Summary

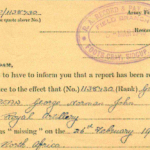

Geoff Harmer was captured in Libya at Bir El Gubi, after the tank he was hit and badly damaged. He was taken to Tripoli and then to a transit camp in Naples, before spending 18 months in permanent POW camps. In the Summer of 1943, he and his friend walked out of the front gate of the camp and headed South to Monte Falcone. After raiding a granary to help out a local Italian peasant, they were recaptured, taken to Ascoli Piceno, and then to a transit camp.

The full story follows, in two versions. The version in the first window below is the original scanned version of the story. In the second window below is the transcribed version in plain text.

[Digital page 1]

Geoff Harmer. (Taken from ‘When we were young’) 2nd Royal Gloucester Hussars.

Amusing about tank experiences just before capture including guiding the tanks with reins attached to drivers shoulders as radio down. First at Servigliano and then to Sforzacosta (?). When Order came to stay put he and another decided the easiest way was to walk out past the Italian guards who had no idea what was happening.

Got hidden up nr Monte Falcone (Opposite MSMS. K.K visited old couple who remembered him). After breaking into Gov. Grain store and helping to distribute to the needy got recaptured and taken to Ascoli Piceno. Max Schmeling (famous Ger. Boxer) tells them how well off they will be in Germany. A mixed bag of P.O.W.s organised a mass breakout. 8 were shot. Taken to Germany where GH ‘worked’ in Munchen, where they sell ‘Sun Kissed’ packets of tea – their own used leaves re-dried to population for bread. Sabotage work they are doing. Old sweats captured at Dunkirk had ‘canaries’ for sale – radios.

[Digital page 2]

FROM BIR EL GUBI BACK TO STROUD – WELL BLOODED

BY GEOFF HARMER

Bir El Gubi, the culmination of all our preparations, of necessity somewhat sketchy, for the testing times ahead.

Having been on a course I’d missed firing on the range and had no idea what it was like to be in the confined space of a turret when the 2 pounder fired. I knew the theory of course, the barrel recoiled towards my body and hopefully slowed down and was finally arrested by the oil buffer. I made a mental note to move to one side when we fired the first time just in case the thing was faulty!

Gubi was the first of the battles which for many would end in Italy and for some would be their last.

I’ve read somewhere that Churchill was anxious that our Yeomanry Tank Brigade should be “blooded” as soon as possible. As a journalist, Churchill had a well-deserved reputation for choosing the right word! Presumably, the top brass was wary of pitting these green territorials with their priceless new tanks against Rommel’s formidable Afrika Korps in their first action and so we were to deal first with the Italian Ariete Armoured Division, well dug in at Bir El Gubi and guarding the approaches to El Adem and the Tobruk perimeter.

It didn’t appear to be a very daunting task. Somebody told me that Intelligence was putting it about that the Italians didn’t have an anti tank gun capable of penetrating our Cruisers. Shooting up an enemy who couldn’t hit back seemed an appealing prospect! Having negotiated the wire at Fort Maddelena we duly arrived at El Gubi and the Italian front line, closed in and strained our eyes for likely targets. Then came my first sight of enemy tracer at first approaching deceptively slowly and then accelerating, and the realisation that the gunner had you in his sights. Oddly, when our tank was penetrated what with all the other noises of battle and talking on the inter-comm to the driver and gunner I wasn’t even aware of it! The first indication that something was wrong came when we had a misfire on the 2 pounder. Doug Drake who was loading eased open the breech, extracted the shell and tossed it out of the turret top. He loaded another and that didn’t fire. We were using the rack of shells beside the wireless set. I then witnessed the remarkable spectacle of Doug going through the rest, examining them and holding them to his ear, giving them a shake and jettisoning each one. “There’s an Italian shell stuck in among them. They’re damaged, loose in the case, that’s why they won’t fire” he explained. I thought “why the hell didn’t the whole lot go up, but thank God, anyway.” It had seemed for a moment that Doug was losing his marbles.

A quarter of a century later Doug and I were talking at a Squadron reunion about the size and weight of the No 9 wireless set. “They weren’t armour-plated though were they?” mused Doug.

[Digital Page 3]

I looked blank. “You remember the Italian shell that got mixed up with ours?” he continued.

“Of course.”

“You know how it got there?”

“I suppose it came through the turret on that corner.”

“No, it went through the wireless set first.”

I had my back against that set!

The enemy resistance began to crumble. We were in close enough to see the Bersaglieri still sporting those ridiculous cockerel feathers, climbing out of their trenches to surrender. I spotted one, either scared out of his wits or braver than the rest running away to fight another day. I got Tom Cook the gunner onto him and told him to fire. He knocked him over with a burst from the Besa. It was stupid, pointless, the poor devil wasn’t threatening us. Someone’s son, husband, father and I’d snuffed him out; something I shall always regret.

The battle petered out, so did the engine. When we got out it was clear why. Another shell had gone through the petrol tank into the engine and the fan had blown the leaking oil out at the back and the petrol hadn’t gone up! I ran over to Bill Trevor’s tank to report we weren’t going anywhere else that day. I felt I’d let him down. “Bad luck” he said. “we’re pushing on towards El Adem. You’re on the Regimental centre line – you’ll be picked up.” The Regiment moved off. We looked at our tank – what a mess!! In his book Stuart Pitman observes it sported four holes. He could have been right.

We soon had other things to occupy our attention. Presumably, in a classic all arms attack the infantry follow-up to round up the surrendered enemy but not here! The Italians, I imagine, couldn’t believe their luck and got back on their guns. Targets were in short supply. We certainly became one and the turret of a stationary tank which had proved extremely vulnerable to guns which I understood couldn’t damage us and which we couldn’t hit back at because we had no power, didn’t seem to be the best place to take cover. We dived into the nearest trench and let the storm whizz over our heads. For some reason the enemy didn’t send out an infantry section to winkle us out. Luckily, help was at hand. Another of our tanks commanded by Jock Anderson was not far away with a damaged track. They’d managed to get going, it circled round our trench, Jock jumped out and dived in on top of us. “I’ve left Jack White in command” he said. “I told him to keep moving to lessen the chances of being hit again and the next time he comes round get up and make a run for it.” The tank came clattering by and we began to chase it. Jack had been told to keep on the move. Stumbling through the sand it was obvious we were losing ground. The air was full of strange Scottish oaths as Jock bawled at Jack to stop the thing and let us get aboard. The absurdity of the situation suddenly hit me. I laughed so much I could no longer run. When we finally managed to climb on there was Jack in the turret placidly smoking that foul pipe. We drove back along our line of advance until we bumped into rear echelon where everybody was anxious to hear how the action had gone. I had to confess we’d lost the tank which was bad enough. What concerned the crew most was the loss of our store of

[Digital Page 4]

pineapple chunks and condensed milk! Anticipating rations up the blue would be monotonous we’ d spent all our available cash on tins, enough to stuff the sub-turret. We were still with the echelon when the rear areas were overrun by Rommel’s ill-planned dash to the wire. The driver of our truck, in common with everybody else, was going at such a lick to escape the approaching German tanks that something broke and we bailed out. I found myself in the ludicrous position of standing in the desert literally thumbing a lift at what appeared to be every soft-skinned vehicle in the 8th Army streaming past. Nobody stopped. I felt my luck had changed when I saw “G” Squadron fitters approaching in their 15 cwt. “Sorry, we’re already overloaded” apologised Pop Allies. “But there are plenty of our trucks just behind.” True enough I soon got a lift. As 8th Army sorted itself out Arthur Mitchell began to comb the trucks for a crew, having found himself another tank. I acted as his gunner until the Regiment was pulled back to re-equip with Honey tanks. On Lieut Mitchell’s departure I was ordered to take over the tank and we joined another outfit. I. never did find out who we were with! I did find one great difference. With the R.G.H. [Royal Gloucester Hussars] there was never any doubt that we were going to see some action (often too much). During the time I spent with this other unit I can’t recall an occasion when we were fired on or we attacked anyone. To be fair, the object of the operation may have been to conserve tanks. The Regiment, having received its complement of Honeys, we were collected to crew one and I reported to Bill Trevor. “That’s yours. It’s the only one left” he said, indicating one which looked even more clapped out than the rest. The wireless didn’t work so of course I couldn’t talk to the gunner or the driver. Having to duck into the turret to give the gunner Bill Booy a fire order presented a problem, but not a major one. But directing the driver Algie Pool was going to prove more difficult. The only idea we could come up with was to tie a couple of pieces of string to his epaulettes. A pull to go left or right, a flap on the reins to proceed or speed up and reining back with both hands to slow down or stop. It worked reasonably well when we were facing the same way, not so good when the turret revolved and Algie didn’t revolve with it!

A couple of days later we were ordered to do an offensive sweep along the edge of a strong anti-tank position the Germans held in rocky ground. Many years later I gathered this became known in the annals of the Regiment as “Shit Creek.” Those there will appreciate why. It was immediately clear that subject to heavy anti-tank fire at close range from guns so well concealed in the rocks that I couldn’t spot one we were on a hiding to nothing. I spotted Harold Carr and Bob Hughes in the tank next to mine crouching behind it trying to find some protection. Presumably Bill Trevor gave the order to withdraw. If so, I didn’t know because of the lack of a wireless set. The first I knew of it was the sight of such tanks as were still goers disappearing back the way we had come. A flap on the reins got Algie going. A yank on one epaulette got us turning to circle round and follow the others. Pulling the other bit of string to straighten up met with no response. An agonised face with streaming eyes looked back from the driver’s compartment. “We can only steer on one tiller. The other side must have been hit” announced Algie.

[Digital Page 5]

[Handwritten Note at Top of Page]: Monturano or Sforzacosta

“And things are getting hot down here. Something’s burning and I can’t breathe.” That had to be it. Running round in circles in front of anti-tank guns in a tank which was beginning to smoulder didn’t seem to offer any great prospects. I bawled “Bail out” and went out of the top followed by Bill and Johnny Randall. Algie made his own arrangements but I must confess I’d forgotten the string. I started to run the way the tanks had gone. Instinctively, but completely useless. There was no way we would get away on foot. The enemy machine gunners saw to that and opened up. I dived into the sand facing upslope. Until that moment I’d been terrified. What happened then was something I’ve never been able to understand. I no longer felt afraid. Knowing I only had seconds to live I accepted it. It would be painless and my only feeling was that this was a lousy way to go. I’d read somewhere that a drowning man sees his whole life flash before him. It’s true. It happened to me. The firing stopped and I remember thinking that perhaps I might get away with it after all. I looked up at the sun trying to calculate how long before it was dark providing the Germans didn’t bother to pick us up at once. Completely stupid of course. I saw a section of German infantry coming towards us from the rocks. Bill Booy’s disembodied voice came from a patch of scrub. “What are you going to do?”

“Turn it in” I shouted. I stood and raised my arms. The first German trotted up to me and began to search my pockets. He looked a little more than a boy. His hands were shaking so much he couldn’t unbutton my shirt pocket. I lowered my arms to do it for him. He took my case containing my last cigarette and so we went into captivity.

We were taken by truck to Derna and the P.O.W. cage in Benghazi. Then by cargo boat to Tripoli and in coal trucks south into the desert to the foot of a mountain with a little town perched on top, Jebel Gareon.

Back to Tripoli and across the Mediterranean to Naples and a transit camp. Then eighteen months in permanent camps until a day in the summer of 1943 when the senior British Officer announced that the Allied Armies had landed in southern Italy and the Italians had been granted an Armistice. He went on to say that “our new friends and Allies, the Italians” had assured him that there were no Germans near the camp and if any approached they would tell him and he would march us out. In the meantime, “carry on as usual.”

Having seen in the desert how completely the Italians were under the German jackboot my mate Charlie and I were doubtful about the Italians doing anything of the sort. Obviously other people felt the same way and it wasn’t long before the camp leader was on the air again to say it had come to his notice that prisoners were talking about trying to escape. This was contrary to his orders and if anyone tried to do so they would be court martialled after the war. To us, the possibility of a court martial seemed preferable to being shipped into Germany, which we were sure would happen if we stayed where we were. We decided we’d try to get away. The problem was how. The wire was still manned by armed guards, which didn’t seem a very friendly act on the part

[Digital Page 6]

of our “New friends and Allies.” We could hardly expect them to stand by as interested spectators as we went over, under or through the wire. That pointed us to the only other way out – through the front door. The gate was locked and manned by a couple of sentries who unlocked it to allow guards and carts into the P.O.W. compound. We could hardly ask them to unlock the gate to allow us to escape. Even the Italians wouldn’t fall for that one. We’d have to hang about near the gate until it was unlocked and walk out then. We had a feeling that the sentries probably didn’t know any more about what was going on than we did. It was doubtful if they even knew which side they were on. Suppose we presented them with a situation they’d never experienced. 2 prisoners walking out as if they’d had a right to do so?! The weakness of the guards’ situation was that they were divorced from the guard commander in the Italian part of the complex. If they didn’t know what to do there was no-one to ask and while they were sorting it out, with luck we’d be gone. Obviously one of three things could happen. They could point a gun at us and tell us to go back, which we accepted we would have to do; they could shoot us on sight and we dismissed that as being out of the question, or, not knowing what to do, they would do nothing. We waited near the gate until the ration cart came down the lane. The sentries unlocked the gate. In came the cart. We went out, wished the guards a polite “Buona Serra” and began to walk away. At any moment I expected to hear a shout or a warning shot. I remember thinking “don’t look round and whatever you do don’t run.” Nothing happened. We spotted a gate on the left leading to an orchard, went through it and we were out of sight of the camp, the wire, the sentries. We’d done it! Free! As easy as that.

We started to climb up into the mountains and spent the night sleeping with the cow in a shed. Next morning we took stock. Didn’t know where we were. Perhaps a third of the way down from the top somewhere in the eastern foothills of the Appenines. Our sense of geography was so bad we had no idea where we’d finish up if we went north. Unoccupied France? Switzerland? Austria? In the absence of any better idea we decided to march south “towards the sound of the guns.” We had a vague idea that one day we might creep through the German lines into our own and if that wasn’t possible get as near the front as we could, go to earth when the Allies advanced, let the war roll over us and pop up again the right side.

For the rest of the summer and most of the winter we wandered down south, always keeping to the mountains, away from roads, scrounging a meal here and there and somewhere to sleep. Always warmly received by the Contadini, the peasants who hated Mussolini and the Fascists who’d led them into a disastrous war. The Germans plastered the mountains with posters offering rewards to anyone capturing or giving information leading to the capture of escaped prisoners. They attracted bounty hunters armed with knives and clubs and sometimes guns. We were lucky and were never troubled. I later met up with one chap who’d got away from my camp. He’d been jumped on one night and had both legs badly shot up. A fine athlete, he was now crippled for life. The posters even offered rewards for information about Italians who

[Digital Page 7]

had helped prisoners. If any of those countless Italians who befriended us ever saw one of those posters they certainly weren’t lured by the rewards. During the winter the peasants began to run short of flour, having had part of their harvest confiscated. They told us that parties of armed men, royalists, anti-fascists, communists, strange bedfellows, were going through the mountains “liberating” this grain from government storehouses and handing it back to the peasants. One of these granaries was in the little town of Monte Falcone, near where we were staying and these partisans were expected to “do their stuff” there within a week. We asked them to tell us when it was going to happen and we would help. A week passed and no news.

One of the other escapees in the district suggested we should do the job ourselves as the Italians obviously weren’t coming. If I’d had more sense I should have said “hang about, if we get away with this we’ll be hunted through the mountains and the peasants will be afraid to give us food and shelter.” Not wishing to be found lacking, I said nothing. Four or five of us assembled after dark. One brought an axe to batter in the door of the grain-store. I wasn’t happy when another arrived with a shotgun. Store-breaking and larceny was one thing, shooting at Italians was another, especially with this thing, one degree from a muzzle loading blunderbuss literally held together with wire and nails. He generously offered it to each of us. Having inspected this lethal monster we politely declined and climbed the mountain to Monte Falcone. We knew the town well having been to the cinema and a wedding there and found the grain store. The chap with the axe started to batter in the door. Unknown to us then, but as I discovered later, the house opposite was occupied by the town mayor who, as the local custodian of government property, presumably felt he should make some token defence of it.

Suddenly we heard what sounded like a point 22 Rook rifle being fired. Standing within a stout stone porch we were in no danger but the firing eventually annoyed the bloke with the shotgun to such an extent that he shoved it round the corner of the porch in the general direction of the town mayor’s house and pulled the trigger. I don’t suppose he did any damage but it kept the town mayor quiet for the rest of the night! The door went in with a crash. We went inside, filled our sacks with grain and retreated down the mountain. “The place is open. It’s your grain. Go and get it” we told the Italians. All night they were up and down the mountain with their cow-carts and cleaned the place out. Next day we were hanging around the house congratulating ourselves on a job well done when Pacifico in whose house we were living rushed in shouting “The fascists are coming. You must go.” Naturally, we needed no second bidding and went to ground in the mountains and crept back at night to discover it had been a false alarm. Next day the same thing happened but instead of having the sense to make ourselves scarce we wandered up the street and chatted with a couple of Americans about this second scare. Suddenly, around the corner appeared a chap in plain clothes sporting a machine pistol and a revolver and a uniformed policeman with a carbine which he immediately put to his shoulder and fired a shot over our heads, warning us to stand still. It had the opposite effect and we began to run. I knew at once I

[Digital Page 8]

was going the wrong way, trying to run over wet plough-land

wearing home-made wooden soles held on with bits of bicycle tyre I wasn’t

making much progress. I climbed over the wall and popped my head over the top

to see what was happening. The plain-clothes chap, pistol in hand, was right on

top of us. I raised my arms to show I wasn’t running any further but whether by

design or accident I knew not, he pulled the trigger. Thank God he missed.

“I’m looking for the men who broke into the grain store” he said.

“Sorry, I wouldn’t know anything about that” I replied. “If that’s

all it is. I’ll be off.” A wave of the pistol stopped me.

“I wasn’t looking for you – but I know who you are, and now I’ve got you

I’m arresting you” he said. He marched us back to the village and demanded

transport to take us up the mountain to Monte Falcone where he’d left his car.

All the Italians could come up with was one of the ubiquitous cow carts.

Charlie and I felt ridiculous standing in the wretched thing like a couple of

French aristocrats being driven off in a tumbrel to the guillotine, especially

as the whole village, including the girls we’d been laying siege to all those

months, had assembled to see us off. In Monte Falcone we transferred to his car

to be driven to the next town which boasted a police station. A long time later

I discovered we’d been lucky, anti-fascists were laying for this particular

plain-clothes policeman that day but waiting on the wrong road. Next time he

came into the area they were in the right place and, recognising his car,

riddled it as he went by. He handed us over to the station sergeant and the

other policeman and disappeared. The police cooked us some sausages, we drank

some wine and they suggested a hand of cards. We knew nothing about the suits,

of course, cudgels, goblets, angels and something else. Charlie and I played

partnership Whist. I don’t know what the Italians were playing but it certainly

wasn’t Whist. By common consent each side claimed a trick whenever it seemed

appropriate. “I shall have to lock you up for the night” apologised

the Sergeant. He took us along a passage, unlocked the cell door and switched

on the light. A chorus of snores emerged from the pile of blankets on a

circular bench. “Wake up” shouted the sergeant. A half dozen sleepy

Italians emerged from the blankets. “The Englishmen will have the beds –

the Italians will stand up in the passage” announced the Sergeant. Charlie

and I got our heads down. Clearly, we were an embarrassment in this little

police station and the Italians were quickly in touch with the German Army. Next

day we were taken outside where there was an open truck manned by a crew of

three, two Germans and a young Italian acting as interpreter. This was

obviously a quarter-master’s foraging party as the truck was half full of pigs.

Accompanied by our police escort we joined the pigs and were in turn joined by

various Italians cadging a lift. They included an Italian Warrant Officer with

a machine pistol which he tapped ominously to show what he intended to do if we

jumped out. He sat facing forward with his back to the pigs up against the

tail-board. The rest of us faced him with our backs to the cab. The order of

seating was nearly to prove fatal. From time to time as one of the pigs

trespassed on what he considered to be his bit of floor space, he would jab

backwards with the butt of the machine pistol at the offending pig, muzzle

towards the rest

[Digital Page 9]

of us. The idiot. The gun was not only loaded, it was cocked. The next time he did it the gun fired. How he missed us I don’t know. I thought afterwards it was fortunate the gun with the safety catch either off or faulty was on single shot. Had it been on automatic he could have slaughtered the lot of us. The Italians dropped off and we went on. Climbing an icy pass the inevitable happened, the truck slid off the road into a snowdrift and refused to budge. The Germans announced we would have to spend the night there and they, and the Italian policeman would take it in turns to mount guard. Wearing greatcoats, balaclavas and gloves they were all right. Charlie and I weren’t equipped to spend a summer’s evening out of doors and it was freezing. It wasn’t long before I decided if I wasn’t stiff by the morning I’d be down with hypothermia or pneumonia, I suddenly realised I was neglecting an important source of heat, the pigs were heaped up into a mound. We wedged ourselves in the corners with our backs up against this ton of pig meat which gave off enough warmth to stop us from freezing.

Next morning the Germans despatched the interpreter to find help and he returned with some peasants and their cows to tow us out. We eventually arrived at Ascoli Piceno which boasted a civilian jail. The policeman invited us to a farewell drink and we killed a bottle in a wine shop. In the jail we joined a dozen or so recaptured escapees and one British paratrooper who had jumped in the wrong place. Our next move was to a temporary transit camp where I bumped into a chap I’d known in my last P.O.W camp. “I’ve just been brought in and I’m on my way out again” he confided. He was small, dark and wearing genuine Italian workman’s clothes, indistinguishable from the Italians putting the finishing touches to the P.O.W compound. He’d noticed that when workmen left the compound they didn’t show a pass and there didn’t appear to be a password. “Chat up the sentry on the gate. I’ll be along in a minute, but don’t pay any attention to me” he said. I kept the sentry occupied and out of the corner of my eye saw my friend approaching. He’d picked up a plank of wood and walked confidently up to the gate. The sentry never gave him a glance, unlocked the gate and out he went and around the corner with his plank. I never saw him again.

There was an interesting diversion one day when a large black Mercedes swung into the compound and out stepped a huge man followed by an attractive blonde. He signalled us to gather round and introduced himself. Max Schmeling, the German heavyweight who twice fought Joe Louis. He was on propaganda work for the Germans, promising sports equipment when we reached Germany. Those lucky enough to be at the front smoked his cigarettes and the rest of us ogled the blonde. Things were going well until one wag at the back bawled, “What price Joe Louis?” Max disappeared into the car. So did the cigarettes and the blonde’s legs. A pity!

This camp was the scene of an attempted mass break-out in which I took no part and which ended fatally. The compound was enclosed by two barbed wire fences on flimsy poles and the plan was for everyone to yank at those fences and they would come down. Some of us had grave reservations. Included among the prisoners were

[Digital Page 10]

various men we couldn’t place. Some spoke no English and said they were “Russki.” Others, who had little English but clearly understood German, claimed to be Dutch-speaking Boers from South Africa. Several small incidents made us suspicious that there was little going on in the P.O.W compound the Germans didn’t know about and that one or more of these men were plants. There appeared to be more guards than usual along that side of the fence chosen for the break-out. Nevertheless many chaps decided to give it a go. A crowd rushed this first fence, pulled, and down it came. They were over the first fence and heading for the second. Then the Germans appeared in force, firing over their heads to drive them back. Many realised the game was up and ran back, others pressed on but there were no longer enough to pull down the next fence. The guards continued to fire high. Almost all of those remaining gave up, except a few very brave but foolish spirits who started to climb the wire. Despite repeated warnings from the guards they pressed on until the Germans had no option but to fire at them; eight men were killed.

It was while I was in this camp that I ran into John Saleby who, after we’d shaken hands, observed that I wasn’t wearing chevrons and offered to cut a piece off his shirt for me to fashion the missing stripes. As I’d spent many months trying to pass myself off as an Italian I politely declined. John, who was hoping to make another escape, had bartered something for one of those one- piece American combat suits, admirable for sleeping out. Unfortunately John, six feet plus, had done a deal with the shortest American in the U.S Army. It fitted him like a glove and he confessed to being in some difficulty when answering the call of nature. That diagonal slit on the crotch didn’t fall in exactly the right place!

The Officers were soon shipped out to Germany and soon after that the Germans announced that all the British would go the following day. Hoping that if I could manage to stay in Italy I might be rescued when the Allies advanced, I decided I wasn’t going and when my name was called I went to earth. I was the only one of the British left in a camp of Americans and other odd bods. It was a dreadful place with little food and no blankets. Time passed and after a while I realised that my health was deteriorating so quickly that I must get to a permanent camp. I was in luck. The Germans announced that the Americans would be shipped into Germany. One of the Americans in my squad felt too ill to travel. He agreed that I should take his place. When Private First Class Owen was called I answered and got aboard one of the trucks which would take us on the first part of our journey north. We were relieved to find that at least part of the journey would be by road, an earlier shipment was locked in goods vans standing in a siding while the engine got up steam. An R.A.F recce plane came over, spotted two other trains, one loaded with ammunition and a second with petrol in the same sidings, and disappeared. Everyone knew what was going to happen. Over came the bombers and up went the ammunition and petrol, and a lot of P.O.W.s. We travelled to a town somewhere south of the Brenner Pass where we were put into a temporary camp and told we would go through the Pass by train next day.

[Digital Page 11]

This camp presented the ideal opportunity for a quick tunnel job. The wire fence was only a yard or two from the wall of the warehouse in which we were held. The sentry patrolled between the two. A tunnel, started by the interior wall, needed only a couple of yards to see us the right side of the wire. Led by an American Ranger we started to dig, knowing we had only one night to complete the job.

Unfortunately, we lost our way in a maze of foundations and rock. With a couple of hours to daylight we decided to come up and see where we were. The American cautiously broke through the surface only to find we were still the wrong side of the wire!

Our tunnel emerged right under the sentry’s boots. We knew the game was up. At first light the sentry spotted a small hole as he marched up and down. The alarm was raised. The German Camp Commander led the guard into the warehouse, spotted our tunnel, had a good laugh and remarked it was a good job we were there for only one night.

The thing I remember most about the train journey through the Pass was the toilet arrangements. Each van contained a wooden box. Porous. In no time the thing was leaking like a sieve and the van was awash.

When we were climbing, which was most of the time, the tide came in at the back of the van. Those lying there were praying for the train to go downhill, reverse the flow and take the smiles off the faces of those up the front. Unpleasant, but at least it was rare for the R.A.F to bomb that far north, which was worth something.

I spent most of the rest of the war in a permanent camp near Munich. Occasionally we had the opportunity to spend a day there on a working party. The Germans, always correct in these matters, never forced N.C.O.’s [Non-Commissioned Officers] to work but insisted that one N.C.O should accompany each working party of 25.

There was always great competition to get on one of these parties which “repaired” bomb damage in Munich. We were able to get involved in the black market. The Germans had bread, we had tea from Red Cross parcels.

Our method of brewing was never to throw away the tea leaves but add one spoonful each time. Eventually, one reached the stage where there was no room for water because the pot was full of leaves. The leaves were tipped out, dried in the sun and carefully sealed in the packet. This particular brand was known in the trade as “Sun-Kissed Tea.”

Armed with your packets of Sun-Kissed you went off to Munich with your working party. Before long you were likely to be approached at the railway station by a child who said “My mummy would like the black tea (the original article and rarely on offer) if you have it, but she says if you haven’t the white tea (Sun-Kissed) will do.” A packet of Sun-Kissed was solemnly exchanged for two loaves. Meanwhile, the working party was “repairing” bomb

[Digital Page 12]

damage. The guard would tell you to get two or three of your men onto the station master’s roof where a few slates had been blown off. It never failed to astonish me how a trio of soldiers wearing Army boots could inflict such damage on a slate roof if they were careless. By the time it came to leave they had crashed through most of the roof.

“Afraid there was more damage than we at first thought. We had to remove a lot of tiles which can be replaced tomorrow” you explained.

The loss of the Station Master’s roof was nothing as compared to the results achieved in relaying the line. Care was taken to include a number of Sappers in each working party. By judicious use of stout timbers to take the weight of the sleepers and lengths of line, camouflaged by a generous application of ballast, it was possible to disguise the fact that the rails were resting on little more than air.

As the first train steamed slowly through, sleepers and the engines front wheels broke through the crust and disappeared. “Sorry about that, but our chaps aren’t engineers, they’re doing their best” the Germans were told.

As the war neared its end I was moved to another camp where there were a number of men who had been taken prisoner at Dunkirk. The real old sweats of P.O.W.s who had succeeded in adapting the Germans to P.O.W life rather than the other way round.

Wandering through their huts one day I spotted a notice, “Canary for Sale.” It didn’t surprise me that somebody wanted to keep a pet, most things were available from the guards at a price, but quickly I discovered that things weren’t always what they appeared. Further on was another notice, “Canary for Sale, 1 Ear.” Who on earth would keep a Canary with one ear, and how had the bird lost it? But, “Canary for Sale in Pieces” was too much.

“What’s this Canary business?” I asked.

“It’s a wireless set” explained one of the old timers. “One ear

means it only has one earphone. In pieces is just what it says.” Simple,

but how did they get the batteries charged? Through the guards, of course.

Expensive, surely? “Not really” he explained, “you only pay him

the first time. After that, if he refuses, we threaten to tell the duty officer

what he’s been doing. It always works.”

As the Russians closed in from the east and the Americans from the west much to our relief the Germans not wishing to be overrun by the Russians got us on the road marching westwards. On the first night, smitten with some stomach bug which necessitated my falling out to crouch by the side of the road every ten minutes, I watched the column disappear. I plodded after them, praying the road didn’t fork as I would have no idea which way to go.

[Digital Page 13]

I found the column lying up in barns at a farm. This proved to be the end of the march. Presumably the Germans knew this area was on the line of the American advance and were resigned to staying there until they arrived.

Within a couple of days someone spotted an American infantry patrol coming down the road. Our captors were taken into the bag and soon after, American trucks arrived to drive us to an airfield and we were flown into France. The R.A.F flew us home.

We were given leave and returned to a resettlement camp. All escapees were assembled and addressed by an Officer who told us “The Army realises that you chaps who escaped must have sold personal items of value to keep body and soul together. The Army doesn’t want you to suffer personal loss. Make a list of all the items you’ve had to sell.” Suddenly, everybody recalled what they had sold. The claims were endless. It was incredible what they possessed when they escaped. Rings, watches, cigarette cases, fountain pens, propelling pencils, lucky charm bracelets.

Chaps were sitting there, steam visibly rising from the tops of their heads as they sucked on pencils, wondering whether their list would stand one more gold ring, and the Army paid up. Nothing was challenged!!!

But the Army was wary about escapees who might attempt to claim an Army pension on the grounds that their physical or mental health had been impaired by their years of captivity. Nobody was going to be discharged until the Army was satisfied that they were fit.

The physical test involved running 100 yards and a mile, and walking five miles in specified times. Any of you were going to stay there practising until you could do it. The prospect of doing it more than once acted as a tremendous spur. I passed first time.

The moment I saw the preparations for the sanity test I knew I would fail. Each of us was seated at a table on which was displayed ten items, in pieces. They had to be re-assembled. I’ve always suffered from a mental block where practical things are concerned. Seven out of ten, including the bits and pieces of a lock I immediately pushed to one side as being quite beyond me. That left me with the links of a chandelier chain, a plank of wood representing a door to which a handle had to be screwed and the innards of a bicycle pump. The chandelier chain presented no problem. I got the door handle screwed on and the bits of the pump back inside. The Army psychiatrist bloke with his clipboard cast an eye over my offering. One mark for the chandelier chain, only half a mark for the door handle, which was securely screwed but pointing the wrong way and half a mark for the bicycle pump – – – “you’ve got nothing left over and it might conceivably suck air but it certainly wouldn’t blow. 2 out of 10. According to the Army you’re insane.” I hastened to explain that I wasn’t trying to work my ticket or claim a pension, it was just that I couldn’t have reassembled all these things even before I was a P.O.W. He seemed to believe me and I

[Digital Page 14]

was declared fit and posted to a Recce Regiment at Devizes. Nobody seemed to know what to do with us at this training Regiment. They’d spent the war training blokes so they carried on putting us through the routines they knew. Arms instruction. We practised throwing dummy hand grenades, thank God they were dummies because mine always landed a few yards away. Then the Bren gun. A young instructor explained the working of the Bren gun. “This gun weighs X pounds. It’s gas-operated and is fed from a magazine on the top holding 28 rounds” . . . and so on! It wasn’t long before one leathery old sergeant got to his feet. “Son, I was killing Germans with one of these at Dunkirk while you were at school. Show me once more how to load it and I’ll wrap it round your neck.”

The brass finally appreciated this really wasn’t the best way to prepare us for civilian life. They announced a series of educational visits to places like Harris’s bacon factory at Calne and the brewery in Devizes which meant spending most of the morning in the pub.

I came away from the training Regiment with only one useful acquisition – a driving licence! As the Driving Test Centres couldn’t hope to cope with the vast numbers of men who had learned to drive in the Army but did not hold civilian driving licences, the Transport Officers were given the authority to issue certificates guaranteeing competence to drive on presentation of which a civilian licence would be issued!

I reported to the Transport Officer. A 15 cwt was parked on the square. I drove round once in second gear. “A bit rusty but you’re all right” he said, handing me my certificate. And so to demobilisation, back to Stroud to meet up with some of the Squadron I hadn’t seen since 1941 and those fearsome morning binges in “The Railway Hotel”, a kip in the afternoon and another trip to “The Railway” at night.

Things soon got back to normal, except for the sight of Italian prisoners escorting girls to the cinema. I never did understand that!