt. What could they not improvise over there! Nothing to do with the salt, but a short distance along the track on that side of the river at least two Austrian Jews were being sheltered, though they were much older than we were. They had to be much more careful than us and I believe they stayed close to ‘home’ most of the time, rather than off exploring the countryside as we did. Once, with some other P.o.W.s, we were bathing in one of the deep pools with a steeply shelving bottom. I happened to be

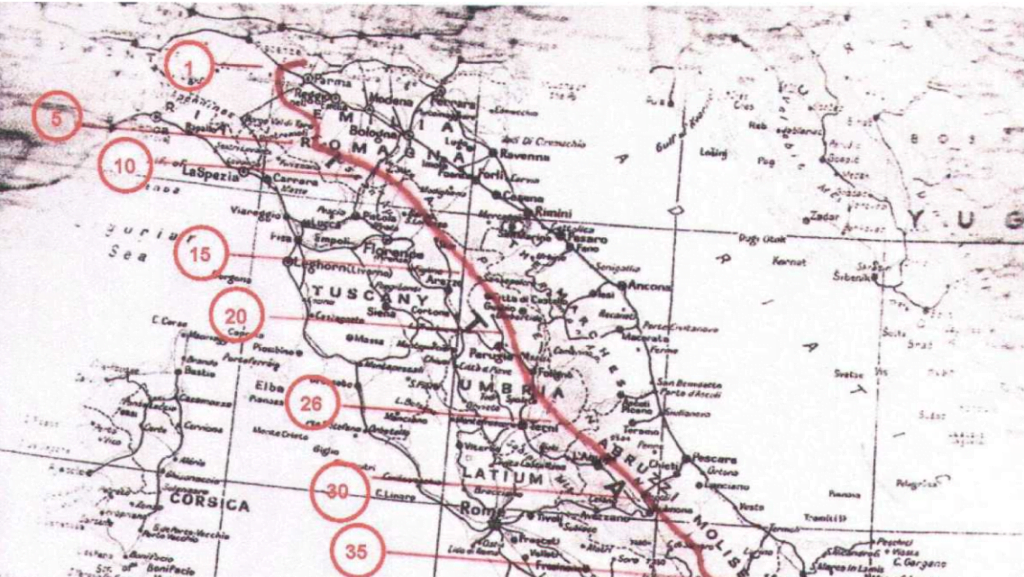

[Image to right of text with caption] Sketch of the Masa Fermana locality

[Digital page 21 left]

alongside a non-swimmer, when he slipped helplessly down and in fact may well have drowned. Needing little effort, except awareness and quick reactions, I was able to grab him and get him back to safety.

There was an open fireplace in the kitchen, with big chains hanging down from the chimney holding a cauldron, where they would boil up spaghetti. Everything was always stirred clockwise, as if it was done the other way, it was said that all the oxen’s teeth would fall out! This was really their only means of cooking except for the little open flue-less fire and they used the prunings from their grapevines, for fuel. I loved to eat past’asciutta, which were long strips of pasta boiled up, strained and put in a dish with tomato, garlic, tomato puree and Parmesan cheese on top, with perhaps a little fried pig meat. We also used to have minestra, which was like a stew with just rolled pasta cut into thin flakes, with runner bean seeds and garlic. The pasta was all home-made. The dough was rolled out very thinly in sheets, before being cut into fine strips. Past’asciutta was as awkward to eat from a fork, as our spaghetti is, but minestra was not so bad for it was a little wider and would be cut across to form small squares. Our chaps nicknamed minestra ‘snowflakes and artillery’ on account of the pasta and beans. The other thing eaten was polenta, which was made from maize flour, garnished with tomato and garlic and tipped out on the table. Everyone would just tuck in with a fork until there was none left. I could not stand the taste of this myself though! They used to bake their own bread in a big oven built into the wall in an out building. This was done about once a fortnight with around twenty loaves made at once. The prunings would be put in and set on fire. All the ash from the prunings would be brushed out and the dough put in, a method similar to what used to be done years before in

[Digital page 21 right]

England. Relatives of my mother, who brought her up, used to have such an oven, which I had seen as a child, though never in use.

I remember my hosts eating their own chickens, as well as pigeons. The pigeons were killed by putting the bird’s head between their first and second finger and whilst holding it tight, they spun it around, until its neck was like a corkscrew. They would then drop the bird on the floor where it would flutter around until all the nerves were gone. Quite a bit of time was taken up by killing the pigs kept in the area. The pig was manhandled and laid down on a plank of wood, which was raised at one end with the pig’s head facing downwards. To kill it, they cut its throat and drained-the blood into a bowl into which some salt had been placed. In a short time the blood congealed, similar to Black Pudding in this country. On the day of the killing, we ate this substance for a meal. Shortly after, the pig would be cut up and we would then eat pork chops. I reckon I probably gained two stone going round to the various smallholdings whenever a pig was killed! The pig’s bladder would be filled with the pig’s fat and in it sausages would be stored to be eaten cooked rather than smoked, at some point in the future. A surprising ingredient was chopped orange peel. The same mixture also went into the salami, which were much larger than the sausages, as different tubes from the intestines were used. Meat running along the backbone was cut into strips and hung from the ceiling of the kitchen, as were the sausages and salami. The fires in the kitchen would smoke all the food hanging from the ceiling, making it ready for eating uncooked.

About one hundred yards up the road, lived another family and I remember watching the woman there treating chickens. Over here cockerels are de-sexed by injection. This woman however, would grab hold of the young cockerels

[Digital page 22 left]

and cut them around the back end and put her hand up inside them and pull out their genitals. With a needle and thread she would then sew them up before putting them down on the floor. She did this at the top of the stairs which were on the outside of houses over there and I saw these poor things then go all the way down the stone balustrade on their backsides, having just been operated on! I can never remember eating chickens over there at all, in fact the closest thing I did eat to it, were sparrows. To catch these, they put some grain under a heavy piece of wood, which was propped up with a small stick. With a piece of string tied to the small stick, when the birds started eating the seed they would pull on the string which sent the wood crashing down on them. I only remember them being eaten on one occasion though. I did have a taste of one, little more, as they are only a small bird and did not amount to very much. I did not particularly enjoy the taste and I feel the same about pigeons. I do remember the sparrow’s bones were soft and were eaten with the flesh.

I once had toothache over there, which was very worrying. It was decided that I would have to go with the son, Gino to have it pulled out by a chap who was probably a farm labourer. I was very apprehensive about this, but what could I do, for I could not let them know that I was afraid. So I went along with Gino, who took me over the fields and over the hills to where this chap lived and worked. When we got in the area, Gino made a few enquiries as to his whereabouts, but we could not find him so we had to come back again. This was much to my relief and funnily enough, I never had toothache again!

Once when we were upstairs above the bar in the cantina listening to the BBC Foreign Service broadcasts, a few vehicle loads of German soldiers arrived, came in and started drinking. I do not think we cared very much, as how would

[Digital page 22 right]

they know we were up there? We were quite often in close contact with them and I saw them down the road, pick up chaps with khaki uniforms on. We would have been in trouble had we been captured in the civilian clothes we were wearing, as it was always said that we could be shot for being a spy. If you were in uniform however, the military conventions governed your treatment. Though we saw these sorts of things happen, we felt quite confident and free of fear as we were so unrecognisable in our borrowed clothes.

I remember from the cantina, a game used to be played using discs of hard Parmesan cheese. Their edges would be bevelled, which allowed the cheese to tilt over as it slowed down when rolled along the ground, enabling it to steer to one side in order to negotiate a comer in the road. The road on which they were thrown, ran downhill for quite a distance and had a short bend after about fifty yards. This bend could be successfully negotiated, if the speed of the cheese was correct, but after that the cheese went according to chance until it came to rest, ready to be thrown again. There was a similarity to our game of bowls with their bias to determine direction. The game was also like playing golf, in that whoever got the cheese to the finish with the fewest throws, won the competition. I think because of the war, cheese was rationed and instead they used wooden discs. That was the only game I ever saw played over there by the men folk.

We used to go to church, shown overleaf, with the people I stayed with, which I liked, and they would go dressed in their best clothes. The women would walk to the church along the roads lined with trees and bushes and would only put their shoes and stockings on when they got about two hundred yards from the church. Up until that point they walked barefoot! What I liked about church

[Digital page 23 left]

in particular was that they always played ‘Moonlight and Roses’ not as a vocal piece, but instrumentally, just to pass the time as it were. Ever since, I have always liked this piece of music, it so reminded me of home. Another peculiar thing was that they have always had trouble with the men and women in the church. Eventually, the half of the church furthest from the entrance door was where the women and women only, had to sit. Likewise, no women were allowed to sit in the half where the men sat. The men were on the side by the exit and towards the end of the priest saying prayers according to the rosary, he would walk around the congregation and always ended up by the exit door in order to stop the men stampeding out to be the first in the cantina! So I am not really sure what religion meant to the Italians, for they had to be separated so that they would not misbehave, whilst the exit had to be guarded to stop them rushing out! It never really applied to us for we were never rushing anywhere, but we sat on the male side of course.

[Image of the church where they worshipped]

We once got wind that there was to be some effort made to get us escaped P.o.W.s back to England by the S.A.S. We had to follow the river down to the coast along a path to meet our chaps on the beach with the landing craft. At the back of the beach were the main road and the railway line, where the ground was relatively flat. We would have to cross these two important communication links in order to get onto the beach. We were well aware by the footsteps we heard in the dark, that there was lots of us going down. Though we knew there were other escaped P.o.W.s in the area, we did not know who they were, but it certainly was an eye-opener to come across so many others. I can still smell today, the fennel growing in the fields as we trampled over it

[Digital page 23 right]

Suddenly we met people coming back who said to us “it’s all finished, don’t go any further, turn around and go back while you still can”. This reminds me of words said in “The Wind in the Willows” those at the back cried forward and those that were forward cried back! What seems to have happened was that someone crossing the road was seen by a German patrol and consequently apprehended. This put an end to our attempted rescue.

I was not really bothered about not managing to be ‘rescued’ because we were quite comfortable as we were; being so detached from the war. We had a roof over our heads and even though I was there at times on my own, that in fact did not really matter a great deal. The thing was that we were exposing ourselves to a certain amount of danger by attempting escape and there was an element of doubt as to how successful it was going to be in any event. If it failed, we could have been recaptured and sent back into Germany and been Prisoners of War again and who knows what that could have led to. We did not necessarily want to be fighting again and we could have ended up being involved in the D-Day landings, not that we knew anything about them in advance of course. Neither did we know that once repatriated we would be returned to England as I subsequently was and not to be returned overseas again.

Around that time, I remember watching a Spitfire zigzagging its way through a valley from up above it, looking down on its wing, which was a nice sight, if only for a few seconds. One day before leaving there, I remember counting over three hundred planes together in one raid going up north somewhere, perhaps across into Germany. In fact, this was one of the few occasions when I actually saw ‘friendly’ aircraft whilst I was abroad, for I never saw any when I was in North Africa.

[Digital page 24 left]

[Chapter title] Repatriation

We did hear a story of an American escaped P.o.W. who wanted to be taken into custody and went around to the Germans to give himself up, but they did not want to know as they were in retreat and had enough to do to look after themselves! Somewhere though, he was taken in by them to help in their kitchen. I remember lying in a gravel ditch under some shrubs, which ran alongside the road and watching the Jerries retreating. Horses drew their guns, whilst the infantry sang as they marched. I always thought from the day that I was captured, how similar they were to us in so many ways. Whilst the Jerries were retreating and our troops were nearing us, the lads up in the mountains came back and we all went to a place called Fermo as the other two had got wind of the fact that British troops had reached there. Whilst there, we met the Count, or perhaps it was Marquis, Bianche, who was said to be the boss of the Fiat motorcar company. He put us up for a while, until we outstayed our welcome, perhaps as we were extravagant with his Eau de Cologne in the water when we had our wash in the morning.

[Image with caption] Count Bianche

[Digital page 24 right]

Some of the British troops we met up with, had a few photographs taken with ourselves and with Bianche and his wife. This group includes Count Bianche, bottom centre, with his wife above him. Using their adopted Italian names from the top left, Pepy, one of our friends whose name I forget; Georgio then Alberto. Below from the left are Ricardo and myself We P.o.W.s are obvious for we are wearing ‘civvies’. Note my ring given to me for my twenty-first birthday by Perina and her cousin Gina, who was from the ‘better-off’ family I stayed with for a short while. The ring was made from a piece of steel, which had been part of an engine. It had two inserts of a black material across the flat surface where a signet ring’s letters could be etched in.

[Image of the ring]

So in the quiet countryside of ltaly I did get a present and one I still have to this day! The two young ladies prevailed upon me to have a photo taken, this in a studio after the spell of pig killing and the subsequent rich feasting. That showed in my face in the picture, as I had been ‘fattened-up’! It is probably just as well that I do not know what

[Digital page 25]

happened to the photograph! They were very nice in their attitude, as were the rest of the family. None of them wished me to leave and, naturally, I liked all of them too. Lovely people.

[Image of the photograph opposite the text]

The photograph opposite was taken at Fermo and from the bottom left; a serving soldier; myself; another soldier and finally Ricardo. Behind us in a striped shirt was Bert Ennis, who was known as Alberto over there. The only other person I remember was Pepy, in the white shirt, who I knew well.

After visiting Fermo we went back to our families with whom we had stayed, to say goodbye before we set off for Naples. When we were about to go, they were all in tears and all the old man could say was “bevi-bevi”, or have a drink as we would know it. We were standing outside the house, which was very convenient for fetching the wine on the same level. I can picture the scene very well, as the one glass that was fetched did its rounds! Wine there was in plentiful supply and was brought out in a jug, which was replenished very generously. While hitchhiking south to Naples, we went to a place on the Adriatic coast called Pescara, after reaching the Naples area. I managed to go swimming once, at Salerno I think. Despite looking forward to the swim so

[Digital page 25 right]

much, it was actually a bit of a disappointment as the water was too warm to be refreshing, something I had never experienced before. On part of the journey, we travelled on board a train in a covered goods wagon, on which there were some Russians, presumably servicemen. It was almost unbelievable how dour and miserable they were. I can see them now, on the floor, as expressionless as anyone could be, as though for some reason, doomed without hope. Far better to have left them after a short while than to have made their acquaintance properly!

I remember going to the cinema, which had a sliding roof that could be slid over as a form of air-conditioning I suppose! The Army did have open-air cinemas set up outside on a big screen, which certainly was one advantage of having such a good climate. I remember a lot of Mickey Rooney films being shown there. I must have at some point, whether from Naples or on route to Naples, visited the Royal Palace at Caserta, pictured opposite.

[Image of Norman outside the Royal Palace at Caserta]

I cannot even remember what we did for money or where we could have stayed, whether with our troops or local Italians. We may have used the money issued to us shown overleaf, though I cannot remember whether I had this money with in in the P.o.W. camps or not.

[Digital page 26 left]

[Images of 1 and 2 lira notes issued in Italy by the British Military Authority]

[Digital page 26 right]

[Images of a one lira note issued by the Italians]

I can picture the main street of Naples with an orange-crushing machine right in the middle of it where we could get drinks of fresh juice. While we were there, we saw French and American troops and there was quite a lot of ill feeling between those two nationalities. All along the left-hand side of the street was living accommodation and that was all supposed to be out of bounds to us, as typhoid was the problem. There were boys at the road junctions, each touting something different. As we went past the corner, a young boy would say “fancy egg and chips mister?”. I cannot remember what was on offer at the second place, but the third one, the lad would say “want my sister mister?”! That was-what it was like in this seedy part of Naples. People talk of ‘see Naples and die’ but from what we saw of Naples at that time it was a pretty scruffy affair. The only thing I regret about my time there was that I never went to Pompei or visited Mt Vesuvius and I have always wanted to see those.

Eventually we had to meet up with our forces in order to be repatriated and that would be it as far as my overseas adventures were concerned. Everybody who had been taken P.o.W. was repatriated to this country, no matter how long they were held captive. On the way home, instead of the boat being a cargo ship as it was on the way over, we sailed on a liner. I do not think it was particularly famous, but it was a big ocean-going one. When we got on board, the first thing we had to do was to sort out the duties, who would have to work in the

[Digital page 27 left]

cookhouse or do the cleaning for instance. The first of our P.o.W.s whose name went up on the notice board, refused to do it. Our chaps said, “look you can’t hurt us, we’ve been locked up for two, three or more years. Being locked up has been our life over here. If you stop our wages, that won’t worry us for all the time we’ve been abroad it’s been mounting up for us, back home”! Some hundred or so RAF personnel being brought back to this country, who

were all Sergeants, ended up doing it all since we refused to do anything. We never lifted a finger on the way back on that boat!

[Digital page 27 right]

[Chapter heading] Return Home

I cannot remember anything of the voyage home but when we approached Liverpool with the Wirral on our right, the first thing I saw was the red brick houses and all the greenery, which thrilled me for in so many of the places we had travelled to, the land was scorched. On the train to London there was a mixed crowd with some ex-P.o.W.s and some civilians who were thrilled to be talking to us and hearing of our experiences. A couple of girls in the compartment heard us talking about where we were going and said to us “come and stay with us if you like”, which could have been an offer of all sorts! I am not sure where I reported back to, but it may have been to Woolwich, which is the home of the Artillery. On August 14th 1944, I was on disembarkation leave, which was for quite a long period. Going home from London I got off the train at Christchurch and was set to walk the few miles to my home. I had not walked very far before mother and father met me in the car, a roadside reunion! This was very nice, especially for them after the time of uncertainty over my well-being and whereabouts. A welcome home party was arranged for me, held at Bisterne School. The reason for this was that I had not long had my twenty-first birthday in Italy before I returned home, so it was a double celebration in a way. Later, whilst I was still in the Army, I was given the honour of placing the first post-war wreath on the Bisterne War Memorial.

On returning home to England, we had to write an account of where we had been and with whom we had stayed in Italy and how we had been helped. So I was able to give them the names of the families I stayed with and how well

[Digital page 28 left]

they had treated me by giving me shelter, food and clothing. The idea was that our government would compensate them for their ‘out of pocket’ expenses. Not so long ago somebody locally in Plymouth lent me a book written by man who was also an escaped P.o.W., albeit in another part of Italy and he stated that they reimbursed the people who had helped him. However this was done at the pre-war rate of exchange so the Italians were in actual fact, cheated. I would like to know nowadays of the family I stayed with and the two ‘children’. They had a brother, Albino, who had been called up on the Russian Front and they never knew what had happened to him. The family said they hoped that in the same way as they were helping me, that someone would be helping their son, but I doubt if he ever came home from there.

Things at home had changed. In front of our house where the land was so flat, temporary runways were laid down and fighter aircraft had flown from them. I had missed that and a few miles further south near Bransgore was another landing strip, which I only found out about after the war. At least two big bomber drones, since demolished, were built in the New Forest and even closer to Bournemouth, one at Hurn. This is now known as Hurn airport, which serves Bournemouth and has the capacity for the largest of jets as well as there being factories built on the site. One in particular was used in the making by Vickers of the popular twinjet, ‘one-elevens’. My youngest brother Pat was working there when he died aged about twenty-eight. Everyone and everywhere was affected by the war and when it came to the bombing of the big towns it might be asked who suffered most out of those of us in the forces, or the helpless civilians? With shortages of so much in the shops, which resulted in rationing of things, including clothing, we certainly had the advantage where food was concerned. Bread continued to be rationed long after the war and it was not refined to the ‘whiteness’ it had been. I remember when we visited one of my

[Digital page 28 right]

aunts, someone had got hold of their first post-war banana and insisted on cutting it into small pieces so that all of us could have a taste.

I was sent to various places whilst still in the forces for whatever reasons and suffice to say, in the beginning, nowhere did I stay for very long. I saw something of Leeds and also of Matlock and it was whilst I was in the North that it was arranged that I would join the R.E.M.E. I think I could have returned to the Artillery but we seemed to have freedom of choice and perhaps I thought the change would do me good. We could state our preferences and I said I wanted to become a Driver-Mechanic so I went in the R.E.M.E. as it was suggested that I joined to train as a vehicle mechanic and dropout part way through to become a driver mechanic. So on December 12th 1944 I was transferred from the Royal Artillery to the R.E.M.E. We still had to wear our uniforms off-duty at that time, which got me into minor scrapes with the Military Police. Once I was walking along the Mall towards Buckingham Palace without my cap on and was stopped by a Military Police patrol. Similarly, I was out walking in Salisbury with mother and father, without my cap on, as I was not really accustomed to wearing it, nor did I like doing so and some ‘Redcaps’ pulled me up. They went around in pairs and ‘had rank on me’ as they were Lance Corporals. As soon as they left I took it off again, but they went around the comer and came back up the street again! In different circumstances I would have been in trouble, but instead I ended up on the laughing side. They wanted to know what my unit was, so I told them I did not have one as I had just come back from being a prisoner of war. “Well”, they said, ”you must know who you have to report to eventually and to where”. I told them that such details would be sent to me in the post and all they could say was “put your cap on” and that was that! But I always objected to wearing

[Digital page 29 left]

a hat. In my seventy-seventh year in cold weather and after having my haircut, I turn to a peaked cap, so I suppose I have changed a little! In the past I have used the saying that, “heads are more waterproof than hats”, though my hat has not been out this winter

I went to Kilburn in London for a time and was billeted out with a civilian couple, who may even have provided me with an evening meal. A lot of the course I did there was to do with filing and dealing with metals. To prove our capabilities we had to square off a certain measurement of a steel rod, perhaps an inch in diameter, then form a square hole in another flat piece of steel to slide over it. This was attached and formed a moveable fitting, rather like a pump. This particular device was known as an ‘Oxometer’, as it measured bull****! I suppose all these things we made were just thrown away in a bin after we had finished them, but I did make a nice open-ended spanner, which ended up in father’s toolkit in his car. We also learnt how to bend, mould, and case harden metal, the latter we did by heating a piece of mild steel until it was ‘cherry-red’ and then dipping it possibly in bone meal. To soften copper, it too was heated to the same degree, before being quenched out in water, which would then make it malleable. At that time in London there was some ‘Doodlebug’ or ‘V2 ‘ rocket attacks on the capital, although the ‘normal’ bombing had stopped. Whilst I was there, I was able to visit the “Stage Door Canteen” which was a forces club open to any nationality. One evening I sat with a French-Canadian who did not like to converse in English and as I had no knowledge of French, we decided to speak in Italian! This seemed to suit us both and for the rest of the evening we carried on quite well speaking only in that tongue.

[Digital page 29 right]