Summary

John Muir was sent to the frontier between Egypt & Libya and was involved in Operation “Brevity”, which was successful in capturing Fort Capuzzo. Muir was then captured during a German counter-attack. He was involved in various escape attempts up until the Italian Armistice but none was successful.

After the Italian Armistice, whilst being transported back to Germany he and a fellow prisoner, Hugh Baker, escape from the wooden waggons of the train. Hugh Baker is injured jumping from the train and they spent time recuperating with the help from Italian civilians around a village called Avio. The rest of John Muir’s account is of their successful escape through the countryside and mountains of Italy into Switzerland.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

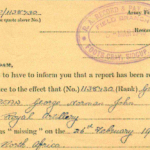

[Digital Page 1]

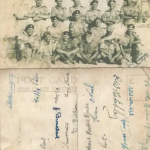

[Handwritten notes] John Muir Glasgow, D.L.I. [Durham Light Infantry]. Brief account in letter form. And ‘Times’ Article Dec 1945 on Gavi P.O.W. Camp. [Note: This article cannot be published on the website due to copyright but it remains in the original file in the Trust’s archives].

[Handwritten notes end]

John Muir and the Gavi Camp.

Commissioned in 1940 John Muir was in Wavell’s advance 40/41, in the siege of Tobruk and later in the recapture of Fort Capuzzo and its airfield but was wounded and captured in the counter attack. First in Razanella he was moved to Sulmona and then up to the Italian ‘Colditz’ – the very solid castle at Gavi, north of Genoa which housed such prisoners as David Stirling. No one escaped from there and when the Germans found so many POWs were missing when wanting to take them to Germany searched with a tooth-comb (in one report in the form of hand-grenades) and flushed them out. With the help of a small hacksaw Muir and Hugh Baker (Doughy) jumped the train east of Lake Garda. As Hugh had landed badly they holed up until 5th October but got into Switzerland on 12th October. Besides requesting a ‘Deed of Covenant’ to make his contributions to the Trust tax free he sent a copy of a long article on Gavi, which had been published in ‘The Times’ on 14th December 1945. Excellent material for the rapidly expanding archives.

[Digital Page 2]

JOHN MUIR. Lt [Lieutenant] in D.L.I. [Durham Light Infantry]

With 7th Armoured in Wavell’s sweeping victories. Captured near Fort Capuzzo on Rommel’s return journey. After 3 weeks moved via Naples to PG17 Rezzanello near Piacenza then to Sulmona. Started tunnel in toilet area but Muir caught at tunnel face when Itis discover tunnel. Shortly after transferred to PADULA. Then to punishment camp at Gavi – Colditz of Italy. After awaiting for the unsuccessful escape by others Muir and starts scheme near toilet area but the Italian Armistice comes and they use area they had found to hide from Germans but the G’s had found plan of Gavi fort and tracked down the far from empty space in which many were hiding. With Hugh Baker – a Rhodesian he finds himself fortunately in a wooden railways wagon – not metal like most of his companions from the camp. After a stop at Verona the two were numbers 3 & 4 to jump from the hole they had made. They soon swim the Adige River and then inspect their injuries. HB had a badly twisted knee and ankle. They slept in a vineyard and next day sunbathed and dried out. HB spoke some Italian and went to a house and taken in until 6 Yugoslavs burst in and carried HB off to their noisy X ‘Hide’ out in a village hall. Yugoslavs move on and Italians with a handcart come to take HB to house of town official Enilio. Wounds are dressed and bed given – until Germans commandeer the house and they hide in cage with food brought them. Early in October, HB’s legs recovered they leave intending to go to Como via Lake Garda. At Como they have an address. They keep to tracks but at Arco decide they must cross the town bridge but German sentry takes no notice of them. As HB spoke Africans they pretend to be Dutch sailors but are not believed. After ARCO they find 1st WW [World War] trenches. They climb 2000 ft and then down across valleys. A boy of 13 leads them for a bit. Come to valley leading to BOLZANO – busy with Germans traffic and river Oglio and see Capo di Ponte ahead. Skirt several villages. Look down on Edolo with Germans visible. Informed that the Swiss border is on Mount Combolo. On 12th October they set off at 4am, to climb. One would hide and watch as the other went forward. At 2 pm, HB grabbed his arm – had they been seen? To their right was a concrete block and on it SVIZZERA, In childish glee they took a few steps back and jumped over an imaginary line. They found similar blocks. Making sure they did not walk back in Italy they slowly descended when a soldier suddenly appeared – he was Swiss.

[Digital Page 3]

‘Where I have tunnelled’ might be the title of John Muir’s brief summary of his many attempts and final successful escape. In the Desert as early as April 1940 with the 7th Armoured when Wavel swept the Italians out of Egypt was wounded in an afternoon on Rommel’s backlash a year later and the same evening was captured. From Tarhuna to Naples and then Razzanello, Sulmona, Padula and then the strongest PW Camp of all Gavi for Muir was a persistent tunneller being captured at the face of one at Sulmona. At the Armistice he was fortunate to be in a wooden railways wagon taking the POW’s to Germany from which he and Hugh Baker of the RAF [Royal Air Force] jumped together and then soon swam the Adige river but HB’s ankle was badly twisted so he, speaking a little Italian crept to a house to explain their position. Immediately taken in and treated a Yugoslavs sent for who carried him off on their shoulders to the village hall. The noisy Yugoslavs fortunately leave and Italians arrive to take HB away on a handcart. Then to a donkey and a cave. When HB’s ankle is better they decide to try for Switzerland near Tirano. They pass 1st W.W. [World War] trenches. Though pretending to be Dutch sailors they are immediately recognised for what they are. Many villages are occupied by Germans but at Arco they just walk past the German sentry. One 13 year old son is sent to guide them part of the way. They walk through several villages and at one point a German staff car passes them. They look down on Edolo (after Capo di Ponte) and on the road are overtaken by a German staff car. The border runs alongside of Monte Combolo. They climb 300 metres.

[Digital Page 4]

[Title]JOHN MUIR

I volunteered to join the Army on Monday 4th September 1939 and after training I received my Commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Durham Light Infantry at the end of April 1940. I joined the Battalion in the Mersa Matruh Fortress in Egypt in August 1940 as a Platoon Commander in C Company. I was detached from the Battalion and attached to the 7th Armoured Division throughout Wavell’s massive victory over the Italian Army during December 1940 to March 1941. I rejoined the Battalion at Qassassin near Suez. The Battalion was in 2 Brigade with 3rd Coldstream Guards and 2nd Scots Guards preparing for an amphibious landing on an island in the Dodecanese.

In mid April the Brigade was rushed up to the frontier between Egypt and Libya to stem Rommel’s advance. After various engagements around the frontier the Brigade launched an operation named “Brevity” (and brief it was – a dawn attack and a dusk withdrawal). C Company with D Company in reserve captured, with considerable losses, the objective of Fort Capuzzo. I was wounded during the afternoon and when the Germans’ counter-attacked early in the evening I was captured by a German Panzer Light Infantry Unit. After treatment at a German Field Hospital I was taken by Italians to an Italian Military Hospital in

[Digital Page 5]

Benghazi. After 6 or 7 days I joined another Officer from my Battalion, Neil Ritchie, a Rhodesian, Hugh Baker, serving in the RAF [Royal Air Force] and an Australian Infantry Officer, Trevor Neuendorf. We were moved by stages to a P.O.W Camp at Tarhuna lying to the South of Tripoli. After 2 or 3 weeks we were on the move again, first by ship over the Mediterranean, then by train from Naples to PG 17 Rezzanello near Piacensa. However, on arrival there we were told that there were 6 Officers too many for the number of beds available. The Commandant wanted rid of two of the originals who had given trouble – Dougie Clark and Johnnie Birkbeck – so 4 volunteers were required. I thought that being outside of a camp gave the best chance of escape so I was one of the 6 who set off by train for Sulmona – no escape opportunity arose. At Sulmona I was in the first hut in the lower compound.

Towards the end of 1941 some of us in the hut were given permission by the Escape Committee to start a tunnel from the toilet area. After cutting through the concrete floor we dug a shaft 20 feet deep and tunnelled about 35 yards out from the hut and under the road running outside of the camp. We had about 10 yards to go to reach a suitable place at which we could ascend when one afternoon the Italians rushed in, went straight to the toilet area and there lifted the trap door leading to the shaft. I was working at the face at the time but was allowed to crawl out

[Digital Page 6]

before being taken to the Commandant and put in a cell for the night. This was about April 1942.

In May 1942 I and other P.O.W.’s were transferred to a camp in the Monastery at Padula. There I soon found a potential escape route but was refused permission by the Escaping Officer, possibly because someone else had applied. This may have been an attempt by Jack Pringle and Alastair Cram as described in Jack’s book ‘Last Stop Colditz’. I went over the roof while they went through a doorway into the same courtyard. A month later I was told that I was being sent to PG5, a punishment camp for “Pericolosi” at Gavi near Alessandria NW of Genoa. This was the Italian “Colditz” whose inmates had made at least one previous escape attempt since capture. There I rejoined Hugh Baker and Trevor Neuendorf and shared a cell with them, another Rhodesian, 2 New Zealanders and an Englishman.

Early in the winter our cell worked out a scheme to take us to a part of the fortress that could not be reached or indeed seen from the P.O.W.’s part. We took our scheme to Brigadier Clifton. It was a case of ‘Yes’ but not now so we knew that there was another scheme under way. This was a complex and arduous escape undertaken by South Africans assisted by David Stirling the founder of the S.A.S. [Special Air Service] and others including Jack Pringle

[Digital Page 7]

and Alastair Cram as described in Jack’s book. There is a very good report of this and a description of the fortress in the Times newspaper of 14th December 1945. The actual break out was on the night of 24/25th April 1943 with no successful escape.

After a period to allow things to settle we were given permission to start our scheme at the end of June. The scheme involved the lifting of the metal platform in one of the squat-down toilets, digging into the unused dungeons which we knew lay below the row of cells and seeing where we could go. It took about a month to remove the platform (using razor blades to separate the metal from the concrete with a minimum sign of tampering) and dig down alongside the sewage pipe through the roof into the dungeon. We were disappointed to find that the walls at the back and far end of the dungeon were the solid rock on which the fortress was built. The other side wall had a bricked up doorway from which we removed enough bricks to get into a passageway leading to another bricked up doorway. We bored a hole through this doorway, which we found opened onto a walkway, which was in constant use by the Italians. This left us with the front wall of the dungeon. We removed 3 heavy stones and started to tunnel under the courtyard of our cell compound towards the outer wall of the fortress. We had gone only 7 or 8 feet by 8th September 1943 when an Armistice between the Allies and the Italians

[Digital Page 8]

was announced by the Camp Commandant. Both he and Brigadier Clifton made it clear that we were to remain in the fortress until arrangements were made for our handing over to the Allies. However, the next morning we were wakened by gunfire as the Italian ration party was ambushed – most were killed with only a few escaping back to the fortress closely followed by a German S.S. [Schutzstaffel] Unit which took over. Three days later we were told to pack and be ready to move next morning. Our cell plus the Brigadier, David Stirling and others who had been involved in the earlier escape complete with our escape kits went into the dungeon we had found We heard the roll call next morning and the marching out of the prisoners.

We could hear the Germans rushing about with a great deal of shouting, hammering and bashing well into the evening and starting up early the next morning continuing into the evening. On the third day about 3 p.m. the hammering and bashing was at our “back door” – the bricked up one at the end of the passage leading into the Italian area. We heard German voices in the passage but then they went away but returned an hour later and knocked down the door into the dungeon. The German Captain was delighted that he had found all the missing prisoners – 58 in all – indeed had found an extra one because 2 prisoners who had been in hospital had returned on the 8th but were not re-entered on the Italian lists. Either the

[Digital Page 9]

Germans miscounted or a prisoner was still hiding. The Captain told the Brigadier that he had found the plan of the fortress and this had helped him find the hiding places including our dungeon – they never found our entrance but I don’t suppose they bothered to look for it. We were locked up that night but next day allowed to gather some kit from our cells. We had taken off our boots while in the dungeon. Some were brought up by the Germans but not mine, I found another pair – not my size – with which I had to make do and which gave me much pain on the walk later described.

The next day we were marched out of what had been our home for 15 months, loaded into buses and driven away with a massive escort of German Military Police in trucks and on motorcycles with sidecars. We stopped at Mantua where we were bedded down on the football pitch with guards all round the terracing. Next afternoon we were taken to a railway siding and loaded into rail trucks. Hugh and I were separated from our cell mates which as I learned after the war was just as well as they were in a steel truck whereas we were in a wooden one. The train did not move until dusk and as soon as it started we started cutting a hole in the front of the truck – front being the direction in which we were travelling. We had just finished making a hole big enough to squeeze through when the train stopped at Verona. We had an agonising half

[Digital Page 10]

hour holding a blanket over the hole while the German Guards walked up and down outside the train. We had drawn lots in pairs and Hugh and I were 3 and 4. After the train left Verona 1 and 2 climbed through and jumped. Hugh climbed through the hole and I followed to find that he had gone forward onto the buffers of the next truck – a mistake as it meant that his jump was at best sideways if not a little backwards whereas my jump from the buffers of the truck from which we had come was sideways and forward. There had been shooting outside of the train thought to be guards discouraging jumping off so Hugh and I arranged to lie still until the train passed. How glad I was to see the red lights on the last carriage disappear. I went back to find Hugh and we went down from the railway embankment through some scrub to find a river in front of us. Before we could do anything there was a rattling in the scrub and out burst an Italian soldier who took one look at us and turned and rushed back into the scrub. We decided immediately to go in the opposite direction across the river. In the moonlight it looked very placid but after wading a few steps we were carried away and swimming hard to keep afloat and make progress. We made the other side but at least a half mile down stream. We later learned that this was the Adige River flowing from the Dolomites down the Trento Valley. It was only when we came out of the water that we recognised the extent of our injuries from the jump. The palms of my hands were badly scraped, my knees were

[Digital Page 11]

scraped but the skin not broken and I had a very sore chest, which must have taken much of the impact on landing as my pullover was ripped down the front. Hugh was in worse condition with hands and knees scraped but with a twisted knee on one leg and a twisted ankle on the other. We were soaking wet and cold. We set off up a slope away from the river with me helping Hugh who was walking with great difficulty and in great pain. Soon we came to a vineyard and at the top there was a patch of scrub – bushes about 6 feet in height with branches reaching almost to the ground. We crawled in, huddled together and fell asleep. Next morning we found that the scrub was quite extensive so we crawled in deeper, took off our clothes and found breaks where the sun came through to dry them and heat ourselves. I went into the vineyard and picked bunches of grapes which we ate along with some chocolate which we had. We took turns to sleep and then dressed to move at dusk only to find that Hugh’s knee and ankle were very swollen – the ankle so much that he couldn’t put his boot on that foot. We discussed the dilemma and decided that Hugh, who spoke fair Italian, would go to an isolated house nearby to seek help. I would take him down but hide outside so that I could go on my way if no help was available. After 10 minutes of anxiety Hugh came to the door and called me into the house. He told me that the daughter of the house knew some other escapees, Yugoslavs and had gone to fetch them. Meantime the woman was bathing Hugh’s hands and

[Digital Page 12]

knees, applying an ointment and wrapping them in cloths. She did the same for me and then made us coffee. Suddenly there was a great commotion and 6 or 7 burly and noisy Slavs burst into the room – there was a great deal of handshaking – and two of them picked up Hugh and took him out of the house and I was hustled out. The two who had taken Hugh out placed him on the shoulders of a big fellow who set off down the road followed by about 20 others all shouting and singing. We rushed into a small village and into a sort of village hall where they were staying. They wanted to go on partying and one, who spoke a little English, to go on talking but by now it was 2 a.m. and Hugh and I were exhausted especially Hugh as the manhandling he had received worsened his original injuries. We fell asleep and it was midday before we woke.

During the afternoon there was a lot of talk between Hugh, 2 Italians, the Slav who spoke English and a Slav who spoke Italian. Hugh reported that the Slavs intended to move away and that the Italians had arranged to take care of us. At dusk 4 Italians arrived with a handcart into which they loaded Hugh and off we went into Avio where we were settled into a bedroom in the house of Emilio (I don’t know his surname but think that he was an official of the town administration). Our wounds were dressed again with the same ointment, which was most soothing and effective. It

[Digital Page 13]

was great to be in a proper bed for the first time since my leave period in Alexandria in March 1941.

Next day an unpleasant surprise was the arrival of the advance party of a German unit requisitioning accommodation including the bedroom we were in. This led to feverish activity by our host and other Italians resulting in our being moved out in the early hours of the morning with Hugh mounted on a donkey. We were taken into the hills to the east of the town to a cave which had been set up with a flooring of branches and shrubs covered with tarpaulin, sheets and blankets. We lived in the cave until 28th September with food brought up regularly by somebody – on 26th September we had a party for Hugh’s birthday with Emilio, Maria, Lino and Aurelio. By now Hugh’s knee and ankle were much less swollen and he could walk a short distance but still could not get his boot on. During 28th September the German unit moved out. Late in the evening we were brought down from our cave to Lino’s house where we stayed until 2nd October when we moved to Aurelio’s house. Hugh was now able to wear his boot and we were taking a walk after dark each night. We had been ‘kitted out’ with Italian clothing and received a 1932 road map so we were keen to get on our way. We left letters with all our Italian friends addressed to the British Authorities advising of the great help we had received.

[Digital Page 14]

So at 5.30 am, on 5th October we were given a fond farewell and newly baked bread and cheese and we were on our way. Our intention was to get to Lake Garda, steal a boat in which to cross the lake, take to the hills and head for Como to an address where we knew we would get help. We started on the road northwards from Avio but towards 9 it was busy so we took a track heading north and into the hills. This was hard on Hugh’s knee and ankle but it was a lovely sunny day so we had many stops. Towards dusk and fairly high up we came upon an isolated farm, which seemed a suitable place to stop for the night. Hugh having been educated in South Africa spoke Afrikaans so we decided to say that we were Dutch seamen who had left a ship at Venice and wanted to get home. Hugh spoke to me in Afrikaans and I replied with one or two words in Afrikaans, which Hugh taught me, but mostly in grunts or shakes or nods of the head. We went to the door and Hugh told his story to an elderly woman who had answered his knock. She was joined by her husband and Hugh told the story again. I don’t know if it was believed or not but we were invited in. We were given a meal of ‘polenta’ and bread and cheese then shown into a barn with a hayloft where we spent 2 hours on watch and 2 hours asleep until 6 a.m. We were given a cup of coffee and more bread and off we went on a track heading north running at a good height along the west side of a valley.

[Digital Page 15]

About midday the track started to go down towards a road leading into a town so we knew that we had come too far north. We went back up the track and found another one heading west – I don’t know how we missed it before. We took this track, which climbed steeply then levelled off. Soon we came to a ridge of rock and the track headed North running parallel with the ridge which stopped after a short distance giving us a view of Lake Garda which looked lovely in the sunshine. However we were looking down on Torbole which was not a lovely sight as it was full of Germans – it seemed to be an H.Q. [Head Quarters] of some sort but we didn’t wait to see. We retreated the way we had come back to the original track down to the road we had seen, through the town which was Nago and on a track running beside a river which was flowing towards Lake Garda looking for a bridge to cross this river. We were approaching another town when the track rejoined the road and we could see that this road crossed a bridge and entered the town (Arco). As there were a lot of people crossing the bridge we decided to do so but having set out along the road we saw that there was a German sentry at the far end. He wasn’t checking papers nor seemed to be interested in passers by. It might have been more conspicuous than carrying on if we had turned round and gone back up the road so with at least my heart in my mouth we moved onto and over the bridge – I had difficulty in keeping an even

[Digital Page 16]

pace and after passing the sentry, not breaking into a run. More problems faced us as it turned out that Arco was a hospital town – red crosses all around and many wounded soldiers – and then my worries were added to by Hugh’s decision to buy a newspaper in a shop full of German wounded – according to Hugh he wanted to see how the war was getting on. Arco proved to be a large town and by dusk we were still not clear of houses and there were very few people around so we urgently required shelter. We thought we might need to go to ground in a garden but then we came to a monastery so sought and were given asylum for one night only. We were given bread and water and a bed that was rock hard. We left the next morning as soon as there were people about. Having decided that Como was out of the question we decided that we would try for Switzerland at its nearest point (near Tirano) especially as the area ahead did not seem to be heavily populated – little did we realise this was because it was so mountainous as we soon found out and worse still we found that all the valleys were at right angles to our route.

That day 7th October, we started climbing very soon after leaving Arco following a very bad path and taking it very slowly. When we reached the top there was a flat area with 1st World War trenches facing north – presumably Italian who were on our side then. We didn’t see any Austrian trenches so those we saw were either in reserve or for training

[Digital Page 17]

or as a memorial. They were very complete with firing steps, revetments and dugouts. It was late afternoon when we got down into the next valley where we sought out an isolated farm, told our tale, given a meal of potatoes baked beside the fire, with cheese and a bed in the hayloft. We were so exhausted that there was no question of one on watch while the other slept – we both slept and were only wakened when the farmer went off to work about 7 am. We set off without breakfast – none offered – climbed about 2000 feet over a saddle and down to a valley where we walked along a road, crossed a river by a bridge which was unguarded, climbed again to a saddle, then down again to a village (Brione) which we reached in early afternoon greeted by a tremendous lightening display with thunder and torrential rain. The rain was so heavy we had to get shelter as soon as possible so we went to a house set apart from others and asked for shelter telling our tale to the lady who opened the door. She was joined by her husband who invited us in. He gave us towels and some clothing and took away our soaked clothes to dry them. We were given a good meal with wine. During the evening it became clear that our Dutch sailor story was not believed and that they knew we were escaped POW’s. We had to agree and were told that they would help us on our way. They gave us some extra clothing and a more up to date map on a greater scale. I regret that I cannot remember their surname. We slept in their living room and the next day they sent their son Silvio

[Digital Page 18]

(aged about 13) to guide us on our next stage. He was a lovely boy and we were sorry when he left us about midday.

During this day we had 2 climbs and 2 drop downs into valleys and finally a further climb through a forest where again the rain started. We came across a woodcutter’s hut with a charcoal fire, which we huddled over to dry our clothes. The woodcutter was not best pleased to find us there but gave us a cup of coffee and some cheese.

Next day after a further short climb through the forest it down again into a valley through which, if we were correct with our navigation, the road to Bolzano and the River Oglio should be running. We walked on the road for a short distance but didn’t feel safe as there was a lot of traffic including German trucks etc. and we could see a town ahead of us. This was Capo di Ponte proving our navigation to be okay. We climbed up the side of the valley and found a track, which was running in the same direction as the road. This track took us to a number of small villages which we skirted either up round and down or down round and up – Hugh preferred one and I the other but I can’t remember who preferred which – I think it was to do with the state of our feet but really it was the same whichever way we went – after 3 or 4 ‘skirtings’ we gave

[Digital Page 19]

up and walked through the next few. Yet again we told the tale at an isolated farm and were given a meal and a blanket in a barn.

The next day, 11th October, we continued along the side of the valley still running parallel to the road and soon we were looking down on a sizeable town (Edolo) with a lot of Germans to be seen. We were too far to the east so we headed west over another road. It was here that we had our worst scare. We were walking along this road looking for a track when we were overtaken by a German staff car and 30 yards or so past us the driver revved up his engine and changed gear. We thought that he was stopping for us but it turned out that he was preparing to cross a bridge and take the bend beyond. We got off the road and started climbing into the hills where we felt safe. As usual we soon were on our way down into a valley and again were given a meal and shelter at a farm. Hugh asked the farmer and his son if they would guide us over the border into Switzerland but they refused. However, they told us that the border ran along the side of Mount Combolo with part of the mountain in Italy and part in Switzerland and that as far as they knew there were no fortifications at that part of the border. Hugh and I decided to start early the next day, get onto the mountain which, according to our map, was about 3000 metres climb up to find a hiding place and hole out until dark.

[Digital Page 20]

When we would climb slowly to the top of the mountain and know that we must be in Switzerland.

On 12th October we set off at 4 am walked along the road past Tirano and on to Villo di Tiarno at the foot of the mountain arriving about 8 am. We found a track leading upwards into a forest We didn’t go together – one of us (a) hid and kept watch while the other (b) went 50 or 60 yards and lay down (a) joined (b) and went on another 50 or 60 yards and so on each counting the number of paces he had taken – all this elaborate procedure proved unnecessary as soon we were in a thick mist. We decided to go on up rather than wait for night. We still moved as quietly as possible. About 2 pm Hugh grabbed my arm – I immediately thought we had been spotted but ’no’. He pulled me back and over to his right and pointed to a concrete block showing on the side we were on the word “Svizzera” and on the other side “Italia”. We searched to the left and right and found similar blocks. We started to walk into Switzerland but with one accord and without a word to one another we turned walked back into Italy joined hands and jumped over an imaginary line between two of the blocks. Childish and foolhardy but an expression of our joy at being free after nearly 30 months of captivity. We went on into Switzerland watching carefully in case we crossed again into Italy. We were not sure if it was safe to start going down rather than up. After a

[Digital Page 21]

while we sat down and rested for an hour. We thought that during the last half hour of walking the track we were on was more level and indeed tending downwards. While we had been resting the mist had risen and the sun was shining. We set off again still keeping a lookout and being as quiet as possible. I think that it was about 4 pm when we got another shock. A soldier stepped out of a perfect hide with a rifle pointed at us and a voice behind us said ‘‘halt” this from another soldier likewise with rifle pointed at us. Their uniforms and helmets were different from German or Italian so we were happy to put our hands up. Hugh said in Italian that we were prisoners who had escaped. The soldier in front spoke some English so we told him who we were. We were escorted down to Barracks where we were greeted by the cook “ah two English boys, have some tea yes?” The answer was “yes” and we didn’t advise him that we were a Rhodesian and a Scot.

The next day we were taken to Campocologno then by train over the Bernina Pass to Samedan where we were handed over to British soldiers operating in “civvies”. We were put up in a hotel, were interrogated and watched by I think both the British and Swiss. After 4 days we were told that we had been authenticated. The next day we had a trip to St Moritz and the next again we were on our way to Wil, which was the HQ [Head Quarters] for the hundreds of prisoners who had escaped into Switzerland. The next

[Digital Page 22]

day with very little notice Hugh and I were split up – he going to join the RAF [Royal Air Force] Officers in Arosa and I going to a small village Schomengrund in Canton Appenzell where about 100 British troops were billeted. It sad to be separated. When we arrived at Wil we had to sign a declaration to the effect that we would not attempt to leave Switzerland without permission of both British and Swiss Authorities.

I don’t know what happened to Nos 1 and 2 who jumped before Hugh and I nor if any of the other 20 from our truck got away – none arrived in Switzerland. While in Avio] we heard that on the night we jumped someone had been killed when jumping from a train about 20 miles further up the line but could not get any more detail. It was rumoured that he had hit a signal.

Rex Woods in his book “Night Train to Innsbruck” describes jumping off a train and he crossed into Switzerland on Mount Combolo.

[Digital Page 23]

[Handwritten notes by from Keith Killby]

John Muir, DLI [Durham Light Infantry] Mersa Matruh April 1990. 7th Armoured in [2 words unclear]

April 1941 rushed forward to stem Rommel’s advance. Wounded near [1 word unclear] Capuzzo in afternoon. Captured in Evenin, via Tarhuna. Boat to Naples ?Rizzanello (near Picenza) then Sulmona.

Just before tunnel was finished he was discovered by Italians when J.M no [1 word unclear]. PADULA. The Gavi (report on Gavi in ‘The Times’ 14th December 1945). Again starts to tunnel. Germans take over. Hut in [1 word unclear] which Germans finally discover. After 15 months in Gavi marched out. J.M [John Muir] [1 word unclear] to be in wooden trucks. Train stops near Verona. Hugh Baker (RAF) and J.M [John Muir] jump. Swam the Adige. Both damaged by jump but Hugh Baker twisted ankle and unable to proceed walking so call at house and [1 word unclear] for 6 Yugoslavs who take them to Village Hall. Yugoslavs leave and Italians arrive with hand cart and both keep in bed. Germans arrive. Hugh moved on a donkey. Go to cave. With Hugh’s ankle both decide walk and climb into the mountains but [they] find many villages are German occupied but at ?Arco just well [1 word unclear] German sentry. Aim for [1 word unclear] Switzerland near TIRANO. Pass 1st World War trenches (their story of being Dutch sailors not believed as Italians suspect they are PoWs.

13 year old son sent to guide them. Find wood [2 words unclear] Capo di Ponte. Walk through deserted villages. Look down over Edolo. Overtaken by German staff car. ?Barda ran along side of Mount Combolo. Climb 3000 metres.

[Digital Page 24]

[Handwritten letter from John Muir to Keith Killby dated 28th February 1998]

Dear Mr Killby,

I am horrified and ashamed to see that I am only now replying to your letter dated 13th February 1998. It has been on my mind for quite some time. It is said that “the road to hell is paved with good intentions” and that procrastination is the thief of time (or something along these lines) and I regret to [word unclear] that I owe a good [word unclear] and thief. I have a slight excuse in that I have been involved in the amalgamation of the legal practice which I carried on with my son with another Glasgow firm and my retiral from the new firm after settling one into the other and my retiral from the practice of law. I had commenced my law degree in 1937, qualified in 1946 and joined my Uncle’s firm in 1947. I retired on 31st October 1997 but have been busy over the winter finishing off items of work with which I was involved and completing the accounts of the business not made easier by changing of rules of taxation and introduction of Self Assessment. In addition I’m getting older- now in my 80th year.

[Digital Page 25]

As far as I know few escaped from the P.G. 5 inmates. PG 5 was at Gavi in Liguria about 40 miles north of Genoa. It was in an old fortress set up in June 1942 for escapees or attempted escapees. There was a very good article about it in The Times of 14th December 1945 (page 7 I suppose that it was the Italian equivalent to Colditz but it did not figure in a film. It was like the Colditz in appearance.

At 6am on 9th September 1943 we awakened to shooting as a German detachment shot up an Italian ration party and took over the camp. On the 13th at very short notice moved out the camp but discovered that over 50 Officers were missing. Six Officers in my room (or cell to be more exact) had been working on an escape attempt in the course of which entry had been gained to unused chambers in the foundations of the fortress. Unfortunately there was no exit from these chambers except by a dug tunnel which we were working on. Our six plus the senior Officers including David Stirling in all 20 went underground in our chambers while others hid in all sorts of places – in wood piles, in piles of earth, under stairs, in roofs etc. The Germans in their usual methodical way didn’t look for entries but knocked

[Digital Page 26]

down walls and turned over everything which could be a hiding place – so I and all others were found.

On 16th September we were moved by bus to Piacenza and then to Mantua where we were entrained on 18th. There were 24 of us in the truck and most of us had hacksaws so we were able to cut a hole in the front wall of the truck onto the buffers. We drew lots – Hugh and I were 3 and 4. After a stop at Verona Hugh and I jumped at midnight probably in the region of Ala and beside the Adige river. We swam over the river and after walking some distance we holed up in some undergrowth beside a vineyard. Hugh had had a very bad landing from the train and next day could only hobble. We stayed where we were until dusk and in the evening we approached an isolated house and through the daughter came in contact with people in the village of Avio lying close to the west bank of the Adige and almost due east from Malcessine on Lake Garda. If you wish for your records more details of our stay in the village and in a cave in the hills above the village until Hugh was able to walk I can let you have them. We left for Switzerland on 5th October and after hard walking in the mountains we crossed into Switzerland north of Tirano on 12th October.

[Digital Page 27]

I also have more details of our journey and crossing.

When we reached Switzerland I made notes of those who had helped us and gave them to an Embassy official. I had a copy but unfortunately I cannot find them. I remember the first names Emilo and Maria in whose house we stayed also Aurelio and Lino (I think Lino Tapparelli) and their wives.

I am pleased to say that I now have re-found Hugh – he is now 84 and while healthy is not so alert. He has returned to Zimbabwe and is living in a Retirement Home near his 3 sons who are all farmers.

My own Army history is that I was commissioned into the Durham Light Infantry in the Spring of 1940 and joined the 1st Battalion in Mersa Matruh in the summer. From December I was a Platoon Commander in a Detachment attached to the 7th Armoured Brigade through Wavell’s campaign. At first with dummy tanks and known as 10th R.T.R. [Royal Tank Regiment] (I doubt if they fooled the enemy) and later as the coastal flank for the capture of Sidi Barani and further along the coast towards Bardia with the capture of thousands of Italian troops. After the capture of Tobruk (during the siege we were used

[Digital Page 28]

for patrols) the detachment was used for patrols rounding up pockets of Italians in the coastal villages towards Benghazi.

The detachments rejoined the Battalion in the Canal Zone and brigaded with the 3rd Coldstream Guards and 2nd Scots Guards to form 22nd Guards Brigade. Light Infantry marching with guards was an unusual sight but not something in which to be involved especially as a long legged Light Infantry man. The Brigade was training for an amphibious landing in Rhodes (I think) but with the arrival of the Germans was sent to the frontier at and around Sollum and Halfaya Pass. After various skirmishes in April and May a Brigade attack was launched with the D.L.I. [Durham Light Infantry] responsible for the capture of Fort Capuzzo and the airfield beyond. The attack was successful but so costly in men that the German counter attack could not be resisted.

When I came out of hospital I went through various transit camps ending at Tarhuna which I think had as S.B.O. [Senior British Officer] the Col. Hugo de Burgh mentioned in your 7th Annual Report. Shipped to Italy I was at Resanella near Piacenza for a few days before being sent to Sulmona. I was

[Digital Page 29]

was at the face of a tunnel when it was discovered by the Italians. Much of the earth from this tunnel was put by Duggie Clarke and me in the ceiling / roof space of the hut and I believe that the ceiling which was of very flimsy construction collapsed after I was transferred first to Padula and 3 months later to Gavi.

This has been a very long letter but in your 7th Annual Report you asked for stories of escapes. I am sorry that I did not know of the Trust earlier. I should like to grant a Deed of Covenant now so please let me have the necessary form as soon as possible. Please also let me have a copy of your 8th Annual Report when available. I have not yet contacted John Pennycook but I shall do so later this month when I get clear of all connections with business.

My clipping from the Times is very frail but I enclose a photocopy which I hope you will be able to read.

With very best wishes to you and the work of the Trust.

Yours sincerely

John Muir

P.S I think that 2 others from Avio were Giovanni and Pietro.

[Digital Page 30]

[Handwritten letter from John Muir to Keith Killby dated 3rd October 2001]

Dear Mr Killby,

Thank you for your letter of 26th May – sorry to be so long in replying but it is only now that I’ve written out the story of the escape of Hugh Baker and me from my notes which I recently found – in true Army tradition Hugh was known as Dougie and I serving in an English Regiment, was known as Jock.

I enclose a copy of the escape for your archives. The writing of it brought back vivid memories – not exactly painful but provoking thoughts of the war years which were painful.

I can assure you that there

[Digital Page 31]

there was no need for acknowledgement of my annual contributions. I was pleased to contribute and only regret that I did not know of the Trust at an earlier date. I appreciate the tremendous amount of work you have given to the affairs of the Trust.

I was interested to know about the “Trail” – would have liked to be there but my movements are restricted as my wife is a stroke victim and has been confined to a wheelchair for 16 years.

With kindest regards and best wishes.

Yours sincerely

John Muir

[Digital Page 32]

[Handwritten letter from John Muir to Keith Killby date unknown]

Dear Mr Killby,

I am writing to you in your now official capacity. Let me say straight away how much I acknowledge and appreciate your immense work in the founding of the Trust and it’s administration from foundation until your standing down as Honorary Secretary.

It is my regret that it was not until the mid-1990s that I became aware of the Trust and its good work and also came in contact with your good self.

My wife, after over 16 years of grave incapacity confining her to a wheelchair died last June. I now have more time to read through your Annual Reports from March 1996 to March 2002 bringing memories and thoughts of my experiences of the war before, during and after my capture – confinement in various hovels along North Africa to my first camp at Tarhuna (with I think Col. De Burgh as S.B.O [Senior British Officer] then voyage to Naples and camps Rezzanello, Sulmona

[Digital Page 33]

Sulmona, Padula and PG5 at Gavi. I always remembered my escape to Switzerland but even more so due to your more or less insistence that I prepare a detailed narrative for the Trust’s records.

In the 2002 report you report the death of Douglas Clarke. When I was in Sulmona I was in an escape team with a Douglas Clarke – he and I were responsible for disposal of soil from our tunnel into the roof space of our hut. Because we were the lightest in weight in the escape team. I met up with him in Switzerland – I think he had escaped from Fontanello – and again after the war in the UK, but lost touch. He was last heard of lived in Storrington.

With Kindest Regards,

Yours sincerely

John Muir