Summary

This text describes Stephen Williams escape from Villa Orsini, starting in Sulmona, on the run and through to near Casoli. They had planned throughout their time in the Villa for an escape, the guards focused on their own awkward predicament of possible relocation from home by the Germans, even managing to get word to another POW camp that such an event was to occur, and led their escape into the mountains where they are aided by many Italian families and guides.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

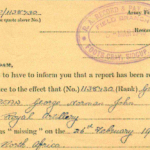

[Digital page 1]

Brigadier Stephen Williams in account by Brigadier A.A. Anderson in Villa. Orsini in Sulmona and then on the run and through near Casoli.

Captured in Tobruk this manuscript gives a good account of life in Villa Orsini and then living in the mountains with contadini, clothed, fed and hidden by them.

Relates that General Klopper was allowed to phone to main camp at Sulmona and he told them to get out (Main camp. 4 miles away?). They get out (after a year) and a family near Petterano feeds them and others for 3 months. They split up and move westwards. Hide in caves until is a rastrellamento. On the run at Christmas. Helped and hidden with charcoal burners – with their families. Helped with money and clothes from Vatican, (The Rome Network). They have four alternatives, a) dash over the Miella. b) Adriatic coast and boat, c) By train north and then out through Switzerland, d) Vatican. While waiting at one point, their footsteps around the barn are masked, by the Italians driving sheep around. At Christmas they leave with guides. Some depart to get through lines with guides and; it is agreed that if they get through they should arrange for certain flares to be dropped when Sulmona station is next bombed. The next raid, there are no flares but then a lone plane follows and drops the flares to show they had got through, and that the guides were on way back. After the guides return some 35 set off. After Campo di Giove they make for the pass in the snow. They get over the Sangro and go through evacuated villages of Lettopalena and Aranto Palena About 15 of them split up into pairs and aimed for a rendezvous on the Casoli road. They sent the Italians ahead and then a jeep appear and a three tonne lorry to pick them up.

Besides being one of the few accounts ending up at Casoli this gives good description of Villa Orsini, and uniquely how sheep are used to mask their footsteps in the snow and, most importantly it is the only account remembered in which those who got through were able to send by plane and flares a message to those who followed.

[Digital page 2, original page 53]

[Text overwritten] Written by Brigadier Anderson

Brigadier Stephen Williams D.S.O, Royal Horse Artillery and C.R.A. 7th Armoured Division: His Capture and Escape.

On 27th May 1942 the Axis forces launched an offensive in the Western desert with the primary object of recapturing Tobruk. The main attack consisted of an encircling movement round the southern flank of the British position (Gazala Line).

The 3rd Indian Motor Brigade bore the brunt of the initial assault and were overrun. The enemy armoured forces then joined battle with the 7th Armoured Division during which at least a part of the Divisional H.Q. was overrun resulting in the capture of the G.O.C. [Ground Observer Corps] (Maj Gen F Messervy) and his C.R.A. [Commander Royal Artillery] Brigadier Stephen Williams); the G.O.C who had been able to conceal his identity made good his escape but the unfortunate C.R.A was soon recognised as a senior officer and whisked to the rear and eventually to Italy. In the subsequent fighting during which Tubrek fell and the Allies withdrew to El Alamein, ten more senior officers (6 from Tobruk) were captured and by devious routes were taken to Italy as prisoners of war, all being accommodated in the Villa Orsini.

The Villa Orsini situated on the outskirts of the town of Sulmona which lies in a broad valley in the Apennine mountains to the southeast of Rome was used as a P.O.W [Prisoner of War] camp for Generals as all officers of the rank of Brigadier and upwards were called by the Italians.

I (captured at Tobruk) was the last to arrive at the Villa where I found already in residence:- Major General H Klopper, South African, Brig A Hayton, South African, Brig F Cooper, South African, Brig C Boucher, Indian Army, Brig D Reid, Indian Army, Brig G Johnson, Guards; Brig W O’Donnell, R.T.C [Returned To Corps]; Brig L Thompson, R.A; Brig C Valentin, R.A [Royal Artillery]; Brig S Williams, R.A. with ten other ranks acting as house staff and batmen.

The villa, a three story house with about 12 bedrooms, stood in a small but compact garden on the edge of a copse, the whole estate not more than an acre and a half was surrounded by a barbed wire fence with armed sentries patrolling outside, by day. At night all P.O.Ws were locked in the house with ground floor windows shuttered and barred when the sentries patrol around the house, inside the wire.

Our meals prepared by British P.O.W cooks would have been skimpy had we not been able to supplement our rations with food from Red Cross food parcels. Briefly the daily routine was:

Exercise; walking round the grounds, five times round the house and grounds equalled one mile.

Games: tennis quoits, the only outdoor game we had room for.

Work: self imposed tasks in the garden; Stephen usually employed himself looking after roses and growing ‘Morning Glory’ up every plant and tree he could find.

[Digital page 3, original page 54]

Walks: once a week we went out into the country in two parties with an armed escort, for a recreational walk, known as the ‘Fast convoy’ and the ‘Slow convoy’. Stephen joined the slow pack, he preferred to stroll and take notice of the lie of the land against the time when we would escape.

In wet weather: we danced Highland reels in the hall to music from a piano hired at a fabulous cost. The pianist was Walter O’Donnell, the instructors the Scots (we had two) of the party.

All this seems very jolly, it was, but the real object was to keep fit against the day we would break out.

When locked in after sundown we either retired to our bedrooms to read or write or join in a game of Bridge or in a special game of cards invented by Stephen, a variation of ‘Rummy’ called Sulmona, a noisy game which frequently annoyed the Bridge players. As Stephen was continually making new rules we never mastered it.

We had frequent meetings in someone’s bedroom making plans for escape when the time was ripe. The usual method of escape from P.O.W camps is tunnelling but as the villa was built on gravel tunnelling was unpractical.

Every 2nd Sunday we had a non-denominational Church service taken by a Methodist Padré from the main camp, known as Campo 78, about four miles away. We used him to convey forbidden messages to the P.O.W there about escape plans etc. Stephen was the main culprit in this respect.

For the next twelve months we managed to live in harmony.

News from the outside world was scarce, we were only allowed Italian newspapers as approved by the Italian authorities, and Items of War news prepared for home consumption, this meant that we received news favourable to the Axis forces at once but news of Allied victories was usually released a week or ten days after the event and then in the form of ‘Axis forces withdrew to … in accordance with plan’. In time we became quite expert in appreciating the situation, for instance, on 25th July we learned that Mussolini had been succeeded by Marshal Badoglio as Prime Minister, and by the middle of August we gleaned that Sicily had been occupied by the Allies and on 9th September the Allies had landed on the Italian mainland.

By this time all P.O.W south of Sulmona had been taken away to the North of Italy and our guards were becoming jittery lest we should also be taken away perhaps to Germany with the chance that they also would have to accompany us; this was the last thing they wanted for their homes were in the district so from now on they became friendly and cooperative.

We now began making plans to avoid being surprised and prepared to break out. We cut gaps in the wire at the back of the house through which we would bolt as the Germans came in at the front. Our guards made no attempt to stop us but sentries were placed on the gaps to prevent anyone going out.

Our country walks had been stopped; we now approached the

[Digital page 4, original page 55]

Commandant and asked if we could go out in parties with escorts; our object to prevent being surprised, he agreed, so we went in syndicates, my syndicate consisted of: Brig C Valentin and batmen Cpl Snelling of the R.T.C.:

Brig S Williams and his batmen Bombardier May of the R.A. and myself, my batman being a South African went out with Gen Klopper. After a good afternoon wandering in the orchards having a good stuff on apples we returned to a pre-arranged rendezvous where we met the interpreter who informed us that the Germans had been at Campo 78 to say they would return next day with motor transport to remove all P.O.W; no mention was made of the Villa Orsini but we expected we would be taken also.

We had a night’s grace, so returning to the Villa we immediately decided to warn Campo 78 and then make away into the country ourselves.

We could see the Italians were also preparing to move but where to, we knew not.

Whilst we prepared, each person taking what change of clothing he required and could comfortably carry, leaving the bulk of our possessions behind, sharing out rations, each person carrying one Red Cross food parcel as far as they would go round, collecting chocolate which had accumulated and cigarettes for the smokers, filling water bottles etc. General Klopper asked if he could speak to a South Africa friend at Campo 78 on the phone, such a thing in the past had been absolutely forbidden, he was allowed to do so, speaking in Afrikaans, the second language of the Union of South Africa, English of course being the first. He warned the camp of what was going to happen. That night, I have been told, 2000 young officers and men, taking advantage of the jittery condition of their guards, made off into the hills. Some escaped to British lines but unfortunately the majority were recaptured when out in search of food.

In the meantime we once again sallied forth still keeping to the same syndicates, our armed escorts with puzzled looks accompanying us. We made for the west side of the valley away from the milling crowds of escaped prisoners for whom we suspected search parties would be hunting. At last we were at large.

For three days we lay up, sleeping in a different place each night, meeting at an arranged meeting place to exchange news and share out food. When we were told our escort the truth, they obtained mufti from the village, left their rifles and ammunition and deserted.

At last we decided to disperse. Klopper’s syndicate, all South Africans, set off first in a southerly direction; our syndicate followed keeping to the higher tracks. Our object being to get close [text illegible]

[Digital page 5, original page 56]

advancing up the coast, this of course was wishful thinking; however, whether we were doing the right thing or not, it was definitely wrong to do nothing.

Our first days march took us to the vicinity of the village of Petterano; here we were accosted by a youth helping an elderly man in the fields. As we were still in uniform there was no mistaking our identity as British. The youth had been an Italian cavalry soldier whose regiment had disbanded itself when the Italians surrendered; he suggested that we should rest in the woods and he would bring food to use the next day. This we did, building shelters with branches; the weather was still warm.

Next day the youth, who became known to us as ‘Sebastiano’, and an elderly man with the name ‘Luca Agapeti’ with his two student sons who could speak a little English, appeared with a meal of hot spaghetti and brown bread. The elderly man who was a notable of the village informed us that the ‘Americano’ were advancing rapidly and suggested we remain there until they arrived; he would provide us with food daily, Sebastiano acting as orderly. It seemed that the Italians, like ourselves, were thinking wishfully, at any rate he knew we were on the winning side and no doubt wanted to produce three Brigadiers out of the hat when the Allies arrived, with advantages to himself perhaps. We decided to wait for a few days then review the situation and if necessary continue on our way. Our motto at the moment was Security First. Luca and his family proved to be true friends and actually provided food for us and others for three months, for which they were in due course rewarded.

As the days passed and there was no change in the news and the weather ‘broke’, we moved to a cave in which we were nearly surprised by a German search party. Word had got around that three Generals were in the vicinity. Luca’s sons came to our rescue once more and guided us to a better and more secure cave. Unknown to us at the time, the Allies were not advancing as rapidly as reported; they had to fight every inch of the way. We were becoming so unsettled, we decided to move on once more, splitting up into two parties for the next part of the journey, each party to be accompanied by an Italian guide – not so much to act as a guide but to procure food on the way.

Brigadier Claud Valentin and Cpl. Snelling, with one Italian making up the first party. Stephen and Ddr. Hay with one Italian making up the second part, with myself odd man out to choose either. For various reasons I chose to throw in my lot with Stephen and Hay.

When the day came Claud and his party were given a great send off, their route lay along the ‘La Meta’ mountains keeping south of Cassino, the site of some severe fighting later in the war. Stephen and I and Hay proposed following the same route 48 hours later; little did we know it at the time but this was the last we were to see of Claud and Cpl Snelling. The evening before Stephen and I were due to go, Claud’s guide returned saying they had been ambushed and the party had split up. It later transpired that they got away and eventually reached Allied lines. The news proved to be too

[Digital page 6, original page 57]

much for our guide, who called off. We had no option but to delay our start and look for another guide.

Now a real disaster befell us. Snow came early on the mountains making it necessary for us to reconnoitre a new route on lower ground, or wait for a thaw or hard frost.

During this we contacted many escaped P.O.W trying their luck southwards, few of whom were successful. A Captain Lawrence visited us from an adjoining valley saying he had plans and guides, would we join him in an attempt to get through.

Under the prevailing conditions Stephen would not tackle the journey but urged me to have a go whilst Hay remained with his Brigadier. I fear that at this time his legs were giving a little trouble. Sufficient to say my attempt was an abortive one. We ran into the Germans and had to retrace our steps and needless to say I was welcomed back. Lawrence returned to his own valley.

Instead of frost we had more and more snow making a trek through the mountains out of the question for the time being.

German search parties were becoming more active. We heard from our Italian friends that a price of 40,000 lire had been put on our heads and that the Germans wanted to clear the area before Christmas so that they could relax during the festive period. On receipt of this alarming news we moved further up the hill to a new hide-out. Stephen sleeping in one cave and Hay and I occupying another by night. One day I roused rather earlier than usual and on looking down the valley was alarmed to see a whole company of Germans being led by an Italian civilian, no doubt a fascist, moving towards Stephen’s cave. Before I could do anything Stephen himself appeared; like me he had roused early that morning and escaped capture by minutes. It seemed that our daily excursions to perform our morning ablutions at the mountain springs had been detected by some Fascist Italian, who, on hearing that a price had been placed on our heads by the Germans, had been tempted to give us away and get the reward. The Germans now started searching the valley and woods, firing their tommy guns into the undergrowth as they approached. The firing warned us of their movements so we had no great difficulty in dodging them; they had not located my cave so from that time we all scrummed down in the one small cave.

Next day Luca arrived in a very alarmed state saying that he had been accused of harbouring escaped prisoners and that in future he would be watched. It seemed we had enemies in Petterano and would have to move out of the valley, if only for the sake of our providers.

Luca agreed to provide us with bulk rations for about a week, when we did move. As Christmas was upon us we decided to take a risk and wait until Boxing Day before moving further north into another very nice valley where Sebastiano had relatives who would supply us with food. We gambled on the Germans pulling in their patrols and leaving us in peace over Christmas.

On Christmas Day, Luca and the whole of his family, paid us a visit bringing with them our Christmas fare: hot spaghetti,

[Digital page 7, original page 58]

fruit and a flagon of Vino. Next day we set out for another trek over the mountains, each carrying a sack into which we had stuffed our blanket and greatcoat and other small kit we had accumulated. Although we were now dressed in civilian clothes supplied by Luca and friends from the village, we had retained our military greatcoats. On our way we stopped with a family of wood cutters and charcoal burners who were living in the woods and shared their hut for the night.

That night we slept eleven in a bed. The bed consisted of a platform of branches running right round the hut, the men folk sleeping on one side, the women on the other. After a jolly evening we kicked off our boots and wrapped ourselves in a blanket, not to sleep I am afraid, for the ‘fug’ cannot be described. Needless to say we were up with the lark in the morning and although pressed to stay we declined with thanks and got going, picking up Captain Lawrence and a companion on the way.

As we increased height, we found the snow becoming deeper and deeper and without realising we gradually side slipped into another valley where we rested for a time in a hut. Lawrence, who could speak Italian, gathered from peasants that two P.O.W. were living in an empty house just over the crest from where we were resting; breaking up into pairs so as not to be too conspicuous we made our way to the house to be welcomed by two R.A.F Sergeants.

Having been given an assurance by the owner of the house who was a fanatical Roman Catholic, that we could stay as long as he didn’t get into trouble, we set about trying to appreciate the situation and make plans all over again.

Stephen was now his old cheerful self again; he, like all of us, had been in the dumps for a time. We didn’t like living out of doors in the snow or dripping on by water when asleep, for the caves were leaky places. We gathered from our new companions that there had been one or two organisations operating for the welfare of escaped P.O.Ws. For instance, local farmers, in the pay of the British authorities, with an intimate knowledge of the country, had been taking parties across the Miella range of mountains to the British lines.

There was also a rumour that British Motor Torpedo boats had been visiting the Adriatic coast picking up P.O.Ws.

Another organisation appeared to have been working from the Vatican City looking after the welfare of escaped prisoners, but not helping them to escape. We also heard that some had been given sanctuary in the Vatican. From this source we obtained some under-clothing and money; Stephen got 1800 lire I had already received 1400 lire from Luca Agapeti. So between us we could muster 3200 lire, all in notes. We both felt quite affluent. This, according to the current rate of exchange was a very small sum indeed, but to an Italian peasant it was a small fortune.

We were also given the address of an Italian living in a

[Digital page 8, original page 59]

village near Varese in northern Italy, who for a substantial reward would smuggle prisoners over the frontier into Switzerland.

By going south in an attempt to break through the German lines, we had missed all this. We appreciated we had four courses open to us:-

First. A dash over the Miella range of mountains, not a long journey but a hazardous one for a 5000 feet pass covered in snow, patrolled by German Ski troops by day, had to be crossed by night. However we had the satisfaction of knowing that some had already made the journey successfully.

Secondly. To make for the Adriatic coast and try to get out by sea. We had been told that a Lieut. Colonel had escaped this way in a fishing boat. We could not hope that the M.T.Bs [Motor Torpedo Boats] were still operating.

Thirdly. Travel by rail to northern Italy in an attempt to get into Switzerland.

Fourthly. Try for an entry to the Vatican City.

Stephen was all for the second course: we had the money and he hoped to hire a fishing boat and induce the owner to accompany us and when we reach British territory to hand the boat back with a suitable reward.

Hay and I were in favour of the first course when weather was favourable; Hay had always advocated taking this course even from the start.

We came to a compromise: we would wait and see what the weather would do. If it did not improve soon we agreed to accompany Stephen to the coast.

We had another fall of snow and I think the following is worthy of mention. The farmers were alarmed lest our footprints in the fresh snow would draw attention to the fact that a supposedly empty building was occupied. To counteract this a flock of sheep, taken from their winter quarters, were driven around the house and up and down the lanes and paths obliterating footprints and beating down fresh snow so that we could get out and take our exercise, and just as well for no sooner had this been done than a party of German soldiers arrived looking for forage for their mules. We saw them coming and took cover: Stephen and I crouched in a disused pigsty, whilst the others rushed upstairs into a loft and burrowed under the hay. The Germans, after peering into the windows went off to the owner and ordered him to deliver a quantity of hay. This was just another incident.

This German activity hurried arrangements for another trip in which Stephen though the going not good enough yet. However, Bdr Hay and Lawrence’s companion, a Corporal of the R.E., decided to have a go with our blessing. Before they moved off, Hay was given a verbal message the gist of which was: ‘That as soon as conditions improved another party would make an attempt and to ask that on the next bombing raid on the Sulmona railway our aircraft should fire a succession of red verey lights to show that the party had got through, but if the guides were returning to drop three white parachute flares’. A forlorn hope’ we did not think that this would be done. We would wait for one week before expecting any signal.

[Digital page 9, original page 60]

In the meantime Stephen, Lawrence and I moved to another more remote house. We thought it was unfair to draw attention to the R.A.F Sgts billet; we promised to let the Sgts in on our next attempt.

For about a week there was no air activity until one day we heard the now familiar sound of Allied heavy bombers. Rushing out we scanned the sky and there circling overhead was a flight of heavy bombers. After dropping their load they made off home-wards without making a signal. We returned to our billet a little disappointed but soon we heard another familiar sound. This time of a single aircraft. Out we rushed again and there circling overhead and gradually coming down was an obvious British Aircraft. When over the valley the pilot dropped three white parachute flares. This was the signal to say the message had been received and that the guides were returning. From that moment Stephen gave up all ideas of the Adriatic move and became the most enthusiastic for a dash over the mountains. We immediately set about reconnoitering the quickest route out of the valley by night. We were prepared to go with our farmer friends who knew the pass even if the guides failed to return. However, in a day or two the guides did return, bringing with them a package and a letter which read:

To B, A, of C.

B, w, of 7.

Herewith some of the needful plenty more here but come and fetch it, these men are to be trusted.

(signed) ? “A” Force.

Or words to that effect, which meant:

To Brig. Anderson of Cameroons.

Brig. Williams of 7th Armd Div.

The needful being, one bottle of embrocation for Stephen’s legs and my back. One tin of Keating’s powder, not required. One packet of Cape to Cairo Rhodesian brand cigarettes, and a bottle of Rum which we immediately tapped and drank amidst much spluttering to the success of the next venture.

Stephen kept the letter, although I coveted it.

It was all we could do to prevent Stephen setting off at once. The guides wanted to rest; they also wanted to collect any other P.O.Ws in the neighbourhood, for every additional head meant a bigger reward. We also had heard that a number of young Italians wanted to make the trip with the intention of joining up with the Italian Partisans operating with the Allied forces.

We decided at once that there should be two parties for it wasn’t right that a successful attempt should be prejudiced by one or two crooks.

The first party would move off on Saturday evening, and the second (our party) to follow on the Sunday evening approaching the pass from different directions so that if one was intercepted it would not prejudice the success of the other. On the Saturday a composite party of British, or more correctly Allied P.O.W for I believe one of two Checks joined and

[Digital page 10, original page 61]

Italians, 35 strong set off. On the Sunday we assembled at a farmer’s house for a meal before setting out. The meal consisted of seven courses of mutton, each done in a different way – or so it seemed, with lots of Vino. Whilst there we had still another scare: a very young German soldier came to the door and asked for a drink. I wonder what he would have done if he had known that five of the people in the house were escaped prisoners of war!

At dusk we set off in pairs to a rendezvous on the Petterano road, a mule following with our food etc. One amusing incident helped to cheer us on our way: following a sunken track we had to pass under a bridge on top of which were two German soldiers having a conversation, maybe waiting for their sweethearts. We liked to think that our disguise was so perfect, their curiosity was not aroused.

At the rendezvous, after dodging a long enemy motor convoy, we off-loaded our rations and sent the mule home. Our first hill was so strenuous we nearly gave up for the snow was deeper and softer than we had anticipated. Changing our route and keeping to the higher ground we found frozen snow which made the going much easier. About midnight we found ourselves in the outskirts of a village called Campo de Jovah which we had heard was a German billet. We had missed our way so we hurriedly beat a retreat and soon found the track: in doing so we bumped into a party of young Italians, all friends of our guides following our tracks, very sternly ordered them to follow on at a safe distance but on no account to join up.

All these little incidents were meant a waste of time. We had hoped to pass over the mountain by night; the snow was proving to be some help, it kept the night light enough for us to see our way, so as to avoid German patrols; now we couldn’t do it so we had no option but to lie up in a concealed area during daylight. We selected a scraggly copse and settled down on snow-free spots under shady trees. Fortunately the sun was soon up, so removing our boots and stripping off our sodden socks we hung them on the branches of the tree to dry and tried to get some sleep.

All that day we could hear the sound of German machine guns firing, probably practice for we were nowhere near the fighting yet.

At 4pm we decided to take a risk and press on in daylight so as to make sure of recognising the pass over the mountain before darkness fell. All went well until we reached a disused railway line along which the sound of a trolley was heard coming towards us: we had no sooner taken cover in a hollow before a railway bogie crowded with Germans rushed past us. It was the patrols returning to their billets.

We think we escaped notice but in case we had been seen we decided to press on through another scraggly copse, a short cut we thought, but by doing so we missed the pass. As the track, by now well beaten, zig-zagged up the slope there was nothing for it but to climb straight up knowing that we would connect with it higher up, at least so the guides said and how

[Digital page 11, original page 62]

right they were. After about a 200 ft climb, sheer upwards, we reached the track and from then onwards the climb was comparatively easy. Late in the night we reached the highest point on the pass, from now onwards it would be downhill. A halt was called and out came the brandy bottles, a good gulp each kept the cold out for it was freezing hard and some of us were only lightly clad. The halt rather upset Stephen, whose leg muscles began to stiffen; however a big burly Italian kept by him to give help over the rough spots. If one fell out here, all would have to fall out, so we were prepared to carry if necessary. Soon we reached the snow-line; on the Adriatic side of the mountains there was no snow on the low lying ground so that to the north the Germans were living in snow whilst on the south the Allies were living in mud. At the foot of the hill we had another longish halt whilst the guides went off to fill water bottles and to contact friends who gave them news that the German patrols had gone in except one machine gun post watching a bridge over the river Sangro, over which we had to cross. The river, having very steep banks at this point, caused us to slither down into the water and we had to wade under the bridge; the sound of the rushing water hid our stumbling noises for we were getting very tired, until we came to a spot where we could scramble up the other side; by so doing we dodged the German picket.

We still had about 8 miles to go and only two hours of darkness left; We were now making for the town of Casoli in the British lines but had to pass through or circle round two evacuated villages, Lettopalena and Taranto Palena; the first was deserted but in the second fires could be seen burning. They turned out to be Italians who had been evacuated by the Germans, back collecting their possessions. We joined on to the rear of one of the parties making for me coast, but their progress was so slow we broke away and made off across country. We were now in ’No Man’s Land’.

As it got lighter the Italians wanted to lie up and go in after dark, but we decided to continue; if we should stiffen up now we might never get going again – our feet were swollen and if we had taken off our boots perhaps we would not have been able to get them on again.

After a short rest and our last meal of ‘Sheep’s milk cheese’ and the last of the brandy, we went on across country. When the sun was well up, I cannot remember the time, we heard the sound of machine gun fire coming from the other side of the river. The young Italians, having now joined up, our party was about 15 strong, and it was at this mass of people making their way towards the Allied country that had attracted the attention of the Germans; the firing was meant for us, for soon another burst sent bullets screaming overhead – some came rather close, but they were rotten shots for no one was hit. The order went round to split into pairs and make their way independently to a rendezvous on the Casoli road which we estimated was about one mile ahead. I set out with one guide and Stephen with the other, the remainder following at intervals. In about half an hour we reached the road and in an hour everyone reassembled. We met here two Italians

[Digital page 12, original page 62a]

Partisans who informed us that the first party had been successful and that we had been expected to come in at first light, but now the patrols had gone back.

As we did not want to take the risk of being shot up by our own people or wander on to British minefields we sent the Italian Partisans on ahead to tell the British we were on the way. Soon a Jeep car with a very young and very suspicious British Officer with an armed party arrived followed by a three-ton lorry. Stephen and I scrambled onto the Jeep, the remainder climbing onto the lorry which was then driven Into the 70th British Division lines. From now on it was a case of being interrogated, medically examined and fitted out with uniform, whilst waiting for a leave passage.

It was the 25th January 1944, For approximately four months we had been at large behind enemy lines, most of the time snowed in, but at last we were free.

Brigadier Anderson. A.A.