Summary of Des Jones

Des Jones, the founder of the Army POW Escape Club, recounts with much vivacity some 50 places he passed on his way from Milan to cross the front line. Originally having escaped over the barbed wire just before the Armistice was announced but then being recaptured, he had to, twice more, escape the clutches of the Germans before being on his way. Des’s original companion, Johnny Gallop, cried off because of appendix pains but still made it to Switzerland before having it removed.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital page 1]

[Cover Document with brief introduction]

Des Jones, the founder and kingpin of the Army POW Escape Club, in his account lists some 50 places he passed on his way from not so far south of Milan to cross the lines near Frosinone less than 2 months later but after some 1000 foot kilometres – only 70 of them by train! On the tracks, much worn [Word redacted] by POWs around Bardi, Des found the notice which valued him at £20 as a reward to Italians who might betray him or any other POW, Des had originally escaped over the barbed wire just before the Armistice was announced but being recaptured had to, twice more, escape the clutches of the Germans before being on his way. Des’ original companion, Johnny Gallop, cried off because of appendix pains but still made it to Switzerland before having it removed.

[Digital page 2]

[Text overwritten] Des Jones life up to departure for Algerian landing – where later he was captured.

[Text continues]

Foreword

Two people who volunteered to read and comment-on the following literary masterpiece both made the same suggestion – that I should write a ‘foreward’, telling something of my own background, instead of just kicking-off half-way through the war, so, blame them for the following seven pages of childhood and other memories. I shall skip the measles, mumps and other illnesses because I can’t spell peritonitis.

My father, Jack Jones, who was born on the 17th October 1894, was one of three children from a poor family. His father was a labourer with Swansea Corporation who spent most of his adult life helping to maintain the town’s sewers. Jack left school at fourteen and became a messenger boy with the Post Office. During WWl [World War I] he joined the R.A.M.C. [Royal Army Medical Corps] and one of his favourite jokes was that the letters stood for ‘Rob All My Comrades’. However, he was so religious that he would never have done such a thing.

My mother, Maria Thomas, was born in Aberdare on the 9th September 1891. In 1895 her father became Foreman of Works at the Castle, Cape Coast, West Africa where he applied for a permanent post. In 1896 he was awarded the Ashanti Star. Meanwhile, his wife, Kate, remained in Aberdare with their two young daughters, my mother and her older sister, Margaretta. Grandma Kate died at the early age of 30 on the 16th April 1896 and her daughters were cared for by relatives. Grandad Morgan Thomas remained in Africa until shortly before his death on the 20th May 1907, age 39. He is buried in the same grave as his wife in Aberdare cemetery.

My father and mother met whilst she was working as a shop assistant in a department store in Swansea and they were married on the 3rd October 1917.

My brother, Alan, was born on the 6th August 1918 whilst my father was still in the Army, but died six months later on 3rd February 1919. Then I was born in Swansea on 4th November 1920. My mother died in hospital five days later, on the 9th November, age only 29 years. She is buried in Mumbles cemetery.

At the time my father was living at 5 Devon Terrace near the sea-front in the Mumbles. By this time he had become a sanitary inspector with Swansea Corporation and employed a middle-aged lady named Sarah to look after me whilst he was at work.

But my mother’s sister, who lived in Cwmbach, had always disliked my father (possibly with good reason) and one day came down from the Welsh hills and took me away. Sarah informed my father who hired a taxi and, accompanied by a Police sergeant, covered the 25 miles to my aunt’s house in record time and took me home. He did not take any legal action against her but the feud lasted for as long as I can remember although I was allowed to stay with my aunt for a week each Summer.

[Digital page 3]

After that incident, for security reasons, I went to live with Grandma and Grandad Jones at 21 Carlton Terrace, Swansea. This was a terraced house with a back yard which was surrounded by a brick wall and, apart from the occasional visit to the town or a park, I had no contact with other children of my own age for over three years. I was brought up in a wholly adult atmosphere. Also living in their parents’ house were my Uncle Sam and his wife Mabel, and unmarried Auntie Di (somehow short for Emma).

On Saturdays a well-dressed (he wore a white collar and a tie) man used to call and take me for a walk. This was, of course, my father, although that meant nothing to me at the time. On one occasion he somehow managed to break my arm although this was probably my fault because I was very spoiled and always wanted my own way.

In his youth Grandad Jones, who was born on the 18th October 1862, had been quite adventurous. After his mother had died, he couldn’t get on with his step-mother and had run away to sea at the age of fifteen as a cabin boy and had sailed around Cape Horn in a windjammer. So, at bed-time he used to tell me tales of the sea; about dolphins, sharks, terrible storms hundreds of miles from land, with the tips of the masts touching waves as high as houses, and about strange people who lived on the other side of the world. Even though the same stories were repeated time and time again I never tired of them.

Then before 6am we got up and checked the mouse traps and the cockroach tins. The latter were about ten inches in diameter with small rotating tin blades built in to the open tops. I can’t remember how, but somehow, the cockroaches were persuaded to climb up the white, curved side of the trap and step on a tin blade which would rotate under the weight and drop the little black beetle into the tin. Having lit the fire in the old-fashioned, black-leaded grate, Grandad would then remove the blades and empty the contents of the traps on to the fire where they would sizzle and explode. The mice were usually thumped on the head with a poker and flushed down the lavatory. This meant a trip into the yard, whatever the weather, because, like most terraced houses in the 1920s, the lavatory was in a wooden shed at the bottom of the yard or garden. Which accounts for the importance of under-bed chamber pots in those days.

When I was naughty Grandad used to tell me that I took after the ‘Irish tinkers’ in the family but, because of inadequate records, I have never been able to find out who they were. Did they come over at the time of the potato famine or were they, perhaps, earlier refugees from Cromwell? So I don’t know if I am actually descended from some itinerant Mick, or was it just the case of an Irish gypsy colleen marrying a cousin, fifty times removed; a sort of distant twig on the family tree?

When I was exceptionally naughty the ‘Man with a sack over his head’ used to appear and give me a lecture. I didn’t realise it at the time but it was Uncle Sam with a sack over his head and shoulders, so he had to be guided into the room. He used to frighten the life out of me, and the threat of a visitation was usually enough to make me behave. For a while, anyway.

[Digital page 4]

In 1924 my father married a young widow, Dorothy, who had woken up one morning and found her husband dead beside her. I went to live with them at Maes-y-Bryn, 2 New Villas, Mumbles, which was in open country near a farm; a much nicer area than Carlton Terrace. At last I had a playmate, a boy of my own age, who lived a few doors away. As we got older, on Saturday mornings we joined the small crowd (all ages) outside the farm slaughter-house, a tin shed on the corner of the road, to watch the slaughterman cutting the throats of pigs and other animals. They used to leave the double doors wide open so that we got a good view. The sounds of slaughter could be heard for miles but, in those days, were accepted as part of country life.

Like Grandad Jones I did not get on with my step-mother, but was too young to run off to sea. I’m sure that it was mostly my fault because I was so spoiled. When my half-brother, Norman, was born in 1925, I felt as though I’d became almost invisible as far as step-mamma was concerned, except during ‘ear-clipping’ sessions.

That was the year I started at Oystermouth Council School. So, what can I remember about the ‘Roaring Twenties’? Well, there was the widespread unemployment, especially during and after the General Strike. This was particularly evident in the small mining villages, where I had relatives. Bands and orchestras playing nice music, including the old WW1 tunes, on the Mumbles Pier and in band-stands on the sea fronts and in parks. Two minutes of real silence on November 11th with even the buses and other vehicles stopping on the first stroke of eleven o’clock. Horse-drawn carts and cabs. People standing-still respectfully and the men removing their hats when a funeral procession passed. Motor vehicles being cranked-up with starting handles because they were not fitted with self-starters. Tramps (and others) picking up discarded cigarette-ends from the pavements and putting the tobacco in small tins, and ex-Servicemen, who had served in France, calling each other, ‘Pal’, as they had done in the trenches – a reminder of the ‘Pals’ battalions which were recruited locally in towns and cities during WW1. I could go on and on, and if I started on the ‘Thirties’ wouldn’t know where to stop.

In the 1920s Welsh boys used to take swords and shields to school on March 1st, St. David’s Day. We couldn’t get to school early enough to start the sword-fighting, which was continued at play-time, dinner time and on the way home. Pointed swords were confiscated by the teachers but some were less blunt than others. My father made me a large, ply-wood shield with a black cross on the front, and a 24 inch-long flat, wooden sword with a rounded end, with which I battered every other sword-bearer in sight.

As I got older, step-mamma started to regard my bedroom as a no-go area, and who can blame her! First, there was Captain Bones, which was an African skull (a legacy of Grandad Thomas). I had wired torch bulbs into the eye sockets and made a ‘body’ out of a black skirt draped on sticks with black silk stockings for his arms, and white gloves for hands. The eyeball lights were operated by a small torch battery which was also connected to a small buzzer. If anyone stepped on the mat inside my bedroom door, the skull’s eyes lit up and the monster buzzed.

[Digital page 5]

[Photograph with caption] Captain Bones playing an African tom-tom. Enlargement of a snapshot taken with a Brownie box camera circa. 1932.

[Digital page 6]

She was also put off by my collection of Red Admirals, Peacocks, Fritillaries, Tortoiseshells and other butterflies which were impaled on pins on boards, hanging on the bedroom walls. And occasionally I’d keep a large glass jar of wriggling tadpoles in smelly water on my bedside table, waiting for them to grow legs, which they often did, and change into frogs, which they never did. But what no-one ever saw was the large, well-concealed, sweet jar which sometimes housed a grass snake or two in grass and leaves. Once I even had a ‘pet’ viper, but it was a little bit vicious and, probably fortunately for me, it soon died.

Other unwelcome ‘pets’ were the bats which my friends and I used to collect from a cave near Limeslade Bay and let loose in such places as the Methodist Chapel which we attended on Sundays. That was before I was blackmailed into becoming a Sunday School teacher. Some kids are horrible and I think our little gang were more horrible than most.

I failed my ‘scholarship’ but my father paid £12.50 a year for me to go to the prestigious Swansea Grammar School. Some of my class-mates and friends were later to get killed during the War. One unforgettable character was an English master, Archie Maine. As we walked down a corridor between classes Archie would be standing there, clutching the lapels of his gown, smiling. Then, for no apparent reason, he’d point at two boys and say, ‘My room at twelve o’clock’. We dare not disobey and soon after twelve o’clock we’d be bending over a desk for three, four or six whacks with his cane. In between each whack he’d give a little lecture on behaviour. It was his way of teaching discipline and was obviously approved by the headmaster. I believe that we could do with an Archie Maine in every school today.

Another master of note was ‘Old Man Thomas’ who was poet Dylan Thomas’s father. He taught English Literature and really hammered poetry into us. So much so that, at 75 years of age, I can still recite about six of his poems without hesitation. His favourite theme was (again) behaviour, such as the following few lines by Ella Wheeler Wilcox:

‘Laugh and the World laughs with you;

Weep, and you weep alone:

For the sad old Earth must borrow its mirth

But has trouble enough of its own.

Rejoice, and men will seek you;

Grieve, and they turn and go;

They want full measure of all your pleasure

But they do not need your woe.’

Apt thoughts for an unhappy man, although we were not aware of that at the time. Then there were the following prophetic lines, albeit unwittingly so. ‘Prophetic’ because of the number of Mr. Thomas’s pupils who were killed in their early twenties in WW2:

‘Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old Time is still aflying:

And this same flower that smiles today,

Tomorrow will be dying.’

[Digital page 7]

One tradition of the school involved a large holly bush which grew on a grass bank. New boys were initiated by being pushed into the bush. Each September, on the first day of term, the newcomers would line up in the breaks, waiting to get their initiation over with. Those who didn’t, were found and escorted to the holly bush. Boys who cried were mercilessly teased. And I don’t know of one parent who complained that his son had come home scratched and bruised. Had they done so, the boy would have become almost a social outcast at school. The holly bush initiation appeared to be accepted by the masters, some of whom had probably been through it as new boys at the school.

There were, of course, no computers or television sets in those days, so our gang of seven spent our spare time and weekends on inexpensive pursuits such as fishing, shrimping, crabbing, lobstering, swimming, hiking, cycling, camping, cliff-climbing for seagulls eggs, hunting (with one Daisy airgun between us), playing football and other such activities. In the 1930s the beaches and sea around the Gower coast were clean. I also joined the Cubs, Scouts and, later, the Sea Scouts. So far, I think, a fairly normal up-bringing for the post-WW1 ‘Twenties’ and the ‘Thirties’.

But, to get back to the early thirties, we constantly fought with another local gang and made explosions with home-made gunpowder. Even as teenagers we had no difficulty in obtaining the simple ingredients and fortunately never did any real damage. My father kept a cane behind a picture over the dining room fireplace and would have half-killed me if he’d found out. His usual speech when administering punishment was, ‘This will hurt me more than it will hurt you!’ I used to wonder how such a God-fearing Methodist could tell such a lie.

On leaving school at sixteen I wanted to join the Navy but my father wouldn’t allow it so I got a job as a clerk on the Great Western Railway. Then, in 1939, the Government introduced The Compulsory Training Act (conscription) but said that anyone who joined the Territorial Army or one of the other Auxiliary Forces, would be excused call-up. It didn’t take me long to persuade my father that one night a week with the T.A. would be less of an upset to my career on God’s Wonderful Railway than conscription.

So, one evening in May 1939, I joined former school-mates and other friends in the queue to enrol in the local Royal Artillery Regiment of the Territorial Army. One other new recruit was Lance-bombardier Sir Harry Secombe, although he was then plain Gunner Secombe. Even if I say it myself, we looked very smart in our khaki uniform, with neatly-wrapped puttees, polished buttons and cap badge, and silver spurs. The Regiment no longer had horses so the spurs were only ‘dress type’, without wheels.

As a Sea Scout I’d had an ambition to eventually join the volunteer crew of the Mumbles lifeboat but War broke out and, as a Saturday Night Soldier (as the Regulars called the ‘Terriers’), I was mobilised. Fortunately for me I did not become a lifeboatman after demob, because the Mumbles lifeboat was lost with all its crew on 27th April 1947. The ship they’d gone to assist, the Sam Tampa, also went down, with all thirty-nine crew.

[Digital page 8]

We were mobilised on 1st September 1939 and were really looking forward to being sent to France, but as the War raged on, all the 132nd (Welsh) Field Regiment (R.A.)(T.A) [Royal Artillery. Territorial Army.] did was move around the Country from town to town on what was called ‘flying picket’.

That meant we could be rushed anywhere at any time if the Germans invaded. But the nearest we got to the enemy was when they flew overhead on their nightly bombing raids.

One place we visited for a couple of months in 1940 was Macclesfield where I met Edith, my dear wife, who was 18 at the time. But the Regiment was soon transferred to Aldershot and I spent my rare weekend leaves in Macclesfield. I don’t think Edith’s parents quite knew what to make of this strange, foreign Taffy but they didn’t kick me out. With Edith, her parents, two sisters and two young brothers sleeping in a three-bedroom, semi-detached Council house at Brookfield Lane I had to sleep on the rug in front of the fire in the living room, in the company of silver fish which came out of the hearth as soon as the light was switched off. Edith and I spent my longer, seven-days leaves at my home in the Mumbles. We became engaged in January 1942.

Then, in 1942 I volunteered to transfer to the R.A.F. [Royal Air Force] as a wireless operator/air gunner but was asked to consider becoming a trainee glider pilot instead. Although this meant a drop in rank from sergeant to war-substantive bombardier, I accepted.

After six weeks of intensive physical training with Airborne instructors on Salisbury Plain our course ended up at Burnaston Aerodrome. We arrived mid-day Wednesday and in the afternoon were taken up as passengers in Tiger Moths. It seemed that the Army were trying to find out just how quickly they could train glider pilots and we were some of the guinea pigs.

After that we spent all our time in Tiger Moths and link trainers (simulators). Then, nine flying hours later I went solo. But as the nine hours were condensed into only (if I remember correctly) a week I didn’t even manage to get the ‘feel’ of an aeroplane and, when it came time to land during my first solo flight, I nearly headed in the direction of the coast to parachute out. Anyway, I made a successful, if bumpy, landing, bouncing all over the field before coming to rest. Others weren’t so lucky and ended up with their ‘noses’ in the ground, as I did on a subsequent occasion. I also, later, damaged the wing of a Magister training aircraft after making a rather dodgy landing whilst flying solo.

One night I went to see a pal off on a 15-minute, solo, night-flying trip and said I’d have a cup of tea waiting for him in the NAAFI [Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes]. I watched him rise to about 1000 feet then spiral into the ground. He was killed instantly. On a lighter note, the next day another member of the course made a successful landing by flying underneath some telegraph wires – and you can guess how low that was.

The most exciting manoeuvre was ‘spinning’, but at our stage of training this was only allowed when accompanied by an instructor. However, most of us managed at least one solo spin and I know of no-one being carpeted. The problem was plucking up courage to

[Digital page 9]

make it. First you flew to a ‘spin area’ (over open country) and climbed to about 5000 feet. Then you stalled the plane and caused it to spiral earthwards. Meanwhile, you very briefly lost control of your senses. When you regained them you stopped the spin and put the plane into a brief power dive which you hoped to be able to control. Strangely, none of us crashed whilst solo spinning.

For some reason I passed on powered aircraft and was sent to the glider school at Bicester. But I managed to land a Hotspur glider in a hedge. So, as the Glider Pilot Regiment was a part of the Army Air Corps, and not the R.A.F. [Royal Air Force], I was given the choice of either returning to my unit or transferring to another Airborne Regiment. The latter offer was tempting but I had heard that the 132nd Field Regiment was engaged in cliff climbing and other ‘assault’ training in preparation for going overseas. As all my mates were there, I returned to them.

On the 18th October 1942 the 132nd (Welsh) Field Regiment (R.A.) (T.A.) [Royal Artillery. Territorial Army.] sailed from the Clyde on the troopship Marnix, part of a convoy heading for an unknown destination, which turned out to be Douaouda beach, near Algiers. After just over three years we were about to take an active part in the War. More active than any of us expected! However, after three years of intensive training with day and night manoeuvres we were probably one of the best-trained units in any army.

But to continue with the family story. Edith and I have been very fortunate and have been happily married for over half a century. We celebrated our 52nd Wedding Anniversary on the 8th January 1996; have two daughters, Pamela and Angela; two granddaughters, Helen and Pamela; two grandsons, Rene and Raoul, who live in Switzerland and do National Service in the Swiss Army; one great-grand-daughter, Clara and one great-grandson, Aaron.

Let’s now skip the boring boat journey from Scotland to Algeria and join the Regiment after it had invaded North Africa. But first, a brew…

[Digital page 10]

[Page title] Once upon a time

On 24th April 1995 my wife and I called to see Mr.J.L. Gallop, of, Clitheroe, Lancs [Lancashire] when I got the answers to some 52-years old questions although, sadly, he is now a very sick man and house-bound.

Johnny was just 19 years old when he was captured at Tebourba in December 1942 whilst serving in the 2nd Hampshires, and we shared Red Cross parcels in P.G.146, Borgo San Siro. He had the right sort of sense of humour to keep our spirits up and was a good pal – as you are about to find out. One of his skills was knowing just how many times the tea from the Red Cross parcel could be brewed before it was dried in the sun, put back in the 2 oz. packet, and thrown over the wire in exchange for a cob of bread. There were never any complaints and I can imagine what happened if any of the Italian guards brought their wives to England after the war and took them into a cafe for a cuppa:

“Mamma mia, Maria, but this Inglese tea ain’t arfa stronga. Notta bitta lika that meraviglioso tea we used to getta from those prigionieri in Borgo San Siro!”

When we eventually found out that the Allies had landed in Italy Johnny and I planned to escape together. So, in August 1943, I resigned as Camp Leader and we waited for the right conditions, which included an air raid just before the evening ‘count’. Each evening we used to put very rough ‘dummies’ under our blankets but time passed and although air raid sirens sounded in the distance they were never at the right time.

In early September 1943 Johnny started to suffer from appendicitis pains and decided that it would not be wise to attempt the 400 miles (as the crow flies) journey to the Allied lines. I reluctantly agreed with him – I did not relish the thought of performing an appendectomy with some Iti. [Italians] woodsman’s blunt axe on top of one of them thar hills.

On 7th September 1943 the ‘right conditions’ occurred – the overcast sky made it even darker and air raid sirens sounded just before the ‘count’. By this time, Private Vic Clarke of the 1st East Surreys had decided to take Johnny’s place. Because of the air-raid alert the ‘count’ was a hurried affair and took place inside the crowded hut. Thanks to the efforts of the other prisoners, and Johnny in particular, the ‘lumps’ under Vic’s and my blankets were accepted as sick men. Had they not been, there would be no tale to tell.

While this was going on, Vic and I had managed to hide in the shadows outside the hut and we clambered over the barbed-wire without being seen. It wasn’t as simple as that, of course. There were a few dodgy seconds when, despite putting a folded palliase over the top of the fence, my trousers got caught on the barbs, leaving me silhouetted against the sky, which seemed to get lighter. Then, whilst I was lying on the outside of the wire, wondering if I’d broken any bones in the fall, Vic jumped and landed on top of me. But luck was on our side that night and we got away.

[Digital page 11]

I left behind a letter, telling the Camp Commandant that none of the other prisoners had helped me to escape. Vic did not bother to leave one. It was a ‘standing’ letter, with the date (in pencil) being altered daily – except on the crucial day, from 6th to 7th September. Johnny doesn’t know what happened to it.

At the following morning’s ‘count’ (8th September) Johnny gained Vic and me even more time by convincing the guards that we were among the sick who were still under their blankets – there were quite a few of them and the unsuspecting guards fortunately did not make a proper check. So Vic and I were not missed until the evening ‘count’ when, to put it mildly, the Itis. [Italians] were rather displeased.

Johnny regretted not having escaped the previous night especially as Vic and I had apparently got clean away. However, he realised that three of us would definitely have been missed in the ‘count’ and that the trigger-happy guards might even have taken pot-shots at us as we clambered over the barbed-wire.

For those of you who were not in Italy … on the 8th September the Italians signed an Armistice with the Allies, but this was to make no difference to the Italian campaign because the Germans and Fascists continued to fight as before. The effect of the Armistice was to make the guards bewildered and jittery. Would the Germans now withdraw from Italy and let the Allies take over? Would the P.O.Ws now become their gaolers? The prisoners were not told of the Armistice until the following day.

Johnny took advantage of the new situation and, on 9th September, when the chance came, he managed to escape even though the camp was still under guard, albeit a confused one! Because of his appendicitis pains he headed for the Swiss border, which was about 50 miles away, as the crow flies. This compared with about 400 miles to the Allied lines in the South, although both distances could be more than doubled on the ground. He thinks the Germans took over the camp from the Italians the next day.

Johnny reached Switzerland and his appendix was removed during his internment. I wonder how many other P.O.Ws risked going ‘on the run’ with the chance of developing peritonitis at any moment!

Postscript: Tell fibs I do not! Mrs. P.H. Samuelson, of. Bishop’s Stortford, who is writing a book about British P.O.W.s and Civilian Internees, has written to say that she found the following in Red Cross archives:

‘Men developed the tea trading to a fine art. The tea was first used by prisoners, after which the leaves were carefully dried and replaced in the packets. The guards were so fond of this ‘brand’ of tea that, when by chance, a mistake was made and an unopened tea packet was bartered, the guards complained that they wanted their usual ‘proper’ tea.’

So, you may (or may not) be wondering, what happened to Vic and me? Well, we were caught two days later, in the late evening of 9th September 1943 and after a night in Police cells were taken to P.G.27, Cava Manara. We escaped again on the 10th but not

[Digital page 12]

together. Vic escaped with Ernie Johnstone (Coldstream Guards) whilst I was accompanied by Jim Flannery (Green Howards).

Probably because of the Armistice we had not been punished for escaping and were sent out on a work party. At the first opportunity we ran away, hoping that the guards would be too scared to shoot. Jim and I were caught the same evening, having been ‘reported’ by a farmer who had given us civvy clothing and the shelter of his barn. He had then become worried and sent for the guards. Back in Camp we found Vic and Ernie, also in civvies.

The following day Vic and I were interrogated by two unpleasant Jerry civilians who wanted to know the names of any Italians who had helped us during our first escape, but none had. They said that we would be charged with crimes committed in the area during our first escape and ‘made examples of’. We were also told that escaping in civilian clothes was against the Geneva Convention and that we would be transferred to another camp, pending trial. This panicked us into getting away again on the 11th September, with Jim and Ernie, through a hole we’d made in the wire whilst the Italian guards were preoccupied with a Jerry column which had arrived nearby, presumably to take over the camp.

Two weeks later, on 25th September, we found some ‘Reward’ notices (‘Premio’) near the hill village of Bardi and the other three decided to head back towards the Swiss border which was much nearer than the front line, still over 300 miles away as the crow flies. Vic, Jim and Ernie were eventually recaptured and ended up in Stalag 4B – I continued to walk South and crossed the lines a few weeks later, on 29th October 1943.

Jim and Ernie have since died. Vic has emigrated to Oz.

“Jumping Jehoshaphat (Book of Kings)”, you are probably thinking, “Wot an exciting and interesting tale! But wot have I done to deserve a copy?” Well, if you have a copy of ‘A Strange Alliance’ by Roger Absalom, turn to page 238 and you will find a quite complimentary paragraph about me, but I think it makes it appear as though I just walked out of a camp at the Armistice. I have obtained the 1977 letter, referred-to in the foot-note, from Tony Davies and find that my escape is covered in just nine, short, manuscript lines! My name and address are on the letter and I am disappointed that Mr. Absalom did not contact me before telling MY story, so that I could have given him the full and correct facts. However, I realise that he had no special reason to do so for just one person among all the hundreds he mentioned. He lives not far from me and we are on friendly terms.

For example I was a bombardier; my first escape was before the Armistice was heard of; my 48 days walk started at Cava Manara and, most important, I DID keep a daily diary during my escape. Whilst behind enemy lines I did a rather stupid thing for an escaper wearing civvies – I drew rough maps of Jerry gun positions, camouflaged vehicle parks and troop concentrations which I gave to Canadian Intelligence after crossing the lines.

I was then taken to a British artillery observation post and directed fire on various targets, including two hidden Jerry machine gun posts. For these ‘gallant and distinguished services’ I was awarded a measly Mention in Despatches and the Italy Star.

[Digital page 13]

The foregoing ‘escape story’ is, of course, just a very brief summary with many interesting details left out. My full diary is over 70 exciting pages long.

I am hopeful that the paragraph in ‘A Strange Alliance’ will be re-written. Mr. Absalom has written to me, saying,

‘It is true that I omitted to mention your two-day escape prior to the Armistice (and many other statements you made in your letter but that was simply because I regarded them as details not relevant to my purposes in writing the book.’

Also, Olschki, the publishers, have written,

‘I am pleased that you corresponded with Professor Absalom and if and when his book is reprinted he will certainly take care of your amendments.’

Which seems to be fair enough. The author has, incidentally, informed me that he is a ‘Mr.’ and not a ‘Professor’.

[Photograph with caption]

Copy of Reward notice taken off a tree on 25th September 1943 and brought home (the notice, not the tree).

[Original Italian] PREMIO

1800.- Lire it. oppure 20.- Sterline ingl.

a scelta

vengono pagate ad ogni italiano che cattura un

militare inglese o americano sfuggito alla prigionia

di guerra e che lo consegna ad una unita germanica.

IL COMANDANTE MILITARE TEDESCO

[Original translation]

REWARD

1800 Italian Lire or £20 Sterling

You have a choice

will be paid to every Italian who captures an escaped British or American

prisoner of war and hands him over to a German unit.

The German Military Commandant

[Additional caption]

(According to War Office Forms F.4 8 (P.W.) (Italian) 1943, the rate of exchange agreed (through the Geneva Convention) between His Majesty’s Government and the Italian Government was 72 lire to the £ Sterling. So 1800 lire was equal to £25, not £20. (According to Whitaker’s Almanack 1990, £25 in 1943 would have equalled £450 in 1988 value). And, of course, 1800 lire was worth a lot more to the Italian ‘peasant class’ in War-time Italy than its £25 equivalent was to people in the U.K.

[Digital page 14]

[Map with caption]

Route taken whilst escaping through Italy.

Time: 52 days from first escape; 48 days from third escape.

Distance covered: about 400 miles (as the crow flies) which, because of the terrain, was probably nearer 1000 ground miles.

Borgo. S. Siro (P.G.146) First escape on the 7th September 1943.

Garlasco. Recaptured 9th September 1943.

Cava Manara (P.G.27). Second and third escapes on 10th and 11th September 1943.

Broni

Roc di Giorgio

Pianello

Bobbio

Bardi

Bettola

Borgo Val di Taro

Pontremoli

Pievapeligo

Fiumalbo

Pontepetri

Formallo

Vernio

S. Piero a Sieve

Borgo S. Lorenzo

Sanselpocro

Citta di Castello

Umbertide

Montecorona

Caught train for about 70 miles

San Gemini

Cessi

Terni

Poggio Bastone

Rieti

Citta Ducale

Santa Lucia

Borgocollefegato

Capelle

Avezzano

Capistrello

Luco ne Marsi

Collelongo

Villavallelonga

Through the Parco Nazionale d’Abruzzo

Opi

San Donato

Settefratti

Castelnova

Castel S. Vincenzo

Isernia

Sassona

San Angelo

Macciagodena

Crossed to the Canadian lines near Frosolone at about noon on the 29th October 1943.

[Digital page 15]

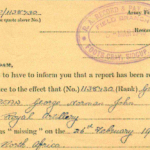

The following is a photocopy of the copy of the letter which Des Jones left behind for the Italian Camp Commandant when he escaped from P.G.146 on the 7th September 1943.

He still has the copy which he carried with him during his escape. This shows that the date is in pencil so that it could be altered each day to save re-writing the letter. But Des omitted to alter the date from 6th to 7th on his copy before going over the wire that evening. He doesn’t remember if he altered the original letter, which was left for the Italian Commandant. Vic Clarke’s name was not mentioned in case he changed his mind about the escape at the last minute.

Des carried his copy with him whilst ‘on the run’ as proof that he was an escaping P.O.W, (in civvies!) and not a spy. Each time he was recaptured (on 9th and 10th September) the Italians let him keep the letter, possibly because of the confusing situation in the first few days of the phoney Armistice.

As far as is known, this is the only record of an escaper leaving a letter behind for his gaolers. Please write to Des if you know differently.

[Letter copy]

To Commandante, P.G.146

Distaccamento XX P.M.3100.

Sir, a few days ago I resigned from the post as Camp Leader for the following reason:- I had decided to escape & wanted to hand the job over properly to another corporal otherwise there might have been confusion. As things are, Cpl. Coates tookover & things are running smoothly for the camp. But the main reason for this note is to clear from suspicion (they are naturally suspected of helping me to escape) all men in the camp. I kept all knowledge of my escape secret & did so without help. When I resigned my post as Camp Leader I gave no reasons – except that I did not want the job anymore.

Sept. 6th

[Signature of Des Jones]

B.D.R. 904661

[Digital page 16]

[Typed letter from Des Jones, found on digital page 15]

To Commandante, P.G.146

Distaccamento XX PM 3100

Sir, a few days ago I resigned from the post as Camp Leader for the following reason:- I had decided to escape and wanted to hand the job over properly to another corporal otherwise there might have been confusion. As things are, Cpl. Coates tookover and things are running smoothly for the camp. But the main reason for this note is to clear from suspicion (they are naturally suspected of helping me to escape) all men in the camp. I kept all knowledge of my escape secret and did so without help. When I resigned my post as Camp Leader I gave no reasons – except that I did not want the job anymore.

D.K. Jones

Bombardier 904661

This is the note I dated 6th Sept. 1942 and left pinned to my mattress. At the time of writing it I did not know that Vic Clarke would be coming with me.

I wonder if the original could be traced in some Iti [Italian] archive? Having spent about 15 holidays in Italy I’d go to see it, next time we visit out daughter and family in Basel.

[Digital page 17]

[Text overwritten] Des Jones. Route & story

[Letter from Des Jones to Keith Killby]

7th March 1991

Dear Keith,

For want of a better phrase, ‘Another Taffy clanger!’. Having read the Monte San Martino Trust literature before, and being up to my neck in ‘enquiries’ at the moment, I only glanced at the papers you sent me – until today. Sorry, mate – I didn’t realise that you were Hon. Sec. [Honorary Secretary] and if I were an R.C. [Roman Catholic] there’d be a few ‘Hail Mary’s’ flying around.

[Marginal text annotation. Illegible]

Thanks for your letter. Like you, I write lengthy letters because I like playing with the word-processor, so I’ll answer your letter in detail. First of all, this is a one-man-band. ‘Club’ is a bit of a misnomer, it is really a welfare organisation – I spend hours each day writing to members who are sick or have other problems. We have a Committee which meets for about 2 hours per annum (incl. drinking time) and then I run the Club for the remaining 364 days 22 hours, which suits me fine. In fact, I have just had a letter from Tom Fairnington who has been organising his Regimental Old Comrades Re-union for 40 years. He says that his Committee of three is very efficient – one on holiday, one sick and himself. The trouble with Committees is that they seem to think it’s their job to find secretaries work – and we have more than enough to do already.

[Text annotation] No

I envy you your photocopier. We have about £700 in the bank and in a building society, but much of it was donated in small amounts by members who have very low incomes – specifically to ‘keep the Club going’, I resist attempts to spend it because one of these days, when I (or my successor) are a bit older we shall need to spend money on stationery, photocopying etc., much of which I scrounge at present. I also claim no telephone or other expenses. Fortunately, at 70-plus I am still able to scrounge, but we shall have to start paying for almost everything in the not too distant future.

[Text annotation. Illegible]

Partisans. Agreed, a very mixed and rare breed which multiplied once the danger had passed. I spent 49 days (after my third escape) walking about 500 (?) miles from near Pavia to Frosolone. The ‘partisans’ were always ‘in the next village’ or ‘over the next hill’. I did find three within a mile of the front line and it was agreed that I would vouch for them (to the Allies) if they’d pinch a Jerry truck and helmet and a British helmet for me. I’d been unable to find a way across the lines and was so desperate that I was going to drive the truck across No-Man’s-Land, changing helmets half way. But I found that the ‘partisans’ were bandits – going out at night to rob their own people. I reported them and their location to our Intelligence (for want of a better word) a couple of days later. As for partisans generally – the Itis. [Italians] didn’t want to know them because they meant ‘reprisals’. In one village near the ‘front’ the Jerries had gone in to commandeer the livestock. With our troops being within gunfire distance one Iti. [Italian] had been stroppy.

When I reached the village he was hanging from an olive tree! In another village, near a burned-out Jerry truck, they’d gone in and driven off with all the young women. So, as you rightly say, the so-called partisans were practically non-existent except as couriers etc. in the North.

Eden Camp – leaflet enclosed. You can immortalise yourself by sending photographs with your name and address. Either mention the Club – or have them displayed in a separate cabinet. The Camp won’t really be finished for another two years or so but it had over 200,000 visitors last year.

Don Jones – his widow still has a few books left. She charges £3 – it puts a price on her husband’s work. She is Mrs. Jones, of Wirrall – I don’t know the post-code. The book is, ‘Escape from Sulmona’, and I did circulate members a year or so ago.

You ask for my story. Well, I don’t usually bore people, but here it is (you can skip through as quickly as you like).

[Digital page 18]

Bombardier, 496 Battery, 132nd (Welsh) Field Regt., R.A., T.A. – Harry Secombe’s old mob. I was blown up and buried at Tebourba, near Tunis, on 4.12.42 when my Battery was surrounded and wiped out after we’d knocked-out eight Jerry tanks. Took part in a rather futile and stupid bayonet charge in an attempt to break through the lines – led by an Officer waving a walking stick. He must have seen a few of those old WW1 movies! Later, still trying to get back to our lines, I ran into a Jerry armoured car patrol hiding in some cactus.

P.G. 98 (Sicily) was escape-proof – and, apart from a shaven head I was groggy. P.G. 66 (Capua) – I was in line to go down a sewer but it was a disaster, long before my turn came. P.G. 59 (Servigliano) – do you remember the Iti. [Italian]Interpreter ‘Domani Dick’, those midnight ‘searches’ and the bed-bugs? Again, I saw no way out.

So, in June 1943 I volunteered to go to a working camp and ended up at Borgo S. Siro, near Garlasco (near Pavia). After a Hampshires lad had died the Camp Leader resigned and I took over. From the first minute I was in lumber with Il Capitano about P.O.Ws working with running sores in the rice-fields and was under constant threat of some sort of punishment. Life was difficult. Also I received a letter from my fiancee saying that she’d been called-up for the A.T.S. [Auxiliary Territorial Service] and didn’t want to go. As it happens, she ended up at their Records Office in Winchester as a civil servant in uniform, but I had visions of her manning anti-aircraft guns and (you know what the rumours were) repulsing beach landings! So I wrote back telling her to expect me home for Christmas ‘to sort the Army out’ and the letter got through. Escaping then changed from a ‘wish’ to an obsession. I even carried the enclosed letter around with me (un-dated).

But the opportunity did not really come until 6th September 1943 (before any mention of an Armistice). Briefly, two of us took advantage of an air-raid alert to go over the wire. My trousers got caught on a barb, and all I could do was laugh – it’s strange how one reacts. We got caught three days later and were taken to another working camp – Cava Minara. The idiots sent us on a working party in the fields – and we made a run for it but were caught later. This time, the Camp Leader and his mate also ran (and were caught). After this second attempt I was interviewed [word inserted] by [text continues] two Jerry civvies (Gestapo ?) who wanted to know if any Itis. [Italians] had helped us during the first escape (none had). I was also told that we would be charged with every crime committed in the area whilst we were loose and then ‘suitably dealt with’. Just words – they were not violent.

That night (11th Sept.) the Camp Leader, L. Cpl. Ernie Johnson (Coldstream Guards), L/Cpl. Jim Flannery (Green Howards), my mate Pte. Vic Clarke (East Surreys) and I got through a hole in the wire just as a Jerry column arrived to take over the camp.

We parted not far from a village called Bardi after seeing the ‘Reward Notice’ With the ‘front’ still about 400 (?) miles away, the other three wanted to go back to Switzerland whilst I wanted to get ‘home for Christmas’. Jim was recaptured and ended up in 8A, but died about seven years ago. I think Ernie and Vic are still missing – I have been unable to trace either.

One reason why they wanted to go back was because we had come across 24 Officers (under Major Clayton, L.R.D.G.) hiding near a village called Bobbio, waiting for a landing at Spezia which never materialised. Major Clayton died a few years ago but his son is still a serving Officer (or was).

I made a bee-line for the ‘front’ and eventually crossed the line at noon on 29th October 1943 by running down a hill [text annotated] during/after our attack [Illegible word. Text continues] near Frosolone, through a Company of Jerries and across No-Man’s-Land. Like a right twit I was in the usual ‘civvies’ and carried rough maps which I’d (drawn of Jerry postions, camouflaged car-parks etc. A Canadian patrol took me to an Artillery O.P. where I directed

[Digital page 19]

[Annotations are marked across the page, mostly illegible]

fire on two Jerry machine guns (which I’d passed} near the village of Macchigodena and explained my maps. This resulted in a measly Mention in Despatches and the Italy Star.

I arrived home on 4th December 1943, in time for Christmas! My fiancee and I got married and the real War commenced, Army v Jones. I offered to be ‘dropped’ into Italy and blow up any bridge the Army cared to mention, then make my own way back, in exchange for my wife’s discharge from the Forces, even though she did have a cushy job. It’s strange, but once I arrived home I really wanted to go back and do it all over again. Anyway, the ‘deal’ fizzled out, but I kept on, and on, and on, and on etc. and, believe it or not, my wife was discharged in April 1944!

So, that’s my boring story, which is in well-typed diary form but no-one wants to publish. It is at present with a publisher, together with two novels (non-War) and I am awaiting my 200th rejection slip. There’s no way I’ll pay a vanity publisher.

By the way, I’ve written this letter without reference to the diary, of course, so there may be the odd small discrepancy.

One of our members, Harry Esders, has just been awarded the Polish Gold Cross of Merit with Swords, The Home Amy Medal and The Cross of Valour.

And today I have received two more applications for membership – from Rodney Hill, Reigate and N. Prior, Southend-on-Sea. Also a couple more enquiries from people asking what we are about – as the result of the newspaper messages to the Gulf.

Accounts. The very detailed ‘books’ are kept by my wife, supervised by a stingy I, mean former Vatman – me. Every single letter is listed in the post-book. The accounts are audited annually – normally by a Royal British Legion treasurer.

I can’t help wondering what happened to all those ‘help’ letters I gave to various Itis. [Italians] I was so obsessed with getting home that I never stepped anywhere except for a few hours’ kip. Attached is the usual type of newspaper story, but the truth is that the two (young) ladies just gave my three friends and me a bite to eat and warned us that the local Fascist boss lived in the in the next farm. It was barely a half-hour stop! Anyway, I’ve been to see them in Merthyr Tydfil and (through my M.P.) arranged for them to be ‘honoured’ by Linda Chalker.

If you ever feel that you’d like a change from Trust work – don’t forget to consider being Hon. Sec. [Honorary Secretary] of this mob. I have several ‘projects’ (un-connected with the War) which I would like to get going for the benefit of man(and woman)kind but they would take all my time and energy.

Meanwhile, the North East lot (about twenty of them, with a local Lt. Col. as President) want to host this year’s A.G.M. up there in Geordieland. I’m not keen, because many (maybe most) of our members can’t afford a night’s B.& B. But it is only fair to let them ask members for their reaction. I favour Leeds or Brum (as in previous years). Then there is the Whitehall Armistice Parade. Ten attended last November and we are expecting twenty this year. Last November one chap collapsed (history of heart attacks). When he came-round he found Claude struggling to get his false teeth out. Except that he hasn’t got false teeth.

If you have any info, about my ‘help’ letters, or that ‘Order to Stay-put at the Armistice’ (which resulted in thousands being shipped off to Stalags) I’d be pleased to know.

[Digital page 20]

[Page title] Places passed en route to Christmas dinner

6th September 1943 to 29th October 1943

Borgo S. Siro [Annotated text] Out 6.4.43

Garlasco

Mortara [Annotated text] Caught 9.9.43

Cava Manara [Annotated text] Out 10.9.43 Caught / Out 11.9.43

Pavia

Broni

Roc di Giorgio

Pianello

Bobbio

Bardi

Bettola

Borgo Val di Taro

Pontremoli

Pievapeligo

Fiumalbo

Pontepetri

Formallo

Vernio

S. Pierre a Sieve

Borgo S. Lorenzo

Sanselpocro

Citta di Castello

Umbertide

[Annotated text] I think they’re in order (Diary away at the moment) [Text continues]

train to

S. Gemeni

Cessi

Terni

Poggio Bastone

Rieti

Citta Ducale

Santa Lucia

Borgocollfegato

Capelle

Avezzano

Capistrello

Luco ne Marsi

Collelongo

Villavallelongo

through Parco N. d’Abbruzzo

Opi San Donato Settefratti

Castelnovo

Castel S. Vincenzo

Isernia

Sassona

S. Angelo

Macchiagoden

[Digital page 21]

[Map] PRISONER OF WAR CAMPS

PUBLISHED BY THE RED CROSS & ST. JOHN WAR ORGANISATION

[Index] to Camps

[Indexes continue down the right side of page]

[Annotated red line drawn over map to indicate route taken, with the marginal comment in red ink, ‘very roughly!’]