Summary of Richard H. Rev Capt Hill

Captain Rev. Richard H. Hill was a Padre in the Royal Army Service Corps attached to 72nd Field Regiment, R.A. He was captured in Libya on 1st June 1942 and transferred to Italy, where he was imprisoned first at PG41 Montalbo and then at PG49 Fontanellato.

After the mass escape from Fontanellato in September 1943, he set off south to rejoin the Allies but was recaptured on or around 8th October. He was sent to Germany.

While on the run and when in Germany he kept with him two paintings made at Fontanellato by fellow prisoners Captain W. Glover and Lt. P. B. Swain, eventually taking them back to England. The following extract is taken from Rev. Hill’s Reminiscences. He died in April 2000.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital Page 1]

[Handwritten note] Reminiscences of Capt Rev. Richard H. Hill, Padre in RASC attached to 72nd Field Regiment, RA, British 8th Army

[Chapter number] Chapter IX

[Chapter title] The Libyan Desert. February 22nd – June 1st 1942

Our convoys now started rolling south again, through Damascus, down the whole length of Palestine – from Dan to Beersheba, in the familiar Biblical phrase – across the Sinai Desert and the Suez Canal until we arrived back in Egypt, whence we had started seven months ago, though it seemed more like seven-years.

We paused for a few days at Ismailia and, as it was considered that there would be little call for band concerts in the desert, the colonel instructed me to take the bandmaster, a driver and a lorry and to transport all the band instruments to Cairo, there to deliver them for safe keeping to the office of Messrs: Thomas Cook & Son. Although I think he accepted the inevitability of such a step, the bandmaster, who was a professional violinist called Cohen and not an enthusiastic soldier, was very grieved and there was much wailing and gnashing of teeth which I had to calm as best I could. Somehow or other we located Thos. Cook and duly deposited the instruments, which I hope someone remembered to collect after the war.

We arrived in the area of Acroma in the Western Desert on 22nd February 1942 and began to adjust ourselves to a life which was very different both in physical surroundings and psychological atmosphere from what we had known before. For the last seven months we had been nowhere near the enemy and

[handwritten footnote] Provided by his son, Steve Hill to Monte San Martino Trust as archive material 16 November 2015

[Digital Page 2]

might have been on extended T.A. exercises. Now we were obviously in a battle area and it was strange to think that, a few miles west of us across the desert, there were real live German and Italian soldiers living under just the same conditions and with just the same hopes, fears and grumbles that we had. In spite of that, the occasional contacts which our division made with them were most unfriendly.

We lived in tents, dug into the ground as in Iraq, except where the ground was too rocky for any real digging, and the chief discomforts were caused by the severely limited supply of water and by the periodical sand storms. In one letter home I wrote: “The sand storms seem to come every other day and at ti1lles visibility is reduced to only a few yards. The sand covers everything and in a very few minutes ones bed and kit are covered with a thick coating of dust and it absolutely fills ones ears, nose and mouth. Our eyes are protected to some extent by goggles of various sorts but nothing is really dust proof. The cooks have the worst time, as the wind blows their tarpaulin sheets about and the sand drifts over all their pots and pans and of course into the food itself, which scrunches as a result when you eat it. One lot of porridge proved altogether uneatable, as the percentage of sand was really too much!” The lack of water made washing and laundry difficult and my need for handkerchiefs was not reduced by the desert atmosphere quite as much as I had hoped it might be, but my devoted batman, one Clarrie Hudson, was indefatigable in finding ways and means of keeping me supplied with clean things.

He looked exactly like the drawings one sees of a cave man and he was not very good on his feet and subject to lumbago, so I think

[Digital Page 3]

he was considered admirably suited to attendance on the padre. I could not have wished for a better friend and assistant in all the circumstances and I think our long partnership suited him too. He had been a Territorial of long service and was then just forty, he looked much older.

Services often had to be held in man-made “holes of the rocks” and “caves of the earth” but sometimes open air services were still possible. Congregations however were always small, partly owing to the obvious practical difficulties, but also to the strong antipathy to public worship which seems to possess most Englishmen, whatever their circumstances. In one letter I refer to my long round of Easter services: “… they have met with rather varied success. My first effort at A Company (the former Supply Column) was rather disastrous, though not without humour. I had arranged a service at 8.00 p.m., as people are only available in the evening and I had dinner in the mess beforehand. The service was to be in the open, outside the mess, and when we emerged at 7.50 p.m., needless to say there was not a soul in sight. At about 8.05, two zealous souls arrived, but by that time the whole thing had become the subject of enormous mirth and nothing could be done. Messengers were dispatched into the gathering darkness in all directions to impress a congregation, while a running commentary of witticisms was kept up among the assembled officers. Of course it got much too late and dark to do anything, so the party finally broke up amid great hilarity, though not unmixed with quite genuine apologies. So I fixed another evening and on that occasion underground forces had been at work, as we collected about 60 men and all the officers – even

[Digital Page 4]

the avowedly “pagan” ones – put in an appearance”.

One of my non-ecclesiastical activities was to teach people to identify the major stars and constellations, as these were used, at least in theory, for desert navigation, though I suspect that not many navigators acquired enough skill to obtain very much help from them. However it was always enjoyable to stand with a small group in the darkness, all staring into the sky till our necks ached and to try to ensure that we really were all looking at the same star. It came as news to some people that the stars had names at all.

At frequent intervals our division sent out highly mobile columns consisting of 25 pounder field guns, anti-tank guns, lorry borne infantry and supporting units to obtain information and to do such harm as they could to the enemy. Their tactics were hit and run and their purpose was to find an advanced enemy post, fuel or ammunition dump, hit it as hard as possible and make a quick get away. This required both courage and military expertise, not

least in navigation by map, compass and stars, as to get lost or to run into a minefield would mean disaster.

When these operations were afoot, I was sometimes posted temporarily to the Field Ambulance, with whom I had stayed occasionally in Cyprus, so that I could do something to provide a ministry to the wounded who might be brought in. Fortunately, I do not remember that we ever had large numbers while I was there, but there were of course always some, including on at least one occasion some Germans, who seemed much relieved and pleased to find themselves receiving just the same care as our own men. I always found these short tours of Duty at the Field

[Digital Page 5]

Ambulance a strain, as I had had very little experience of hospital, work at all and certainly no training whatever for this very specialised and demanding part of it, so I felt that my efforts were very inadequate. Sadly, there were always some·funerals to take and letters to write to next of kin.

I had now been with the divisional R.A.S.C, for two years and I had several times talked to the senior chaplain about the probability that a move would be good both for them and for me. Until then nothing had come of it, but there was now a vacancy for a chaplain with the 72nd Field Regiment R.A. in the 150th Brigade and it was decided that I should be posted to them. It seems disgustingly smug to say so, but I thought that our colonel would be opposed to my going, so I asked the senior chaplain of the division to see him personally and to explain the situation tactfully. Unfortunately, he failed to do so and merely sent the colonel a formal message to say that with effect· from 1st May I was to be posted to the gunners. As I feared, the colonel was very angry and rang up the staff chaplain to protest, taking it for granted that I too was opposed to the move, so I found myself landed in just the situation which I had hoped to avoid.

Fortunately, the staff chaplain, though rather shaken by the colonel’s onslaught, handled the situation quite well, so when I hastened to see the colonel myself, I found him already half reconciled to my departure. When he discovered that I thought the move desirable, he accepted the idea with quite good grace, though I think he found it difficult to understand my motives. I was of course very sorry on purely personal grounds to leave many good friends in the R.A.S.C. and not least my faithful old

[Digital Page 6]

guide, philosopher and friend Clarrie Hudson, but I did my best to ensure that his new “situation” was one in which he would find “a good home”,

[Digital page 7]

[Chapter heading] Chapter X

[Chapter title] THE.BATTLE.

On 1st May 1942 I duly reported to the H.Q, of the 72nd Field Regiment R.A. where I was very kindly welcomed, especially by the adjutant, Geoffrey Phalp, who later became Peter’s godfather, and by Major Leslie Richmond, the very senior and much respected regimental medical officer. Like the other units in the division, the 72nd was a Territorial regiment and most of the officers and men were old friends in civilian life back in Newcastle-on-Tyne,

so in spite of the goodwill, I was inevitably the odd man out at first,

A three-day sandstorm somewhat inhibited efforts to prepare my personal dug-out and I record in my first letter home: “I lived in a little shelter tent about 6ft x 3ft x 2½ft high at the apex so it was not too spacious. My kit had to stay outside and I had to dress and undress and wash either outside in a very cold wind or lying prostrate inside. However by various contortions and acrobatics I managed to exist all right. Now I have moved into a dug-out about 6ft long by 4ft wide by 4ft high which is pretty small but much better. There is no room for my camp bed so I just use my Li-Lo mattress which lies on a shelf of earth occupying nearly half the space. Beside it is a narrow trench in which I can stand – although of course not nearly upright”.

Major Richmond was very kind in taking me round the batteries to introduce me to people and in helping me to arrange

[Digital Page 8]

services for them but, as in France two years before, I had arrived at a new unit on the eve of a crisis with no time to get to know people or to learn the new ropes.

The history of the desert war almost suggested that each side took it in turns to chase the other across the desert and now it was. the Germans’ turn to attack. In anticipation of this General Auchinleck, -the Commander-in-Chief, Middle East and General Ritchie, the 8th Army Commander, had prepared a line of defended areas, known as boxes, which ran from Gazala, on the coast, 45 miles due south into the desert to a spot called Bir Hacheim. Each box was defended respectively by brigades of the 1st South African Division, of the 50th Division and by a brigade of the Free French, who were at the southern end of the line at Bir Hacheim.

On the night of 26th May, General Rommel, who was almost as much of a hero to us as to his own men, began his expected attack by sending three of his divisions – the 15th and 21st Panzer and the 90th Light – round the end of our line at Bir Hacheim with the object of coming up behind us and driving straight on to capture Tobruk within a few days. Behind our line he was confronted by the British 1st and 7th Armoured Divisions and the Guards Brigade and there was heavy fighting, which held up the German advance and upset their timetable. The Germans also suffered from the opposition provided from the boxes and decided that they could not afford to keep making the detour round Bir Hacheim but that they must punch a hole through the Gazala line. They cleared a passage through the minefield and opened a corridor on each side of our 150 Brigade box, so we

[Digital Page 9]

were completed surrounded. However as they still had to run the gauntlet of attack from our box, they decided that 150 Brigade must be eliminated and the direct attack on our positions began on 29th or 30th May.

All this information was no doubt well known to those who were directing our battle, but it was by no means clear to me and I only knew that shells were flying about in both directions in ever increasing profusion. One large one landed not very far from where I was, on one occasion, but, no doubt fortunately, it failed to explode and the effect was most curious. It was not of course visible in flight, so it seemed suddenly to leap from the ground and then it proceeded in a series of diminishing bounds until it came to rest.

My memory of these few hectic days is blurred and I have few clear recollections of particular episodes. After the first day or so, our H.Q. moved a little way and we lived, to use rabbit terminology, in scrapes rather than in burrows. Meals were in frequent and generally consisted of bully beef and biscuits, which are not an ideal menu when the weather is hot and water scarce. The first casualty that I remember was one of our officers, who was brought back by his driver from an observation post mortally wounded and soon afterwards I took a hurried funeral service for a gunner who had been killed. We buried him just as he was, without even a blanket shroud, in a shallow grave. I remember spending time in the gun pits of a troop very near H.Q, and also with the wounded who had been collected in some slit trenches, but I cannot be sure whether that was our Regimental Aid Post or whether I was with the doctor. As in France two years previously, I felt I was

[Digital Page 10]

making no useful contribution to the proceedings and this was again at least partly due to my having s very recently come to the regiment and partly to my continuing and regrettable ignorance about where and how a chaplain should operate during a battle.

Later on, as a pastime and mental exercise, as one might do crossword puzzles, I wrote some verses and one so-called poem is about the battle. The lines are entirely contrived and without artistic merit, but a few of them may be just worth quoting as giving some impression of the scene. The pronoun in the first line refers to the shells:

“They fall and burst with well nigh deafening- crack

And stones, steel splinters, earth all heavenward fly

While upward rears a column of dense smoke,

As if a small volcano had sprung up

And Earth were adding her fierce wrath to Man’s.

The stones and splinters patter down to earth

While slowly drifts the pall of acrid smoke.

And all the time the answering guns speak out

With tongues of flashing flame that shame the sun;

The piece recoils, the earth shakes with the bang

And, whiffling through the air, the shell departs

Its grim and fatal mission to perform,

The sweating gunners speedily re-load,

Awaiting orders from the officer

Who stands at the command post and relays

The range and elevation and all else

The gunners need to know in bawling tones

Which wear his voice away and parch his throat.

So ceaselessly they toil in dust and heat,

Half blinded by the salty sweat that runs

In rivulets from brow and every limb

Until each body’s coated with thin mud

Compounded out of sweat and desert sand.

So feverish activity prevails

[Digital Page 11]

In every. gun-pit; but not far away

A sad and silent contrast is revealed

Where lie the wounded, comfortlessly laid

In dug-outs and slit trenches, propped with coats

And blankets, but with small relief from pain

And meagre sips of water, mocking thirst.

Cascades of tiny gravel tumble down

The steep sides of the trench, while overhead

The blazing sun stares down, as motionless

As o’er the battlefield of Ajalon.

And so the lagging, languid hours crawl,

Filled with ceaseless noise, smoke, dust and heat,

Until at last the watching sun declines

And stones and little tufts of thorny scrub

Begin to point long shadows to the east.

The deep blue heaven turns to green and gold,

As if the sun’s gigantic searchlight played

His slanting beams across the rainbow’s web

And swept the furthest corner of the sky,

Then, slowly dying, let the colours fade

While, soft and silent, gently there descends

The deep, blue, velvet curtain of the night.

And as it falls, the noise of battle dies,

As if another tragic act were played

Upon the desert stage where, all too real,

The desperate action is to be performed.

So nightfall brings a temporary respite

And weary actors fall in brief repose

While others .in their turn, keep ceaseless watch

And shadowy patrols steal back and forth.

So still, so silent sleeps the desert now

That one might almost think that none survived

The desperate battle of the daylight hours.”

As the German tanks closed .in on the gun positions, the 25 pounder field guns were often fired directly at them, at very close range, which must have been an appalling experience for the

[Digital page 12]

tank crews, just as the gunners were exposed to the close range fire of the tanks.

By 1st June the brigade could do no more. There had been many casualties, including the brigadier himself, but the decisive factor was that there was no more ammunition.

I do not remember how the order was given, but I somehow became aware that we were to leave our position and that each man was to do his best to make his way north into the box on that side of us, which was still a going concern, not having suffered the same kind of assault. So, for the second time in my distinguished military career, I abandoned all my kit, including this time, I regret to say, my Field Communion set with my few books in it. I do not know why I did not try to take it with me but, incredible as it seems, I did not lose it, for months later it arrived at Marsh Brook, still bearing a label marked with the words in German – “unknown chaplain”. Some German soldier, going over the battlefield, must have picked it up and handed it in to his unit. (If he also found the silver bracelets I had bought for Suzanne and Julian in Iraq, he did not hand them in too, but perhaps they were his reward for rescuing the Communion set.) The German authorities in due course passed the set on to the Red Cross, who returned it to the Chaplains’ Department and, as my name was in the books it contained, I was identified as the chaplain to whom it had been issued and it was sent to my home address. After the war I had the opportunity to buy it and I used it regularly for house Communions in the parishes.

However, on 1st June 1942, I regrettably and regretfully abandoned it and, like Abraham, went out into the desert, knowing

[Digital page 13]

not whither I went. There was a number of our men wandering over a large area in ones and twos and I spoke to some when we came in hail of each other, but none of us had any helpful information to impart and everything seemed entirely vague. I wondered uneasily whether we might arrive in a mine field, but this fear was dispelled by the appearance of a long straggling line of Italian infantrymen who came over a ridge in front of us. They fortunately did not consider us to be suitable targets and they made vehement gestures for us to come over to where they were. In the circumstances, we had little option but to accept their not very kind invitation. We were “in the bag”.

[Digital page 14]

[Chapter heading] Chapter XI

[Chapter title] PRIGONIERO DI GUERRA

[Chapter sub-title] JUNE 1ST 1942 – SEPTEMBER 9TH 1943

The diminutive Italian soldier, with whom I eventually came face to face, had a lugubrious expression and he may well have thought that I was not a very rich prize to have capture., He pointed to my watch and I thought at first that he was going to claim it as his personal booty, but it appeared that he only wanted to know the time, so my first encounter with the enemy was not exactly dramatic.

I cannot remember the exact sequence of events, but that evening I found myself sitting on the ground with a large number of fellow prisoners at some Italian headquarters, surrounded by a ring of guards, while a ceaseless stream of German vehicles flowed past us, carrying supplies and reinforcements up to the front. They were not a cheering sight for us.

During the evening, I was escorted to a tent where an Italian officer made a rather half-hearted attempt to interrogate me in French. I tried to assure him that I had no intention of discussing military matters, but I think he probably concluded that my information on the subject was even more limited than my knowledge of French and that I was in any case unlikely to help him with his enquiries, so I was soon removed from his presence.

For the next ten days or so we were in the position of

[Digital page 15]

livestock being carted from one market to another. We were loaded into lorries, driven down the line of communication, unloaded, confined for varying lengths of time in a pen and loaded up again for a repetition of the process. The lorry journeys were not exactly comfortable, but no doubt much preferable to the long marches which were often the lot of prisoners. In this way we arrived successively at Derna, Barce and finally Benghazi, whence we were flown across the Mediterranean to Lecce, in Southern Italy, where we were incarcerated for that night in a former tobacco factory. From there we were taken on to a large transit camp at Bari where we remained for three weeks with very little food, as the invaluable Red Cross parcels were not available there. I discovered that if one ate one tomato and a very small piece of cheese as slowly as possible, it was also just possible to imagine that one had had a meal. Bread was always going to arrive tomorrow or the next day, so the favourite catch phrase became “piccolo pane dopo domani”, which was alleged to mean “a small loaf after tomorrow”.

In spite of our lamented absence, the war in the desert was continuing and, contrary to hope and expectation, Tobruk fell to the German attack and many prisoners were taken there. The Italians were of course jubilant and hastened to supply us with newspapers containing triumphant accounts of the victory. As we knew later, the unexpected fall of Tobruk did cause something of a row at home but, to the chagrin of our captors, the huge headline in their newspaper “Pandemonio a Londra” was greeted by us with unrestrained mirth.

After three weeks, a large party of us was transferred to our first permanent officers’ camp which proved to be at

[Digital page 16]

Montalbo, a beautiful spot in the foothills of the Apennines, south of Piacenza. The journey was made by train and in passenger carriages, which we later looked back on as great luxury.

We were greeted at the camp, which was located in an old castle, built round an open courtyard, by the Senior British Officer, who explained to us how the camp was organised and what would be expected of us. We were under his command and all dealings with the Italian authorities were in his hands, but the inmates of the camp regulated their day to day life themselves.

This regime worked very well and, as everyone now knows, officers’ camps came to resemble universities in their wealth of educational and artistic activities, made possible through the channel of the Red Cross. Montalbo was a small camp, but all such activities flourished and we had an excellent home made pantomime at Christmas, besides a lot of other music making. A notable event at Christmas 1942 was a visit to the camp by a deputation of ecclesiastics, who brought greetings and small gifts from the Pope. I think this gesture by Il Papa made a considerable impression and it was a witness of the fact that there are values in life which war cannot destroy.

There was another chaplain in the camp, an Englishman who had settled in New Zealand and had come over with the forces from there, so we shared the “parochial” ministry. In the excellent Red Cross library there was even a copy of the S.P.C.K. Bible commentary, so with its help I prepared a course of lectures on the Bible which was suffered with great patience and endurance by a faithful few.

Of course there was continuous cold war with the Italians

[Digital page 17]

and generally there was one of our number in the “cooler” – the solitary confinement cell – after some small skirmish with them. Roll call parades were held twice a day and guards would patrol the dormitories at night, shining torches on to beds to determine whether a sausage shaped mound was indeed a human frame or some foreign body designed to resemble one. There were frequent searches of the whole building to check on any cloak and dagger work which might be in progress and at such times we were of course ejected and had to wait about for hours in the compound, like hens, the trap door of whose house has been shut.

It was remarkable how well men of very different temperaments managed to adjust themselves to captivity and I do not remember any serious cases of psychological trouble. I always felt particularly sorry for the regular officers whose careers had been so decisively checked and who must often have felt frustrated and humiliated, however brave a face they put on their circumstances.

From July 1942 until March.1943 we continued our placid existence at Montalbo until it was disrupted by our being moved en bloc to another camp.

The details of the journey escape me, but I think it must have been by train and I do remember our marching out of the castle late one evening, our column thickly hemmed round by guards many of whom carried flaming torches, which rather suggested that we were all taking part in the making of some film. During the march (which I suppose must have been to a railway station) I found myself next to one of our intellectuals, who expounded to me the ontological argument for the existence of

[Digital page 18]

God, about which he knew far more than I did, but what prompted this .subject in such unlikely circumstances I cannot imagine.

Our new quarters were in the village of Fontanellato, in the plain of Lombardy not very far from Parma. The building was brand new, built as an orphanage but never so far occupied, and another officers’ camp and our own were combined in it. It had three storeys with a large assembly hall, a dining room, large airy dormitories and good washrooms and kitchens We had proper beds and bedding and .our laundry was done at a neighbouring convent. There was quite a liberal·supply of macaroni in various forms and of vegetables so, with our Red Cross parcels, we were very adequately nourished. Mail from home came through very well.

With more space and more people our camp activities soon got under way and classes and lectures on all kinds of subjects were in full swing. One course that I enjoyed was on early Greek philosophy and Plato, given by a considerable scholar who was alleged to have joined the Indian army in order that he might have time to read and write philosophy. There were excellent productions of many plays including, I remember; “Lady Windermere’s Fan” and “Blythe Spirit” and a Choral Society flourished. One of my very good friends was Harry Spence, with whom I have happily kept in touch, and when we meet we always sing together the top and bottom lines of “Gold und Silber”, as arranged by our .music maestro, Pat Gibson,

Through the good offices of the convent we were able to buy a very nice paten and chalice and we could always get wafers and wine, so I was able to set out the hall for our Communion services on Sunday as adequately as one might prepare the service

[Digital page 19]

in a church hall at home.

We had a large wire-fenced compound on one side of the building which became a football ground, though of course the ground was quite bare and baked as hard as concrete. A large number of teams (seven a side or thereabouts) were formed, often boasting most colourful titles, and the league competition provided constant excitement. The blazing sun and extreme heat never diminished the energy of the players.

One brief episode caused me some distress, though it had nothing to do with us. Outside the compound there was a number of young geese, whom we had watched growing up and who would parade up and down outside our wire pen as if fully aware that we were the prisoners. One day the Italian sentries who were not on duty seized the unfortunate geese and ruthlessly plucked all the feathers from their breasts and backs, leaving them so sore and shocked that they had to let their wings trail helplessly on the ground and they were only just able to stand or walk. They were a pathetic sight and it took them a long time to recover. I regard our now popular duvets with some suspicion.

When.one thinks of the horrors endured by prisoners in the hands of the Japanese and of the hardships and dangers of men on the fighting fronts and of people under bombing attacks at home, it seems extraordinary and shaming that we should have been physically so well off. The strain was psychological, due to the isolation and the uncertainty of our situation. We were con strained to dwell with Mesech and to have our habitation among the tents of Kedah which, however comfortable, were still hostile and it was disconcerting to realise that we·were in the hands of

[Digital page 20]

people to whom our welfare was of no real concern. The long separation from home inevitably imposed strains too heavy for some families to bear and the impossibility of having accurate news about the progress of the war was extremely frustrating. There was always great excitement over new prisoners and the news they could bring and I remember the amazement with which we listened to a lecture on the battle of Alamein and heard about the immense forces under the command of General Montgomery, so utterly different from anything we had known.

Then there was the total uncertainty about how long our captivity would last. We never doubted for a moment that the allies would be victorious, but when? And should we get safely “out of the bag” when the time came? When two friends decided to take a few turns together round the compound, the conversation always started with the forlorn question “Well how long do you give it now?” and then would follow the rambling speculations which had already been rehearsed a thousand times.

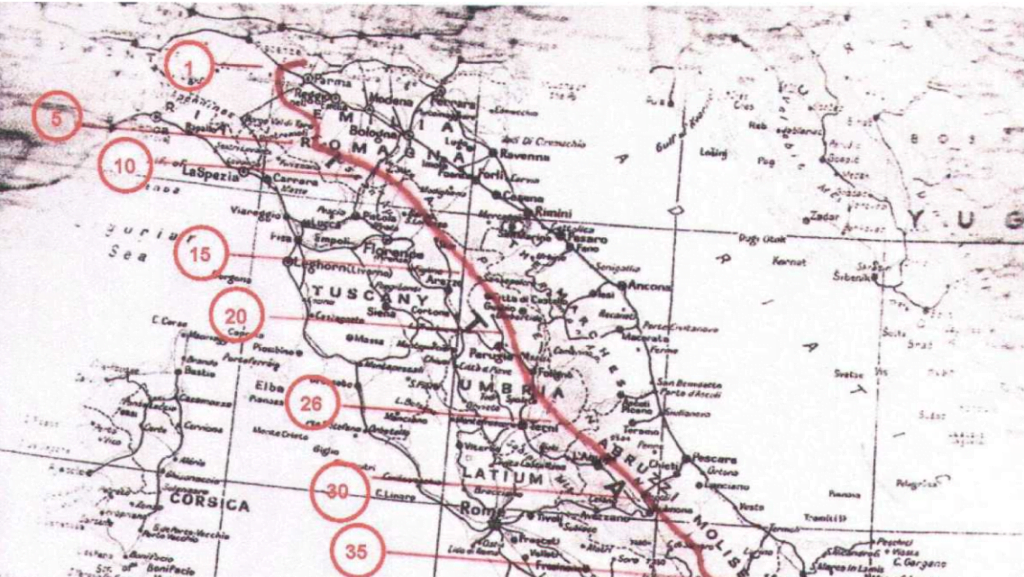

However during the summer of 1943 we did become aware that Italy’s ability to continue the war was being steadily eroded. I rather think that our Senior British Officer and his immediate staff were occasionally receiving information from home by underground means, but anyway he organised us in small parties, who would go together if opportunities of escape on a large scale ever offered. We all prepared some means of carrying essential items of kit and particular possessions. Among my own, I included two pictures which I had commissioned from two of our many excellent artists: a view of Fontanellato from the top windows of our building by Paul O’Brien-Swayne and an impression

[Digital page 21]

of the surrounding countryside with its poplars and vines by Bill Glover. I wrapped the pictures round a birch stick which I chose from the fuel store and folded round them a strip of old blanket and by this means I managed to carry them with me for the next nineteen months and they have hung in their frames on our walls at Berrington, Bromyard, Ledbury and Ludlow.

The party of which I was a member consisted of two besides myself – a Presbyterian minister from the Isle of Islay and an Engineer officer called Roques who had been in the Army

Post Office and was therefore always known as Posty. The minister’s name was Hector Macdonald and he was a typical Scot, decidedly dour in manner and appearance, a man of few words but of dogged determination. Posty, on the other hand, was a cheerful soul, always genial and optimistic, rather short and round, whereas Mac was tall. and seemed to lean to one side, with his arms dangling as if partially out of control.

Suddenly the tremendous news came through. Italy had surrendered, Mussolini had fled and the obvious head line was placarded across th ·camp notice board by our jubilant journalist – “BENITO FINITO”!

But what was to happen now? Should we be released at once? Were the Germans continuing the war in Italy? Would they take over the camp? Could we escape? We were not left long in doubt for the S.B.O, announced that the Camp Commandant, who had always been very much “an officer and a gentleman”, had told him that he did not propose to obey his orders to hand us over to a German guard. He had withdrawn his Italian guards and we should find a hole in the perimeter wire fence. It was a dramatic and

[Digital page 22]

chivalrous decision on his part and one fears that he may have suffered for it”

It did not take us long to pick up our waiting packs and to find the hole in the fence, through which we joyfully trooped.

[Digital page 23]

[Chapter heading] Chapter·XII

[Chapter title] NO FIXED ABODE

Some good staff work must have been done beforehand somehow by someone for, when we all arrived in a small wood, local inhabitants appeared from all sides, bearing quantities of civilian clothing. It soon looked as if a huge al fresco jumble sale was in progress and I was able to select a jacket, shirt, pair of trousers and belt, all of a suitably rustic appearance, though for practical reasons we kept our army boots, in spite of the fact that they considerably sabotaged the completeness of our disguise. Our uniforms were dumped in the wood.

Most of us slept under the trees and in the morning we sallied forth in our small parties in our new role as honorary members of the Italian peasantry.

Most of us had very little information indeed about the situation in the country, except that the fighting front was some where in the south and was supposedly advancing and that the country was full of German troops who might or might not be withdrawing.

We knew much later that some of our own parties had successfully made for Switzerland and that a very few had made their way some two hundred and fifty miles south, passed success fully through the German lines and rejoined our own forces. Among these heroic few were Geoffrey Phalp and his companion Gervase Nicholls, also of the 72nd Field Regiment R,A, It was really a

[Digital page 24]

great achievement.

Posty, Mac and I had no idea what to do except to begin a vague walking tour in a southerly direction. A few people suggested trying to go to ground somewhere and just wait for our troops to arrive, but this seemed altogether too forlorn a hope, so we set out. At first we went very cautiously across country, avoiding roads and villages·but we realised that·we should have to pocket our pride and beg·our bread and this would involve the risk of going to farm houses.· We soon found that we could expect a friendly welcome. Everyone recognised us for who we were, in spite of our impenetrable disguise, although we were once thought at first to be German spies. The farms were most generous in giving us food which we took away like tramps, which is exactly, what we were. At night we slept in the open, in any suitable-spot we came to.

For some reason we did stay for a few days at one farm, hiding among the reeds· on a canal bank during the day and sleeping in a hay loft at night, when the air was filled with the ceaseless whirring song of the cicadas, However we soon wearied of this existence and pressed on.

Before long our progress was halted by a river, which I. think was the Taro, and we decided that we should have to cross it by a road bridge which we could see. We walked along beside the river and climbed up the embankment onto the road, when we saw, to

our dismay, a German sentry on the bridge, not many yards away. Surprisingly, he did not challenge us and, remembering just in time that we were only honest Italian peasants homeward·plodding our weary way, we trudged past him, carefully avoiding his eye. He

[Digital page 25]

must, like us, have wanted a quiet life, but perhaps he permitted himself a lazy grin as we shambled past in our stout British army boots.

One morning we must have been hungry earlier than usual because we approached a farm where threshing was. going on in the yard behind the house. As we came nearer to the house, we were astonished and moved to hear the voices of the B.B.C. singers singing the hymn “Eternal Ruler of the ceaseless round”. This sudden and almost unbelievable reminder of home and its familiar routine was quite overwhelming. Unfortunately I cannot remember anything about our interview with the people at the house.

In due course we found that we had successfully taken to the hills and were in the chestnut forests on the slopes of the Apennines. As we did not know where we were goi.ng, it did not matter where we went and we often climbed in and out of steep valleys in which there were sometimes lovely streams with extremely cold water, but as these afforded the only opportunity of having a bath I steeled myself for the plunge. Occasionally we came across charcoal burners and one night we slept in an outhouse belonging to one of their cottages.

We came to many beautiful little mountain villages where life was fairly primitive and we were always well received. Posty was our initial spokesman and when we arrived at our selected port of call he would pronouce loudly and cheerfully the three quite unconnected words “Io casa Londra”. This formula was intended to convey the information that he lived in London and his hearers generally seemed to infer that that was the case. The next stage in the negotiations was for Posty to produce his family

[Digital page 26]

photographs and these were always viewed with delight as people crowded round, anxious to see and comment on the pictures of the bambini. Cordial relations having thus been established we would be invited to share the evening meal, which seemed nearly always to consist chiefly of polenta. This was. made either from maize meal or from chestnut flour. It was mixed with water to form a heavy dough and then apparently stirred and rolled round in an iron pot over the fire for a long time and finally emptied out onto the wooden table, when it was flattened out·to some extent before being cut into very solid slabs. The maize polenta was exactly like the scalded Indian meal which we used to give to the pigs at Marsh Brook, though that was not cooked after the boiling water had been poured on to it. I did not find it very appetising or very digestible but faute de mieux it was quite eatable. The chestnut polenta was better and tasted rather like a very heavy and stodgy chocolate sandwich cake.

At one farm we went to, the whole family was engaged in tearing the outer covering off the maize cobs and thereby dis lodging the hosts of earwigs· which had taken up their abode inside and which were swarming everywhere like locusts, evidently much alarmed and annoyed at the disturbance.

We were very lucky to have beautiful· weather for our wanderings, but it was becoming too cold to sleep out of doors with any comfort, as of course we had no groundsheet or blanket. We would not in any case have slept in a house for fear of compromising the household, for if any ill disposed person had reported them for harbouring us, they would have been in serious trouble. However we really had to ask to be allowed to come

[Digital page 27]

into farm buildings at night and at the earwig farm we slept in the cowhouse and I shared a stall with a big brown·cow who seemed quite reconciled to my presence. I was a little anxious about whether she would lie down on top of me during the night, as I thought that about twelve hundred weight of cow would be rather flattening, but fortunately all was well and I hope she slept as well as I did.

In the morning, the view was beautiful and most interesting. The farm was high up and looked down into two valleys which converged as they came towards us, with a steep ridge between them. In the morning, the valleys were filled with thick mist and as the sun shone into them, it seemed exactly as if we were looking down onto the sea and the mountain ridge was a headland running out into it.

As we had had such a uniformly friendly welcome every where, I suppose we became over· confident and one day, when we had been living our tramp’s life for just a month and were walking through a rather larger village, we were confronted by two carabinieri. In response to their question about our activities I produced my stock reply that we were going ‘verso Toscana’ which seemed sufficiently vague to cover everything. We thought at first that the police were just having a friendly chat with us, but it gradually dawned on us that we were being arrested, which came as a nasty shock. The two officers of the law were most apologetic and with a wealth of gesticulation gave us to understand that our presence had been observed and reported to them by a Fascist and that they could not therefore avoid taking action. The spokesman covered his eyes and shook his head violently to indicate that, if it had not been for the information

[Digital page 28]

received, he would have taken care not to see us. We were hardly surprised that our disguise had been penetrated, but we regretted that there were still Fascists about.

When we got to the police station there was a charlady there of ample proportions and strong maternal instincts, who loudly bewailed our plight and wept when she realised that we were to be handed over to the Germans. It was all most touching and interesting as an indication of the attitude of Italians in general towards the Germans.

In due course a German truck arrived and we were taken to the Headquarters of a unit which I think was in the small town of Montecatini, where we were handed over to the guard room. We were back in the bag, though this time it was of German· manufacture.

[Digital page 29]

[Image of the countryside surrounding Fontanallato painted by Captain W. (Bill) Glover, which was one of two pictures which Richard carried out of the camp wrapped around a stick.]

[Digital page 30]

[Image of a view of Fontanallato from the top windows of the camp building painted by Lt P.B Swain, who has also been referred to as Paul O. Brien-Swayne. This picture was one of two pictures which Richard carried out of the camp wrapped around a stick.]