Summary

Jack De Wet joined the British Army as part of the Rhodesian squadron and later became a pilot for the RAF. This account describes his early training and travels that led up to the moment he was flying over German occupied Italy when his plane was attacked and he had no choice but to belly-land in a field. Unfortunately it was a few hundred yards from German barracks. He was captured and escorted across Italy. De Wet escaped with another soldier whilst being escorted on a train and disappearing into the dark and being aided by Italian civilians. Eventually he was recaptured and remained in Stalag Luft One until the very end of the war, where the situation looked dire for all, and they could remain in Germany no longer.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital page 1]

[Letter from Dennis de Wet to Keith Killby]

Dennis de Wet

Texas, USA

December 13, 2002

J Keith Killby OBE

London.

Dear Mr Keith:

I’m sorry I took so long to get to this. I am sending you a copy of my father’s memoirs. I stripped about a third off the beginning about his growing up in Rhodesia as I did not know if this would be of interest to you. I also stripped out some of the pictures that I borrowed from the POW website as I had not asked for permission to use these (they were OK for a family or non-published document). I did put in an internet address (URL) for this for anyone who is interested in seeing these. This is a wonderful site that gives veterans tips on how to write their memoirs and has many links to other relevant websites. I wish my father had had access to this type of information when he was writing his memoirs!

Thanks for the work you do for the trust and thanks for you war service and sacrifices. You are appreciated.

Sincerely

Dennis de Wet

[Handwritten text] Jack de Wet volunteered in Rhodesia. Arrived Cairo Oct ’43 as Test Pilot. Saw Vesuvius erupt and ‘Aida’ at San Carlo. Posted to Caorsica with Ian Smith (future P.M of Phodesia).Shot down and captured near Viterbo. Being taken to Germany with an American [1 word illegible] by train. They overpower guards (knock them out) and escape. Immediate help was given by Italians (in N.Italy) and hidden with a variety of other PoWs. Recaptured trying to get through ‘nomansland’ 24th August above the ARNO 10 days before the allies crossed. In 4 days S.S threaten to shoot him. Greeted in Italy [3 words illegible] by a PoW of 4 ½ years standing. They survive the awful months 1944/45.

[Digital page 2]

MEMOIRS OF JACK DE WET

[Photograph of Jack in fighter pilot uniform, standing in front of his RAF plane.]

[Digital page 3]

FOREWORD

I always wanted to capture my father’s memories, but he was usually reluctant to talk about his war experiences (apart from the more amusing episodes). Eventually in 1987, after much badgering from the family, he began to write his memoirs. Over the next 10 years he wrote, a little at a time, up to his arriving in Corsica. I took a blank tape with me when I went to visit him in 1997 and managed to get him to talk some more about the time after he was shot down and his POW experiences.

My father passed away in 1998 and I subsequently found that there was quite a bit written in his War diary that I didn’t know about. It covered the time from when he was shot down until about the time they were liberated from POW camp. I attempted to put together these overlapping accounts. In some parts I quoted directly from his diary (in italics). For the most part the words are exactly his except for where I had to meld the three different sources. There are a couple of places where I could not understand the writing from his journal. My father may not have spelled the names of all the cities and villages correctly, and I had trouble reading some them.

There are many great photographs that show the conditions in Stalag Luft 1 that were taken [text scratched out] by both prisoners and German Officers. Many of these are on display on the internet on a website called “Stalag Luft 1 Online”. This can be viewed at (URL) [Link broken, 2018].

Dennis de Wet

December 28, 2001

Copyright: Dennis de Wet

[Page endnote] Picture on cover: Jack in Naples with Mt. Vesuvius erupting in background

[Digital page 4]

THE WAR BEGINS

I was spending the day with a friend of mine, Ivan Magwire, on Sunday the 3rd of September 1939 at his home in the Salisbury suburb Ardbennie in Rhodesia when at one o’clock we heard on the news that Britain had declared war against Germany. After lunch, we took our bicycles and reported at the Drill Hall army barracks to volunteer. There were several hundred other young people doing the same thing. We were rather taken aback when a fierce looking Sergeant Major Crookes told us get the hell out of there, and that the army would let us know when they wanted us!

And so the war began, a war that was to cost many millions of lives and change the lives of many millions more people. In due course, my army call up papers arrived. I was instructed to report to Brady Barracks in Bulawayo. Before boarding the train in Salisbury I was one of a dozen recruits involved in a fight at some bar. The next day on arrival in Bulawayo, found that I had broken a bone in my right hand. So, of course, there was no rifle drill for me, and I was put on light duty. Light duty in the army meant that you were not confined to the sick quarters. You were, nevertheless, confined to the barracks and performed light duties around the camp such as picking up cigarette ends and paper. What a dreadful organization the army turned out to be. I was confined to barracks whilst all my pals were allowed passes after 5 PM.

I then heard that they were short of a bugler and, naturally, volunteered. It turned out to be a key job in the army as buglers were as scarce as chicken teeth. Once my hand healed I tried to get back to my platoon, but there was no way that the camp adjutant would allow it. He did not want to lose his bugler!

[Photograph with caption] Jack and his father

[Digital page 5]

Shortly afterwards a new army camp opened in Gwelo and I was transferred there. I was there for three months and was then sent to the Umtali Training camp. This was supposed to be a motorized unit, the modern version of a cavalry regiment and therefore I now had to play their instrument, a trumpet. Quite different to a bugle, the trumpet has eight notes instead of the five that the bugle has. Of course the military calls are also quite different. I much preferred the trumpet.

I was still trying desperately to get out of headquarters staff and into a regular army unit. The opportunity presented itself one hot October day when I found that every time I blew the trumpet my nose started bleeding. I went to the sick bay and saw the doctor who declared that I had high blood pressure and should not be a bugler or trumpeter. I was promptly taken off these duties and transferred to the Signals section. In time the Army transferred me to the Signals Corps in Salisbury at K.G. VI Barracks.

[Photograph with caption] Jack and brother Henry

I found I took to Morse code and signals like a duck to water and this was a very enjoyable part of my army career. After 6 months I was well ahead of the rest of the platoon and so the army in their wisdom decided to take me away for a month on other duties.

The other duties turned out to be guard duties at the detention camp in Gwelo. The camp was for those sentenced by the army to periods of prison ranging from 2 weeks to the duration of the war for crimes such as theft, striking senior NCOs [Non-commissioned Officer], desertion, etc. This was commonly known as the “Glass house.” For me, this was a disaster. To be a prison guard was hardly something one joined the army

[Digital page 6]

for. Even the regular guards were hard faced, tough characters, and the sergeant, Oliver Cawood, was sentenced to death a few years after the war for murdering his wife.

On my first long weekend off, I went to Salisbury and applied for a transfer to the R.A.F. [Royal Air Force] as a trainee pilot. Along with a friend of mine, Johan van Schalkwyk, I began my initial training at the beginning of 1943. We both passed and went to Elementary Flying School at Mount Hampden and trained on Tiger Moths (bi-planes). Van Schalkwyk was a natural pilot and broke all records by going solo in under 3 hours. Shortly afterwards he developed a severe ulcer and was “scrubbed.” So that was the end of his flying career. I took very much longer to go solo, something like 12 hours of dual flying. My instructor was a 1914-18 pilot by the name of Leibrandt. He was a crusty sour fellow. Whenever he had an argument with a pupil, he used to say “Laddie, I used to juggle with death in the sky when you were still a gleam in your daddy’s eyes.” Our brief ground instructor, Adrian Griffith, had lost an arm in North Africa in a Hurricane fighter. He later became Secretary of Agriculture in Rhodesia.

From Mt. Hampden, I went to Cranborne airfield in Salisbury, to train on Harvard trainers. I had preferred training for a fighter squadron rather than a Bomber squadron. Fighter pilots were inclined to look down on bomber pilots, and thought of them as bus drivers. At Cranborne I shared a room with Gerard Graham, who after the war was to start CAPS, the pharmaceutical manufacturing company.

[Digital page 7]

[Photograph without caption] A portrait of Jack in uniform holding the Platsis cup.

A few weeks before the end of the 3-month course I was awarded the Platsis cup for the best all round pilot on the course. Shortly thereafter I moved into the officers mess as a cadet officer. My instructor, Sergeant Yarwood, now called me “sir.” I felt uncomfortable with that and told him so. Bert Yarwood had been a great help to me. I’m sure without his help and understanding I would never have made it to the top.

Along the way, several pupil pilots on our course were killed in flying accidents. One of those killed was a roommate of mine, a Welshman named “Blondie” Brock. It was sad when I went to my room and saw ground personnel packing up Bondie’s clothes from the other locker. Harvards were generally good training planes, but if you treated them wrong they were very unforgiving. They gave you no second chance. Ninety-three of us had started the course but the weeding out process or “scrubbing” was a continuous exercise throughout the training period. Because of lack of flying sense, failing tests, etc. plus several fatal accidents, only 35 of us were eventually to receive our wings.

[Digital page 8]

THE MIDDLE-EAST

We were now given 10 day’s embarkation leave before being posted to our various operational training units and eventually to our squadron. There were 6 of us white RAF officers and about 300 black Rhodesia African Rifles troops who were to go on the trans-Africa route. The journey started in Salisbury by train, via Bulawayo to Lusaka in N. Rhodesia and on to Elizabethville in the Belgian Congo. At Elizabethville we changed to Belgian Congo Railways with their wood burning locomotives as far as Alberville in the Congo. From Albertville we travelled by Lake Steamer across Lake Tanganyika, then by road, then rail and eventually by Lake steamer across Lake Victoria to our destination at Kisuwu. We spent a few days here in Kisuwu, and then flew by DC3 to Khartoum and finally Cairo. It was a tiring, but very interesting trip. What impressed us the most was the savage state in which much of Africa still was and the vast amount of good untouched agricultural land.

It was now October 1943 and we spent some weeks in Cairo before being posted to our operation-training unit at Abu Sweir just north of the Suez Canal. A few days later we were flying in our Spitfire MKV’s. What a glorious airplane it was to fly! The plane had virtually no vices. We were here through Xmas 1943. Jim Pierson, my old friend from Cranborne, Keith Burrow, who later worked for Tobacco Auctions and died in 1960, and Red Hurrel, a Canadian. Two other notables on our course were the exiled King of Greece and the exiled Crown prince of Yugoslavia. Both were useless pilots, but they were given their wings all the same.

[Photograph with caption] Jack and Jim Pierson at the beach in Palestine

[Digital page 9]

We spent Christmas 1943 at Abu Suier and shortly after that we passed our exams and were posted to a transit camp at Cairo. From there I was posted to a pilot pool at Bengazi and then to Tripoli. They were all still Arab countries with the same smells and the same beggars, except that these countries had been under French, Italian and German occupation. The Arabs did not seem so nasty or insolent as the ones in Khartoum or Cairo.

[Photograph with caption] Jack and friends

[Digital page 10]

ITALY

While I was in the pilot’s pool, a notice came around that a vacancy existed for a single engine pilot at a maintenance unit as test pilot (anything to get away from the boredom of sitting around waiting for a posting to a squadron, which may take many months!) In any case, it sounded like a glamorous job, and so I applied, was accepted, and posted to 113 maintenance unit at Capodichino Airport, Naples, in Italy. The pilot I was replacing, Ft/Lt. Banger Welman [Flight Lieutenant] gave me the cheerful news that of the previous 12 test pilots on the unit 9 had been killed in flying accidents. We repaired aircraft damaged in the Mediterranean area of operations, and the test pilot’s job was then to test these aircraft, mainly Spitfires, and certify them fit for service. They would then be returned to active service.

On one such test flight of a Spitfire Mark IX I found, on coming in to land, that the wheels would not lock down. I would, therefore, have to belly land. After repeated attempts, I eventually got the undercarriage to lock down and was able to land. The investigation, found that the oil leads to the wheels were connected up the wrong way round. It was a scary experience and influenced me to apply for a transfer immediately. I didn’t think I had come all the way to the battle zone just to be killed in a flying accident. The front line was then not many miles north at Anzio and several fighter-bomber squadrons of the US Airfare operated from our airfield. Mt. Vesuvius, just outside Naples, had been rumbling for some time and one day it erupted and gave us a fantastic scene of a volcano in full flight of eruption. It was the biggest eruption for over a hundred years. I took off with my camera in a spitfire and managed with great difficulty to get a few very good photographs from 10 to 15 thousand feet. I had not realized what a difficult task trying to take photos out of the side canopy and flying the spitfire at the same time would be. Pompeii escaped damage from the volcano this time, but several villages in the valleys below were destroyed. Another attraction in Naples was the San Carlo opera house where we saw a number of operas like Aida.

While at 113 Maintenance Unit, I visited an airfield nearby at Caserta where my old friend Jim Pierson was flying in 145 Squadron of the RAF. The C.O. [Commanding Officer] at that stage was Squadron Leader Neville Duke who had been our Chief Flying Instructor at Abu Sueir. Neville Duke at that time was 21 years old and already had over 20 victories in the air with the DSO [Distinguished Service Order], DFC [Distinguished Flying Cross] and bar. He was to carry on flying after the war, first with the RAF, and then as a test pilot. He still appears regularly at the Farnborough Air Show in England.

My transfer now came through and I was posted to the Rhodesian squadron, 237, which was flying out of Corsica. It was great to be on a squadron of Spitfires, but I was a very new boy. A pilot who had only a few weeks’ seniority was a very superior guy. This is where I first met Ian Smith. Ian Smith later became Prime Minister of Rhodesia. He had just rejoined the squadron after having had a nasty accident in North Africa and having spent some months in hospital.

[Digital page 11]

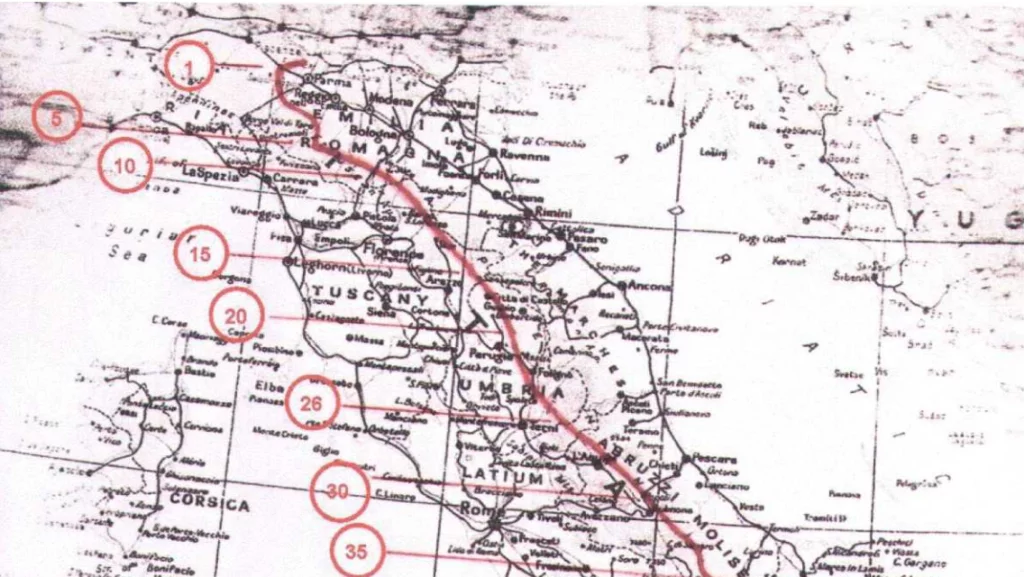

[Map with caption] Corsica and mainland, Italy

We moved to a newly constructed airfield outside Bastia in Corsica and the day we arrived we were instructed to dig trenches for ourselves in case of German air raids. The following evening, air raid sirens sounded and the Luftwaffe had arrived. When I reached my trench I found it was already occupied by someone who had not completed his own and I could only get my head into it. The first bomb hit our radar, and after that the Germans had a great time destroying or damaging over 70 aircraft on the ground. No one was badly hurt or killed in the attack. Two days later, the new Spitfire Mark IX replacements began arriving and we were soon back to full strength.

[Digital page 12]

CRASH, CAPTURE AND ESCAPE

Our main duty was to escort bombers on the West Coast of Italy, and the South of France. The Luftwaffe had, however, taken a mauling. They were reluctant to send their remaining fighters against us. On the 26th of May 1944, we were escorting American Mitchell Bombers over Northern Italy, when I spotted a JU 88 in the distance. F/O [Flying Officer] Ian Smith and I were detailed to engage him, but he disappeared into some clouds and we turned for base. On the return flights we normally went to ground level to attack any German ground forces or targets of opportunity that we saw.

On this occasion, we attacked some heavy German transport crossing a bridge near Orbetello. Ian Smith was my number one. For him there was a measure of surprise, and by the time I came down a matter of seconds later, several German light FLAK guns were waiting for me. We gave the transport lorries a good plastering. I turned into one of the FLAK emplacements and literally blew them out of the ground with a few bursts of my 20mm cannon. Two other FLAK emplacements had, in the meantime, synchronized their fire on me. I was hit by 20mm FLAK, I felt my brand new Spitfire Mark IX shudder a few times.

I pulled out of the dive, but I could feel that I had lost some control. I would not be able to gain enough altitude to safely bail out and parachute down. I glanced down at the instruments and saw the engine temperature gauge going mad. The cooling system had been hit and there was only one thing to do – close the throttle and try to force-land. I would have to belly-land in one of the nearby fields or, alternatively, the beach. The coast was only a few miles away.

My decision was made for me. One wing tip had been torn off and that made gliding, even at a fairly high speed of 125 miles per hour, very difficult. With some luck I managed to bring my Aircraft down in a nearby wheat field. I came in on the plane’s belly for about two hundred yards before coming to rest in a shower of dirt and wheat stalks.

Suddenly, everything was very quiet. Looking out of the cockpit, my heart sank when I saw that I had landed a few hundred yards from a German barracks: The German soldiers were pouring out of the barracks in their green-gray uniforms. I called Ian Smith on the radio, and was delighted to find that it still worked. I hurriedly asked him to write to my mother and tell her that I had landed safely. By then there were shouts of “Raus! Raus!” coming from outside the Spitfire. My training led me to lower my flaps without thinking. I pulled the flap lever, and there was a loud gushing sound as the air escaped. The Germans must have thought I had pulled the fuse on a bomb! They leapt back in consternation and, with several sub-machine guns leveled menacingly at me, they shouted even louder, “Raus! Raus!’’ I could do nothing but surrender. They lost no time informing me that I was a prisoner. “For you zee war is over,” one of them shouted. After I climbed out of the cockpit, I realized that my captors were from the Hermann Goering division of the German Army. They were not the friendliest of people to be captured by. A long argument ensued amongst them. It was, I gathered, about whether they should shoot me on the spot or take me prisoner. Evidently, the people who had manned the FLAK emplacements that we had just attacked were from the same division. The R.A.F air attacks had been taking their toll on the Germans.

[Digital page 13]

About an hour after I was captured, I was sent under escort to a nearby military post at Orbetello where German Intelligence debriefed me. I waited there for the arrival the escort guards for the first leg my journey to Germany. My treatment was better than I expected for my first night in captivity. A German officer who spoke fluent English gave me a much-appreciated pack of cigarettes. This was offset by a feeling of hopelessness that I felt in the pit of my stomach. It was painful for me to come to terms with the fact that I was now a P.O.W [Prisoner of War]. Surely, I thought, this was just something that only happened to other fellows. I kept visualizing myself back on the Squadron in Corsica, and having a drink with the other fellows in the mess.

Later in night my guards, Fritz and Hans, arrived. At 4 a.m. I was moved by motorcycle to a Luftwaffe P.O.W. collection centre at Viterbo where I spent the night. We had bombed and strafed the airfield at Viterbo a few days earlier, and were convinced that it was unserviceable as an airfield. To my surprise, I noticed quite a few Fiesler Storches and some FW 190’s cleverly camouflaged and tucked away next to some gutted airfield buildings. At Viterbo, another prisoner, Lt. Harold Hamner of the 27* Fighter Bomber Group, USAAF [United States Army Air Force], joined me in my cell, Harold, who was 21 years old, came from California. He had been in America only three weeks earlier, and was in a state of shock. He was shot down while flying a Thunderbolt.

[Map showing west coast of Italy where De Wet had been captured and transferred.]

For the next few days the drill would be to be laid up during the day in some civilian jail, while numerous Allied air-raids were going on, and being moved by road transport under the cover of darkness. Allied air superiority was such at this time that no German road transport was attempted during daylight hours.

May 30. We spent 5 days in Pistoia, near Florence. We were put, under escort, on a German troop train. We were bound for a POW camp in Germany. Because of heavy RAF and US air force activity, all German troop movements were done at night. We spent most of the day in a cell in Florence. During the confusion of an air raid, I was able to steal back my escape kit and personal belongings from the Germans. I found an old 10-inch rusty bolt under some straw in the cell. I hid this in my battle dress jacket in the inside pocket. At 10pm we left Florence.

We were put in a first class compartment with our two guards and a German Major. The plan we had worked out in advance, was that I would attack the guard sitting opposite me and Harold would

[Digital page 14]

attack the guard who was sitting next to me when the opportunity arose. We would then try to make it to the safety of the hills by daylight. At 1:00 a.m., and about ten kilometers from Pistoia the train slowed down enough for us to attempt an escape. I decided that it was “now or never!” I stood up to throw a cigarette out of the window and smashed the guard’s head with the rusty bolt. He collapsed. The ensuing fight lasted about ninety seconds. Harold struck the guard next to me and jumped out of the window. I turned toward this guard who, along with the officer, was by now very alert and a desperate struggle ensued. By now the train was gathering speed again. I got halfway out of the window, and with a lucky kick to the guard’s face, fell out.

I landed with a sickening thud but, incredibly, suffered no serious injury (apart from some profusely bleeding gashes in my head where the German hit me with his rifle butt). I found Harold about a half mile back on the railway tracks, completely unhurt. When I later questioned Harold about his hasty exit from the train, he replied that he hadn’t thought that I was serious about the escape plan.

It was now about one o’clock in the morning and completely dark. The train had stopped and backed towards us. The soldiers began to search for us, but eventually gave up, and the train set off again. In an attempt to get as far away from the railway as possible, we set of at a right angle, or easterly direction, from it. Traveling in the dark turned out to be very difficult. We soon found ourselves traveling through terraced vineyards. Every time I fell, my wounds opened up and began to bleed again. By first light we reached the foothills of the Apennines, and breathed a sigh of relief. I was exhausted from lack of sleep and loss of blood. Good fortune was with us that day. The people at the first house that we stopped at, not only gave us a warm welcome, they gave us a cup of coffee to drink and a raw egg each to suck. They also introduced us to a British Army Medical Corps Corporal who had been hiding in that area for seven months. He escorted us about a mile further up the mountain. We holed up in an old disused hut. I was still so weak from the loss of blood that I was unable stand up. A local Italian woman nursed me back to health.

[Digital page 15]

BEHIND ENEMY LINES

We were in German occupied country and there seemed to be German soldiers everywhere. How we were not recaptured, was a wonder. The Italian civilians were wonderful to us. Despite the heavy German presence and rewards that were posted for the capture of allied escapees, the Italians never revealed us to the Germans. They brought us rich food, goat’s milk, and fresh fruit and vegetables, and we soon regained our strength and recovered.

[Note from editor] I have interspersed excerpts from Dad’s journal (italics) with his other writings from here on. Although the journal entries sometimes jump from present to past tense, I have not altered this.

June 4. We started heading east, but after a few hours of traveling, found that we were still far too weak and returned to our hut. “Tigre”, the Corporal made us feel welcome.

June 6. Harold and I met Colonel Sanddrucci and his wife, who gave us soap, a comb, brush, towel, wine, and 500 Lire.

June 7. I met George Ristorick a private in the Coldstream Guards, captured at Tobruk in 1942. George had a charming personality, and being a real Don Juan with the Italian girls, he had good contacts everywhere and lived a life of comparative luxury. Proof of this was when he immediately took me dancing with him at Captain Venturi’s villa that same evening. The two Venture girls, Vilma and her sister, were excellent dancers and hostesses. They were both very fair and did not look Italian.

June 9. I met Wilmer Hochstatter, a tail gunner on a Mitchell bomber in the 348th US Bomber Group. A Flight Sergeant, he came from Mendota, Illinois, and was shot down two days earlier. Wilmer and I later became the best of friends and were only separated owing to the fact that I was recaptured and he was not.

June 10. “Tigri”, Harold and Wilmer and I had dinner with Colonel Sandrucci at his villa. This consisted of a lovely seven-course dinner plus wine and champagne. The only disadvantage to this was the fact that we had to have sentries posted and to continually on the alert for Germans.

June 11. Signor Rossi from Pistoia visited us, bringing with him a very handsome gift of 350 cigarettes. They were worth their weight on gold, and very welcome. We spent a pleasant evening in the friendly village of Luppiciano, We felt comfortable and totally at home. The attraction in Luppiciano the two beautiful daughters of Captain Venturi.

June 12-16. Met Rosanna Beneforte, a charming young student from a Florence university. A student in languages, she could speak Italian, French, Spanish, German and English. In the

[Digital page 16]

succeeding four weeks, Rosanna was an angel to me. She very generously provided my comrades and me with money, food, clothing, and sincere friendship. It was Rosanna who later tried her best to persuade me not to leave the area, even going to the extent of offering me accommodation in her family’s villa. That would, however, have endangered all of their lives. I still remember her with a sense of admiration.

June 17. Having accepted an invitation from the “Doc”, George and I went to his villa near Santa Morah (Santomoro ?) to enjoy a hot bath. This was to be followed by a much-anticipated dinner. What occurred was instead, in retrospect, an amusing incident. Soon after we arrived, there was a commotion and panic all over the villa. The Germans had surrounded the building. George was in the bathroom. I was unceremoniously pushed under a bed in the old lady’s bedroom. The Germans began a thorough search of the villa. An officer systematically went through every room in the villa. This continued for a full 30 minutes. I lay trembling nervously in my awkward position until eventually the ‘all clear’ was given. The reason for the inspection, as it turned out, was that Field Marshal Kesselring moved his headquarters into the area and accommodation was required for many officers. While George leisurely lay in the bath lathering himself, two German officers had stepped in, stopped short, said “pardon us” and hastily withdrawn, closing the bathroom door politely.

June 19. We had a second (and last) dinner at the Sandrucci’s villa. This time the party included George.

June 20-23. We tried to cross the railroad North of Prato, but turned back in disappointment, as we found large enemy troop concentrations in the area. During our absence, tragedy struck San Morah. Following and attempt by the partisans to cut German field telephone wires, the Germans entered the nearest village to the incident, Santa Morah (Santomoro ?), and shot 5 innocent men. I was shocked by their callousness. So much for the Germans being a “cultured” race!

June 23-30. Harold, Wilmer, and I made a hut in the mountains. It was well camouflaged, conveniently situated for water, and centrally located between two villages. The steep climb for 3 miles from the valley discouraged any Germans form taking a stroll and finding our hut by accident.

July 2. Entertained visitors at our ‘barracca’, amongst these were Doe and his wife, Fabio, Neva, and Veronica. Our abode was called ‘Rigoletto’ and temporarily suited the name very well.

And so the days passed by. We lived a healthy outdoor life with more than enough exercise. Every day was crammed with more thrills and excitement. At Rigoletto we had established ourselves very well. We had, between the three of us: 5 blankets, frying pans, pots, dishes, plates, cups, one broken wine glass, a few spoons. We had enough food for about 4 weeks, but little knowledge of cooking. We resorted to frying everything in olive oil. We had fried eggs, fried bread, fried potatoes, and fried onions. We washed it all down with some of the delicious Italian red wine. As we were soon to discover, this was just too good to last forever.

[Digital page 17]

At 5:00 pm on July 16, the quietness of the woods was shattered by the sound of machine guns. The Germans were systematically machine-gunning their way through the woods and scaring everyone in the vicinity. We soon concluded this was a most unhealthy place to be, especially after the Germans started to dig their defensive gun emplacements less than four hundred yards from Rigoletto! With sadness we hurriedly packed our few belongings and left.

Much to our regret, we now found ourselves sleeping on the hard ground with only the trees for a roof German troops were everywhere, and we were forced to hide by day and forage for food at night. The only sensible option for us now was to make for the front lines, no matter how risky it might seem. We could not go on living this way. Wilmer, George and I decided to set out for the front lines, but Harold, who had contracted dysentery, preferred to stay, so we split up.

To this day, I don’t know how we made it out of there. New German divisions had arrived and the place was swarming with them. Every way we turned, we seemed to come up against more of them. On the day of my escape I had swapped my air force gear with an Italian labourer for an old suit of his. And so, with plenty of olive oil in my hair, I vaguely resembled an Italian peasant. Together we passed for a pitiful party of Italian peasants. Consequently, unless we were stopped and interrogated we were fairly safe, but we still had to be very careful. Our luck held, however, and we made it to the hills on the opposite side of the valley from Santa Morah (Santomoro?). It was a blessing to find a friendly reception in the form of a good meal and a bed at the house of Lindo in the little village of Viguano (Viano?).

August 2. The Italians had by now lost all their enthusiasm for opposing the Germans. It was no longer a novelty for them to harbour British and American escapees. Conditions were worsening for the Italian Villagers. The Germans were confiscating livestock, poultry, horses and any grain they could find. We were once again forced to lay-up in the woods. We decided to split up again. Wilmer went with me, and George remained behind.

August 3. After crossing the Pistoi-Serravale railway and several guarded areas during the night, we made Mont Albano by daybreak. Tired, hungry, and thirsty, we turned into some thorn brush to hide for the day. The fact that we had only a loaf of bread and a bottle of water between us did not bother us as we were now used to this manner of existence. We were determined to put up with all manner of hardship in order to make the British lines. Once I was healthy again, we started moving south. We always moved south toward the allied armies, or in this case, the South African 6th Division that had stopped at the River Arno for regrouping.

August 4. After our all night march we had reached a point on Mt. Albano just above the little village of Vinci. This was about five miles behind German lines. We met Walter Banci, a former Italian Army Officer from Prato here. We were persuaded to lie low and wait for the next British advance. The river Arno was mined on both banks and the fighting although sporadic very heavy at times. Walter Banci advised us that it was, therefore, sheer foolishness to try at this time to cross the Arne to reach the British side. For a while things were better for us. We were once again a novelty and everybody was keen to do something for us. Most of the Italians in this area were evacuees from the besieged towns and food was consequently scarcer than ever. Wilmer and I spent

[Digital page 18]

the last of our money on such delicacies as meat (15 shillings a pound) and fruit (three shillings for 10 peaches).

Another week went by and there was still no sign of an advance by the British army. The only activity seemed to be the daily exchange of artillery shells between the German and Allied artilleries, and the occasional patrol during the night. It was clear to us, with no advance by the British, the odds of us being discovered were increasing by the day.

[Digital page 19]

RECAPTURED!

On the afternoon of the 24th of August, I decided to go and have a “look” at the lines. Accompanying me were a Russian Officer and an Italian partisan. We soon found that it was impossible to travel straight and the only hope of reaching the river Arno was by traveling along one of the aqueducts. It was hard going as well as nerve racking. We sometimes passed only few feet from German soldiers, and once came under heavy fire from Allied artillery for a full 20 minutes. Eventually we reached an area that was in effect no-man’s-land. We were in the unfortunate position of being within a hundred yards of the German Advanced field Headquarters. Our aim was to get within a half mile of the river, and then to lie low until one o’clock in the morning and then attempt a crossing in the early hours of the morning. I looked at my watch. It was 7:15. I decided to travel for another 15 minutes. At 7:20 patrol of German Signalmen stumbled onto me in the aqueduct, and took me prisoner. I was 300 yards from the river and 400 yards from the nearest Allied machine gun post. 10 days later the British advance took place.

[Map with caption]

Prato is just to the North of this map. The road from Empoli to Signa (which is right at the “S” of Settimo) follows the river Arno, which then flows across to Firenze.

[Digital page 20]

[Map with caption from editor]

I’m guessing that this is the area (between Empoli and Signa) where Dad was captured.

Needless to say, I was pleased that Wilmer was not with me. At least he was still free. The Russian and Italian managed to slip into some bushes when I was discovered and they still had a chance of making the lines during the night.

I was sent to a Durganslager, or transit camp. That same night a little German “Volkswagen” took me to a prison cell in Pistoia. S.S. guards moved me the following night to Abtione in the mountains North of Pistoia. I discovered that my new temporary lodgings would be in the Gestapo H.Q. prison. What a friendly atmosphere it had about the place! They gave me no food for three days. I was put in solitary confinement and then was interrogated again. Because they captured me in civilian clothes, I was accused of being a spy and various other crimes. They said that I dropped in by parachute to lead the Italian partisans. The only thing they didn’t do was to shoot me on the spot, although they threatened to do this more than once.

They continued to accuse me of being a spy and because I wouldn’t admit to it, they got mad at me. Every morning I was marched out, stood in front of an open grave, and then told that I was to be shot. The only thing I could do was to pray and [Text redacted]. Eventually the Germans gave up on me and I was sent on my way along with about ten other R.A.F prisoners to Stalag Luft One at Barth-am-Ostsee in the Pomerania on the Baltic Sea.

We travelled via Bologna, crossing the Po near Mautnua, Trento Brenner Pass, Innsbruck, Munich, Augsburg, Ulm, Stuttgart, Karlsruhe, Luduwigsanven, Mannheim, Darnstadt and Franfurt, (reaching Wetzlar on September 3, 1944). We eventually arrived at Frankfurt-am-Main on a Sunday evening, where we got a very hostile reception by the large crowds at Frankfurt station. Frankfurt had recently sustained heavy bombing by the RAF and every second person seemed to be in mourning. I was now traveling with two British Airborne troopers. We were probably saved because we claimed that we were Spitfire pilots. Germans hated bomber crews but for some strange reason, admired Spitfire pilots. That helped a great deal and probably saved us from being beaten and kicked to death.

[Digital page 21]

STALAG LUFT 1

After a week’s stay in Wetzlar I was transported, along with 99 other R.A.F. [Royal Air Force] and U.S.A.A.F. [United States Army Air Force] P.O.W.s, through Germany via [Text redacted] where we bombed on 5th September by a formation of American Fortresses. We continued through Marburg, Kassel, Braunschweig, Magdeburg, Potsdam, Berlin, and eventually to Stalag Luft 1 at Barth, situated halfway between Staisund and Rostock, on the Baltic Sea.

The welcome we received at Barth was a strange. A sea of faces greeted us from behind thick and foreboding wire fences. The faces grinned, each with their own expressions that seemed to say “hiya, fellas”. We were recruits or “rookies” once more. The first “old Kriegie” to speak to us shook us as much as any Spandau or Stuka could have done. He proudly announced that he was the camp surgeon, was captured at Dunkirk, and had been a “Kriegie” for 4 1/2 years. He wanted to know what it was like to be free.

The camp contained something like 10,000 prisoners. About 2000 of them were R.A.F., South Africans, and French. Six were Rhodesians. There were also a number of prisoners-of-war from Poland and Czechoslovakia who had been serving in the R.A.F. On arrival, the first thing that happened to us was that we were “de-loused” and they gassed our clothing in a delousing cabinet. We thought it was amusing but necessary hygiene because of all the fleas and other animals that might be joining us. Then we all had hot showers. We were processed just like you would be when going to prison in civilian life. We were photographed, fingerprinted and identified. At the end of the war, I managed to raid the prison camp offices and rescue my “criminal” records (which I still have).

Following the processing, they allotted us our barrack rooms. I was taken to block number ten in the British sector. There were twelve rooms in the block with sixteen prisoners to a 14 by 14 foot room with eight double-bunks. In my case I was in a room with several other R.A.F. POWs and eight Czechoslovak POWs who had been with the R.A.F. for several years. They were never that friendly to us, so we were, in reality, two separate camps. They spoke Czech, which none of us could understand, and they could all understand English. They were very conservative or insular and kept to themselves. By the end of the war there were seven or eight Rhodesians, all ex-R.A.F in the barrack room.

Our senior Officer was Group Captain Green who had farmed just outside Salisbury. We came from varied backgrounds. One of the prisoners, John Baldwin, had worked for the Rhodesian Broadcasting Corporation. Most of the others were farmers or civil servants except for Terry Fynn who, after the war, ended farming next door to me.

Terry, though now retired, still lives nearby after 50 years. At the beginning of the war Terry was in Britain training to be a Roman Catholic Priest. As with many people at that time, though, he was caught up in the war. After the war he decided to go into farming. Terry was a bomber pilot

[Digital page 22]

in the RAF and also the sole survivor of a crew of eleven when his plane was shot down. Terry is a survivor. A gang of terrorists ambushed Terry at close range during the terrorist war in Rhodesia. He survived unscathed and his dog was shot in the leg. Terry has since been widowed twice.

Our routine in the camp involved twice-daily roll calls on the parade ground. The guards searched our barracks about every fourteen days. It was surprising to see what trickled through from the camp guards. Things like petrol, alcohol, matches, radio parts, were obtained, and even equipment that prisoners subsequently used to dug tunnels with.

We cooked, ate, slept and passed the time from lock-up (5pm) until 8am. For the rest of the day we had to entertain ourselves. That was not easy! We played various kinds of sport, played card games like bridge, and read books. Most of us decided to make the most of our time as POWs as there was not much chance of escape. The Red Cross supplied us with food, cigarettes, sports equipment, educational requirements, and enough musical instruments to provide for an excellent camp orchestra.

Fortunately, we had a library and a good supply of books, (also supplied by the Red Cross). There were also a number of bands and an amateur drama club. Amongst the 10,000 prisoners in the camp there were many highly educated men, many of whom conducted lectures in their fields of expertise for the benefit of the other prisoners. I attended agricultural classes put on by a professor from the Illinois Agricultural University that were very informative. The worst thing was still the boredom because of our confinement. It wasn’t as bad for us in the summer as it was during the winter months when we were confined to our barracks for 24 hours a day (except for roll call).

Occasionally the air raid sirens sound their dismal warning and then far up in the sky we could see those beautiful silver bombers roaring on their way to Stralsund, Stettur, Koningsberg, or some other distant target on the Russian Front. How we long to be up there again! We follow with envious eyes the little specks that are the planes until they and their vapour trails disappear in the Eastern sky. Each and every one on us would at this moment willingly have risked our lives to be up there! In our minds we are handling those lovely controls, feeling the plane climb, dive, bank, and surge under the lightest touch of the fingers. We can hear the dull familiar roar of Merlin engines. These are the nostalgic feelings of vanquished airmen.

The Red Cross parcels were wonderful (when they managed to make it through). They contained such things as chocolate, cigarettes, and a lot of dehydrated foods, such as onions. On one occasion, when some Red Cross packages arrived and people in one of the barracks were cooking the onions, our sense of smell was so sensitive that prisoners could smell them over the whole camp.

Red Cross food and good news keeps us alive and keeps our spirits up. Arnheim was a tragedy, but Aix la Chapelle is in our hands and we realize that Gerry cannot last much longer. On October 18, we get the news that Rommel is dead. The Russians have broken into East Prussia and Checholovakia. Runstedt has made a brilliant drive into Holland, but we have our heroes like “Ike”

[Digital page 23]

and “Monty” who can take care of him. Our generals, Simpson, Patch, Patton, Dempsey, Hodges, are surely a match for any German general.

In the meantime, we prepare for the big Rugby match of the season, the Springboks versus the Anzacs. I captain the Springboks (South Africa) and we lose to the Anzacs (Australia/New Zealand), 6-5. Other Rhodesians on the team were F/lt Terry Fynn [Flight Lieutenant], and F/lt Cecil LeSueur [Flight Lieutenant]. In the final match of the season, British Empire versus British Isles, I captain the British Empire team and we win 11-6. Our star center is Wing Commander Billy Tacon, a New Zealander. “Butch” Thomas, New Zealand Schoolboy International plays at full back.

Winter is now at hand and we prepare to hibernate as best we can. We are sure the East and the West are going to bring off their winter offensives simultaneously, but as November passes into December we lose hope again. Sport is curtailed and the enthusiasm we had to attend lectures disappears. We pass the days playing chess and bridge, reading, gossiping, and speculating on the end of the war.

Our barrack-room cook was a Canadian called “Shorty” McCloud (only about five-foot-six), a gunner in the RAF (Canadian Air Force), I think. He was always hoarding food supplies and we never discovered where he hid it. However, on my birthday (October 29), he baked me a cake. He had been saving such things as prunes and raisins and by New Year he had saved enough to brew 2 1/2 bottles of alcohol for us. We all took part in this brewing, and we were saving some of our fuel (for the distillery fire). The piping was made from tins cut into strips and soldered into tubes. The pipe would run through a larger pipe. We then filled the larger pipe with snow from outside the barrack room.

The material used for soldering was gathered from the tops of Bully-beef tins. This had taken months of work but we had a great many experts there from whatever trade you could think. And so on New Year’s Eve we had a party. The Germans heard this and raided our room in addition to many other rooms. The outcome was that our salt ration was cut out completely, because we had been using salt to keep the snow in the right condition for distilling.

We have all saved up a little food, and together with the Red Cross parcels we have a really slap-up Christmas dinner. We have jealously guarded and save our prunes and we have made a rough-and-ready still, with which we have made a few bottles of gin. A few pounds of raisins and sugar help bring about fermentation, and the whole operation is a success. The conducting tube is made of little strips of KLIM tins soldered together to form a pipe – cooling is affected by a larger tube around this, filled with ice from the local pond.

Solder is obtained from the tops of thousands of “bully” beef tins. The amount of work this took! Downing is installed at the end of the tube, as official tester. His job is to see that not too much water is boiled off with the alcohol. The idea was sound, but unfortunately, “Happy” acquired a taste for the burning liquid, tested too often and had to be replaced. Brewing of alcohol is prohibited, so all these operations have to be carried on at night after lock-up. The Germans could never understand why there were so many happy “Kriegies” on Christmas Eve.

[Digital page 24]

For the first few months our food rations were fine, we were getting food supplies from the Red Cross in Switzerland. However, as the war dragged on and the allied armies began to cut the German supply lines, the routes for Red Cross relief from Switzerland through France and Germany were closed and our supplies began to dwindle. Supplies had to be re-routed through Sweden and this took a few months to be re-established. For a few months then, there was very little food. We subsisted on what the Germans could provide us. This was minimal as the German civilian population itself was virtually starving and got preference. The prisoners-of-war were left with whatever dregs of food remained such as cattle turnips (swedes) and rotten potatoes.

We were now on a starvation diet of less than 1000 calories a day, which would eventually kill us if it continued long enough (I weighed only 135 lbs at the end of my internment). A number of prisoners were hospitalized with diseases related to this slow starvation. Some of them died and a few of them went insane. The time period between November 1944 and the end of the war was a bad time for us.

January 1945. As yet, there are no signs of the forming winter ground offensive, but night after night, the Mosquitoes hammer away at Berlin, and the R.A.F’s offensive gathers momentum. “Bomber” Harris is in his full stride, thousands of tons of bombs drop on Germany every day, and the German newspapers take an almost pathetic view of the whole thing. The R.A.F. are called “terror-fliegers” and murderers and the German people think it is wrong and unjustified. They think that they should not be bombed. Every day the Roll-of-honour list in the Volkisher Beobachter (Peoples Observer) gets longer and longer. The rail link with Switzerland is cut and consequently we get no more Red Cross parcels. The R.A.F. bomb Steltin, Strahlsund, and Rostock, and the Germans cut the electricity to our barracks is to one hour a day. Our coal ration is cut so much that we can only have two fires a day to cook our food.

The icy blasts of the East (Russian) winds cut through us, and the temperature remains well below freezing. This is my first experience of snow. Although I like the look of it, under these conditions it does tend to become boring. German rations are cut to a few bad potatoes and turnips daily. We eat the potatoes skin and all to get every possible bit of nourishment from them. The turnips and swedes are a different matter. We have run out of salt completely and have to eat them cooked only in water. I swear, no matter what happens, I will never be able to face a turnip again without cursing. We occasionally get a little margarine, which we have with our black “ersatz” bread. The bread itself is not bad, if we could only have more of it.

The worst part of the whole experience at this time was the boredom and the desire to be free again. As time went on, hope built up. The Russian forces were getting nearer. We were well informed about the war because of our own radio receiving station which was, unbeknown to most of us, located in our own camp church. It was only after the war that we discovered the location. We had a daily war bulletin throughout the war (with the exception of a few days when German activity within the camp prevented this).

[Digital page 25]

Nobody, to my knowledge, escaped from our camp. The big escape (the “Great Escape”) was from Sagen? Stalagt Luft 3, which was in Poland. We were stationed Stalagt Luft 1 which was at Barth-Om-Ostsee on the Baltic Sea. Stalagt Luft 1 was located on a peninsula with very flat terrain, and only a few feet above sea level. A number of tunnels were attempted in the camp. As soon as the POWs dug down to sea level, however, the tunnels would collapse. So we could not escape in that way. A number of other escapes were also attempted. People tried to get out on laundry wagons, and that sort of thing, and few men were shot trying to escape, but none, to my knowledge ever got away. In the case of Sagen, 52 men were shot.

The hours seem to drag by more slowly and everybody is getting on everybody else’s nerves. We become morose. All we can think of is food, food, food. A few men have hoarded chocolate “D” bars during the flush period. Some of the more mercenary types are selling them for five pounds for a four-ounce slab. It is amazing that this could happen, but these shylocks willingly accept IOU’s [“I Owe You’s”] in the hope that they will survive and be able to cash in on them on their return to England. How pathetic it is to see grown men, officers, squabbling over a crust of bread!

Some are hit harder by the hunger than others. The young growing men feel it the worst. Some of them, 19 year-old, mere boys, are driven almost crazy. With the onset of malnutrition, all kinds of dormant diseases show up, first of all diarrhea, and then dysentery. The hospital is filled to overflowing, and our doctors and medical orderlies are overworked.

By January 1945, many POW camps in Poland and on the Polish border were evacuated and moved in order to in order to keep them out of the hands of the Russians. Thousands of allied prisoners were marched westwards by the Germans through heavy snow in bitterly cold conditions on the infamous “death-march”. These poor fellows underwent the severest trials under the stress of cold and hunger. Germans chained some of the POWs together in gangs, and in many cases the men were brutally beaten and, in some cases, shot on the slightest provocation. Some men eventually collapsed from exhaustion, and were left by the roadside to perish from hunger or from the cold. Frostbite took a heavy a toll and the Germans diverted a large number of these cases to Stalag Luft 1, as they passed close by to our camp.

The general feeling was that Hitler was doing his utmost to keep all POWs in Germany and that he might eventually, if all else failed, use them as hostages. We were also able to see what would happen to us if we were marched out in those conditions. That was not a very cheering thought! Some of the men brought to our camp died. In many cases gangrene had already set in, and men had to have limbs amputated.

The guards are now mainly “Volksturm”, or Home Guard. They are nearly all old men and boys. They are all, however, still capable of pulling a machine gun trigger. The youngsters are fanatical Nazis and their triggers fingers are “itchy”. The older men, some of them 70 years old, do their work with a sense of resignation and hopelessness. One of these old graybeards told us that he was too old to be called up for World War I. The Wehrmagt [Nazi Armed Forces: “Wehrmacht”] seems to have lost more men than it cares to admit.

[Digital page 26]

In February I go down with dysentery and spend 10 days in hospital. In the bed next to me is an American Lieutenant (I forget his name). He was flying a Fortress, and was shot down over Lake Platten in the summer of 1944. His is one of the most amazing stories I have ever heard. His aircraft was hit by flak over Czechoslovakia, it caught fire, and he bailed out and landed about three miles from the shoreline in Lake Flatten. Fortunately the water was only about five feet deep, and so he was able to wade toward shore. By this time it was dark, however, and he found himself in amongst a maze of thick reeds, in three to four feet of water.

During the night he waded around without finding the shore and by morning, was completely lost. He had to keep quiet and not move during the day, and at night, he again tried to reach the shore. After the third day, he had consumed all of his emergency rations. On the 4th day, he tried to drink some of the polluted water, but it upset his stomach. After this he went off his mind. On the day two men found him; he was lying in about a foot of water, too exhausted to even to crawl. The instinct of self-preservation had made him gather some reeds under his head to keep it above water. A Czech doctor took charge of him, and he regained consciousness after two weeks.

He was six-foot-two and weighed 190 pounds before his ordeal, and now weighed only 97 pounds. His flesh had rotted away with gangrene, and most of his toes had to be amputated. A lot of flesh had to be removed from his feet and legs. In March of 1945, he weighed 140 pounds. Now he is a broken man, both physically and mentally. He suffered frequent attacks of hysteria. His ordeal is an amazing example of what physical test the human body can endure.

The war had by this time become more or less static. Early in the New Year the Russians began to advance again towards the west. The American and Allied air forces were continuously raiding the area to the East of us, places like the ports of Stetin and Rostok. The bombers often flew over us. When that happened we were subjected to air raid precautions. As soon as the sirens sounded we all had to go into our rooms, and the barracks were locked up tight.

On one case, on Easter Sunday of 1945, the air raids started at about 10 o’clock in the morning and carried on most of the day. We were locked up in our barracks. A number of POWs who happened to stray from their barrack rooms during these curfews were shot, some fatally. A friend of mine, George Whitehouse was shot when he was trying to get some sand outside his barrack room window. He needed the sand because we used sand to clean our pots. He was the duty orderly for his barracks that day. Fortunately he survived, but he spent weeks in the hospital as one of his kidneys was destroyed.

The German guards were quite callous in that respect. They were strict. When they issued an order and the order was transgressed in any way, they had no hesitation in using their firearms to enforce it. Easter Sunday was a particularly bad day for the Germans because of the number of air raids in that area. A number of prisoners were shot or wounded. The guard dogs that were now patrolling inside the wire mauled several POWs. Nevertheless, it was an exciting time for us.

[Digital page 27]

LIBERATED

We got to see our own bombers flying overhead and we heard the Russian bombardment of the German positions getting closer every night. The guards seemed to be getting more nervous every day. By the beginning of May they started trying to make friends with us. On the second or third of May we woke up to the fact that our guards were all gone and our own people took over the prison camp. The Russian army had by-passed us during the night and were heading west and then south in a pincer movement. None of us quite knew what was happening and we were in quite a nervous state. By this time we were all in poor physical state. There were a lot of people in hospital with dysentery and psychological problems (nervous/anxiety attacks). Each prisoner was allowed to go with their representatives to the administrative offices where the so-called “criminal records” of the POWs were kept. There was a complete prisoner docket with the photograph with front and side profiles and all your other particulars. I managed to get the full sized and another smaller one and a few cameras and an SS officer’s dagger and brought them home. Two or three days later we were finally allowed out of camp.

We were taken to a nearby German air base were they had started turning out the first of the jet fighters. We had seen these frightening planes flying over the camp. The fighter was called a Henchel 123. We also had to help clean up a concentration camp that held mainly Greeks and Romanians. They were used as forced labor for the factory. It was a shocking place. It was our first sight of people dressed in the “striped pajama” uniforms of the concentration camps. The local German population was also rounded up and the men and women were forced to do the dirty work.

[Digital page 28]

[Scanned record and photograph with caption] The POW “docket”

A friend and I decided we had seen enough of Germany. We “liberated” a couple of bicycles and started to cycle west towards Wiesmal. A couple of days later we arrived there and were picked up by an American jeep. The Canadian and British forces had met up with the Russians and that was the end of the war in that part. We were taken in a convoy of army buses to Brussels. The journey took a couple of days and from Brussels we were flown to England and arrived there on about the 10th of May. In England we were deloused. We went on to Rhodesia House in London

[Digital page 29]

and got some goodies like chocolates and cigarettes and waited for our return to Rhodesia. In my case I spent until July at Brighton Hoge on the coast of Sussex.

A party of us were invited to a tea party at Buckingham Palace. We met the King and Queen and the two young princesses. It was a very informal “do” They just wandered amongst us and talked to us. We were all ex prisoners-of-war and mostly Rhodesians. Our own embassy arranged it. The Queen wandered around with Princess Elizabeth and the King with Princess Margaret. They talked for a few minutes with a group of a half dozen of us. I jokingly asked them “when are you coming to see us?” Princess Margaret replied “oh, next year.” When the queen walked off, the journalists surrounded us and wanted to know exactly what had been said. We told them what Margaret had said, and couple of days later the South African newspapers were reporting that the King and the Royal party would be visiting South Africa and Rhodesia the following year. That was the first anyone had known about it. It was a very pleasant interlude and something you remember for the rest of your life. We also obtained a number of photographs taken of us at Buckingham Palace gates and in the tea garden.

[Photograph with caption] RAF pilots meet the Queen (Princess Margaret at left)

I managed to get a seat on a flight with the RAF from London to Brindisi in Italy. From Brindisi I flew with some of the other returning servicemen to Cairo in the bomb bays of a “Liberator”

[Digital page 30]

bomber. From Cairo we flew to Kisumu in Kenya and then to Bulawayo in Rhodesia in a DC3 “Dakota” (the seats were taken out and they crammed in twice as many passengers as they normally carry), I took a train to Salisbury and was met there by my parents.

The war in the East (with Japan) was continuing. Some friends and I volunteered to go to the Far East to fight. We were given two months leave, but in August the atom bomb was dropped and that ended the war. We were notified that we would be granted two months paid leave and then we would be retired from the RAF.

In the meantime I started working on the family farm. I then got a job on a tobacco section of Abercom Ranch. My father’s health was failing, however, and I went back to his farm again at the end of the year. I had applied for a Land Settlement Board farm and so I had to do the required training (which I did on the farm next door). The land settlement ex-servicemen’s scheme provided grants for those who wanted to go into farming.

While I was doing my training, I applied to attend to Sadara agricultural college in South Africa. At the same also I saw an advertisement in the agricultural press by the Nuffield foundation, offering scholarships for young Rhodesian farmers. On a whim, I applied for that as well. During the same eventful week, I was accepted by Sadara College and awarded the Nuffield scholarship to go to Britain for 6 months. Fortunately for me, I decided to accept the Nuffield scholarship first, and go to England. I arrived in England in December 21st, 1947.

They placed me on Pressen farm in Northumberland. My host was John Barr, a respected and very good farmer. During the first week there, I met the neighbor’s daughter. Daphne Brown, who I subsequently married. I spent six months in Britain (until June 1948), and Daphne and I were engaged Just before I returned to Rhodesia.

[Digital page 31]

[Photograph with caption] Jack and Daphne are married, 1949

When I returned to Rhodesia I applied for, and was allocated, a farm in the Fort Victoria district. Daphne and I called the farm “Flodden.” We were eventually married in February 1949, just after her 21st birthday. I brought my bride home to a 2-room “pole-and-dagga” (pole and mud) hut.

[Digital page 32]

[Photograph with caption] Daphne and Chris on Khartoum Farm

It was a pretty rude awakening for her! Nevertheless here we are, 49 years later, still happy with four children and ten grandchildren. We left Fort Victoria the following year because of the arid farming conditions. We got a farm in the Hartley district where we farmed for 38 years. Then the government took the farm over from us for resettlement of peasant farmers. And we bought the farms where we now live.

Acknowledgements

There are numerous photographs of the camp and the barracks that can be seen at a POW website on the internet (URL) [Link broken, 2018].