Summary of Norman Kingham

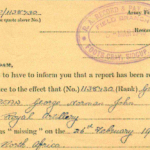

Norman Kingham was captured around Apr 1941 when his unit was retreating from the general German advance while he was trying to salvage supplies from an overturned truck. During the retreat he was able to bury some £2million pounds and documents in the desert which was eventually recovered. He spent 2 years at Camp PG 78 near Sulmona in Italy. Being a draughtsman Norman was extremely useful in helping to forge passes and documents for fellow prisoners. He eventually escaped during confusion at camp when German forces arrive to replace the Italian guards. Had one very narrow escape from recapture by escaping into a sewer and another when he ends up in no-man’s land and survives an artillery bombardment. He did however make it back to the Allied lines.

Norman was presented with a Military Medal for his prison escape but he refused it because of his disgust of Army policy that only commissioned officers could recommend other solders for bravery medals. He ended the war back in Middle East where because of his architectural background involved him in various construction projects.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital Page 1]

Notes on Manuscript of NORMAN KINGHAM

(Draughtsman and architect who pursued, some of his profession in army service, POW camp and while being pursued.)

In the desert in the early days with 2nd Army Div. (?) Being a draughtsman and so to maps brought him in contact with many Generals, Eden and the like.

Good story of Padre who had taken a service for ‘some Free French in grey uniforms’.

NK is raiding an overturned truck in the desert one night but recognises fellow raiders as German. Buried some £2 million pounds and documents in desert – later from P.Camp sent home compass bearing for their recovery. Generals Neame, Gzmbier Parry and O’Connor being interrogated at same time. But later claims that O’Conner who had taken off tabs was ill so disclosed his identity.

When recruited to unload bombs in Tripoli harbour NK and others managed to ensure that most rolled into the sea and nearly shot. Later, as a sapper, had to help defuse a bomb with German sapper officer.

At Sulmona there were compounds for Sen. [Senior] Brit Officers, Officers, Sergeants, O.R. [Other Ranks], Greeks, Free French and Yugoslavs. The one who cut the bread took the smallest slice.

Handcuffed after Dieppe raid but, with false keys they made such a farce of it that the Italians gave up. Good description of Salle when they escaped and the dangers for them and Italians, including just surviving the sudden escape into a sewer, into which the Germans dropped a grenade. Found two Germans, one just alive, who had their throats cut by Free French.

Snow and cold made life almost impossible, sleeping in snow holes, being pursued by skiing Germans. End up in the area of Guardigrele when the battle nears. They and a German gun position seem to share the same haystacks but when a shell demolishes theirs they survive. They press on towards the Allies. Exhausted two women go out to find ‘the Americans’. New Zealanders appear and they are through.

NK and his fellow draughtsman make many unorthodox army moves including refusing MM’s [Military Medal] and sent to the glasshouse etc. In ME [Middle East] again and ends up in the troubled Palestine with Italian POWs and a young Arab in retinue.

It would seem that NK wrote his story some years afterwards and without notes.

Some of his timing of events are a bit amiss and one wonders whether some of his memories are exact – but of course often accurate accounts seem incredible.

[Digital Page 2]

Manuscript of NORMAN KINGHAM

Introduction

1938 Joined TA [Territorial Army] 3rd Cheshire Field Squadron RE Sapper.

1939 Camp in Monmouth became driver. Got a stripe but lost it almost immediately.

Called up the day before the declaration of war — no accommodation so lived in the Grandstand at The Oval, an athletics ground in Wirral. Later in old houses in Spital. Demolition training Silverdale, Autumn in Hulme Hall.

1940 Unit moved to Doncaster. Lived in Rossington Hall. Bill Knight had task of lettering latrines etc. in our billet. A staff officer asked him to put his name on his personal kit. Bill’s lettering was superb. Lots of other officers from Divisional HQ [Headquarters] asked Bill to do their names on theirs too. Bill became overworked and sent for me to help at HQ [Headquarters] in 2nd Armed Division in the Bell Inn, Barnaby Moor. Whilst Bill went on leave I was left to do the lettering.

[Handwritten annotations by Norman Kingham on right hand side of page]

We were at the University together, joined the TA [Territorial Army], were captured and escaped together & eventually became my partner in the practice of Kingham Knight Associates.

[Main text resumes] I was told to put a sign on the General’s door (a bedroom in the Inn) “PRIVATE”. There was no table so I mixed colours on the floor. The general unexpectedly returned, very distressed (Major General Hopblack). He told me to get some maps of Yorkshire and paints to colour defence areas against invasion. He seemed very pleased. I was then instructed to get a clean uniform for the next day. Returned to my unit in Rossington Hall. Next morning the Quartermaster refused to give me a new uniform. Back in the Bell Inn the General was furious – sent me back in his staff car with instructions that his orders were to be obeyed. I got two new uniforms – one for Bill and one for myself. The general told me to move into cottage by the Inn (Pear Tree Cottage). Randolph Churchill was his liaison officer, but the General could not stand the sight of him.

One day the General went off to London for instructions, but did not return – we heard that he had been murdered outside the War Office.

Our new General arrived, a Major—General Tilly. He appointed Bill and I as members of his staff. His senior officers were:

G1. George Young-husband Colonel;

G2. Derek Schrieber, Major;

G3. Geoffrey Hardey Roberts, Major.

There were many problems facing Britain at that time:

i) Invasion threats

[Digital Page 3]

ii) No equipment!

iii) Forces being pushed out of Europe.

The Bell Inn had a small landing strip. One day the Duke of Gloucester arrived with Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands. He had flown to Holland and returned with her jewellery. For security it was put in our Pear Tree Cottage. There was a great fuss. CIGS [Chief of the Imperial Staff] arrived (Sir John Dill arid Ironside – Sir Anthony Eden.).

Randolph Churchill returned with a cine camera to record the visit, but Sir Anthony refused him permission. I learned that politicians ‘were and still are more important than executives.

The Divisional HQ [Headquarters] moved then to Thorsby Hall in Sherwood Forest. Bill and I were formally transferred from the old unit to the Divisional HQ [Headquarters] as Topographical Draftsmen.

The Division was prepared to go to Norway. The HQ [Headquarters] moved again, but this time to Guilsborough Hall, a small beautiful manor house in Northamptonshire. It had until the previous day been occupied by a German and his South African wife – a friend of Hitler’s, They got away by air; (see photographs in my album). Bill and I occupied the ground floor cloakroom, as our map room and sleeping quarters. One night at 2am, the G3 [General Staff Officer Grade 3] aroused us and asked for maps of Africa – “bring them to the Billiards Room”. We were in pyjamas. Those present in uniform were:

CIGS [Chief of the Imperial Staff] and staff

Foreign Secretary etc.

Generals, G1 [General Staff Officer Grade 1] and G2 [General Staff Officer Grade 2].

The maps were laid on the table and we were told to remain. Egypt apparently was leaning towards the axis and had to be persuaded to change their mind.

(The King of Egypt was being advised by his ministers that if he were to side with Germany, the British (who were there under a league of Nations mandate) would be kicked out and Egypt would once more be independent. Our commander in Cairo had placed his artillery facing the Abdin Palace in a show of force. King Farouk decided to side with the Allies).

Our General in command was sacked. (his old friend, Brigadier Tilly was now our Divisional Commander). Eden told us that our new division was not to go to Norway, but instead to Egypt. At 4am we all had tea. Eden had realised that the two lads in pyjamas were only Sappers – everyone else was either a field officer or Civil Servant. We both had to sign the official secrets act before leaving the billiards room.

Next day the General sent G1 [General Staff Officer Grade 1] and the “Heavenly twins” (Bill & I) to Towcester Racecourse to select maps for an Armoured Division. Bill and I stayed two or three days and brought back about six tons covering Egypt and North Africa. (The Towcester Racecourse stands were an emergency map centre of the Ordinance Survey whose HQ [Headquarters] was at Southampton).

We returned to Guilsborough just in time to pack for Maddingley Hall, Cambridge. The General had a slight fever – no wonder!

Bill and I took over the stables at Maddingley for our maps – the house became Div HQ [Division Headquarters]. For the next few weeks we had extra security.

Commanders of the various Brigades who would accompany us reported for briefing. Instructions were given, equipment and stores ordered, transport to the port of embarkation arranged but no destination was given at the time.

[Digital Page 4]

Bill and l had separate embarkation leave. The night before my leave we were bombed and I took home a kit bag full of ripe pears which had been blown off the trees in the orchard.

That evening the sentry at the lodge gate reported that an elderly private insisted on seeing the General. He was sent up to me in the stables.

Apparently he had been our Commanding Officer in Cairo who had placed the guns outside the Abdin Palace.

It was the then about 11.30pm. I awoke General Tilly described the soldier and was told to bring him over. Tilly had been one of his Brigadiers in Cairo – they were both delighted to meet. He had surrendered his commission but then rejoined as a Private. He stayed about a week.

G1 [General Staff Officer Grade 1] returned from leave with his wife and two young daughters. The girls were placed in my care – we went to the pictures, walks and they played in the map room over the stables.

The general returned from his leave in a very distressed state. His wife had died and his only daughter had gone to the USA with her husband. He looked poorly – parchment, coloured.

London was being bombed — we could see the flames, hear the bombers and the news of the war was bad.

One night he came over to the stables to get away from the staff officers. A messenger came across – I think it was his Secretary Norman Bailie, with further sad news – his mother had also died.

I went for Tristran, his Batman, and we put him to bed but stayed with him all night.

Two days later we were on the SS [Steam Ship] Strathallan in the Mersey. She was anchored off Seacombe and we watched the ferry boats passing to and fro. We were there for three days.

The General joined us with the pilot and we sailed out past the Fort and Lighthouse. It was October 1940 – we met our convoy in the Clyde.

Other ships in the convoy were:-

Strathnaver

Strathayrd

Empress of Canada

Duchess of Bedford

Reine del Pacifico

Andes

Britannic

etc:

We sailed West to US waters then South to the Gulf and East to Africa and called at Freetown for water.

Bill and I moved into the promenade deck of the General’s suite to establish our map room. There was an enormous amount of planning to do.

We allocated maps and worked with our new G2 [General Staff Officer Grade 2]. Major Schrieber our original G2[General Staff Officer Grade 2] left us at the Bell Inn to join the Duke of Gloucester as his ADC [Aide de Camp]. The Duke was a Major-General and had been appointed Governor General of Australia.

Our new G2 [General Staff Officer Grade 2] was a Major Lloyd (“Rosie” Lloyd).

[Digital Page 5]

We sailed South to Freetown for water then to the Antarctic, then East into the Indian Ocean to avoid U boat packs, then North to Durbane General left the ship in Durban (December 40) and went by air to Cairo. The convoy continued up the Red Sea, Suez Canal and finally to Port Said. We were driven to Moascar Camp where our work really commenced.

The Divisional HQ [Headquarters] was set up at Moascar, but by coincidence the 3rd Cheshire Field Squadron occupied the next camp about 100 yards away. Met Roy Eastwood, Doug Peel and the gang of TA [Territorial Army] friends. I spent a leave at Cairo – visited the Museum and helped pack exhibits into tea chest for evacuation during the war. These were then taken by army transport to Sakkara and placed in the enormous Tombs of the Sacred Bulls until after the war. I was fascinated by Tutankhamen’s slippers and spare clothes. He had rolls of spare cloth (it seemed in excellent condition) and most of the old furniture out of his tomb. Sadly some of the gold extremities were mixed up. Fingers, toes and penises etc. on the mummies were sheeted in gold. There was a tea chest half full of extremities, rings, ear rings etc.; I can’t imagine how they would sort them out!

In late November we moved South to the desert by the Pyramids. Bill and I had taught ourselves navigation and our new roles would be as navigators to the advanced and near Divisional Headquarters. Meanwhile Wavell’s 7th Armoured Division had cut the Italian lines of communication and most, of their army under Martial Gratazani and surrendered.

Thousands of prisoners were flooding East into Egypt.

Our Div [Divisional] HQ [Headquarters] stayed in the desert and our General went to Cairo for a further meeting with Sir Anthony Eden. The 7th Armed Division were withdrawn and returned to England. I joined the long range desert patrol for navigation experience and visited their base at Jairabub from where Colonel Combes had set off. Apparently German forces now threatened to take Yugoslavia, pass through Greece and Turkey to attack India.

All our spare armoured brigades were immediately directed to Greece together with 3rd Cheshire Field Squadron.

This left our Division without tanks, guns or sappers. We were given Indian Infantry Brigades, Field Hospitals and odds and sods.

At Moascar Doug Peel had contracted a bad dose of impetigo – when I last saw him he looked dreadful – scars and scabs all over his body. He went into hospital.

Turkey was neutral in the last war but by agreement the British Government were to send “civilians” to Turkey to construct airfields in case of emergency. We could then move in if necessary before Germany.

Doug made a good recovery in hospital but to his surprise he was not returned to the 3rd Cheshire Field Squadron, but was discharged in Suez and as a civilian joined this special force for Turkey.

He spent most of the war there – this is another interesting story!

General Tilly went up into Libya to our advanced forces – his car was hit in an air attack but although he was not injured he developed jaundice and died on the way back to Egypt. I never saw Tristran, his batman, again.

Our G1 [General Staff Officer Grade 1] (George Young-husband) was now in command. In journey 41 we moved up into the desert and on to Cyrenaica. Bill was with Advanced Div. [Division] HQ [Headquarters], I was with rear HQ [Headquarters]. Our new General joined us from England. Major General Gambier Parry – had been the King’s ADC [Aide de Camp] in London. It was winter and the weather was bitterly cold

[Digital Page 6]

at night but hot by day. One night I slept in an Italian dug out and became covered in lice!

The 2nd Armoured Division now had completely taken over from the 7th Armoured Division. Our only armour was old tanks and transport from the 7th Armoured Division which could not make the 1,200 miles back into Egypt. Five A13 tanks, some gun carriages and field guns.

The RAF [Royal Air Force] had about two Hurricanes, no bombers but we had an old Handley Page bi-plane attached to one of the two field hospitals.

Our basic equipment was hopeless. There was no proper water supply, 4 gal [Gallon] petrol cans were to be reused for drinking water. Even when boiled we risked lead poisoning.

German Hienkel bombers began to take an interest in us. We had moved much further West, through “Marble Arch” beyond the salt marshes towards Tripoli.

Enemy aircraft now attacked with machine guns and light bombs. The General’s car was hit, but no one was injured. He was very shaky, Generals Neame and O’Connors joined us at the HQ [Headquarters]. There were constant disagreements about what to do. Frustrated because of our isolation and now enormously long lines of communication back to Egypt, we dug ourselves in.

‘Rosie’ Lloyd’s brightly coloured latrine tent was torn to pieces in an air attack so was my lilo inflatable. We both felt very cross at the time.

Nearly all water points had been contaminated by bodies. A 20 mile strip of salt marshes between the desert and the sea restricted vehicle movement. Dozens of vehicles had sunk in these marshes. Old Major Hullah, our padre, kept pestering me for a map. He could not read a map – nor could his driver. I gave him a street map of Alexandria.

The following week he came back to ask for another. He had been around his parish and held a service with the “Free French”. There were no Free French within 1000 miles. These boys, he said, were wearing a grey uniform, and had given him lunch after the service, taken his map and sent him on his way.

They were, in fact, the advanced units of the German forces waiting for their tanks and field guns. Their tank commanders were being flown over our lines to become acquainted with the country.

We had now started to pull back. The last unit was the rear Divisional HQ [Headquarters]. For the next few weeks. We were only a few miles ahead of the German advance forces.

We zigzagged across the desert to lead the Germans away from our stronghold at Tobruk. Had the Germans ignored us and gone straight for Egypt, there was nothing to stop them. As it was they kept, chasing us across North Africa, up mountains and back into the desert.

The German Commander was Von Streitcher, his son was his ADC [Aide de Camp].

On these occasions his ADC [Aide de Camp] drove into our HQ [Headquarters] to ask us to surrender. Our General was very rude. The young Streitcher recognised old Major Hullah and thanked him for the church services! We were on the move day and night. In Barchi, as I was threading my way through the rubble and burning buildings and vehicles I spotted an overturned supply truck (RASC) [Royal Army Service Corps], I stopped for “supplies” there were several other lads there taking cases of tinned peaches and sacks of sugar when I noticed their vehicle. Just visible by the light of the flames was an eight wheeled German armoured car. I quietly slipped away.

[Digital Page 7]

Finally we passed back into the desert to Fort Mekili. On the way we were cut off by a mobile patrol. We had stopped on the top of a hill to erect a radio mast wired to receive instructions from Cairo. My car was about 500 yards down the hill — I had gone up to get instructions and a mug of tea. It was about midday. Reggie, the ADC [Aide de Camp], and I were enjoying a drink when a mobile machine gun opened up. Bullets flew everywhere. One hit my mug, one Reggie’s cap, I thought the hot tea on my face was blood and meant I’d been hit – fortunately there was no damage. The wireless truck was riddled but again no one was hit.

There were shell holes everywhere and we all took cover. Reggie was very upset because he had dropped his orange. Eventually I wriggled like a snake down the slope to my truck which was between me and the German machine gun carrier. I reached it safely – fortunately it started first time and I sped off up the hill and over the ridge to safety.

There was an Indian Infantry Brigade at Fort. Mekili and we were told to go there. On the way everything went, wrong. The Indians thought we were attacking them and opened fire. The RAF [Royal Air Force] made their first appearance to give us cover, but mistook us for the enemy and bombed us. The Germans, too, made a hash of things. We had stopped a mile from the Fort. Their advance units split and ran up both sides of us, then opened fire with us sandwiched in the middle. Their losses must have been greater than our own. The General or his ADC [Aide de Camp] asked for a clean hankie and got Reggie to wave it in surrender. The silence was broken by the crackling of burning vehicles. There was dust and smoke everywhere. It was 8th April 1941. I sat on my truck roof and to my surprise there was Bill in a truck a few yards away. We had not met for over two months.

Everyone was dazed – Germans, British, Indians. My Ford truck was carrying a vast amount of Egyptian money – about £2m plus all the classified documents. Bill and I piled the money into a convenient slit trench and covered it with sand and stones. I then smashed my rifle, put a packet of sugar into the petrol tank, smashed the distributor and collected some maps. Major Fordum Flower came over (he was the CO [Commanding Officer] of the Div [Divisional] HQ [Headquarters]) with G3 [General Staff Officer Grade 3] (Geoffrey Haydey Roberts) and his younger brother. They asked for maps and set off to organise a burial party.

On the retreat I had picked up a young soldier whose truck had broken down – he rode on my running board but tragically had been hit in his bottom. All I could do was to make him comfortable. By the time the MO [Medical Officer] had arrived he was dead. He had been married on his embarkation leave. We took him to the pile of bodies for burning. I had been instructed to stay with the General.

Fordum Flower was still there with G3 [General Staff Officer Grade 3] and his younger brother – I suggested that they should lie with the bodies and make a run for it after dark. It worked and they got back to Tobruk. I met them both after the war. Geoffrey Haydey Roberts became comptroten of Buckingham Palace, Fordum Flower Chairman of the Stratford on Avon Theatre – he was a brewer.

In the meantime Bill and I got into conversation with a young German NCO [Non-Commissioned Officer] – who turned out to be an architectural student. We spent a happy hour chatting by his truck which was similar to mine (Ford V8 but his had been supplied by Garwoods Motors of Toronto). Meanwhile the British Generals were being interrogated.

There were five officers over the rank of Brigadier – General.

General Sir Philip Neame VC [Victoria Cross] (Chief Engineer)

Major – General Gambier Parry

Lieutenant – General O’Connor (Tank Commander)

2 others – Indian Commanders.

O’Connor was so shaken that he took off his red tabs and stayed with the troops.

[Digital Page 8]

We were almost out of water. Eventually we were rounded up, piled into any trucks which were still mobile and made for the coast at Benghazi. Everyone was physically and mentally exhausted.

Three months earlier when we had driven through Benghazi all the houses had been flying Union Jacks. Now they all had German flags. The journey took several days. We stopped overnight by an old airfield. Bill and I with a young pilot decided to make a run for one of the Italian aircraft. We got away from our group of prisoners and hid behind a low wall by a ruined building. The aircraft was the other side about 100 yards away. After a rest we leapt over the wall and landed on a group of Germans who were brewing up. We were returned to the other POWs.

We next went by road to Tripoli and from there by train, Westwards, to a POW camp at Sabratha. Because we had been captured on Italian soil we were to become Italian POWs and were handed over into their care. There was much sickness — water and sanitary facilities were almost non-existent. We young ones were fittest; I was 20 at that time.

General O’Connor was quite poorly and decided to disclose his identity but no one believed him. He took two or three days to convince the Italian Commandant that he was a General and not a private. He was our best tank commander but, alas, had no tanks. From the Sabratha camp we could see the Roman columns of ancient Sabratha – it was many years later that my wish to visit the site came true. We drove there as a family – Olive Paul, Tim and I.

In the confusion we had all become separated. One day several hundred of us were sent in railway trucks into Tripoli.

The harbour was littered with wrecks – most buildings had been destroyed but about 500 yards off the quay stood an old cargo boat – it was to take us to Europe.

We were lined up to be taken by barge to the ship. It was noon. Out to sea we heard a bomber – a lone twin engined plane came into sight about 2,000 feet above the sea. It dropped one bomb right down the funnel of the ship which was immediately engulfed in smoke and steam and sank within minutes. There was confusion everywhere. We cheered.

The cattle trucks were reloaded and most of the prisoners set off back to Sabratha but 20 of us were left behind. Four of us, the youngest and fittest – looking were put back on the barge with some German soldiers and towed out to another ship in the harbour. It was a Polish ship with a cargo of bombs. Our job was to unload it.

The bombs were lowered onto the barge – it was in fact a flat topped lighter with no sides. There we had to lay the bombs flat with timber wedges to prevent them from rolling.

The barge was listing and there was quite a swell. When the barge rolled to port I quietly managed to loosen one of the wedges on the opposite side – nearest the ship. As the barge rolled again a whole row of bombs rolled against, the ship and one by one fell into the water.

The Germans went mad, cocked their guns and lined us up against the ship. The crew had lined the rails, yelled at the Germans and I’m certain saved our lives. I was petrified. The barge returned to the quay and we helped to unload it. It was now getting dark – I was singled out as a Sapper and taken to a bombed building where a group of German bomb disposal Sappers were cautiously removing rubble. I was put to work to help. There was a stone floor out of which was sticking the battered fins of one of our unexploded bombs. Whistles blew and

[Digital Page 9]

everyone was moved away – except the German Sapper, an officer and myself. He crawled to the bomb – I was made to follow and handcuffed to his ankle. The object was to ensure that when he reached the fuse and commenced to remove it I would understand how it should be done safely. It was about a 500lb [Pound] bomb and must have been there some time. Fortunately he did the job perfectly and we were untied and given mugs of tea. We were so relieved that we hugged each other before parting.

I can’t remember returning to Sabratha – I think I passed out. No food for two days and I was beginning to feel very weak. After two dreadful weeks in Sabratha we again were taken to the docks, but this time we were loaded into the hold of a small cargo boat and sailed out into the Mediterranean. There was hardly room for everyone to lie down. After two days the air was dreadful — we had not been given food or water and of course there were no public toilets. Most prisoners were really ill. Some died. On the third night some of us were allowed out on deck – one was a sailor who believed we were off Crete. We were each given water and a ships biscuit and those of us who were still mobile ‘were allowed out each night.

We eventually docked in Naples – by then we were filthy. Those who could still walk were lined up on the quay and we made our own way to the Army Barracks. It seemed scorching hot. We were loaded onto more army trucks and set off for the mountains. Late in the afternoon we arrived in a mountain town called Capua. It was raining. Capua is where Hannibal set up camp in his campaign against Rome. The prisoners there were mostly Australian. We were deloused, hair cut off, given food and a blanket. We were exhausted – I slept until dawn. To my surprise by midday I had found several members of Divisional HQ [Headquarters] including Bill. They had had similar experiences. A week later we all felt fitter.

As yet we had not been properly sorted out but we tended to group ourselves. Eventually the British went by train up to the Abruzzi mountains and the town of Sulmona. It was a long walk from the station to Camp FG78. We arrived late in the afternoon and all the British went to No.3 compound. The residents watched us arrive with interest. Parachutists and submarine crew with odds and sods who had preceded us. Bill and I were put into Hut 60. There were several compounds in the camp.

Senior British Officers

Officers

Sergeants

OR’s [Other Ranks]

Greeks

Free French

Yugoslavs

Sulmona is surrounded by mountains. Adjacent to our Camp was a state penitentiary (equivalent to our Dartmoor). In Italy a man may be sentenced to 400 Years, appeal and have 150 remitted. Most men in the penitentiary were lifers.

Sulmona was to be our home for the next two years. Fortunately it is in a beautiful valley – we were on the lower slopes of the Marrone mountains — the valley floor is at about 2,000 feet and the peaks reach 8/9,000 feet. At the head of the valley to the north stands the Grand Sasso – it tops 10,000 feet and is the highest mountain in Europe south of the Alps.

Our camp was actually in the Garden of Ovid’s House (he was a poet who was banished by Augustus in 23AD). He wrote the Art of Love and his villa was called Fonts d’ Amore – his fountain was our water supply.

Much happened in those next two years at Sulmona – it was like a university. Those of us with fertile minds found the days too short. We started a newspaper called “The Mountain Echo”, Bill was the Editor and one copy was hand – printed every week – Bill’s printing was superb. I did illustrations and drew a cartoon

[Digital Page 10]

strip. We had a hut reserved as a theatre and put on shows. The problem was to select plays for all – male cast so the obvious first choice was “Journey’s End”. Next we did farces. The second was “The Third Watch” in which females were not taken seriously. As more prisoners arrived in the camp so did more talent. With the arrival of Autumn so cricket merged with football until the first fall of snow. Early in December, 1941 I had my 21st Birthday and somehow managed to have a party. News of the war was bad – made even worse by the propaganda machine.

We young ones were far more resilient than the middle – aged or family prisoners. Husbands pining for wives and children – particularly when mail was bad or worse, when there was no mail at all. Again we younger ones were very fit and basic sickness never seemed a problem. We were, however, very conscious of wounded older men on the threshold of despair. Occasionally one would die. As more prisoners arrived so we became very crowded. Our simple beds were soon replaced by bunk beds and rations tended to be for two rather than for one. This began to create problems. For instance there would be one small bread roll for two every day. “Partners” had to share and rows were frequent.

Bill, my partner, and I had a fool – proof system which others eventually followed. The one who divided the roll or scup would select the smaller portions for himself. In this way we avoided arguments over food. The same applied with Red Cross Food parcels when they were distributed.

For some the nights seemed endless but again we involved a game at our end of the hut 60 where a mental arithmetic problem was circulated at dusk. Each would work out the answer for checking at dawn. An example would be “cube 738”. As time went on they became more difficult. There was little time to brood.

Life was unpleasant at times – shortage of water during the summer. The latrines were primitive and barriers tended to form between intellectual groups. Personal possessions were almost none existent – excepting in the officers compounds. The only time I really got angry was when the Income Tax returns arrived. These were the only link between our government and its men. This was my experience at that particular time. Morale seemed to be at its lowest when we lost HMS [His Majesty’s Ship] Hood, but we were surprised to receive a visit from the American Ambassador in Rome (the US was still neutral). He was carefully separated from us but he did manage to let us know he would not be seeing us again in this capacity. Shortly afterwards the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour. We were all relieved when the US decided to exclusively assist our war effort – it helped to compensate the loss of Europe, Singapore and at that time, North Africa.

We decided to organise an Art Exhibition in Compound 3 and the Yugoslavs compound. About this time one group were digging a tunnel and I managed to acquire some damp gravel. It is a natural subsoil in the mountains and when exposed to air it hardens. Romans used it for concrete. My exhibit was to be a bust of Shakespearian. It was a complete failure. The materials contained too many small pebbles and in addition it hardened too quickly. Shakespearian beard and hair fell off and by the time he had been patched up he looked like Churchill so I renamed him Winston.

Unfortunately he had just been finished and was baking in the hot sun in our compound when there was an emergency muster, We all had to line up and be counted. The Italian officer in charge was most interested in my sculpture and I was produced to give an explanation. I could not say it was Churchill but in a flash I renamed him “Il Le Duce” – Mussolini. The officer was delighted and the bust was taken to the Commandant’ s house and from there to Rome where an article in “Il Popolo d’ Italia” proclaimed it’s a work of art by a British POW.

For sometime I had been “doing” portraits, usually from torn photographs, of POWs girlfriends, wives or children. It was fun, kept me busy and acted as a cover for my official occupation drawing maps for our escape panel.

[Digital Page 11]

The Italian Captain who had discovered “Winston” commissioned me to make a portrait of himself – this meant me sketching him in one of the Commandant’s offices. It was mid – afternoon on a hot summer day, the Captain felt drowsy, took off his belt and revolver and placed them on the table. Soon he was fast asleep. It would have been stupid for me to take advantage of the situation so I quickly continued with my work. Suddenly a German staff car pulled up outside. Two German Officers and an SS [Schutzstaffel] officer jumped out and hurried to our door. In a flash I had shaken the Captain awake, buttoned his jacket, put on his belt and revolver when the door burst open and in came the three German Officers. I was sent outside but managed to snatch the Germans atlas out of their car – happily unnoticed – I hid it with the portrait and colours. A guard was called, I was returned to our compound, but I had saved the Captain from being posted to the Russian front. He was most grateful. The German visit was to enlist Italians, both civilian and army, for the Russian Campaign. I subsequently completed the portrait, made many more and became a frequent guest in the Commandant’s office.

At Christmas time I was taken down to the office under some pretext or other which I’ve forgotten, where the Captain gave me two bottles of champagne to be smuggled to the Senior British Officers so that they may drink a toast to our king.

There were many sad occasions particularly in the Yugoslavian compound where differences of opinion led to bloodshed. There were also failed attempts to escape – occasionally a death but much suffering due to an almost complete lack of medicine.

There were terrible frustrations too, lack of information, of letters, of Red Cross parcels, water and of course a mere substance diet. Occasionally we turned punishment into a game. For instance when the Allied forces made a landing at Dieppe our commandos took some prisoners back to England in handcuffs. The Italian High Command immediately issued orders for all POWs to be handcuffed. Alas they did not have sufficient. Examples had to be made so two POWs would be handcuffed together. The difficulties then occurred at night – going to the loo, sleeping and changing clothes. However a Private Horwood was an expert watchmaker — we called him “Hairspring”. By morning he had freed us all. We were to have replaced them for the morning muster in the compound but as always the comedians took over. Some appeared with the wrist of one POW handcuffed to the ankle of his mate. Groups chained themselves together others ankle — to – ankle like a three legged race. Those who had no handcuffs complained and demanded to be treated like the rest. After 48 hours the handcuffs were all taken back.

On another occasion we were all given small red patches of cloth to wear to show that we were prisoners. They ‘were about six inches square – fortunately it was in the summer. Again the comedians took over. Because there were no instructions about where these patches were to be worn – or that we should also wear clothes, most of us made them into jock straps and we all paraded in the nude. One chap, who was well endowed asked for a larger patch! One “queen” asked for two more to make a bra.

Bill and I had become excellent forgers. We had been recruited as a part of the British escape organisation. Anyone wishing to escape must first obtain permission from the Senior British Officer, give details of the plot and, if it were accepted, he would then be given whatever help was available. Clothes, money railway tickets etc.: The clothes were easy – the Camp Theatre staff could provide most things – even women’s clothes. Bill and I did the maps but we also did railway tickets and official documents. The German atlas was most useful. We would be loaned documents to copy, but with new names etc. We frequently worked all night by oil lamp because the originals had to be returned as soon as possible. From old railway tickets which would be collected from rubbish etc.; we could select similar paper, or card, someone (I don’t know who) would give

[Digital Page 12]

the current colour serial numbers and we would produce the necessary documents. As far as l knew none of these forgeries were ever detected. We even had train timetables.

One almost successful escape ended in tragedy, A young Private spoke fluent Italian. His father was a regular British soldier in Egypt, his mother Italian. He was a good — looking lad and his plan was to escape as a girl, take a train from Sulmona to Pescara. Change for Bologna, change again for Milan, change again for the Swiss border and Geneva. All went brilliantly well — he made all the connections but just outside Milan the train filled with troops making for the border and guard duty. In a tunnel, in darkness some Italian lads made advances and soon discovered he was not a girl! Apparently he had been very badly beaten and died shortly after — a lesser consequence was that he had not been reported missing.

About the same time a young Lieutenant got through to Switzerland dressed as an Italian soldier – he too spoke fluent Italian and like young Garner he too had not been reported missing. However like a fool he let it be known that he was an escaped POW from Sulmona and security from then on was really tightened up. Our Commandant at Sulmona was replaced. One other Navy POW got away to the Vatican but, apart from our later escape, we were kept under strict security. The Senior British Officers were moved and the Yugoslavs, Free French and Greeks went, too.

Most of us had made a strenuous effort to keep fit. This was not easy because of overcrowding. We managed press-ups, running on the spot, and what we called “Swedish Drill”. Unarmed combat was taught by the ex—Army heavyweight boxing champion — Norman. His partner was an Anglo — Indian boy called Frankie Hunt. Frankie was selected to play the roll of Elvira in our camp production of “Blithe Spirit” by Noel Coward. We had received the original script and some very “heavy” books on the French Revolution from HM [Her Majesty] the Queen. They came via the Red Cross. I was Elvira’s understudy but Frankie played the part beautifully. Soon the Theatre Group was rehearsing and our Company used the privileges as a cover for our escape plan. Bill and I did all the stage sets too.

At the same time we had renamed the “Camp Blightyborough”, and had formed a parliament I was elected Speaker. All sorts of plans for escape had been considered. Bill and I had been in the Camp for two years and the prospect for repatriation was about nil. Our main aim was to get home and back to the University. Some of our amputees had already been repatriated.

We had managed to get a coded message home which located our slit – trench outside Fort Mekili which was full of money, some films etc. During one of the Allied advances out of Tobruk these bad been recovered.

The war was now going in our favour and the opportunity to slip out and get away had never been better. Many had applied to the Senior British Officers for permission to escape but we were all ordered to stay put. Failure to do so would mean a Court Martial!

This was sufficient for some of us to determine to have a go! The current production of Blithe Spirit has been an enormous success. It created an illusion of stability and the privileges enabled us to prepare in earnest. Security was relaxed to the extent that we were allowed out of the compound up to the inner ring of fencing. Beyond were further rings, search lights and guard towers – but it enabled us to locate the weak spots and the surrounding cover. We made our plans.

It was late summer and we decided to go during full moon in three days’ time. Maps, rations and suitable clothes were carefully, and very secretly, at the ready. Our guards up till now had been Italian and over the months we had

[Digital Page 13]

learned to respect each other. They of course were under the direction of the Carabinieri. About noon there was a great commotion – the sound of vehicles creeping up the valley got nearer and the cloud of dust indicated they were a little more than more than 100 yards from the camp.

Bill and I were actually outside the compound when the Italian guards began to panic. Apparently the Germans were coming to take over. In fact they were mostly Poles but it indicated that security would be tightened up immediately, there was no time to go back for our “kit” — we always carried our maps and “water—bottle” with us for such an emergency.

This was it. In a flash we were over the first fence — and between the first and second fence where the guards patrolled. We darted up to the second fence and were sandwiched between the old Italian Guards and, by now, the new replacements who were running up the hill about 50 yards away.

As we got over the second fence both sets of guards opened fire. They missed us and we escaped but from the shouting and screaming it was obvious that there had been casualties amongst both the Italians and Germans. The firing stopped.

In the confusion and heat Bill and I were away up into the woods heading for the Morrone Mountains. If we had not been fit, with enormous reserves of energy, I doubt whether we should have reached the cover of trees and undergrowth. As it was we were safely through the wood and heading for a tree lined gulley. At about 2,000 feet above the camp we looked back. We were exhausted but free!

The next phase would be across a rock face but danger of detection was not worth risking. We were on the West face of the Marrone range and would be in bright sunlight until sunset. The opposite side of the valley, beyond Sulmona, was already in shade. We rested under the ferns shaded from the sun. At times like this we agreed that as one rested the other would remain alert.

Towards evening we moved onto the rock face and made our way up to the grassy slopes along the top. There were some sheep there so we assumed that there would also be a shepherd too. We also noted a further ridge of peaks in the moonlight. The going was difficult and our progress was slow. Next morning the search parties would be out so the greater the distance between the camp and ourselves the better. Our original plan was to make for Switzerland. Our maps were for the North but although we were heading East, we were still on the maps. As dawn broke we had crossed the second line of ridges and were heading across a grassy slope towards the third ridge. We were well above the tree line – at about 5,000 feet. The tinkle of sheep bells drew our attention towards the flock with three human figures. Cautiously we made our way towards them.

One was an old shepherd, one a young priest and the third an Italian youth from Rome. They seemed to know we were escaped prisoners and seemed relieved to meet us. They had a strange tale to tell. The youth was a Carabinieri sergeant under sentence of death and the priest, Geraldus, had been sent to administer absolution. However he was armed and the two of them had got away to the mountains and were heading towards a remote village called Salle. The shepherd was helping them across the mountains – we were invited to join them. The priest in this remote village was a friend of Geraldus and we could hide up there. The old shepherd took us to a spring where he filled our water bottles before hiding for the rest of the day – there was no cover so it was essential that we should move only at night.

The spring was still visible below us. To our horror several figures appeared below and made for the spring; a German patrol. They were hot, tired and like us rather scared. We were light, they had steel helmets, rifles, kit bags and ammunition. They also had food! The shepherd was still with his sheep on this

[Digital Page 14]

high grassy plateau. One of the soldiers spoke to him but he did not give us away between sunset and the rising moon we silently crept towards the summit. Going up is always easier than descending but with the aid of the moon we made better progress. Our plan was to reach the tree line before dawn. Also our descent into the next valley would take us several days. We continued to move only at night but as Geraldus predicted there would be no soldiers on this side. The village to which we were heading was called Salle. It was now visible on an outcrop of rock 2,000 feet below us. Geraldus left us in the morning to make his way down. In the late afternoon he returned with a Woodsman with some bread and cheese. It was a banquet.

In this part of Italy there is no coal so the beech forests are harvested for distillation into carbon. During the summer men and boys from the valley work in the forest producing carbon and on the lower slopes caring for the sheep. During winter the mountains are in deep snow so the men and boys drive the sheep south from the mountains to graze in the pastures around the plains of Foggia. The women and children remain in the villages to look after the lower fields, vine yards and live stock. This had been the pattern for generations.

Our woodsman’s title was La Guardia and he was in charge of the forests. He lived in Salle, knew the priest Don Oliverio and was to prove to be a loyal and generous friend. Next day we were led into the upper part of the forest to a hut in which the carbon workers had lived during the summer. It was now empty but offered tine luxury of a roof. Don Oliverio visited us next day with Ermenia de Monte. They were loaded with supplies – bread, cheese, grapes, soup, and wine. Ermenia was a tower of strength – she lived in Salle and had enormous energy. They had travelled over five hours from Salle up steep paths through the forest. They also had news. The Allies were to land at the top of Italy so if we stayed put, we should soon be behind our lines – our plan to head North to Switzerland was then abandoned.

Geraldus and the Carabinieri had moved on to another village where the boy would be safe. We never saw them again. One day La Guardia brought in three other escaped prisoners from our camp – two soldiers Geoff and Dai Jones and a young British officer, Ken. By a wild coincidence we all came from the Wirral. We were assured that there were no Germans in this valley — or in this part of it, so we moved lower down to the fields above the village of Salle. There we helped with the harvest. Salle consisted of two villages. The old village had been completely destroyed during an earth quake and the Government had built a completely new village, two miles lower down the slope. This village had water, electric and modem sewage systems. It had been completed by about four years before the war. It was a model small industrial village whose main business was making violin strings from sheep gut. The gut was dried, cleaned, twisted and stretched to produce a range of thicknesses. It was a smelly place.

One day there was a panic. The village was to be occupied by a German patrol — we retreated back up into the mountain. The German Commander instructed the Mayor to provide “girl” escorts for his troops. Immediately all the local girls were sent by their parents to join us in the mountains. About 20 arrived one night with La Guardia – and placed in our care. The problem was to keep them quiet – sound carries a long way in the mountains and this was their first experience of mixing with Foreign soldiers. Their stay with us was only to be temporary whilst their families made arrangements for them to to billeted with relatives in other unoccupied remote villages. Within three days we were alone again – however the Germans had been alerted that we were in the region.

It was now late Autumn. One day La Guardia came up with three more soldiers – two NCO’s [Non Commissioned Officer] and an Irish Captain. He was a doctor. They were heading South. The Allied Landings in the North had not taken place – they were now expected to land in the South. The weather was turning cooler and the sheep were being gathered

[Digital Page 15]

in the valleys before their long journey south to the plains of Foggia. The head shepherd in the valley was a tough old man called Bartolomeo. The last of the harvest had to be gathered in and we all helped in the top fields just below the tree line. Bill and Ken were hidden in the town having medical treatment. The priest’s mother was the nurse. The rest of us remained with the harvest.

At midday we stopped for our usual meal of pasta when quite unexpectedly three men appeared. One was obviously an Italian peasant, but the other two were sportsmen out on a shoot. They had sporting guns and were quite out of place in “our” valley. No local men would have the equipment which these two had. We welcomed them all and invited them to share our meal. In the normal course of events an Italian peasant would not presume to be their equals. The two sportsmen were, to me, obviously German Officers having a days relaxation with their guns. The Italian peasant knew we were not Italians by our accent, but I doubt if the huntsmen were sure. They were however suspicious. The Irish Doctor could not resist examining their guns – he handled them expertly. The Germans were alarmed and offered to leave three game birds in repayment for the pasta, grapes and wine. One of them asked the doctor where he shot and the fool told them! They exchanged shooting experience and promised to meet him in Ireland after the war.

The cat was out of the bag. They prepared to leave, thanked us and made their way back down the hill. Before they were out of sight I had collected my belongings, bid the others a farewell and keeping well out of sight, followed the shooting party towards Salle. The doctor was quite oblivious that he had given the whole game away by telling them he had a shoot in Donegal. Geoff and Dai packed but made their way back up to the mountains to hide. I hid in the ruins of Old Salle and waited. Within half an hour a German armed patrol left Salle heading for the mountains. There was an interval of about an hour – about the time to reach our fields, when the sound of gun fire closed this episode. I don’t know what happened but the three who had decided to stay put were never in contact with us again. I made my way into the new village to stay as near to the German’s base as possible because they would now be out combing the mountains looking for the rest of us. It was dark but I knew of a semi basement which was used as a farm store — it contained hay, was reasonably dry and clean. I fell asleep but was awakened at dawn when the door creaked open and a small girl came in looking for eggs. Hens also shared this room with me. Soon she would find me under the hay so I decided to make the first move and hoped that she would not be too scared. Very quietly I whistled a tune from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”. She stopped and listened, then I said “hello!” and asked her name. She told me and I asked if she could whistle too — she, shyly, joined me in a duet! She knew I was an escaped prisoner hiding from the Germans but others in the village knew also of us and accepted us as friends – but they never knew where we stayed.

The Germans had by now an accurate description of me because I had been the spokesman over lunch. My Italian was far from being polished – my accent must have been terrible because of the way I learned to speak. This must, have temporarily fooled them. Back in the POW camp many of the Guards could not read or write – I could read but did not know exactly what I was saving. The guards would hand us letters and newspapers to read, this we managed to do but they corrected our accents. By comparison my Italian must have sounded like someone from the back streets of Naples – or Birmingham. I asked the little girl to take my clothes to Don Oliviero and asked him for replacements. She agreed. I stripped off and returned below the hay. She left with her eggs and my clothes over her arm. In order to make the exercise into a sort of game. I drew a series of cartoons:-

One showing her and me dressed;

One showing her, but me undressed – she had my clothes;

[Digital Page 16]

One showing her with Don Oliviero – giving him my clothes;

One showing him giving her new clothes;

One showing her returning to me; and

Finally one with her and me, in my new clothes.

Don Oliviero kept this drawing and years later after the war when we returned to make a BBC programme he produced this old scrap of paper from the church records. I had hoped that my new clothes would come “by return”, but alas, two days passed without a visit from the little girl. All this time the Germans must have been scouring the mountains for me. At last one morning I heard the door creak open and the little girl came in – I sat up to welcome her but to my horror she did not have my new clothes. At first she pretended not to understand me but eventually burst out laughing and ran outside. She then returned with “things” for me to wear so I dressed as quickly as possible. The little girl had done her job perfectly – although it had taken some time. I was desperately hungry – it was darkish and getting cold. The good news was that the Germans had left the village, so I cautiously made my way up to the Church. Bill and Ken had been hidden there the whole time and were now almost recovered. Both had had a series of boils which were leaking and very painful. I was very fit.

The main businessman of Salle had a friend who was the Mayor of Pescara – a large town on the Adriatic Coast. His brother was the Mayor of New York. For some reason or other the Mayor of Pescara wanted to meet us. We were washed and shaved and taken to a large house in the Village Square. It was sheer luxury being clean and in civilised surroundings, I had expected the Mayor to sneak in the back — as we had done, but no, he arrived with a police escort. His car was a Buick Limousine which must have been a very conspicuous vehicle in a remote mountain village. Apparently, so we were told, a submarine was to pick us up on the Adriatic Coast – Italy had surrendered and everyone was hoping for an Allied landing. People started to take risks – they certainly nailed their colours to our mast. The Allies missed a wonderful opportunity at that particular time to take Italy, but alas they allowed the Germans to occupy the whole country. After a lovely meal we parted and agreed to meet again. The Mayor’s convoy left for Pescara with it’s escort. By a strange chance Don Oliviero was later to become the Bishop of Pescara.

Years later when I was a student in New York the Mayor, La Guardia, had died and I attended his funeral in St John the Divine Cathedral. I did not meet his brother from Pescara – perhaps he did not survive the heavy fighting. Hundreds of thousands of New York Catholics had filed passed La Guardia’s brei as he lay in state. Normally his funeral would have been in St Patrick’s in down-town Manhattan, but it would have been too small.

The Mayor’s visit to Salle again alerted the Germans that prisoners or someone important were in the region. Bill and Ken retired to their hiding place and I to my hens in the hay rick. Next day, at 2pm, I was in a village house waiting for the BBC midday news. A play was just finishing — “The Monkey’s Paw”. I wanted to check details of landings etc.; and had my maps laid on the table. Yes, the Allies had landed in Sicily, but not yet on the mainland. At that moment the alarm went up. The Germans had returned to Salle in force!

If a POW was found in a house, it was immediately burned down and the owner shot. My thought was to protect my host – the wife of a Cavalry Officer. I grabbed my maps (now in the Imperial War Museum) and ran out into the street. At the same moment a truck load of troops turned into the same street about 100 yards away. In a panic I dropped the maps, stooped to pick them up and noticed they had fallen onto a manhole lid.

In a fraction of a second I had lifted the lid and climbed down. It is surprising how quickly one’s mind can react and adjust to situations. It was the

[Digital Page 17]

main village sewer. The village was on a steep slope – the 18 inch oval sewer pipe entered the manhole at the top and fell down about ten feet to the outfall at the bottom. I knew that if I had gone up the “in” pipe head first I would drown. By going head first, with the sewage, down the outfall I had a chance – all this had only taken seconds. As I headed into the pipe the sewage crept up my trouser legs, over my shoulders but at least l could breathe. In fact I was actually floating down the pipe like a cork.

There was a tremendous explosion – I can only assume that they had dropped a grenade into the manhole to finish me off. As it happened it propelled me forward in the blackness. It was like being a bullet being fired from a gun. I must have passed out. I could still breath, just, and on I floated down. It was too tight for me to move – fortunately it had been raining and there was just enough water to float me on. In a dry sewer there would be no chance to move one way or the other. I remember reaching a reinforcing rod across the pipe and I had great difficulty squeezing past. To go back would have been impossible. Eventually I reached the next manhole and hung out of the pipe like a worm. The sound of water tumbling down to the bottom brought me back to my senses. My arms had been stretched out in front. Now they felt for the rungs which are built into the walls for access up and down.

Somehow I managed to hold on to prevent a fall to the bottom – I was still blown up like a saturated bag. My feet felt for the rungs and took the weight off my arms. I climbed up to the cover and with my head and shoulders gently lifted the lid off. It was then pitch black, and raining heavily. I must have been in the sewer for seven or eight hours. A man who was walking past looked in horror at me and fell on his knees in prayer — he must have thought I was the devil. He informed me that the Germans bad gone so I made my way to the house with the radio. The situation for these wonderful Italian women was now very difficult because the Germans were alerted to there being escaped prisoners in the area and in the village too!

Don Oliviero called so did Ermenia. I was cleaned up and fresh clothes were produced – these consisted of an old dinner suit and sweater. My boots were badly cut by the fragments of hand grenade and bits of sewer pipe but mercifully apart from flesh wounds no bones appeared to be damaged in my feet. The real worry to me were the numerous punctures in the flesh around my groin – the bleeding must have kept the infection in check. An old lady made a dressing of herbs and white of egg. She had been treating Ken and Bill with incredible success. They had managed to slip out of the village during the commotion by the manhole incident arid had been bricked up in a cavity in an old stone wall on the mountain track.

It was now impossible for any of us to stay in the new village so about midnight I set out in the pouring rain for the mountains. All our friends were in tears. The track to the mountains went through the old village which was about two miles away. Rain water was flooding down the track like a river. Above the noise of the rain and wind a sound of approaching footsteps got nearer and nearer. I hid at the side of the path when two figures appeared under a huge umbrella.

By an incredible stroke of fortune it was Bill and Ken. It was indeed a joyous meeting. We figured that the Germans would be out again at first light to scour the mountains so we decided to hide in the deep gorge below the new village of Salle. The rock face on either side of this gorge was vertical and the river would by now be a raging torrent. We could not get wetter so we made our way down to the gorge. We waded down the river to a small dry crevice in the rock and settled down for two days for the Germans to tire of looking for us.

On the second day the rain stopped and a warm sun soon dried our clothes. A girl from the village came down with some washing – we knew her to be trustworthy and

[Digital Page 18]

disclosed our hiding place. Later in the afternoon Ermenia came with some pasta and wine. My feet and groin were very painful and I had difficulty walking. She told us that La Guardia knew of some hidden cellars in old Salle where we would be safe so at night we were led into the old ruins. It was a maze of narrow alleys between wrecked buildings but there were many cellars – we made ourselves familiar with the suitable escape routes in the event of being disturbed.

The following day we were stunned to see a German patrol moving up the mountain about 50 yards from our path. They had heavy machine guns and mortars. They did not return that day. About 4am the following day Ermenia crept into our cellar – the Germans were to search the old village and had posted sentries on the paths leading in and out. She was a real heroine. The usual way in which the Germans rounded up workers, or prisoners, was to post sentries at night on all paths and roads leading into the village, then someone in the centre of the village would fire off several bursts of a machine gun to waken everyone and create panic. All those who should not have been there would try to escape by running out of the village where they would be rounded up by the sentries. At dawn we could see them – fortunately there were only half a dozen but they had rifles, helmets and lots of equipment. They were far less mobile than we were and they were perhaps even more scared. There was the usual burst of machine gun fire but quietly we stayed put. The Germans then came in to do a search. For a whole day we played cat and mouse.

Towards evening they gave up and went back down the mountain. It was obviously too dangerous to remain near to either the old or new villages. So we made our way again up to the Carboni huts. We travelled separately at intervals. On the way we passed the German mountain patrol on their way down. They were worn out and looked completely fed up.

At about that time there must have been many groups of prisoners on the mountains, A group of Free French whom we met had arrived and had threatened to kill Germans wherever they found them. This upset Bill and I and we were delighted when they moved on towards the North.

We made our way to a remote hut in which we had sheltered some weeks earlier. To our horror there were two young German lads there with their throats cut. One was dead and the other was barely conscious. In the cold, his blood had congealed into a solid mass and this forced him to gasp for breath. Bill cleared his windpipe so that he could breathe more easily but it was too late. I sat with his head in my lap, our eyes met and his – and ours – filled with tears. At least he died with friends.

It was obviously far too dangerous for us to remain there – soon colleagues would be out to look for the missing lads – when they found them all hell would he let loose. We covered them with leaves and branches and soaked in human blood we made our way back into the forest. It was pouring with rain.

At day break to our delight we again met Geoff and Dai together with three other ex-POWs. They had planned to stay put in the mountain until our forces occupied the valley. La Guardia had also been providing them with food but there were now too many of us. A trip to the village and back would take at least ten hours. Ken, who was the only officer, felt he had to take charge of us and for two or three days we agreed to comply with his leadership. We fed off sheep.

We were then high up the mountain at the top of the tree line when the first snow fell. Our options were either to remain in the snow where our tracks could be easily followed or we could move down deeper into the forest – but nearer to the village. Bill caught another sheep which we killed and skinned for our last meal. We had learnt much from the shepherds. Bill, Geoff, Dai and I were prepared to eat raw fat and lard. The others wanted to cook over a fire. This

[Digital Page 19]

was our signal to part. The smoke would give our position away but they would not listen.

We four then packed and made our way South. The others remained — or so we thought. We believed the road to the South at the top of the valley would be too heavily guarded so we decided first to move across the next mountain range to the East towards the Adriatic and then more South. This is the Miella range and the second highest south of the Alps. That night we crossed the river in the gorge below Salle and made our way up the other side towards the small town of Carramanico. We spent the day hidden in undergrowth, crossed the main road between military convoys which were moving both North and South.

By dawn we were high in the forest, on a path which led to Sana Spirito. This is an old 5th Century monastery where Fra Diavilo had lived (he was the Robin Hood of Italy). My feet by then were giving so much trouble that I could only hobble – they also were so swollen that I had to travel bare foot once we reached the snow line. The intense cold stopped the pain. When we finally reached the ruined monastery we found it occupied by the survivors of a Canadian Bomber. They were well – equipped and had travelled about 50 miles from where they had landed. They also had – up – to – date news from England. The Allies had decided to fight their way North up the leg of Italy. The Americans on the Rome side – they were then bogged down at Monte Casino, and the Brits up the Adriatic Coast.

I slept soundly in a cell overnight. Outside there was a blizzard raging. The Canadians kindly tried to dress up my wounds but the cold had reduced the swelling and the pain was much less too. Somehow or other they had a German doctor as a hostage and he removed the obvious bits of stone and metal which had worked its way to the surface. Again we four felt that there were too many of us so we moved off at dawn up the valley towards a saddle between two ridges. The going was difficult because the freshly fallen snow was soft and by then was over 2 feet deep.

By mid – afternoon in brilliant sunshine we reached the saddle. I had found it easier to crawl on my hands and knees. Suddenly Bill sounded the alarm – up on the West ridge about one mile away was a line of four skiers – obviously German and were already heading down our way. We later found out that they were from a German ski school on the Miella. We moved forward as quickly as possible and made for the steepest downhill slope. Below on the Southern slope lay the top trees of a pine forest. We lay on our tummies and “swam” towards the pine trees. Dai was leading. We must have been doing 8/10 miles per hour by the time we reached the trees – their lower branches were already buried in the snow and reached the snow covered ground. We slid into the trees head first and kept going when we heard screams and the cracking of branches and skis as the Germans hit the trees. They must have almost been on top of us. Then there was silence apart from the groans of their injured.

Three of us had stopped, but Dai had difficulty and headed beyond the trees towards a precipice. By a stroke of good luck he was able to grab a bush at the very edge. We formed a human chain and very carefully pulled him back. The drop was about 1,000 feet. It was now getting dark and we were about to dig sleeping holes in the snow when Geoff spotted a new track made by some animal – possibly a wolf or fox, which seemed to lead down. We followed it into a clearing where exhausted, we dug two holes. One for Bill and I and the other for Geoff and Dai.

It was bitterly cold but the snow must have provided some insulation. Our sleeping pattern was simple but effective. One would curl up on his side and go to sleep. The other would wrap himself around facing the same way but would keep awake. The main heat loss would be from his back – this would keep him awake and alert. When the cold became unbearable he would turn over curl up and go to

[Digital Page 20]

sleep and the first chap would wrap himself around the sleeper and “thaw” his frozen back. Before dawn we were all awake and ready to move on down the mountain to the South.

About mid – morning there was the rattle of automatic weapons from above us in the mountains. We did not know it at the time but apparently Ken and the others had decided to follow us but had been caught by the ski patrol. Ken was the only survivor. When we met, years later, he told me of this tragedy. He spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp.

Later that day we could hear the noise of battle ahead. We were nearing our lines! Geoff was near to exhaustion and he and Dai decided to move more slowly than Bill and I so we parted at about 5,000 feet. Dai’s book “Escape from Sulmona” covers his experience from then on.

Geoff decided to go down to the nearest town for medical help. He was retaken by the Germans and spent the rest of the war in a POW camp. He survived the war but died shortly after.

Dai decided to go North again and spent many more months on the run before he too was reached by our forces. Dai died sadly in 1988.

Bill and I decided to continue South at about 3,000 feet. All the time the sound of gun fire got nearer – or we got nearer to it. One day we saw three figures climbing out of the forest into the snow covered plateau where we were walking. They were two British Officers and an elderly doctor – I think he was a major.

They too were heading South but the lower slopes were swarming with Germans and they felt it to be too dangerous. It was now almost dark and Bill and I prepared our snow — hole. Our advice to the three new — comers was to do the same – but in one big hole. For some reason, perhaps modesty, they all settled in separate holes.

As usual the night was bitterly cold. Bill and I were awake as dawn was breaking and went to raise the others. Sadly the Doctor had frozen stiff during the night – it must have been a painless death. The two younger ones survived, just, but were suffering from frost bite. We managed to restore some circulation but both were in agony. Their only hope was to get to hospital as quickly as possible. The last we saw of them was stumbling back to the woods. I don’t know what happened to them. We covered the Major with snow, said a prayer, and set off on our way.

Lower down we heard some sheep and once more we enjoyed a meal of raw fat – it kept us going. Most of the sheep had ticks so the fleece was discarded as soon as possible. Below us in the valley we could see the River Sangro. It was obvious that the Allies were on the other side – we could see gun flashes from both sides. It was an ideal spot from which to watch a battle but we had to keep moving. We made our way below the snow line into the forest and dry land. I managed to fit the remains of my boots once more onto my feet. One of Bill’s boots had almost disintegrated. We could hear the roar of heavy traffic on the road below. Although we were always cautious for some reason or another that day there was a feeling of elation. We were still alive. The slope was grassy and the trees had thinned out considerably – we started to jog downhill.

Out of the scrub about 50 yards below us four young German lads were sitting down – we tried to stop, but only managed to slow down. The Germans turned saw us and fled down out of sight. It was only now that we realised how terrible we must have looked. We had three weeks’ growth, filthy clothes soaked in sheep’s blood and had sticks which might have looked like guns.

[Digital Page 21]

Soon we found a safe hiding place until it was dark – from now on we would only move at night. We reached the road at dusk and remained hidden whilst a convoy of tanks made their way down the mountain road towards the front. On the opposite side of the road was a low stone wall – at a convenient gap in the traffic we darted across — vaulted over the wall and fell about 10 feet on to a ploughed field. It was a miracle that no limbs were broken.

The ground was a steeply sloping field but we did not realise at the time that the mountain road zig – zagged down the lower slopes with numerous hairpin bends. We must have crossed the same road four times before arriving on level ground in the valley. Soldiers on the trucks all seem to be singing a German version of “Roll out the Barrel”. Trudging across ploughed fields was exhausting. Our feet were constantly caked in mud and they felt like lead weights.

We tried to keep quiet but every dog from miles around seemed to be barking. Soon it would be dawn and we needed shelter during the day. Ahead was a hillside graveyard with convenient tombs. One had a broken slab and we were able to creep inside for a well — earned rest.

British artillery shells were now passing overhead so we assumed our lines would be about four miles away. At dusk we were on the move again but we were now too low to see the flashes so navigation was hit and miss. Bill tended to lead but about midnight I took over to give him a rest. It was pitch black and raining when we encountered barbed wire. Mine fields never crossed our minds.

Eventually whilst half way across a barbed wire fence we heard a frightened voice enquire “Karl?”. We had broken into a German Cookhouse and the guard or cook must have thought we were colleagues. We froze and very slowly and quietly retraced air steps to safety.

The next day was spent in a ditch but we did manage to see the road leading to the bridge. At night we made our way to the river bank but to our horror the bridge had been blown up. Hurriedly we retreated to seek shelter before daybreak.

In this part of Italy hay stacks are usually in light reed buildings with thatched roofs. They are quite comfortable. The farms around Salle consisted of no more than two rooms. One was for the parents and the babies, one for the daughters. The sons lived in the hay stacks. We came across a typical small farm with two or three small fields and the usual hay stack. Seen we were under the hay – it was the first time we had enjoyed warmth for ages. We made a small dug out for added protection. I slept all day.

At night we crept out and approached the farm. The old farmer and his wife were very friendly – he had worked as a labourer on the railways in America so we told him we were Americans. He was delighted and soon we were enjoying a large basin of potato soup, bread and wine. He had three large vats of Marsala — a rich red local wine. We all drank our fill.

We did not tell him where we were staying, for obvious reasons, but were invited back next night. During the day we could look out and see a platoon of Indians attacking a German outpost on our side of the river. The constant sound of gun — fire was deafening. That night we returned to the farm but had rather more wine than was prudent. We had also seen, during the day, a larger farm which was being used as a billet for the German soldiers. We quietly made our way there, inside we could hear German voices so we banged on the doors and windows and yelled for them to come out. They all went as quiet as mice, so we returned to our haystack feeling very smug, Our confidence was growing — the German lads seemed more apprehensive now that shells were constantly whistling overhead.

[Digital Page 22]

The following morning Bill went to his usual position at the edge of the haystack to scan the countryside. He whispered for me to join him. Between the river and a small town on rising ground behind us were open fields (the town was Guandiagrele).There were one or two scattered farms and barns and all the trees were bare.