Summary of Moran Caplat

An entertaining account of Moran Caplat’s life as a prisoner of war taken from his published biography, “Dinghies to Divas”. A Royal Navy submariner, he and two other officers began their incarceration in Campo 75, Bari, then Campo 38 in Poppi with 50 New Zealanders for about a month before a longer stay in Campo 35 in Padula. This was a huge, rather well-appointed monastery which housed around 500 officers.

Caplat describes the everyday life in camp, the diet, hygiene and meticulous method of fairly sharing the Red Cross parcels. He was very involved in dramatic productions and describes costumes, lighting and set making – and the joint preoccupation with escape attempts which used many of the same materials. He humorously describes debates with the authorities about the Geneva Convention’s lack of rules against knitting whilst on roll-call, or against facial hair. He was unexpectedly repatriated with a number of other Naval officers via a hospital ship to Turkey and there on to a British India Line passenger ship.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital page 1]

[Book cover]

Dinghies to Divas

or Comedy on the Bridge

Some memoirs of a compulsive sailor in troubled waters

Moran Caplat

Collins

8 Grafton Street, London W1

1985

[overwritten in handwriting]

Telegram that M.C. [Moran Caplan] was presumed lost at sea, telephone from relative that Vatican radio had announced he was P.O.W.[Prisoner of War]. Treated well by Italian Navy. Campo 75 Bari. Comparison between individual Officer P.O.Ws. 2 P.O.Ws shot in cold blood. Poppi Campo 38 with New Zealanders. Padula with 500. Almost in ruins P.G.[Prisoner of War] Camp for Germans 1914-1918. Repatriated via Turkey.

[Bottom of page] Roll calls so long some knitted saying it was a British custom.

[Digital page 2]

[pages of a book beginning with chapter 6]

SIX

In the bag

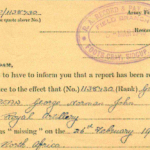

My parents received a telegram from the Admiralty to say that I was ‘missing presumed lost’. My father, so my mother said, was stamping up and down their bedroom saying that he didn’t believe it when the telephone rang. The caller was Diana’s mother. Though not a habitual listener to that station she had by some chance tuned in to the Vatican radio and had heard them read out a list of the survivors from ‘Tempest’. It was this news that she gave my parents just minutes after the arrival of the telegram.

We three officers were now to go to one camp, the twenty petty officers and ratings to another. We were assured that we should be well treated and that there would be regular deliveries of Red Cross parcels, containing soap, butter, tinned meat and other luxuries which the Italians themselves were not getting.

Dressed in our new uniforms of excellent doe-skin cloth we three, under armed guard and in the charge of an Italian officer, were driven in two taxis to the station and put into a first-class carriage with a sentry on each door. Civilian passengers passing down the corridor asked our escort our nationality. On hearing that we were ‘inglesi’, and not ‘tedeschi’, several of them offered us cigarettes and wished us ‘buona fortuna’. Why they thought that Germans might have been travelling under guard I never found out, but they clearly did not like their allies.

Not knowing our destination we imagined that we were being taken to a camp in the north of Italy, but after a journey of only a couple of hours we were decanted at Bari on the Adriatic coast in the south-east of the peninsula. I have been to Bari a good many times since but the impression of that first afternoon remains the same – the heat, the dust and the diminutive stature of the local populace. I am not tall, yet I felt the sort of sensation Gulliver must have had amongst the Lilliputians. Our polite escort took us to the guardroom in a waiting room at the station and formally handed us over to the military police, the carabinieri. That was the end of the politeness.

[page number:95]

[Digital page 3]

The kitting out in Taranto had included not only a uniform suit and cap but a greatcoat and an adequate supply of shirts, socks and underpants. Each of us also had a suitcase. The carabinieri officer spoke no English and I had only basic Italian, having spent two or three weeks on holiday in Italy, mostly in Capri, when I was twenty-one. He made himself quite clear, however. We were to be marched under escort to our camp some two or three kilometres away; no, there was no transport provided, we must carry our own luggage; but, if we had the wherewithal to pay, we could go in one of the horse-drawn cabs – ‘carozze’ – which stood outside the station; our guards would be glad of the ride too. Yes, he would accept the lira notes with which we had been provided in the hospital. We had just about enough between us to pay the exorbitant sum demanded. We did not want to arrive at our “beautiful villa camp beside a lake” looking tired and disreputable. What is more a torrential rain storm was turning the dust into gluey mud and our shoes had been well polished by the hospital orderlies. So in we climbed, the three of us jammed together, two armed guards inside with us and the senior guard on top with the driver under a huge green umbrella. The poor horse which, despite its bells and tassels, didn’t look capable of pulling anything was flogged into unwilling motion by the driver and off we went.

As we proceeded, the surroundings became more and more unpromising. The suburbs were insalubrious to put it mildly and we looked in vain for a lake. Eventually down a narrow, unpaved, rutted and muddy lane, we stopped before an untidy but vicious barbed-wire fence, more of a mad entanglement than anything else, in which was a gate and a guardhouse. Campo 75 consisted of three or four wooden army huts, some smaller buildings and an area of trodden earth become slimy mud in the downpour.

We disembarked, were handed over once again – this time to some singularly scruffy and disgruntled-looking soldiery – and herded to one of the huts. The door was opened and we were bundled inside. The hut was full of iron beds of the most primitive kind, with only a few inches to spare between each; there was a long trestle table down the middle surrounded by benches, and no other furniture. Most of the beds were occupied by British Army Officers, wearing what was left of battledress. A few of them were Sikhs in turbans. There was a general air of despair. The inmates looked with amazement at the three smartly dressed Naval officers with suitcases who had suddenly arrived in their midst. We found three beds and began to take stock.

[page number:96]

[Digital page 4]

The ‘ablutions’, we were told, were in a nearby building. When it was not raining most of the prisoners lay or sat against the outside walls of the hut. There were four roll-calls a day when we had to fall in and be counted outside, and our beds were inspected twice nightly. Rations were miserable, there were no Red Cross parcels, no comforts, no recreation, no books, and though there was a constant trickle of arrival and departure no one seemed to know how long they would be there or where they were destined to go. The commandant was a sadistic bully, many men were lousy, the bedding was never changed.

All in all the Sikhs seemed to manage best. They had several advantages, in that they didn’t miss smoking or drinking, they didn’t seem to mind a diet which consisted of two identical meals a day brought in and dumped on the tables to be doled out with meticulous fairness by the prisoners themselves, and shortage of loo paper didn’t bother them because they were in the habit of using water and one hand, the other hand only being used for eating. Their nightly intoning of their holy offices and the elaborate ceremony of unwinding and rewinding their turbans from day to night wear without at any time leaving the head uncovered, as well as the tying up of their beards and moustaches in white linen bandages before sleeping, caused a certain amount of irritation to their less ritualistic neighbours, but there is no doubt that their morale was as high as their standards – in sharp contrast to the British officer of the Indian Army who occupied the next bed to mine. He had never been without a batman before and was incapable of, or just plain unwilling to try, doing anything for himself. He hadn’t washed, he said, since he had been taken in the desert several weeks ago and didn’t intend to until he got to a decent bath with real soap; when he pulled back his blanket in the morning his bed was so full of leaping fleas that it looked like the top of a glass of Eno’s fruit salts in full effervescence.

The meals consisted of a bowl of thin soup with either a lump or two of nearly raw cauliflower floating in it or four or five inch-long pieces of large-diameter pasta made from some flour that gave them the appearance and taste of coarse brown cardboard. A small army-issue roll of 100 grams of coarse gritty bread, an orange or mandarin, and a mug of coffee substitute – made, we were told, of acorns and sweetened with some sort of saccharine — completed the feast. Hunger led to my eating the citrus fruits whole, skin, pith and pips as well as the juicy part. I developed such a taste for the zest that I now enjoy the peel more than the middle, and particularly like the

[page number:97]

[Digital page 5]

bitter taste of the pips. We also got five cigarettes a day: called Milits, they came in little blue-paper packets rather like old-fashioned Woodbines. They were standard issue to the Italian Army, hence their name, but we were all convinced they were made of dried millet. They became currency, exchangeable for oranges or used for gambling.

This diet quickly sapped one’s strength. We three arrived fresh and well, whereas most of the soldiers were already weak and dispirited before they got there. Two of them did make a break for it, however. Early one morning they found a way through the wire but were quickly picked up and brought back into camp. The comandante made us all fall in and had the two men marched before him by a posse of the miserable Italian soldiery with fixed bayonets. The order was given for the guard to load their rifles. One poor wight undid the ammunition pouch on his equipment to get the clip of bullets but unfortunately for him produced a packet of Milits by mistake. The comandante let out several hysterical screams and the man was despatched to the guardroom. Whether it was this incident that further exasperated the colonnello, I don’t know. He next ordered the two escapers at the point of the now loaded rifles to demonstrate exactly where and how they had got through the wire. I discovered from some of their friends afterwards that they did not want to indicate the hole they had found in case some others could use it. Instead they approached the wire in one corner and started to climb through it as best they could. They became totally stuck and the enraged comandante ordered his troops to fire. Obviously shocked and unwilling, they hesitated, only to be screamed at again. Then they fired and killed our two fellow-prisoners before our eyes. We were herded back to our huts and locked in for the rest of the day. The two men were accounted for as having been killed trying to escape — as would anyone else who tried it, said the comandante, through an interpreter at the next roll-call. He got his deserts, however. I believe he was one of very few to be tried, convicted and executed after the fall of Italy.

After two or three weeks I suffered a recurrence of the tonsillitis which was apt to hit me whenever I became overtired or run-down. This occurred always at awkward times, particularly when I was acting. The fashion in my youth was against tonsillectomy and I did not have mine removed until I was in my early forties. Since then I have never even had a sore throat and wish that I had been spared tbe agonizing attacks from an earlier age. This latest attack struck just as word came that I and a few others, including

[page number:98]

[Digital page 6]

my two shipmates, were to be moved to a ‘permanent’ camp, Bari being considered only suitable for transit.

No horse-cab this time; we were marched to the station, made to wait what seemed hours in great discomfort, and bundled into a train with wooden benches and the doors and windows tightly locked. By now I was feeling really ill. I had a high fever and could not speak or eat. It was late March and very hot. At Rome we changed trains and guards and were allowed under escort to go to the loo. I remember, through the haze of my fever, the shock I got when the woman attendant in that station lavatory issued me with three sheets of bumf and sat on her stool and watched me through the door kept open by my guard. From Rome we went to Arezzo and had another dreadful wait in a filthy, hot and airless waiting-room for the army lorry to come to take us to our new camp. By the time I got there I really thought I was going to die, and indeed might well have done so because I had developed a full quinsy and could barely breathe. I was rushed to the sick bay and an Italian doctor thrust a wooden spatula down my throat, causing me great pain but doing little else. There were two doctor prisoners there, however, and they nursed me and dosed me through the next day. The following night I had a fit of retching and disgorged a disgusting lump of infected material. This apparently did the trick and I soon recovered.

I found myself in Campo 38 in a house on the top of a fairy-tale hill at Poppi in Tuscany. The house was the summer residence of an order of nuns, from Florence I believe, who were remaining in their winter quarters. It was plainly furnished but clean and spacious and we were only four or six to a largish room. My fellow prisoners this time, apart from the few who had come with me from Bari, were all New Zealanders. Some fifty or so as memory serves, they were all of the same unit and had come from New Zealand to fight in the North African desert. None of them except one who had been a professional tennis player had ever been in Europe, still less England which they nevertheless constantly referred to as home.

They were avid for information; every evening groups of them gathered around to hear the most simple facts about the ‘sophisticated’ life of London. One of them told me that his greatest dream was to go out to dinner and a theatre. ‘But surely,’ I said, ‘you can do that in Auckland ?’ ‘No,’ he replied. ‘First there’s very little theatre there and never seems to be any when I get to town, and second we don’t have dinner in the evening, we only have high tea.’

[page number:99]

[Digital page 7]

If this camp was not the “villa by the lake etc” that we had been promised, it was quite civilised. Red Cross parcels appeared, not one per man per week which was the aim but, with reasonable regularity, one between four per week. Containing Klim powdered milk, sugar, cheese, tomato puree, soups, Ovaltine, cocoa, tea and a variety of ‘goodies’ including hotel-sized tablets of real soap, they provided us with necessary vitamins and a great deal of interest. The division into four parts was here, and in my next camp, a ritual conducted with strict impartiality. Anything once opened had to be consumed fairly rapidly; there were no refrigerators and not much in the way of storage space except the cardboard boxes themselves. To divide a tin of butter into four involved the following procedure: 1. Open the tin with the key provided on the side (a crucial operation needing concentration and skill since we had no alternative tool if, as often happened, the key broke). 2. Turn the butter out on to a plate belonging to one of the four – we took it in turns to provide the plate as this offered the bonus of a slight residue. 3. Cut the cards (we not only managed to get a few packs from the Italians but we made our own out of Red Cross cardboard boxes and packaging) to decide who should divide the lump of butter into four as far as possible equal parts. 4. Cut the cards again or draw straw lots to decide the order of precedence for selecting whichever of the four portions looked fractionally bigger. 5. Draw again to decide who got the empty tin, itself a valuable commodity. Variations on this basic procedure were followed for everything in the parcel; even the cardboard box itself was either carefully divided or drawn for.

At Poppi there was another attempt at escape. Standing as the house did on a hill, it was surrounded first by a wall and previously well-cultivated kitchen garden, then by a steeply terraced vineyard. As it was early spring, the vineyard was being turned over by pairs of big white oxen controlled by a beefy lady uttering strange cries. The wall had barbed wire on it and there was a sentry box at each corner with searchlights that swept around at irregular intervals. Three of the New Zealanders managed to conceal themselves in the garden before we were locked in for the night, having planted dummies in their beds to deceive those counting heads on pillows, but the morning roll-call was three short and the alarm was given by ringing the chapel bell loud and long. The three had succeeded in climbing the wall and negotiating the wire, but it had taken them a long time and at daylight they had gone to ground in the vineyard.

[page number:100]

[Digital page 8]

They were ill-prepared for escape, having only the battle dresses that were normal prison wear, and no faked papers or maps, nor much in the way of rations. The peasants who might have helped, and on whom the escapers were banking, could and would do nothing once the alarm had been given. Hiding under a terrace wall the three were faced by two snorting oxen, a plough and a large lady, and decided to call it a day. Back in camp they were put in a separate room and were only allowed to be visited by their own senior officer with an interpreter present. They were not otherwise ill-treated, however, and were transferred to one of the high-security camps which were rapidly becoming full of similarly adventurous and determined fellows.

In mid-May, after I had been there just a month, the authorities decided that they had not meant to send a few miscellaneous Englishmen to join the Kiwis and we were moved once more. Though news was hard to come by we were getting the message that things were going less well for the Axis in Africa and we lived in constant dread that we should be moved further and further north, eventually perhaps to camps in Germany. Consequently I was surprised to find myself once again at Arezzo station and heading south, no change of train in Rome or Naples, on through Battipaglia and then, just as dawn was breaking, turned out at the little station of Padula. It was wonderful country again, bleached and barren after the green hills of Tuscany but with a marvellous clean and classical light, the little hill villages dotted around a central plain. A march of a kilometre or so with baggage on a cart behind and I found myself at the imposing gate of a vast and beautiful building, the Certosa di Padula. This important Carthusian monastery had become Campo Concentramenta di Prigonieri di Guerra Numero Trenta Cinque,

The cloisters, said to be the biggest in the world being some quarter of a mile round, had opening off them on ground level a number of separate residences for its original senior and wealthy inmates; we called them ‘quarters’. Each of these consisted of an entrance hall, two large rooms and a long passage leading to a loo. Each quarter also had a small walled garden entered by a flight of stairs from a terrace outside the living-rooms and further enclosed by the wall of the next quarter on one side and the passage and loo on the other, with a high wall at the end which was part of the main wall of the building. Beyond this wall were the fields of the monastery, themselves surrounded at a greater distance by the boundary wall of the whole estate. The level of the ground in the garden was

[page number:101]

[Digital page 9]

considerably higher than the surrounding fields so that what was a three-metre wall from inside was at least another couple of metres higher on the outside. The gardens were irrigated by a system of pipes and channels in the outer wall fed with water from a spring in the hills behind the village.

The monks who originally occupied these quarters were obviously prepared for clandestine visitors as there was a small door and a flight of steps from each garden to the greater world outside. When it was turned into a prison the doors were bricked up, the garden walls provided with barbed-wire tops, and sentry boxes with searchlights provided at frequent intervals round the perimeter, which was marked by more barbed wire.

Above the cloistered walk was an ambulatory, a covered walk for bad weather with big windows opening on to the central courtyard. The main staircase reaching this from one corner of the cloister was a fine marble spiral one with open windows giving a view of the countryside; below this a barbed-wire enclosure the size of a football field was provided for exercise. No windows either on the ground floor or in the ambulatory looked on to the outside world. The only ones that did were tiny squares cut in the loos from which, by gripping the sill and hauling oneself up from the non-existent seat, one could look out of the unglazed barred window. Straight ahead was a field of maize standing some ten metres away from the wall; inset into the edge of the maize was a continuous barbed-wire fence and one of the sentry boxes. Somehow, whenever I looked out, it always seemed to be occupied by the same little soldier busy masturbating before the sergeant came round again.

The ambulatory was made into four dormitories which we called ‘wings’. There were some five hundred officers in the camp, a mixed bag from all the services with the Army in the majority and the Navy and R.A.F. about equally represented. There were also some fifty other ranks who acted as mess orderlies and worked in the kitchen. These were volunteers, as I understood it, who had decided that they would rather work in the officers’ camp than do the less menial but more boring work that was meted out to them in the men’s camps. They also got a bit of extra money and some of them no doubt felt that their chances of escape might be better.

Discipline amongst ourselves was good. The camp was well run by a committee of the three senior officers of each service, under the overall command of the senior British officer, Brigadier Mountain. The more junior officers were billeted in the four ‘wings’, each under the charge of a ‘wing-commander’, and the

[page number:102]

[Digital page 10]

more senior in the ‘quarters’ with some ten or twelve officers to each. I apparently just qualified for a quarter and was pleased to be there.

Meals were taken in two or three sittings in the big refectory, a fine room which we also used as a theatre. It opened directly off the cloister on the south side. Beside it the old kitchens with their huge wood-fired coppers and stores were brought back into use for us; the walls were tiled in a virulent yellow-and-green checked pattern which was said to be efficacious in keeping out unwanted flies and wasps. Next to the kitchens were rooms fitted up for mass showers, with twenty nozzles in the ceiling controlled by a guard who could be sadistic in the sudden change from hot to cold or vice versa.

Food was less good and plentiful than in Poppi but still a lot better than Bari. The all-important Red Cross parcels arrived in big loads but spasmodically and we imposed our own rationing system, which sometimes meant divisions into portions even more scrupulously meted out than in Poppi. A small proportion of the parcels were ‘medical’, designed for the weak and feeble with things like calves-feet jelly, beef tea and vitamins such as Bemax. These were handed over to the doctors amongst us to administer as needed. The only mishandling, if that is the word, of these that I recall came about when a certain prisoner, thought to be short of Vitamin B was put on a crash course of Bemax. The unfortunate result was acute discomfort and inflammation of the penis brought about by having a permanent and relentless erection in contact with rough prison blankets. A reduction of the dosage brought relief in more ways than one.

When I got there the only theatrical entertainment being organized was a camp concert — ‘camp’ in both senses — in which such inmates as could remember any of the words strove to emulate the music-hall entertainers of the day, particularly of course the Crazy Gang and Max Miller. Dressing up as best they could with Klim tin lids as brassieres, they cavorted about in clumsy imitation of the Tiller Girls.

Some of us thought we ought to go for more sophisticated theatrical enterprises. The first improvement I made was to direct a mixed bill of scenes from Shakespeare, all chosen for male parts only, in which I performed Richard in Richard III and Bottom in the play scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Two distantly related Johnstons — Johnny of the Indian Army and Gordon of the 60th Rifles, the first as author and lyricist, the second as composer-

[page number:103]

[Digital page 11]

set to work on a musical comedy entitled Be Brazen which I was to direct. The opening chorus began: “At seventeen Clover Street, Right next to Dover Street…” which will give some idea of the style and location of the piece. In the event it was a huge success. A small charge was made for the tickets, and by the last performance the black-market price was twelve times its face value; there was even talk of putting the show on in London for charity when we got back.

Our ideas were ambitious and involved the purchase with camp funds, which were a levy on everyone’s pay, of large quantities of dress materials, electrical flex, bulbs, bulb holders and plugs, all of which we were allowed to have for the purpose of improving the stage and lighting effects in the refectory. The camp itself was supplied with a rudimentary sort of electric lighting coming from a generator in the village above and failing every time there was one of the not infrequent thunderstorms. It was direct current run on two wires loosely attached to the walls and with switches that worked, when they did, in the opposite way from normal. The searchlights on the perimeter were run from army generators and were not susceptible to failure from local causes.

Escape was never far from the minds of some of us, and it was decided to make a tunnel from the garden of our quarter No.5 out into the maize field at the back of the sentry box. We were alredy gardening hard in the little enclosure with seed bought through the extremely pro-British interpreter. (He had worked as a waiter in England and dreamt of retiring there, after “we” had won the war, to open a restaurant to which naturally all his distinguished friends, ex-prisoners-of-war, would flock.)

The escape scheme involved making a tray about three feet by two, six or eight inches deep, out of wood purloined from the kitchens and elsewhere. This was filled with soil and buried just below the surface of the garden, up against the side wall and some distance back from the end wall. Under it a manhole was excavated, shored up with anything that could be found, and from this a tunnel, just big enough for a man to wriggle along on his stomach, was begun at an angle calculated to take it below the foundations of the end wall, after which it would level out and go under the barbed wire into the maize field. The tray was kept planted with tomatoes and was lifted out immediately after roll-call, when a man went down. Roll-calls were at fixed times and it was possible to get the man out, put the tray back, cover the traces and have everyone on parade before his absence would be noted. There was,

[page number:104]

[Digital page 12]

however, the danger of a spot check between roll-calls, and for this reason there were always two or three prisoners busily at work in the garden ready to take immediate action should one of the Italians enter the quarter.

As an extra activity we kept rabbits on the terrace from which access to the garden was gained. Discussion of their ailments and breeding capacity with any visiting Italian was calculated to give the gardeners enough time to get the tray in position and cover up. Only once did this actually happen; the discussion revolved round the fact that the enormous rabbit we thought to be the buck had just produced a litter and the buck was therefore the diminutive frightened object at the other end of the cage — a situation which led to much joking to the Italian taste. The gardeners hastily clapped the tray over the miner in his narrow, unventilated and unlit burrow. The jokes went on and on, the visiting Italians at last departed with aching sides, no doubt to regale colleagues with the success of their racy remarks with the normally po-faced English. When the immolated miner was at last recovered he had to have artificial respiration to get him on parade in time for the next roll-call.

Digging in this tunnel was slow, mostly done just in front of the digger’s face with a tablespoon; the tin he thus laboriously filled was passed back between his legs to a gardener by the manhole, who then scattered the earth as casually as possible. By the time the outside wall was reached it was clear that the tunnel was too small and not deep enough. Although a primitive pair of bellows had been constructed to pump air down to the worker through a tube made of old tins, it had become impossible to stay at the face for more than a few minutes at a time.

Somehow the game was given away. How they thought of it we never knew but one day an Italian search party appeared and a spot roll-call was made. They entered our quarter with spades and quickly discovered the lid and what was beneath. We were given a minor punishment in the temporary removal of some privileges and extra roll-calls, and thereafter the gardens were gone over daily with long steel probes. No one had escaped, the Italians’ honour and reputation had not been put in jeopardy and no higher authority had to be called in, so the matter was soon glossed over.

Roll-calls involved falling in, in squads of not more than fifty, under the arcades of the cloister. The nominal roll was called by a British officer, then two soldiers counted each group, one watching while the other walked backwards and forwards between the lines

[page number:105]

[Digital page 13]

of prisoners, solemnly counting off each one. The soldiers counting carried their rifles with fixed bayonets slung on their backs, the tip of the short blade being just above their head which was in turn generally rather less high than ours. A favourite trick was to write some schoolboy-like derogatory remark on a piece of paper and impale it on the bayonet point as the soldier went by without any of them realizing where it came from. The Italians were understandably annoyed and stamped out the practice by keeping the squad concerned on parade for another hour or two.

Amongst the Red Cross comforts and the occasional personal parcel from home were a number of hand-knitted garments, such as mittens, scarves and sweaters; these were sometimes of a size or shape that was not entirely to the liking of the recipients. Our Senior Naval Officer was adept at knitting and started a class to teach others. Wooden knitting needles were available and wool was obtained from unraveling worn-out garments. One day, to the fury of the camp commandant, the Naval knitting class went to roll-call each with a ball of wool in one breast pocket of his battle-dress and needles sticking out of the other. A good part of our roll-call time was spent ‘at ease’ and we all started to knit, putting the gear away whenever we were called to attention. Will Scarlett, our teacher, was summoned before the comandante but was able to argue that there was nothing in the Geneva Convention to prevent officers knitting while at ease and, with less truth, that it was common practice in the Royal Navy. No disrespect was implied, he said, indeed perhaps the comandante himself would care for a little slip-over or even a tie? After that no more was said, though the practice diminished as winter came and fingers were too cold.

Another appeal to the rules of the Geneva Convention arose over our retention of beards. The Italians decided to issue each prisoner with an identity card which included his photograph. The principal reason for this was obviously so that, if we did get out, we could be identified. To this end they demanded that all prisoners should be clean-shaven before being photographed. We refused, the Army and R.A.F. claiming that moustaches were permitted to them and the Navy that beards and moustaches, provided no part of the face was shaved, were acceptable adornments. So we kept our whiskers, knowing full well that their removal was the quickest and most effective way of assuming a disguise. Our projects for the theatre were a considerable help to the escape industry. The escapologists and the escape committee decided to make a more efficient attempt at another tunnel. Quarter No.6 was chosen, as

[page number:106]

[Digital page 14]

were a couple of dozen of those keenest on escaping. The idea was brilliantly simple. The loos at the end of the passages and against the outside walls were originally nothing more than six-inch holes in the floor which gave access to a large windowless and doorless basement beneath. The far end of the cellar directly under the hole had in early times been dug out in a deep pit into which anything dropping from the hole above would be absorbed in cool and earth-bound darkness; no doubt noisome and insalubrious enough in its day. When the near-ruined certosa, long since out of use for its original purpose, had been adapted as a prison camp, flushing cisterns worked on the old irrigation system for the gardens had been established over the holes, two ‘foot-prints’ supplied beside them and a waste-pipe run direct from the holes via a U-bend to a new but rudimentary drainage system at a shallow level all round the walls outside the perimeter. All this had been found out by our continuous exploration trips, and digs and soundings were made in order to learn exactly how the complex building worked. Night-time trips over the roofs had shown what lay beyond the area we inhabited, and careful soundings of walls and floor were equally revealing. One of the latter led us into the big cellars under the quarters.

Once again a tray was made, this time in the tiled floor of the loo passage, and cleverly camouflaged and insulated so that it sounded no different from the rest of the floor if struck. Dropping through this trap door by means of a rope ladder made of carefully hoarded string, one could reach the ample space below. Down in the corner, under the hole which now had its own connection through the wall to the new drainage system, ideal conditions existed for quick and silent digging.

The old ‘long-drop’ pit was found to be full of two hundred year-old monkish ordure which had matured into an odourless fibrous mass like dried peat. It could be cut into neat blocks with a knife and removed to the back of the cellar. This led down, making a four foot square wall, to below the level of the wall’s massive foundations. Tunnelling under these was easy; there was no need for pit props until the hard clay ground of the field was reached. A four foot square tunnel was big enough to kneel in and wield a makeshift pickaxe. A little railway was set up on wooden rails made of battens acquired for the theatre, on which a truck carrying several bucketfuls of spoil at a time could be hauled back and forth. Electric lighting, ‘borrowed’ from the theatre, and the size of the tunnel together with the air space of the cellar, made ventilation

[page number:107]

[Digital page 15]

less of a problem than in the earlier tunnel, but a more sophisticated pump was made and operated. Noise was of little consequence due to the thickness of the walls until near the end some yards into the field of maize, which itself would not be cut for some time yet. The spoil, what seemed like (and probably was) tons of it, was easily accommodated in the enclosed cellar. As many as six men could work at a time, two taking it in turns at the face, one working the railway, one dumping the spoil and two on watch outside. It was even found possible to cope with roll-calls occurring at short notice, so good was the drill.

Meanwhile the escape industry was growing. Cooking facilities for dealing with Red Cross parcel food were initially non-existent but some became expert at making stoves or stufas — at first simple braziers and then sophisticated contrivances made out of empty tins that were capable of boiling a tin of water in three minutes on the fuel provided by one end of a cardboard Red Cross parcel box. Even ovens were made. The expert craftsman was ‘Fingers’ Lewis, a small dark bearded Welshman from the Fleet Air Arm who was a wizard with a tin, a pair of scissors and a small hammer. His biggest effort was almost an Aga in size and efficiency. The Italians did not seem to mind this; the stufas were used quite openly, and only when some unappreciative souls started to break up beautiful old walnut doors and panelling in the effort to keep warm in winter did the Italians get cross. In these stufas iron rations of cocoa mixed with powdered biscuit and raisins were baked hard and hidden away for issue to escapers when needed.

Documents and passes were painstakingly forged, each letter being cut in cork and stamped by hand. Needles were magnetized and turned into compasses; maps were made by piecing together information gleaned from many sources or simply from memory. Clothes were altered and adapted most ingeniously.

Finally the tunnel was ready, and lots were drawn to decide the order in which the first dozen should go. It had been calculated that, with a bit of luck, twelve people could have dummies substituted in their beds to deceive the night-time checks. The twelve would be hidden in the cellar when the quarter was locked after lights out, and ten others would occupy the quarter itself. The chosen twelve would get out of the tunnel, leaving those in the quarter to make everything appear normal. If, by some miracle, the cover-up plans were successful, a further, larger party would go the second night, after which concealment would be impossible. All this worked perfectly and the twelve were despatched soon after dark.

[page number:108]

[Digital page 16]

My task was to follow the twelfth man down the tunnel, see him out, help him from inside to conceal the exit as far as possible and return to the quarter. That was as far as I ever got towards a successful escape. I did just get my head out into the field before putting strutting and boards up for the last man to cover over as best he could.

Alas, at the midnight round of the dormitories one of the dummies was discovered. The Italians went mad and turned the place inside out. At first they thought that so large a number could not possibly have left, and searched the buildings high and low; then, realizing that most of the missing men came from quarter No.6, they broke into the cellar through the side wall and all was discovered. They did not enter the tunnel themselves, they merely took a hose and flooded it, then cemented the floor over and did the same in all the other cellars.

We never saw the escapers again but were told that they were all recaptured, mostly near by, though three did get to the coast near Bari. We always imagined that it would be possible to get to the coast somewhere, steal a fishing boat and try to reach Malta or Jugoslavia or even North Africa. In fact all the boats were closely guarded and as far as I know this plan never succeeded. The very few escapers to get out of Italy before the Allies invaded the country spoke reasonable Italian, managed to get on to trains going north and then, either bluffed their way with forged documents over the frontier to Switzerland, or jumped off the train and did the last part on foot. Once Italy began to crack under the invasion, the prisoners from Padula were loaded on to trains and taken into Austria; quite a few managed to elude the guards, however, and were sheltered by Italian civilians, until at last the advancing Allied forces retrieved them.

Those of our escapers caught near by were returned to the camp for a few days’ interrogation before being sent to a higher security prison in the north – the notorious Campo Cinque, a sort of Italian Colditz near Genoa. They told our senior officer when he was allowed to see them that their interrogation had been relatively mild, the main question being whether they had had any contact with Italian civilians. The interrogators were apparently of the opinion that as it was clearly impossible to get out of Italy, the only reason to leave so comfortable a prison for the rigours of life in the countryside was a sexual one. They were convinced that the fugitives must have made a bee-line for the first woman they could get to.

[page number:109]

[Digital page 17]

Apart from a tightening up of regulations, the withholding of parcels, locking up of all theatrical equipment when not in use and a change of comandante, little altered in our way of life as a result of this episode.

Emboldened by the success of female impersonation in Be Brazen — indeed the leading ‘lady’ and some of the chorus girls became camp celebrities overnight — I suggested that, since Shakespeare had done his plays without women, we could now tackle a complete play. We were able to get books through the Red Cross and there was no great difficulty in coming by the classics. I kicked off with my old favourite, Twelfth Night. I decided to set it in Ruritania, which meant that by a judicious admixture of the uniforms of three services plus some fanciful additions in the form of epaulettes, sashes and headgear, quite a lot could be achieved.

My two dressmakers, hefty antipodeans who had worked in a fashion house in peace-time, did wonders for the women’s dresses. I was lucky too in my cast. George Millar, the writer whose book Horned Pigeon has his own account of life in Padula, was blessed with a roseate complexion on a fair and delicate skin and extremely shapely legs, and made a wonderful Olivia. At least he did so up to the penultimate rehearsal; with my agreement he used this activity as a cover for the fact that he was about to escape. We had an understudy ready and the show went on as planned. Father Hugh Bishop, later to become Superior of the Mirfield Brethren and later still to take the bold step of ‘coming out of the closet’, was a dignified and mellifluous Orsino. I had a wonderful Feste in Gordon Johnston, who also set the songs to music for the production. My Aguecheek was ‘Oily’ somebody – the name is gone from me but the memory of his high-class inanity lingers on – and my Toby Belch was Neville Lloyd, a great motor-racing authority, now alas no longer with us. All in all Twelfth Night was a triumph, and all the innuendoes in Malvolio’s speeches went over with an impact surely unknown since Shakespeare’s own time.

We had such a mixed bag of inmates that there was always some new interest, and when things were comparatively quiet the guards, or more particularly the interpreters could be persuaded to bring in the occasional newspaper. The Red Cross provided a gramophone and classical records. Study groups were set up on all kinds of subjects and lectures given.

After the tunnel incident, the quarters were temporarily closed and the inmates dispersed to the dormitories, adding considerably to the existing congestion. I became ‘wing-commander’ for the one

[page number:110]

[Digital page 18]

into which most of the theatrically minded made their way. Our end of it in particular became known as Greenwich Village. In those days this carried no other connotation than ‘Bohemian’. Indeed at no time as a prisoner-of-war did I come upon any overt homosexuality. There was little privacy to permit any ‘acts’, however consenting the adults might have been, and, though there were some close friendships struck, sex as such was not an important topic – perhaps the diet was too low.

The prisoners’ ‘shop’ varied very much in what it could supply in return for camp money. We got a small ration of terrible red wine most of the time; sometimes it was stopped as a punishment, sometimes it just ran out. Occasionally there were deliveries of a particularly sweet and sticky Marsala; once one of the interpreters whose ‘uncle’ made condensed milk, negotiated for us the black-market purchase of four huge wooden barrels of a turgid yellowish goo such as M. Nestle never knew. The barrels were driven into the courtyard on a bullock cart. Three were successfully unloaded and rolled into the canteen; the fourth fell off, exploded and mingled with the dust in a huge puddle. Eager prisoners rushed out with any receptacle they could find and scooped up as much as they could. Flies and wasps arrived in myriads — we were never short of either — mosquitoes too, and ants in armies. It took several thunderstorms to wash the mess away. Just before Christmas the shop astonishingly received an enormous black-market consignment of talcum powder, which a lot of people found a welcome luxury since there was more in our surroundings to chafe than to soothe.

Wine was hoarded for Christmas, and delicacies from Red Cross parcels. Some people managed to ferment strange liquors from raisins or other dried or tinned fruit, and the Italians on Christmas night wisely suspended the usual ten o’clock curfew until after midnight and kept themselves out of the interior of the camp. Festivities began, and eventually most of the inmates were well away. There was a fancy dress parade and the whole thing culminated in a procession, singing and dancing its way round the wings. Suddenly somebody said, “Let’s have a white Christmas”, and emptied his large box of talcum powder over his neighbours. Soon the idea spread and the whole place was covered in it. This resulted in a fearful mess that took a lot of cleaning up.

Apart from Christmas the winter was cold and dreary and the heating was not much use; it consisted of just a few La Boheme-type wood-burning stoves with pipes out of the ill-fitting windows.

[page number:111]

[Digital page 19]

After the tunnel incident, thoughts of escape went in different directions and the escape committee had many proposals put before them. Most of these were turned down as being impractical or ‘not in the public interest’; there was after all a big lobby in the camp that preferred to be on good terms with our captors, believing escape to be a near impossibility for anyone and a total impossibility for them personally.

One of the keenest would-be escapers was George Millar. George was a great individualist. Not for him the mass escape, though he was concerned in both tunnels. During the hard days and longer nights of the winter he carried out a series of exploratory trips over the roofs of the big kitchen, the refectory and the old library. This latter was out of bounds to us though some did get into it over the roofs. It was full of great leather-bound tomes rotting away behind wire-mesh doors in huge walnut bookshelves.

George established a lot of interesting facts which he kept to himself until his plan was complete enough to put to the select few of the escape committee for approval. Behind the kitchens there was a small courtyard surrounded by the old stables and domestic outbuildings which were now in use as barrack accommodation for the soldiers and guards. George found a perilous route over the rotten roofs which would allow him to get into this courtyard. The big gates in an arch in the wall which led to the road outside stood open by day with a guard on duty. The main iron gates from the outer courtyard to our cloister (over which was a Latin inscription to the effect that all who entered here renounced the world for ever) were heavily guarded and lit at night. There was no way through them for a prisoner unless he were under escort. George’s idea was simple and daring. He and his three companions were to disguise themselves as Italian soldiers and, by way of the roofs and a route they had explored, to get into the guards’ part of the building. Then they would just walk out of the front gate, choosing the late afternoon hour when the day and night shifts were changing and it was normal for soldiers to go casually out of the gate on their way to the village without having to show papers. The four would then make their way on foot to one of the air-strips that had been set up in the area to counter the expected Allied invasion, seize an aircraft and fly to North Africa. George was the brains and he had chosen a pilot, a radio operator and a strong and ruthless hit-man to go with him.

The uniforms were concocted from old Italian uniforms issued to prisoners with defacing grey patches on the sleeves which were

[page number:112]

[Digital page 20]

ingeniously covered with black cloth to make them look like mourning patches such as were commonly worn. All went according to plan, and they were nearly through the gate when someone spotted that they were wearing the wrong boots — English boots.

After their recapture they were taken into the punishment cell near the main entrance and stripped. A message came through that they would not be returning to this camp and their personal belongings were to be taken through to them. George was a ‘Greenwich Village’ inhabitant and I as his wing-commander was deputed to gather up the gear he had left behind together with that of his companions and hand it over to the authorities in return for a proper receipt. I found myself in the ante-room of the punishment cell and could see through a crack in the door that the four were standing naked, with the comandante raving at them and hitting them between shouts with a heavy metal-bound ruler. I was given a receipt by a sergeant and hurriedly bundled away. I did not meet George again until years afterwards on a yacht in the Beaulieu River.

After Twelfth Night I tried my hand at producing a thriller, I Killed the Count, which helped to pass the time, and by early April 1943 we had got as far as the dress rehearsal of another musical comedy. This was to be bigger and better than Be Brazen and was put together by the same team. Unfortunately I have forgotten its name and much about it. I do remember, however, that Gordon dubbed me ‘Doves-with-Everything’ Caplat because of my wish for elaborate staging. (I had to wait for Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail in my last year at Glyndebourne actually to get doves on the stage in any numbers.) It was after the evening meal and before the ten o’clock curfew, when the unpleasant interpreter who had been a coal merchant in Cardiff burst in to the theatre-cum-refectory and told me that the comandante wanted to see me immediately. ‘Go away,’ I said. ‘I’ll come when the rehearsal is over, not before.’ ‘You must come now. It is very important!’ ‘No,’ I said again, and he sat there fuming while we finished. Excitedly he led me to the office and there I was told that I and three other naval prisoners were to be repatriated and that we must be ready to leave at four o’clock next morning. Dazed, I reported back to my own senior officer.

No reason was given for our selection; it seemed to be an arbitrary decision. We were not the most senior, nor the least, we were not ill. Nobody could offer an explanation except for the fear at the back of all our minds that sooner or later we would be moved to

[page number:113]

[Digital page 21]

Germany and that this might be the first of a series of ruses to get us to “go quietly”.

In the next few hours we were kitted up by the escape committee; that is to say we were given tissue-paper maps to aid us if we were able to get off a train or otherwise elude our guards, compasses hidden in boot heels, and some of the precious cakes made with cocoa, Ovaltine and butter from the parcels. There was no time to get any false documents even if we had known what we might need.

At 4am we presented ourselves at the main gates. Outside in the courtyard was an army truck, a surprise as it was normal for prisoners arriving or departing to be marched to the station. An officer and four guards came with us and treated us with unusual politeness. On the train we were put into a first-class compartment and to our surprise again the train set off not to the north but in an easterly direction. Incredulous though we had been when we started, we began to think we might have been told the truth. At Potenza, that Crewe of the Mezzogiorno, we had to change trains. We learnt that we were off to Bari, where a hospital ship awaited to waft us home. Now we became very keen not to lose our guards. Far from wishing to get away we were concerned not to be left behind.

Bari of the hideous memories of a year ago was still a transit camp, but it had been cleaned up and improved facilities greeted us everywhere. We found ourselves part of a rapidly growing collection of navy personnel – officers and men drawn from camps all over Italy, all equally bemused by their sudden change in fortune. The ship, we were told, was in the harbour. We would go on board that evening. Meanwhile a scratch meal and wine was offered and the inevitable documentation hurried through. We also had to be searched before going on board. Now began a series of visits to the loo, not only from excitement but also to dispose of our escape gear before the search. Maps were eaten or flushed away, compass needles disposed of, iron rations consumed; only a little hoard of Red Cross cakes of soap, the highest barter currency available to us at the time, was retained. We need not have worried. The search was cursory, we were embussed and taken to the docks, and there was the hospital ship ‘Gradisca’.

Gleaming white with red crosses on her funnel and on her sides, old but elegant, she awaited us. Ushered on board by stewards, we sorted ourselves out. Five of us were submariners and succeeded in getting a cabin togeher. The ship was crowded but

[page number:114]

[Digital page 22]

there was a festive feeling in the air. We would sail at about 9pm and dinner would be served. We were back in the gracious atmosphere of the naval hospital at Taranto but with one even more astonishing difference — there were women on board. These were voluntary nurses, not the lower orders of staff but in the upper echelon of the Italian Red Cross. All of them were ladies of distinction, some titled, most spoke excellent and charming English, and some of them knew England well and found friends among our mutual acquaintances. It was like a mad dream, the transition was so great and so fast.

In the morning though we, the submariners, began to get nervous. It was obvious that we were steaming east, unescorted, not zigzagging. Rumour correctly had it that we were heading for Mersin in neutral Turkey, but we realized two things. First, we could see the high land of Crete to port, so we were out in the open Mediterranean; secondly, we knew that the British were justly suspicious of the uses to which the Germans had put Italian hospital ships in ferrying their troops to and from Africa. We thought of our colleagues at sea and prayed that we would have a safe passage and not get torpedoed by one of our own boats. I remembered how ‘Tempest’ had so nearly attacked a ship given safe conduct.

We pooled our Red Cross soap packets and with them bought copious supplies of wine from the stewards. We got as high as decency allowed, so that our conversation with the ladies of quality at mealtimes was balanced on a razor’s edge, but we survived.

Two days later in the early morning the ‘Gradisca’ anchored in the bay of Mersin. She must have looked more like a large private yacht or a cruise ship than anything normally seen in war-time. On the other side of the bay, perhaps half a mile away, was anchored a British India Line passenger vessel — sleazy, old, but, and this certainly cheered our hearts, flying a tattered red ensign.

The Turkish Red Crescent appeared in a launch bringing us, unbelievably, a consignment of Turkish Delight and Turkish cigarettes. After some delay the Turkish Navy appeared, in barges manned by piratical-looking crews with bare and horny-toed feet. We were ferried to the old ship with the red ensign, the ‘S.S. Talma’.

In April 1941 three Italian destroyers had scuttled themselves in Saudi Arabian territorial waters and the crews were interned on an island off Jedda. The large numbers caused considerable embarrassment to the Saudi Arabian government. The German advance on Alexandria was in progress and the presence of eight

[page number:115]

[Digital page 23]

hundred hostile naval personnel on British lines of communication was a cause for anxiety. The neutral Turks enquired whether Britain would agree to the Italians being transported under safe conduct on a British ship to a Turkish port. H.M.G. [His Majesty’s Government] quickly concurred. The Italians were taken from Jedda in the ‘Talma’ and the day before she arrived in Mersin an Italian bomber dropped a stick of bombs on her. Luckily all missed, but the Italians on board, who had been pleased to see one of their own aircraft, were somewhat downcast by the event. Had any of the men on either side been sick or wounded and repatriated under the Geneva Convention they would not have been allowed to return to active service.

Once on the ‘Talma’ things changed again. She was as tatty below as on deck and there were no ladies to welcome us, but the old first-class saloon bar was just as it had been for years throughout her service on the Indian coast — a mock Tudor room with a mock log fire in an ingle-nook hung with horse brasses. What is more we were immediately greeted with large scotches and soda with ice. We hadn’t had anything like that for a long time. Later we learnt that our mess bills began again on the instant.

We were each allowed to send one short telegram home. I don’t remember what I put in mine and nobody appears to have kept it, but I know the address I sent it to — Hodges Place, Offham, Kent.

[page number: 116]